Art is all around us, but not everyone sees it

A conversation with Petter Stordalen, Norvegian entrepeneur, collector, philanthropist and environmentalist

On the way to my meeting with Norwegian entrepreneur, collector, philanthropist and environmentalist Petter Stordalen, my mind wandered to thoughts about the concept of time and its illusory loops. This will be our second meeting – I first interviewed him eleven years ago, for the first edition of Arterritory.com's Conversations with Collectors. The Thief – a hotel-gallery exhibiting 105 pieces of art and back then the flagship of Stordalen’s hotel empire – had just opened in Oslo. Its lobby was home to Richard Prince's legendary lithograph Cowboy - The Horse Thief; other represented artists included well-known names such as Antony Gormley, Niki de Saint Phalle, Julian Opie, Tony Cragg and Peter Blake, among others. Some of the pieces were from Stordalen's private collection, while others were from the Astrup Fearnley Museum next door. The Thief also was the only hotel in the world with its own art curator: Sune Nordgren, the former director of Norway's National Museum.

At that time, Stordalen's hotel chains – Nordic Hotels and Resorts, and Nordic Choice Hotels – comprised 171 hotels and 12 000 employees; today, the number of hotels has reached 235, the number of employees 16 000, and the chain has changed its name to the Strawberry Group. Stordalen has now added the Kämp Collection Hotels in Helsinki to his portfolio, as well as Sunclass Airlines and the travel company Ving.

Petter Stordalen greets me with a wide-open smile, dressed in light blue jeans and a matching loose shirt; he is bursting with energy, direct, open, and full of optimism. It's a sunny day in Oslo, the city's parks and waterfront are full of picnickers, and it feels as if these eleven years had never passed. At the same time, something is different: as we both later discover in conversation, if someone had told us then that war would break out in Europe in the next ten years, we would have dismissed it as an impossible scenario. Likewise, a prediction that an out-of-the-blue global pandemic would paralyse and temporarily bring to a complete halt our routine ways of life (and thereby also readjust our value systems) would have been just as incomprehensible to us.

We meet in the courtyard of Strawberry headquarters – it is full of artworks, with tables in the middle where employees either sit at computers or are deep in conversation. Petter says the historic building has grown too small in size, but everyone loves it so much that no one wants to part with it, and as a result, he has expanded the courtyard and adapted it for use in a variety of weather conditions.

Our conversation is about art, and we start with the book about his collection that Stordalen is currently working on with Sune Nordgren. It should be mentioned that the collection itself has doubled in size over the years. But in the first few sentences, I notice that there is another participant in the conversation: time. The past, present and future are directly and abstractly intertwined in its canvas. Art is still present, but it has somehow acquired an additional voice and significance. Like Stordalen's disarming smile, which, on deeper inspection, has both over- and undertones – they have been shaped by what has happened and what has been experienced. As Petter will say later in our conversation, ‘Art is all around us, but not everyone sees it.’

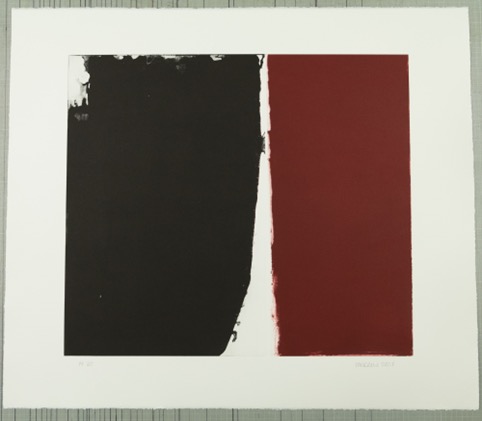

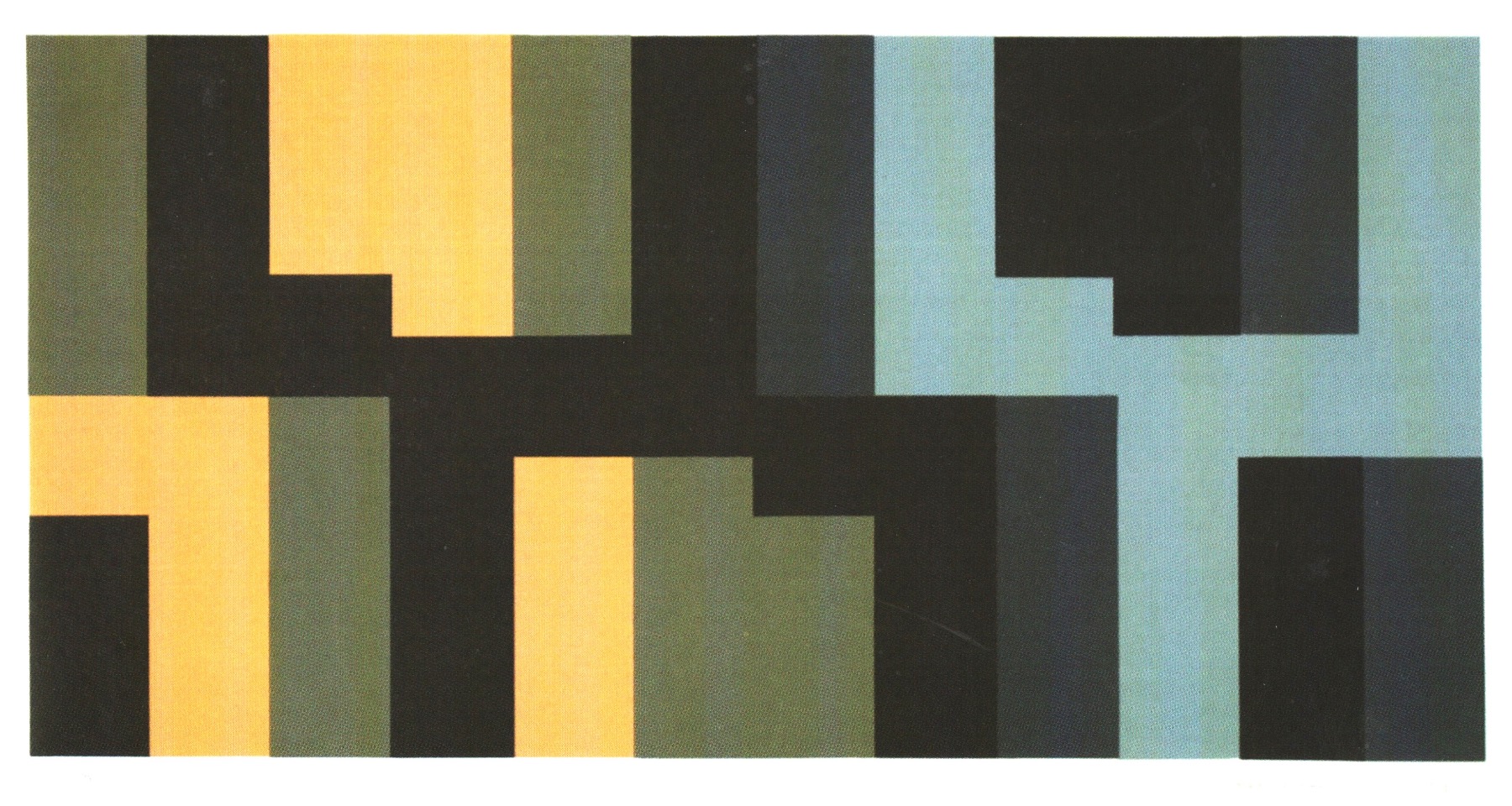

Gillian Ayres, "Mirabell", woodcut, 2011, Villa Copenhagen.

He still starts every day with a morning run and, as his Instagram account with 326K followers indicates, he still is ‘the flashiest Scandinavian on the planet’ (a title awarded to him by Forbes). During these past eleven years, he has also faced the biggest crisis of his life and business so far – the pandemic completely paralysed hotel operations world-wide, but contrary to predictions, Stordalen's empire emerged as a success story. Moreover, with a new identity as the Strawberry Group. It just so happened that the new strawberry logo was the first thing I noticed when I flew into Oslo. It embodies smiles, cheerfulness, and the whole package of bubbling vitality that everyone feels when they bite into the first temptingly red strawberry of summer.

In a sense, Stordalen has returned to his roots – the strawberry is a mythological element in his success story. While selling strawberries at age twelve, his talent for the business earned him the title of ‘Top Norwegian Strawberry Seller’. In addition, strawberries are also one of the key lessons of his life: he once angrily complained to his father that other sellers had bigger and more beautiful strawberries, to which his father replied, ‘Sell the berries you have, because they are the only berries you can sell’. This became ‘The Strawberry Philosophy’, a paradigm embodying bold ideas and a vector of purpose whose underlying genesis is continuity and reality-based positivity.

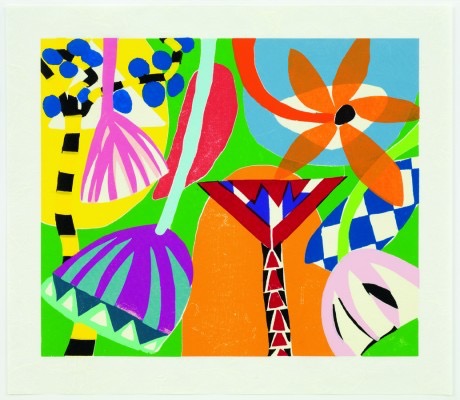

Gillian Ayres, "Tivoli", woodcut, Villa Copenhagen.

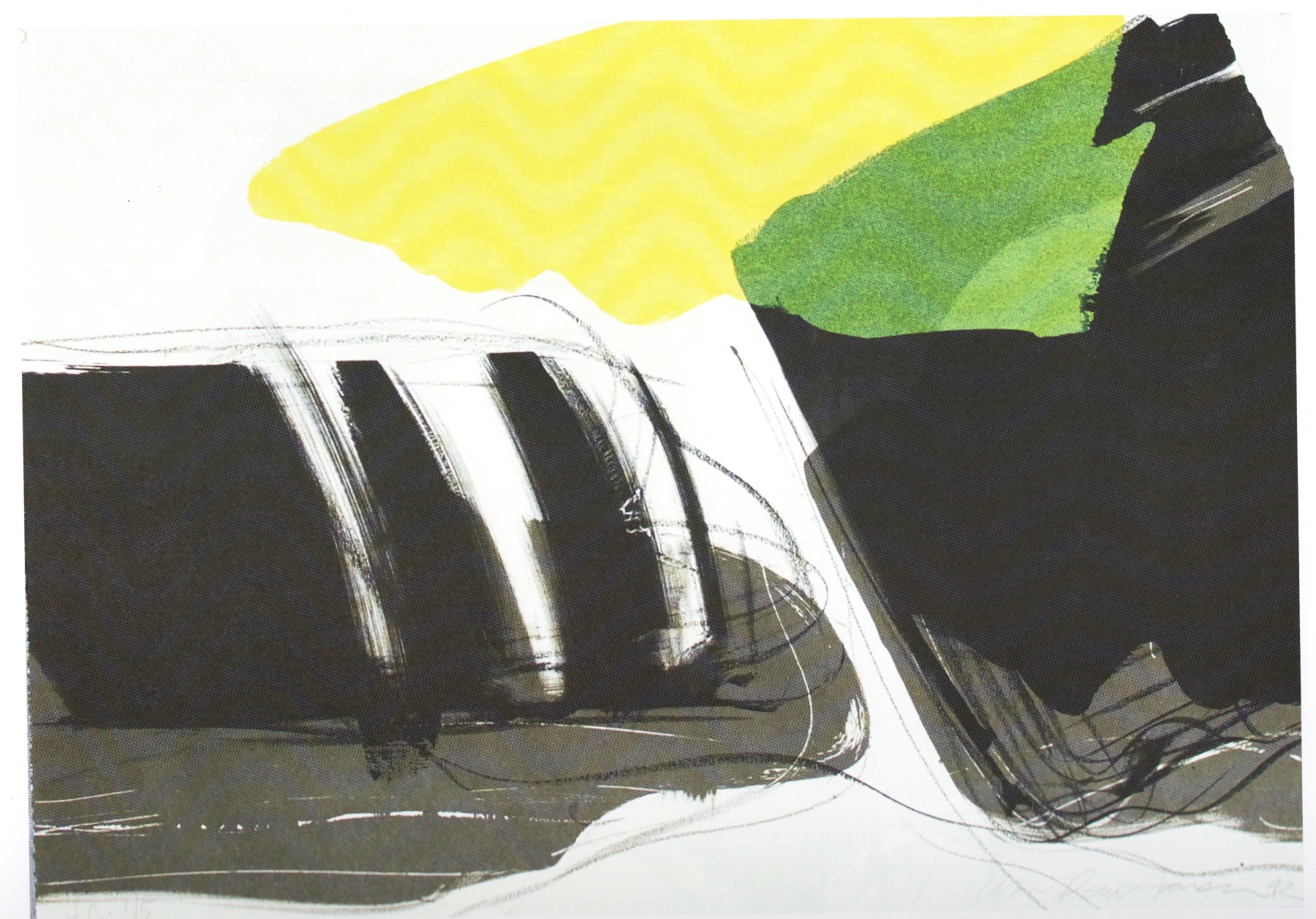

Stordalen says he is even more optimistic now than at our last meeting. And I know he’s not being facetious. I doubt there are many who, in the face of a global pandemic, would have dared to make the decision to open Villa Copenhagen exactly as the hotel was originally conceived – with a multi-million-euro art collection featuring works by both local artists and internationally renowned artists such as Jaume Plensa, Per Kirkeby, Gillian Ayres and Ian McKeever. ‘Not everything is about money. It's about whether you believe or you don't, and I'm a believer.’

We agree to meet again in eleven years.

I know you are working on a book about your collection. Why do you feel it is the right time? Can we say that your collection has reached some kind of milestone? As far as I know, it has almost doubled in recent years. Has it also changed direction, become more focused, or become more theme-oriented?

Yes, it is more focused now, and that's due to Sune's job. Even though he will say that we are more equal than 10 - 15 years ago, that's not true. Sune is more important to me today than ever. Every year I've worked with Sune, I feel like he knows even more, while I feel like I know nothing - and I kind of like it.

Petter Stordalen and Sune Nordgren in front of "Mississippi River Blues" by Richard Long at At Six in Stockholm, 2020. Photo: Eivind Yggeseth.

I was thinking about meeting you, and while I was running this morning, I accidentally noticed something new. It made me reflect on why art is important in our daily lives. I run every morning, usually following the same route, and where the cows usually are, there were rhinos. I don't know the material, and I don't know the artist, but it's very beautiful. Look! (Petter shows a picture of two white rhinos on his iPhone – U.M.) I read that there had been some discussions about it because rhinos are not native to Norway, they are dangerous, etc. I viewed it from different angles and felt super happy. Then I saw some more, and as I was listening to the BBC on my iPhone, guess what the big topic was?

Rhinos!

Yes, a rhino mounting a car in Charlton with a traffic cone on its bonnet. Banksy has released his animal series across London. The last one was a gorilla at the London Zoo, which was the most popular. People wanted to protect it - it was something precious, like an important moment in their history.

I think there were nine works in total, and not only did they attract crowds, but they also sparked many discussions - what is the deeper meaning of these animals? That’s what I like most about art. It’s not so important whether I like the particular artwork or not, but that it changes the surroundings. It gives me a few minutes to reflect on rhinos, diversity, and the importance of species, even those as dangerous as rhinos. And maybe that's the most important thing art can do - start discussions.

So, I think the collection and the idea of the book - which we will have in all our hotels - is about that: art is a part of who we are.

As far as I know, the last thing you bought is the renowned Imprimo art graphics collection, which belonged to Hotel Kämp.

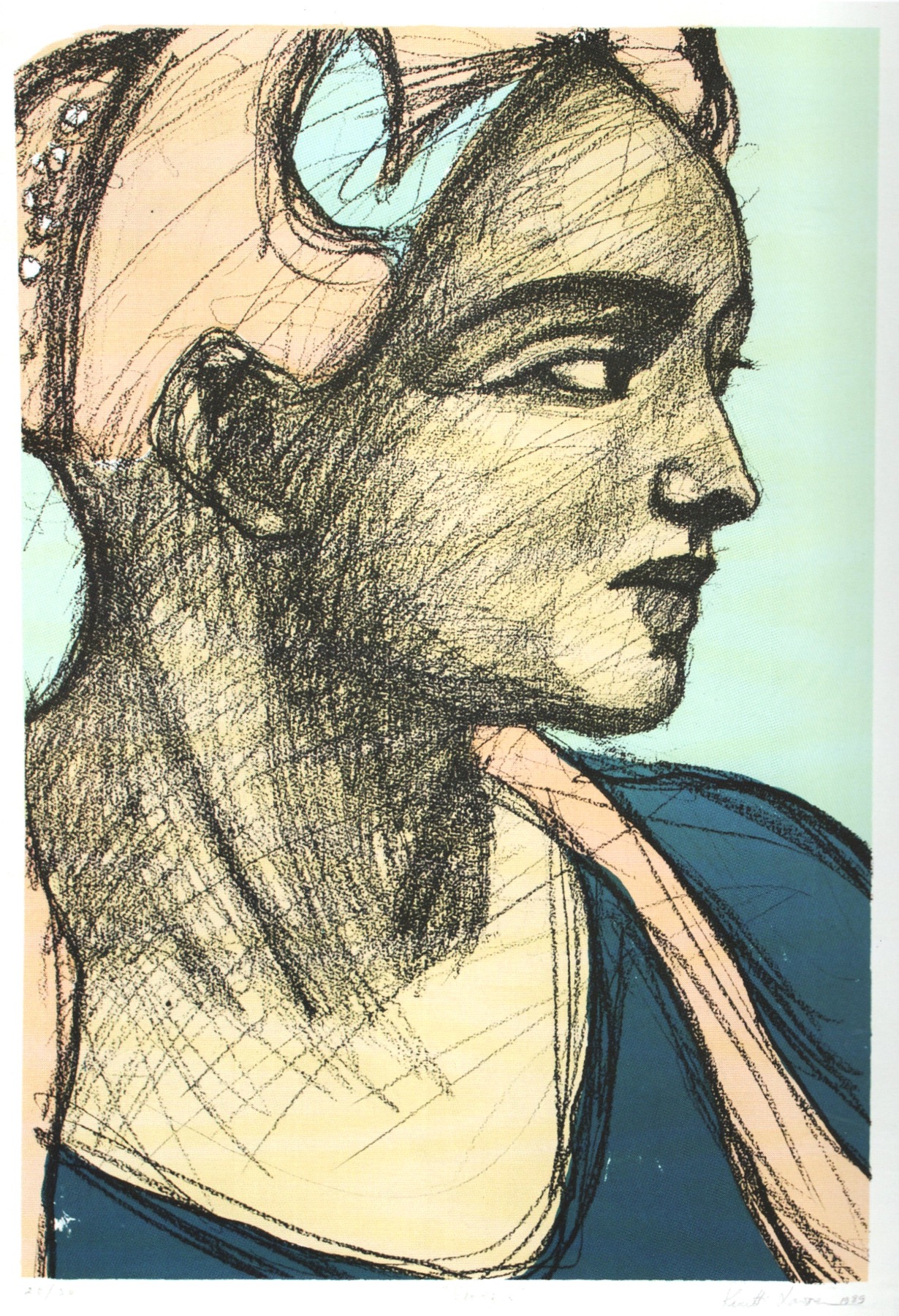

It's a huge collection. The Kämp Hotel, which opened in 1887, has been a place for artists, musicians, and everyone in between for decades. Jean Sibelius, Eero Järnefelt, and Akseli Gallen-Kallela all spent much time at Kämp. It housed something called the Imprimo Collection, which was the first Finnish graphic art collection. It began in the 1980s and continued to grow with new additions until 2003. Today, the collection consists of 450 works, mostly prints and graphic pieces, featuring some of the most famous Finnish artists. We purchased it just before the pandemic, in 2019.

After the pandemic, when I was back in Helsinki, I thought, "We bought this collection, and it cost a lot, so what exactly is it?" I wasn’t sure at first because I had only seen a few artworks hanging in different rooms. Then I realized that the few works we have in the hotel are just a fraction - this is a collection of 450 different pieces. It's massive and it's beautiful!

Now, as part of our 120-million-euro renovation, we plan to bring the entire collection - all 450 works - back into the Kämp Hotel so that every room will have a few pieces on display. Everything will be finished by late 2025, but the more I looked at it, the more I was like, "Wow." The history of these around 75 artists who literally gave everything to represent this period in Finland is incredible. This is what the best artists were doing at the time. Let’s have one collection, and Kämp bought it, and I bought it when I acquired Kämp. Most of it is just stored away. So, we will re-frame everything, catalog everything, and bring it all back into Kämp.

Kuutti Lavonen, 1988. Lithography. From the Imprimo Collection at Kämp in Helsinki.

Ulla Rantanen, 1992. Lithography. From the Imprimo Collection at Kämp in Helsinki.

Pekka Ryymänen, 1993. Lithography. From the Imprimo Collection at Kämp in Helsinki.

When we last met almost 11 years ago, you mentioned that you always follow the same pattern - you always want to climb a new mountain. Back then, it was art. Is art still this mountain?

Yes, there is always a mountain to climb, but I would say that storytelling has become increasingly important. I was at At Six in Stockholm, where we have a beautiful sculpture by Jaume Plensa. It's made of white marble, and before placing it there, we had to reconstruct that part of the staircase because it couldn’t support three tons of marble. But if you see it today, it's absolutely stunning, and you’d think the entire space was designed around this piece of art.

I was there to go to the gym, and I noticed five people standing around, taking photos - not of the hotel, but of the sculpture. They were speaking Spanish and were so enthusiastic about it. It was like Ronaldo was there. But it wasn’t Ronaldo - it was just a piece of marble. Then they told me, "This is our artist! This is Jaume! He’s from Barcelona."

And I told them that I even have a piece by him in my apartment in Stockholm. It’s beautiful, and it reminds me of all the things I've done with Jaume - from Copperhill to Villa Copenhagen and Post in Gothenburg.

Art is all around us, but not everyone sees it.

Petter Stordalen with marble sculpture "Mar Whispering" by Jaume Plensa at At Six, Stockholm, 2018. Photo: Eivind Yggeseth.

In recent years, we have talked a lot more about the impact of art on our mental and physical health. The World Health Organization officially recognized the therapeutic potential of the arts in 2019, based on more than 30 years of scientific research. There are ongoing programs of "arts prescription" and "museum prescription." By including art in your hotels, you have been "prescribing" it to your guests for years. What is the role of art in our mental and physical well-being, and is it recognized enough?

I feel this is beyond my pay grade (laughs). But based on my experience over the last 24 hours and the discussion Banksy has sparked about big questions like diversity and sustainability, I can say this: When I see these rhinos in Norway, in a garden where cows usually graze, it stirs something inside me that makes me even happier. If you ask me why, I don’t really know.

I also can’t explain why I took a detour just to see them. I wasn’t the only one; I know that most people who are there at that time in the morning did the same. For instance, there are always two cyclists who pass by nearly at the same time. They also took the detour - cycling around the rhinos, turning around, and then cycling back. I’m 100% sure they started discussing why the rhinos are there. And did you know there are only about 200 white rhinos left in the world?

So, to answer your question, I’d say the logical answer is yes. Do I have scientific evidence? No. But there are many things in my life for which I don’t have scientific evidence, such as when I started something called “Endelig Mandag!” (Happy Monday).

I do it every Monday because I think most people say, "Oh, it’s Monday." I was on a radio program in Gothenburg, which is the biggest station in the city, and they had been talking about Friday since Tuesday - like, "Oh, it’s only three days left," then "Only two days left," and "Tomorrow is Friday." When I was there on a Friday, they asked me, "Peter, are you happy it’s Friday?" I said, "I don’t like Fridays. Why? I love Mondays." And that’s how “Happy Monday” started.

I began with one Instagram post, and thousands of people responded positively. I said, "I just love everything about the beginning of a new week. Everything that starts, everything that feels like clean sheets. Okay, last week might not have been so great, but this week is a new beginning." I kept it going, and now even on the radio, they say: “Happy Monday.” I also wrote a book about it called Happy Monday.

You need to include something like a “happy hour with art” as part of Happy Mondays.

Art doesn't always need to be "happy," because art can spark discussions. I think we talked last time about Charlotte Thiis-Evensen's video installation Individual Freedom at The Thief Hotel, which features three Somali sisters slowly taking off and putting on a hijab. I remember telling you that until then, I had never really reflected on when they must make the decision to wear the hijab or not. At what age? Are they pushed by their parents, or do they make this decision themselves? So sometimes, it's good to have art that makes us reflect on certain things. That's valuable too.

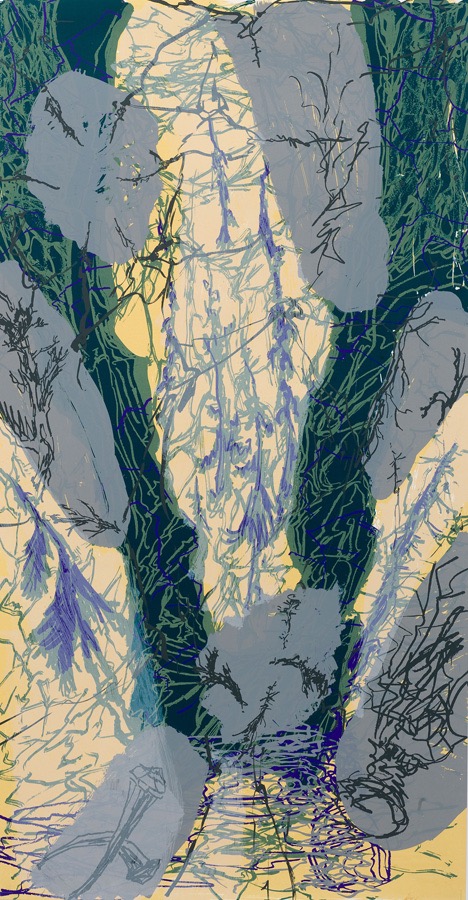

Ian McKeever, "etching", 2018, Villa Copenhagen.

When we last spoke, your garage housed huge photos by Axel Hütte. They were from the rainforest, as a reminder that rainforests are the lungs of the world.

I've since moved them to Copperhill Lodge. I realized that in the garage, it's just me, the dog, and a few others who see them. At Copperhill, many more people will get the chance to experience these works.

Climate change is the biggest challenge we are facing right now, and it seems we are still stuck in this fight.

Yeah, but you need to be a bit more optimistic. The focus today is very different from what it was 10-15 years ago. I remember when I was talking to you back then, and Gunhild - we are now divorced, but we’re still close friends - she was starting something called Eat because if you don’t fix food, you won’t fix anything else. The way we produce food is crucial.

Many years later, they started collaborating with The Lancet, probably one of the most renowned medical health publications, on an initiative called the Eat Lancet Commission One. This was meant to establish guidelines for food. Now, Eat Lancet Commission Two will be released in a month or two, which will set new global food guidelines. The Stordalen Foundation was the main supporter from the beginning. It’s like a startup, and today, together with The Lancet, they’ve been involved with the United Nations. The best experts in the world are working together to say, "These are the guidelines."

I know having guidelines is one thing, and putting them into action is another, but we need to start by asking, "What do we need to do?" This is what we need to do to fix it, and if we don’t address this, we’ll never fix it. I don’t believe in a single silver bullet to solve everything. It’s about thousands of small things we need to do, and I see progress every day - more electric cars, better environmental practices. We are much better at taking care of the environment than ever before. And yes, I read all the articles that should make me feel depressed, but I’m optimistic. We will fix it.

I remember when I was growing up, there was a big concern about the ozone layer being damaged by chlorofluorocarbons in spray cans and refrigerants. We feared that if it got worse, the sun would turn the Earth into a barbecue. But we fixed it with guidelines, and by choosing not to buy those products, we made a difference. The same goes for plastic in the oceans. When my CEO of 25 years heard on the radio that there might be more plastic than fish in the oceans, even though it wasn’t true, he said, “Petter, how difficult could it be? Let’s just eliminate all single-use plastics in our hotels within 12 months.” And we did - 90% of it, anyway. But the media focused on the 10% we hadn’t fixed yet, like finding a plastic cup at one hotel. I said, "Yes, we eliminated 90% of single-use plastics. That’s 90% better than zero, and we’re working towards 100%."

It’s easy to focus on what’s wrong, but there’s also a lot that’s going right. Airlines, cars, everything is moving in the right direction. Is it going fast enough? Not at all, but we are making progress.

You think we mostly need to change the frequency from pessimistic to optimistic, and then maybe we could overcome the world situation as well because, besides climate change, we are also facing war.

It's a massive challenge. If you had told me last time we met that we would have a war in Europe, I would have said there was zero chance. It’s more of a philosophical question: What do you think? Is it optimists who have built the world, giving us all the new things - mobile phones, TV, electricity, everything? Or is it the pessimists? I think it’s the optimists who have built the world. New inventions make the world better. I’m a believer. I know it’s sometimes hard to be an optimist, but I’ve decided - I’m an optimist. Always? No. But in the bigger picture, yes, I’m an optimist.

I also know that the war will end, and that it will never end by fighting. It will end at the negotiation table. And I think even now, when things seem totally crazy, you can look at what’s happening as either an escalation or a preparation for negotiation.

Speaking of war, we tend to forget about Sudan and what’s going on in Africa. Sudan is probably facing one of the biggest food crises we've seen in Africa in years. And do you read a lot about it? No. You read about Ukraine, you read about Gaza. But I’m still an optimist.

While the hospitality industry struggled greatly during the pandemic, your company emerged even stronger. In a way, you used the crisis not only as a challenge to overcome but as a teacher and a friend.

Yeah, even though it was the biggest crisis of my life. When we were facing the lockdown, our number one priority was the people - we had to take care of them. The culture we have is unique. We had to lay off thousands - 8,000 in the first round. It was brutal. Today, we have 20,000 employees. But even in the middle of the worst part of the crisis, you have to try to change the dynamic, because if people stop believing in the future, that’s more dangerous than Covid.

So, what do you do? You’re losing tons of money every day. There are articles in the newspapers saying, "No, no, Petter will never manage. It’s too much. It’s airline companies, it’s a travel company, it’s new hotels, it’s everything."

The very last thing a company would do in a situation like this is start massive innovation. So, what did we do? We asked ourselves a question - the pandemic will end, and when it does, the world will have changed. We will have changed. If I give you 245 hotels, 20,000 employees, and the best culture in the industry, and you could design this company anew, what would you do? Forget everything from before, forget about brands, names, tech - what’s the new thing?

It literally started with four people. But because we couldn’t be together, four became 20, then 100, then 200, and suddenly, within months, the dynamic totally changed. We redefined everything. People started talking: "They’re planning for a new future. They’re using hundreds of people to plan something brand new. They’re spending money." This created a super optimistic atmosphere.

That’s how Strawberry was born. We’re putting Nordic Choice Hotels back to the past and becoming Strawberry, building on our history, culture, and heritage.

Petter Stordalen at sculpture "Verkehrtes T" by Franz West at Strawberry headquarters in Oslo, 2018. Photo: Eivind Yggeseth.

You know, our turnover in the Norwegian economy was 11.5 billion NOK in February 2020, when the pandemic hit. Today, four years later, it’s 18.5 billion NOK, and next year it will be over 20 billion NOK. The top line is better, the bottom line is better, the culture is better, and it’s largely because even in a crisis, you can turn things around. When it comes to optimism or pessimism, you need to hold two thoughts at the same time.

Yes, the costs and losses were brutal, but most companies, when they’re in a crisis like this, only focus on laying off more people and cutting costs. But that only takes you halfway, because the rest of the people will start thinking, "Is it me next time? Is it my job?" and their focus will shift. So the most important thing to do is to help them understand: no more layoffs - we’re planning for a new future. We need everyone who was laid off, and we need everyone working right now. So, when the pandemic was over, we brought back all 8,000 people.

At that moment, the Omicron was emerging, and the Norwegian government announced a new lockdown just before Christmas - for no reason at all. If you're a capitalist, it might seem like a good idea to lay off those 8,000 people again just before Christmas. But if you have a heart, that’s too brutal. So, I called some friends I had at WHO and asked, "How serious is Omicron?" They said, "Petter, it’s like the flu, and it’s already over. This lockdown isn’t necessary. It’s a panic."

So, we didn’t lay off anybody at all. When the government decided to reopen Norway, we were literally the first to say, "We are back." We did everything at once, and I think that changed the company forever. You face crises in your life, in a company, in all aspects of life, but you can use - not all, but most - of the challenges that come with a crisis to your advantage. In every crisis, there’s an opportunity to think differently. Use it.

Yes, we lost money. Yes, hotels were closed all over the Nordics, and people were not allowed to travel. And what’s the last thing you would do in such a situation? Plan for more hotels, new brands, new tech - invest a hell of a lot of money and just go for it.

Do you remember any moments during that time when you approached a work of art, not for help, but perhaps for inspiration?

I remember we had a huge discussion about Villa Copenhagen. I was burning cash like crazy every day, and we were only doing the things that were absolutely necessary. We debated whether we should open Villa Copenhagen in the summer of 2020, and before that, whether we should spend millions on art. I thought, "Art is an important part of the hotel." I’d envisioned the Jaume Plensa piece hanging there since I saw the first drawings. The pandemic would eventually end, but the art would still be there. If I opened the hotel without it, it wouldn’t feel right. So, I told Sune to do exactly what we had planned. And so we did - and it’s beautiful. It’s a kind of signature. Not everything is about money. It’s about whether you believe or you don’t, and I’m a believer.

Petter Stordalen with hanging bronze sculpture "Minnas Words" by Jaume Plensa at Villa Copenhagen, 2020. Photo: Max Lindhardt.

In a way, with Strawberry, you’ve returned to your roots as well.

Yes, and not only that. All the branding experts told me, "You’ve spent 25 years building Nordic Choice as a brand, and now you’re changing it? Introducing a new brand will take another 10 to 20 years to build." But I was thinking, it’s a different world, it’s a different company, and we’ll see. I knew I would have some opportunities to get the brand known much faster.

Then, the National Arena, a multi-purpose stadium in Stockholm, needed a new brand sponsor. We bought the naming rights and renamed it Strawberry Arena. It was all over the news. So, when artists like Bruce Springsteen or Pink came, they were performing at Strawberry Arena. The new football matches were happening at Strawberry Arena. Signs were everywhere.

So, we fixed it - most of it, 80% - in five months. One of the branding experts said, "It might be wrong, but everybody knows the brand Strawberry now." And honestly, I think I was quite happy and optimistic the last time we met, but I’m even more optimistic today. I’m more optimistic on behalf of the world, on climate change, and on most topics. I think the world is moving in the right direction. We have some bumps in the road - the wars, Gaza, Ukraine, and, of course, things going on in Africa. But we will fix it.

Do you think collectors are the ones who can make an impact and have a voice in times like these? A well-known collector once told me that collectors have the capacity to confront current issues, supporting pioneering artists ahead of institutions. Do you agree?

A tricky question, but certainly every individual should have a voice, collector or not, and a responsibility to act for optimism and peace. Buying younger and pioneering art ahead of the institutions is obvious, since collectors should also afford taking the risks, it involves.

Do collectors also have a responsibility?

Collecting art can perhaps not change the world, but supporting public, professional and progressive art, will at least not make it worse.

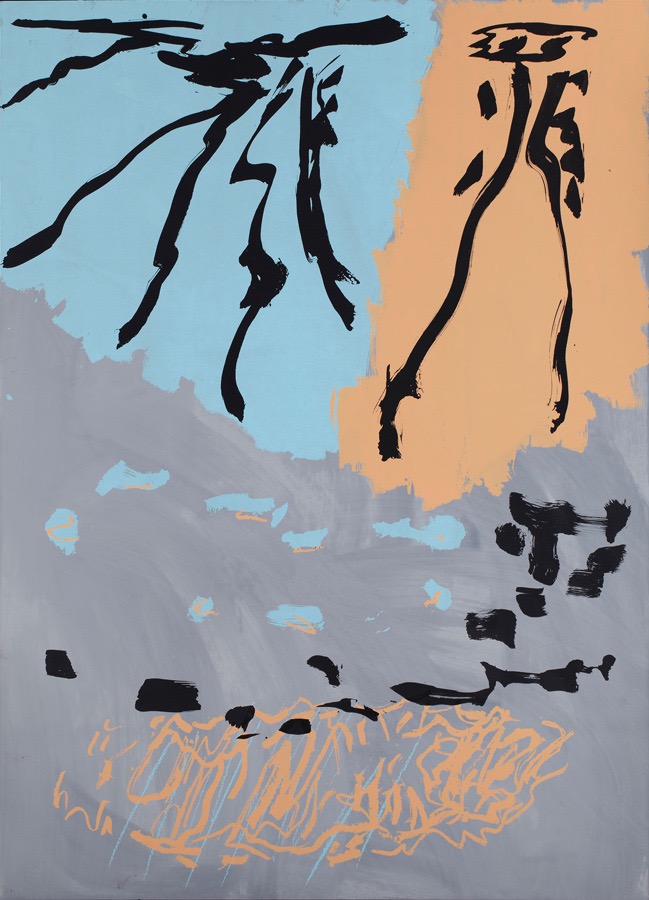

Per Kirkeby, silkscreen, 1996, Villa Copenhagen.

In your hotels, you work closely with museums. The Thief Hotel collaborates with the Astrup Fearnley Museum, while Clarion Hotel Oslo partners with the new Munch Museum. What are the benefits of this cooperation, and how do you see the role of museums in today's social ecosystem? Is it changing as well?

Yeah, it’s changing. Museums are institutions, but they can be a bit conservative. I think they would gain a lot by being more open. Like, why can't they take their art out sometime - not just to other museums, but out into the world, like hotels, schools, or universities? I know security is a concern, but honestly, that’s easy to fix because it would create more attention. People would be more curious, like, "Oh, what’s this?"

We had a huge discussion about the New Library in Oslo. Building a new library now might sound like a strange idea. I mean, I can access 2,000 books on my iPhone in a matter of seconds, so spending 4 billion NOK on a new library might seem unnecessary.

But you know what happened? Most people would think, "Who would go to the library?" Well, everyone - it’s packed. Sometimes there’s even a line of people waiting to get in. Because what’s a library? It’s a place where I can go, work, be inspired, borrow books, or just read.

The New Oslo Library has been a massive success, and I think for a city, museums and cultural institutions are super important. Oslo has changed significantly due to the new National Museum, the Munch Museum, and the Opera House.

Per Kirkeby, silkscreen, 2009, Villa Copenhagen.

I was in Barcelona recently. You know, the first thing I wanted to show my girlfriend was the Sagrada Familia. I first visited Barcelona when I was 16 or 17, backpacking. The city today has never been better - it's never been cleaner, more beautiful. The whole seaside area is absolutely stunning. It’s open to everyone.

When I went for a run early in the morning from my hotel, I ran down La Rambla, and it was super clean. Just 12 hours earlier, it wasn’t. They had cleaned it, and it smelled like flowers. I realized that they must have added some floral scent to the water they use for cleaning because I saw the machines, and it really did smell like flowers. As I was running, I thought, "Wow."

Then I took my girlfriend to the Sagrada Familia, and it’s only four years away from being finished. I asked a local why it took so long, and they told me that Gaudí had this idea that he didn’t want sponsors. People should pay to visit the Sagrada Familia, and that money would be used to build the next part. That’s why it’s taken nearly 50 years. At first, I wondered why he did it that way, but then I understood - the idea was that everyone should feel like they’re a part of it. They’ve contributed some of their money, so they have a stake in it.

And then, what started as a question turned into admiration - what a beautiful idea. Gaudí probably knew it would take 100 years, but now it’s almost finished, and it’s insane how beautiful it is. I make a point to see it every time I’m in Barcelona. I’m not even a religious person, but I want to visit. I don’t know why; it’s just beautiful, and I know I’m not alone in feeling this way. And now, I even have my own history with it.

Everything is inside of us.

Yeah, that's the same with the rhinos. I had rhinos on my run, and Banksy had rhinos in England. The London Zoo protected Banksy's gorilla like it was an endangered species, and that makes me happy. And we need happiness maybe more than ever.

Your life is symbolically connected to strawberries, which, by the way, contain 92% water; we humans contain 75%. Water is essential for life - there is no life without water, just as there is no life without art and human creativity. Have you ever thought about how the surrounding waters here have affected the way you view the world and art?

We Scandinavians have the forest and clean waters in our DNA, and my motto has always been clear: there is no business - and no art - on a dead planet!

Are you still buying with your heart?

I'm still buying with my heart. I still feel that Sune is more important than ever, particularly with the Kämp collection. A hotel is also about storytelling, and I know it will add something new. It's real, it's genuine, and it's Finnish, like people who simply wanted to contribute something for the future. And now it's been in the storage, but I don't think art belongs storage. I think everybody should see it.

Thank you!

* The sculptures of the white rhinos are part of Italian artist Davide Rivalta's solo show “Come si aspetta ogni ritorno” (How We Await Every Return) in the park of the Oscarshall Royal Palace on the Bygdøy peninsula in Oslo.