Art helps us see things more clearly

An interview with Greek art collector Irene Panagopoulos

As I spoke to Greek collector and entrepreneur Irene Panagopoulos in her office in Athens, I thought to myself that her slightly hushed voice suits the space so well - it symbiotically meshes with the artworks all around as well as with the fragile space of silence they inhabit. Every word she says encourages one to lean in and listen, just like works of art do - to notice, to look deeper, and to see.

Panagopoulos is the CEO of Magna Marine Inc., a dry bulk shipping company founded by her father, Pericles Panagopoulos, who was also a collector. Art collecting is in Irene’s genes and, as we will touch upon later, in the genes of Greeks in general. Irene’s contemporaries and fellow Greeks, Dakis Joannou and Dimitris Daskalopoulos, are among the most internationally known, influential - and generous - collectors of contemporary art.

Works from her father's collection, which included among others oriental rugs, antique maps, and works by Greek artists from the 1970s and 1980s, were to form the basis of Irene’s collection - a seedling that has continued to grow and develop naturally, step by step, as it has acquired its own unique identity.

Hatoum Mona: Baluchi (red and blue), 2012, wool, 125 x 190 cm. “A familiar object of home, engraved with a world map.”

Before becoming the head of the company Irene Panagopoulos initially studied art and photography. Her alma mater was Mills College in the USA, and her teachers included well-known artists such as Jay DeFeo, Katherine Wagner, Ron Nagle and John Roloff. She learned the essentials of becoming an artist and what the process of making art is all about. She did not become an artist herself but instead became a collector and patron of the arts, supporting artists, the art ecosystem, and the art-making process as a whole.

Irene Panagopoulos lives in Greece. She is a collector of modern and contemporary art with an emphasis on Eastern Mediterranean and book arts. As patron, she supports art organizations and cultural events in Greece and abroad. She is Trustee of the following institutions: Dia Art Foundation (USA), Delfina Foundation (Great Britain), National Gallery of Greece (Greece). She is member or the International Council of Tate.

The way Panagopoulos talks about art combines emotionality and rationality. She has the sensitivity of an artist and a very sharp, strong mind. There are many works by women in her collection. As Irene will later admit in our conversation, this was not a conscious goal of hers - these are women of mostly her generation who address subjects that are important to her as well: women's rights, relationships, equality, social issues.

Hatoum Mona: Natura morta (medical cabinet), 2012, Murano mirrored glass, steel and glass cabinet, 261 x 54 x 17 cm. “Mona Hatoum, a Palestinian artist, has been exploring themes of displacement, conflict and home. In this work, a familiar domestic cabinet is filled with “hand grenades” made of Murano glass.”

If we look at ancient cave paintings, art appears to be one of the first things humans created. What does art mean to us as humans?

Art reminds us of our relationships, our identity, who we are, what we represent, and where we want to be. It highlights our connections and serves as a tool for communication. We need art because it reminds us of beauty and helps us see things more clearly. I believe that art is like a voice. And as a voice, it is often more powerful than words. It can also tell us who we are. It underscores that we are human above all. My "aha" moments often come through art.

In language we are limited, but art provides another dimension through which we can communicate beyond words.

So for that matter, I support museums and artist residencies. Supporting those who help artists be creative is important to me in my patronage. I am artist-centric; I have supported biennials and museum shows.

Dia Art Foundation, where I am a trustee, is committed to advancing, realizing, and preserving the vision of artists, by collecting and commissioning new site specific works. Dia is the owner of major projects some of which are sited outside the museum or gallery. Besides the exhibition spaces in New York, there are additional nine permanent sites across the United States and Germany. These projects, all open to the public, continue to be maintained by Dia today.

With the International Council of Tate we fund acquisitions of works by artists from around the world. To make those selections, we travel to visit artists in their studios, visit museums and meet local collectors, always accompanied by the knowledgeable directors, curators and staff of the Tate, in order to make the right selections for the museum’s collection.

Artist residencies are communities where artists can stay and nurture their creativity. I was always intrigued by such artist spaces, so for a long time I supported Delfina Foundation, where I became a trustee. It is the UK’s largest international artist residency, with a history of nearly 40 years. Delfina has been an intimate home for artists and is currently campaigning to raise necessary funds to acquire their building in order to secure the future of their mission.

You collect artist books so, what was it about artist books that you found so interesting and fascinating?

As a collector, I am drawn to dimension. I like sculpture, and photography intrigues me because, even though it's flat, it still conveys a sense of dimension. Artist books add another layer of dimension because as you turn the pages, each page adds a new emotion. For me, a book is multidimensional. I have always been fascinated by books as art form. My first collection was artist books - books made by artists. You can still find unique artist books.

I’m not sure how artist books are perceived today with the rise of paperless technology, but for me, turning a page is not unlike scrolling through media. Modern media often encourages us to move quickly from one image to the next, but books offer a continuous, immersive experience. Each page in an artist book reveals something new, making it a continuous work of art. There is a sense of motion and kinetic quality in a book that I find captivating.

Do you still follow along with what is happening in the field of artist books?

The section of artist books is almost disappearing. You don't see very much at art fairs. There are printers who are dedicated to creating artistic books such as Three Star Books in Paris, Crown Point Press and there are specialized fairs for books. I have visited private collections dedicated to artist books and there are libraries with well known collections, such as the Morgan Library in New York.

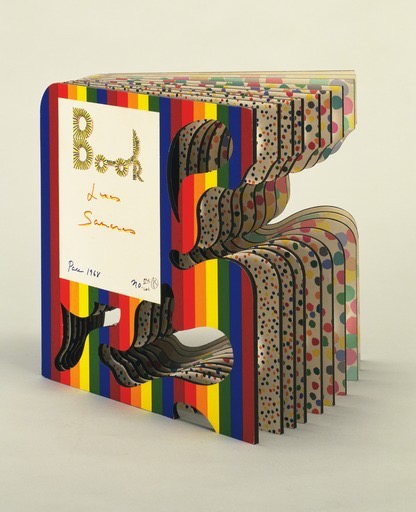

Samaras Lucas (1936 - 2024): Book, 1968, thermographically die cut illustrated book. “One of my favorite colorful artist books, by Lucas Samaras.”

For me, it was interesting to read about your father's approach to art. In one interview, you mentioned that for him, it was like an aesthetic retreat. Somehow, you inherited his love for art and it has been passed on to your children as well, as I understand.

My father was a connoisseur collector. In everything he did, he wanted to ensure quality and originality. In all of his projects, he included original art. He personally visited artist studios and galleries, and in the style of his own home, he always integrated art into his workspaces as well. By the way he also loved traditional handicrafts. In addition, he combined designer furniture and collaborated with architects and designers to complete his projects.

Additionally, he gave me some works of art from his collection. While he was still alive, he said, “Take these paintings and see how they relate to you.” After sometime, I thought I could add to this group their “brothers and sisters” from the same community of mostly Greek artists.

At some point I thought maybe these works had “cousins and relations” in the Greek diaspora, as we are a nation of emigrants. I started looking at artists of the same generation who had left the country. In the process, I came across other artists who may have been friends or influences. The puzzle grew, and my collection expanded. Now it's very international but always focused on where I live - Greece and the southeastern Mediterranean. I also include Italy because my mother was Italian, and the Balkans, as we can now communicate with our Balkan neighbors since the borders have opened. We are discovering how much more we have in common and how these artists integrate. I am interested in the dialogues and the connections in an art collection.

It sounds like through art you are, in a way, discovering your roots as a human?

My roots are complicated, like our part of the world. Our history has been turbulent with invasions and occupations since ancient Greece, Roman times, Byzantine era, then Ottoman and back to Greece. Who are we? I think artists have the best way to expand our vision and to open our minds.

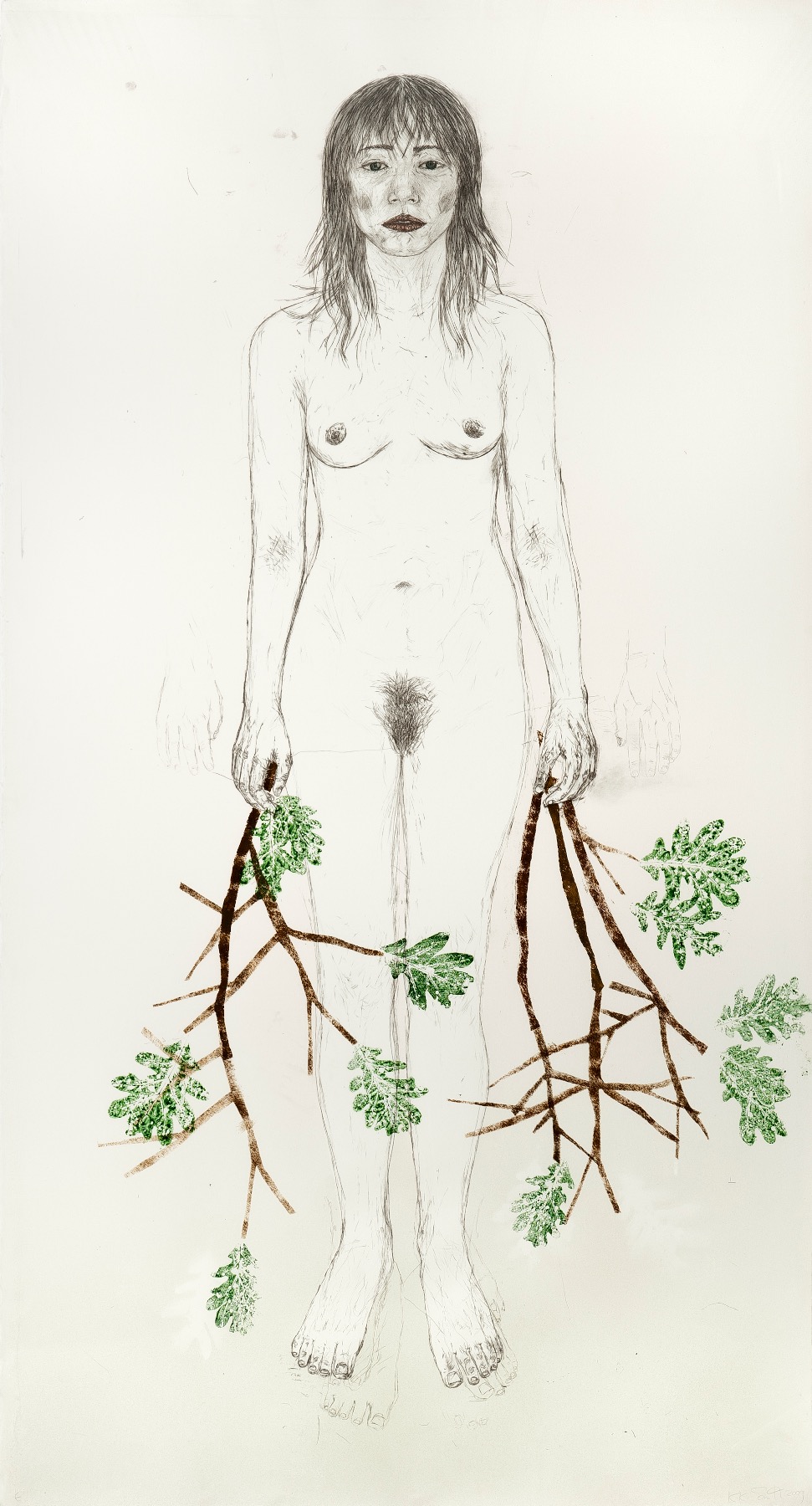

Smith Kiki (b. 1954): Untitled, 2009, lithography, 199 x 110 cm. “An image of a naked woman holding tree branches, facing down instead of upwards. They look almost like roots.”

You studied art yourself, but you did not become an artist or even a curator or gallerist.

I did not become an artist, which is okay. Life had another plan for me. I still think like an artist, and when I see an artist’s work, I am looking for the questions and ideas that still float in my mind. So I am excited when I see work that I feel best expresses those thoughts. Generally in my mind I think about various issues such as my identity and my nationality. However, I also think about colors and shapes and type, and I love words and type, which may explain my love of books.

I am happy being a collector. I don’t know what kind of artist I would make; maybe it’s better that I am a collector. But I definitely have an artistic mind.

Did you ever ask yourself, "What is an artist?" Is being an artist a profession, or is it something else?

I’ve never really thought about that before. Actually, it’s a very good question. You can make a living from art, but not always. Like in any field, some artists earn more than others. This is true in every profession.

I believe that if you are an artist, you have to pursue it. It’s going to be challenging, but you must keep striving. Being an artist is probably a deep-rooted need, a drive to express yourself freely. Many artists end up doing other jobs to support themselves, which might be why I didn’t become an artist. Many artists take on various roles, such as teaching, to make a living. This can sometimes hinder their ability to focus on their art.

This is why support is so important - it helps to make it possible for artists to create. Is being an artist a profession? I dislike the word “profession” because it implies something you don’t always enjoy.

This brings the aspect of patronage into focus and highlights why it was so important for centuries. In our current world, which is highly unstable and unpredictable, patronage is even more crucial. What do you think is the role of patronage today?

If I were advising an artist, I would say: Focus on creating your art and apply for funding to support it. There are various methods available. Many residencies around the world are willing to provide studio space, housing, and even financial support. Additionally, there are grants available, so explore those opportunities. My advice is to concentrate on making art as much as possible.

An artist is a special person who needs support to be able to create art. New spaces and new projects, in Athens, are focusing on emerging artists. There is a growing and nurturing community where artists can share spaces and encourage each other. Communities are very important.

Have you ever wondered why Greece has so many great collectors and people who support both the local and international art scenes? Is it something embedded in your culture?

Historically the ancient Agora was a central location where thoughts were shared. People came to listen and learn with others. It was about being part of the creative process with music, theatre, and art. More than just collecting, it’s about the collective sharing of tradition. This is a significant part of our culture.

There is a tradition of collecting. In my case, collecting came from my family. We collect to enjoy and to share. Collectors are part of the community too. Greece has always encouraged the creative mind, with thinkers, collectors, and a culture of collective thinking and sharing, Greece fosters creativity.

Struth Thomas: Acropolis Museum, Athens, 2009, 203 x 163.5 x 6 cm. “Thomas Struth photographed the then newly opened Acropolis Museum, bringing to the surface the antique world which still lies beneath the building.”

And also, you always say that you do not “own” the works in your collection. It's like you are a custodian, and you enjoy sharing them with others because, in a way, the artists are the owners of these works.

Absolutely. We are temporary custodians. I have to mention another prominent collector, Mr. Dimitris Daskalopoulos, who demonstrated great generosity by donating a significant part of his collection to four museums. He is setting an example for many of us.

Have you ever thought about opening your own space?

I’m putting all my energy into other projects, and I think it's more useful this way for now. All the resources are distributed to different venues at the moment.

There are collectors who believe that a collection is alive as long as the person who created it is. Once they pass away, the collection becomes something entirely different and loses its vitality. Do you agree with this? From the viewpoint of a custodian, art doesn't have an owner and lives its own life.

Some collectors are no longer around but remain associated with their collections. For example, Stavros Niarchos' collection is legendary. He stipulated that his collection remain protected in its entirety. He was the biggest collector of Van Gogh and Impressionists. Eventually, his collection will be seen again, and he was perhaps one of the most important collectors of his time.

Many collectors have donated their collections, which often remain in museums bearing their names. Many museums, such as Tate, Beyeler, and our National Gallery were started with donated collections. These collections live on and continue to grow within a museum. However, there are many types of collecting. In the last 20 years, we've seen collectors who view art as a tool for exploitation. In a world characterized with greed - more possessions - art has unfortunately become a commodity.

For me, collecting is a passion that brings me joy. But I see the negative side of the art market. There's a problematic game around the art world that tends to give everyone a bad name.

I suppose you like to change the artworks surrounding you quite often.

Yes, I do. I change the artworks in my home once or twice per year. I maintain an office for managing my collection. The office is necessary for logistics, handling, works we lend to museums. We also manage an extensive file of information concerning the collection. I might forget to pick up my clothes from the laundry, but I’m much more organized with art. [Laughs]

Art is what makes me happy. After a long day at work, I turn to look at art. I am surrounded by an old painting of the island of Mykonos, my vacation island, and a group of works by Bia Davou and Nausica Pastra, female artists with mathematical minds. Women are very much mathematical minds, unlike popular myths. Art proves that women are equally capable as men in terms of being important artists, and they have a very important message to convey through their art.

Cosmadopoulos George (1895 - 1967): Mykonos, oil on hardboard, 41 x 35.5 cm. “This painting hangs in my office. A painting of Mykonos’ past, on a bright day, in a whitewashed street, leading to the port. It stirs happy summertime memories during the moodier days of winter.”

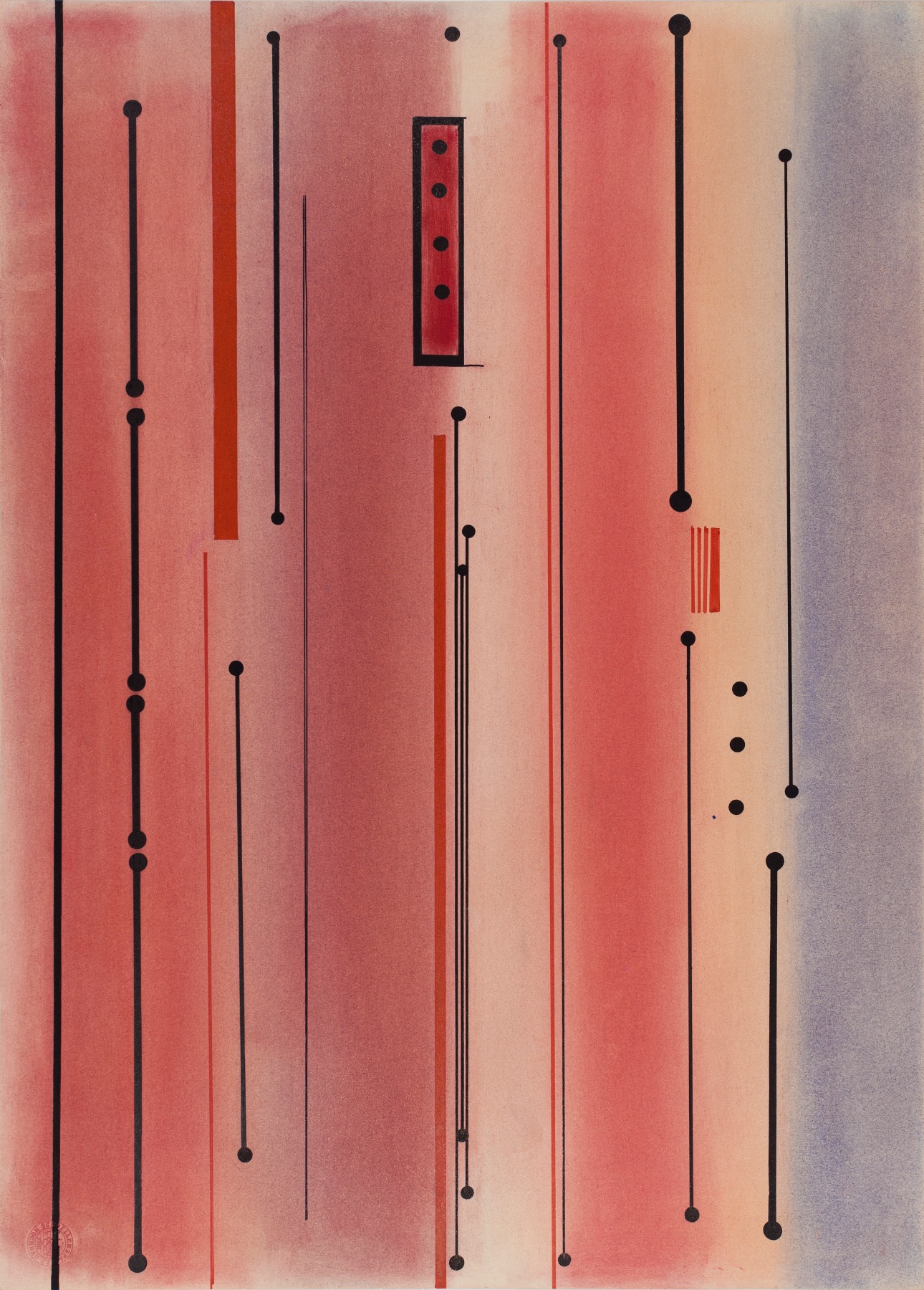

Davou Bia (1932 - 1996): Untitled, 1975 - 78, ink on paper, 70 x 50 cm. “Since the 70’s, Bia Davou was preoccupied with communication, the language of mathematics and

computers. She called her compositions “serial structures” based on the binary and the Fibonacci sequence.”

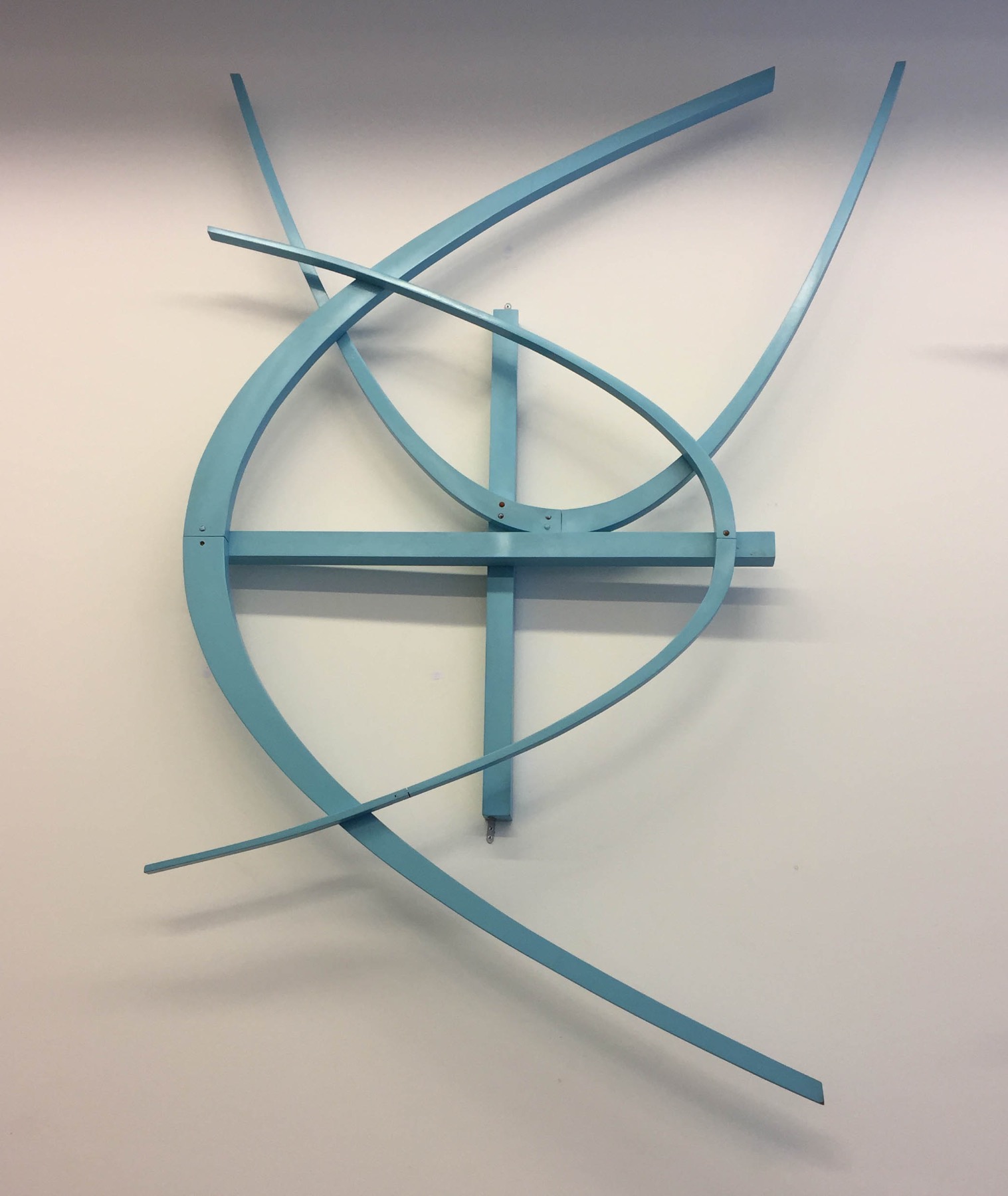

Pastra Nausica (1921 - 2011): Synartisis VII, Analogiques 3, 1982 - 1986, painted wood

120 x 270 x 25 cm. “Nausica Pastra experimented with geometrical forms and mathematical relations, combining circles and

squares, which she called “Analogic”.”

The focus on indigenous art was also very strong at this year's Venice Biennale. It's interesting that the reaction from the Western art scene was quite varied how to fit it into our established categories.

I have questioned the idea of craft as art. But now I think that craft should be part of art. Craft is something that we have never valued enough. Craft has many expressions and has always been an integral part of tradition and art making. We have dismissed it from art for so long. You can find crafting tradition in tapestries, basket weaving, embroidery, and more. All these art making mediums can convey powerful messages.

Was there a special moment when you recognized that you were a collector?

It takes a while for a collection to gain an identity. I remember being asked about my collection and I wasn’t sure how to react. I felt that a collection was very private. It took me many years to become comfortable speaking about collecting. I have had the honor to have met many exceptional collectors who helped me gain confidence as a collector myself. I have to mention some collectors who were influential, such as Barney A. Ebsworth, Dakis Joannou and Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo.

Do you think collectors are the ones who can make impact?

Collectors sometimes see trends before others do. For instance, many museums are now focusing on women artists. Collectors have been advocating for women artists for years.

I have seen collectors who have been outspoken about sexual identity, but their collections were initially seen as obsene. Now, the topic is mainstream. I've also seen collections that address themes of violence, such as gun use and bloodshed. Violence is a very difficult topic, but some collectors have focused on it intensely. By bringing together various works on similar topic, they create a powerful statement. Collectors have the capacity to confront current issues, supporting front runner artists ahead of institutions. Through their collections they are screaming "Look at this! This is a problem. Do something about it!"

Vlassis Caniaris (1928 - 2011):

Game, 1973, mixed media, 118 x 168 x 57 cm. “In this work of Vlassis Caniaris, the child’s game is a box of vacant promises. In 1973, this child’s future is ambivalent.”

To feel the power of art and to let it resonate, you need to find time to truly look at it. In this fragmented world, we are often too distracted to let that happen. It’s very difficult to teach another person how to look. What would be your advice?

I am happy that the EMST, the contemporary art museum of Athens, has become an integral part of the local art scene. Growing up in Athens, many generations, including myself, missed out on exposure to contemporary art. We have antiquities and history museums, but we didn’t have contemporary art museum.

Contemporary art is about the present moment.

EMST is a fun place to visit, to be inspired. School children have an additional museum to visit in Athens along with the archeological and historic places, which may suggest an alternative vision of the contemporary. EMST is now lively with visitors of all ages. Accordingly the National Gallery is also moving in the direction of addressing important current issues in dialogue with the historic collection. The latest show “Democracy” is exploring the pursuit of democracy in Greece, Spain & Portugal. It has received great reviews and attracting new visitors.

I’m pleased to see many young people in the museums. Clearly, there was a big audience that needed a contemporary art museum, and now they have the opportunity. So to me, this is the first step - going to the museum.

They ask me what they should look for in a museum. I say, “Look for nothing. Just walk around and notice how you feel.” You may not understand everything, but something might speak to you. It’s like poetry. Sometimes you come across just a few lines that resonate deeply with your life. Similarly, you might visit a museum and encounter something that makes you say, “Wow, that’s my life.”

Vlassis Caniaris: Untitled (Bicycle), 1974, bicycle and wooden floor, 70 x 250 x 160 cm.

Courtesy the Estate of Vlassis Caniaris and Galerie Peter Kilchmann Zurich, Paris. “Vlassis Caniaris, a bicycle sinking in the sea or flying in the blue sky?”

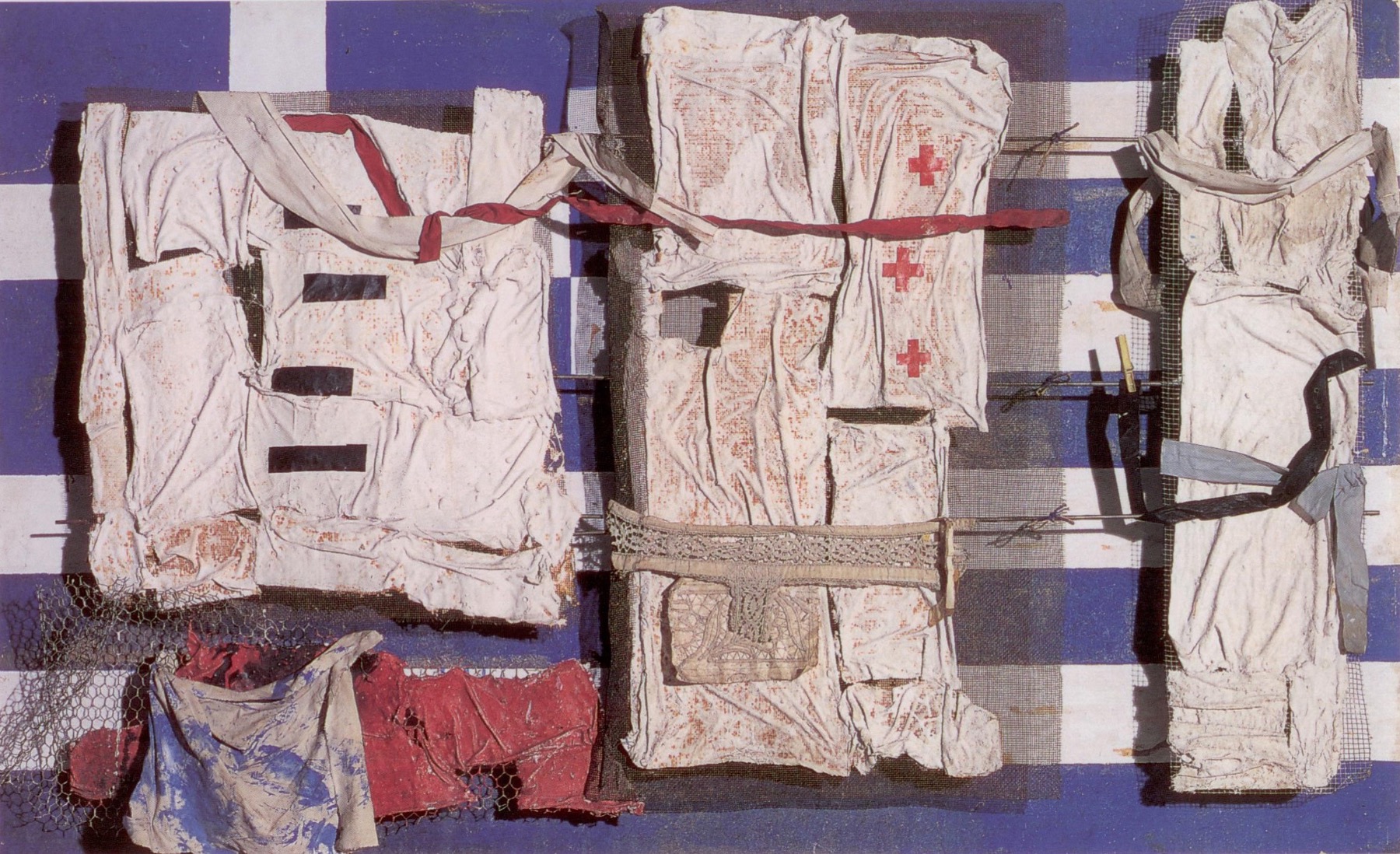

Vlassis Caniaris, (1928 - 2011): Untitled, 1964, signed Caniaris 64, mixed media, 110 x 180 x 25 cm. “Vlassis Caniaris is featuring in the background an image of the blue and white Greek flag, adorned with objects from past injuries, experiences, but also adding cast for healing and hope.”

I remember seeing a work by Vlassis Caniaris. A real bicycle missing the front wheel, sinking into a blue surface. Caniaris, an Arte Povera artist from Greece, also lived in Italy and later emigrated to Germany. He, like many, had to move to make a living during his hard times. This work reflects his feeling of despair. The blue field could represent the sky, the sea or the colour of his country’s flag - I’m not sure - but it conveys a sense of being unable to move anymore. It has incredible layers of meaning.

I was fortunate to meet him many years ago. He didn’t speak much, like Jannis Kounellis, but his work is immensely powerful.

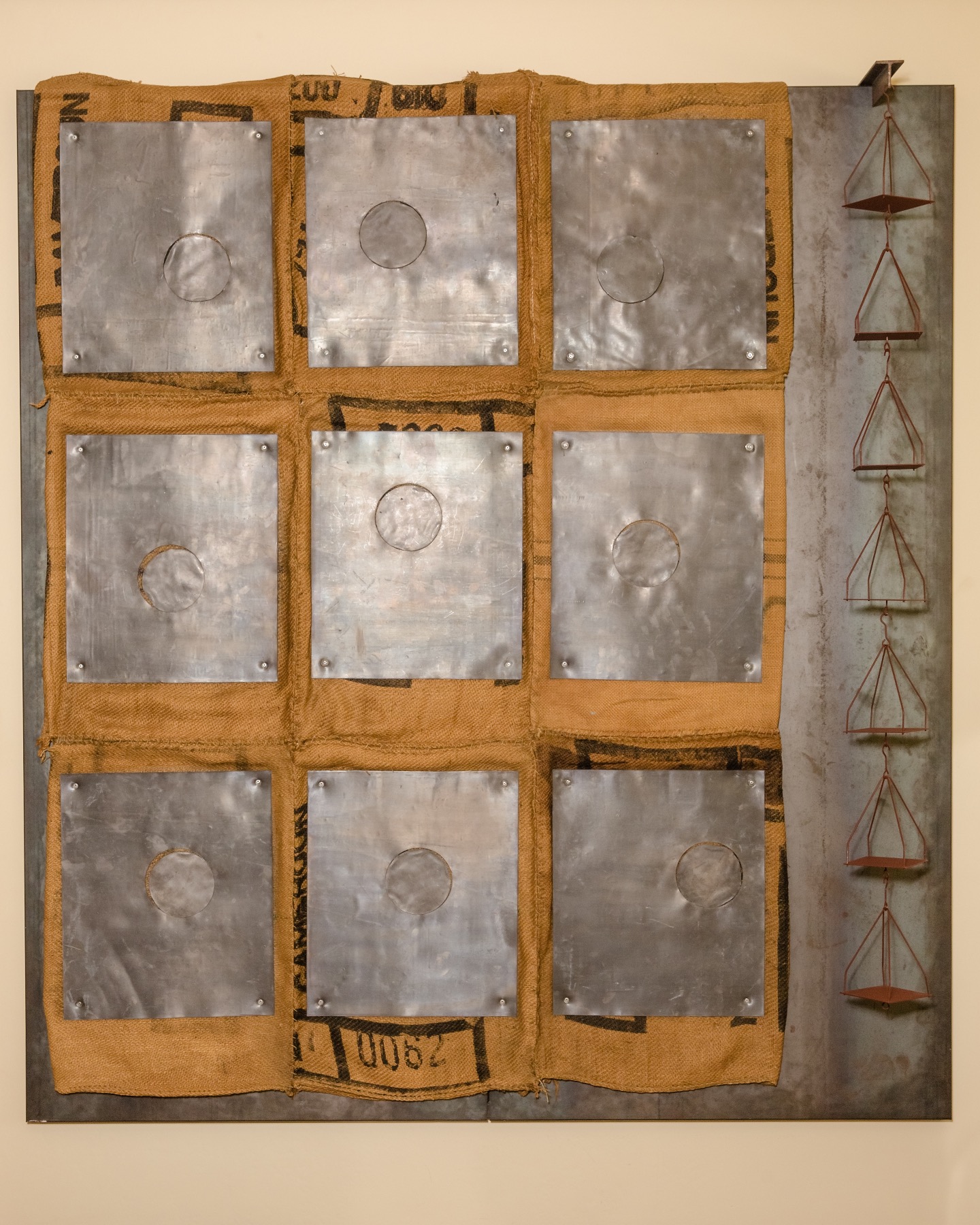

Kounellis Jannis (1936 - 2017): Untitled, 1986, steel, burlap and lead, 203.2 x 180.2 x 30.5 cm. “Steel, burlap & lead, the ingredients of memories from a tumultuous childhood in war ravaged hometown of Piraeus, where Jannis Kounellis was born. That same year my father was also born in Athens.”

Kounellis was a teacher to me. I met Jannis Kounellis on different occasions. I had heard him speak about his work. He belonged to the same generation of my parents, who as kids experienced the brutality of WWII and who had to move to another country to survive. He moved to Rome from Piraeus, his birth place. His canvases which he called “cadro” were made of steel, the size of a marital bed. They encompassed his entire life, the memory of destruction, bombs, dust and death.

Someone once asked him why he doesn’t draw what he sees. He replied, “I am doing just that.” Yes, Kounellis was indeed my art teacher. He taught me how to see.

Thank you!

Irene Panagopoulos. Photo: Pauline Niarchou. Artwork by Pastra Nausica (1921 - 2011): Sphere ll, 1977 - 1988, iron, 30 x 31.5 cm.