Don’t Say Hop

Alexandra Artamonova

27/02/2017

«On Saturday, as usual, the whole local gang came together. The older ones formed a little circle and kicked the ball around. Hit by a toe in a well-curled pass, it was flying close to the ground. Everybody was already soaking in sweat but no-one felt like taking off his Sunday jacket or blue knitted jumper with black or yellow stripes and losing face in front of the wet-behind-the-ears brats gathering around.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, Ragazzi di Vita

1.

Gosha Rubchinskiy, age 32. A streetwear designer; photographer; director. So, what else? A graduate from the College of Technology and Design; at some time in distant past, a stylist and hair-stylist. King of Normcore. Friend of Young People. A Russian designer who is well-known not only in Europe and the USA but also in the Asian and South American countries. The author of four photography books. He became the first Russian designer whose apparel is sold at Dover Street Market and produced with support from Comme des Garçons. Last year he made the Top 500 list of the fashion world’s most influential people by the respected website Business of Fashion. He had not shown his collections in Russia since 2009 ‒ until recently, when he made an exception.

Mid-January 2017 saw Rubchinskiy present a new collection in Kaliningrad: things from his own brand plus clothing created especially for Adidas Football. The collaboration between Rubchinskiy and Adidas is connected with the 2018 FIFA World Cup tournament that will take place in Russia. One of the locations that will be hosting the World Cup matches is Kaliningrad, originally a German city. It is also the first Russian city in seven years to host a presentation of the designer’s collection in his native country. The links between the German brand and the Russian fashion designer are not immediately obvious yet quite logical: the former Königsberg; the double heritage; the fact that footballers of the Russian team have been playing in a kit from Adidas at almost every World Cup to date.

For the presentation of his collection, Rubchinskiy had chosen a historical edifice on the bank of the Pregola River ‒ the most Italian of the extant German buildings in the modern-day Kaliningrad. The Königsberg Stock Exchange, an example of Italian Neo-Renaissance with Classicist elements, a style quite atypical for the city, was built between 1870 and 1875 and designed by the Bremen architect Heinrich Müller. During the Soviet era, the Stock Exchange building housed the Sailors’ Palace of Culture; in the noughties, it was renamed the Regional Centre for Culture of the Youth. The content, however, stayed the same: an amateur literary theatre and ‘exemplary ensembles’. Parquet floors and linoleum. Lacklustre velvet and tattered leatherette. A covered gallery with arched windows opening to the river: thick ice through dull net curtains.

And it is in said covered gallery that the collection is presented. One by one or in pairs, Rubchinskiy’s favourite characters take to the parquet: young men ‒ pale; shaven-headed; thin; somewhat slouching and awkward, wearing something baggy, half-sportswear-like, droopy, saggy. Serious faces; no emotions; looking past the camera; hands in pockets. The soundtrack: the recorded stories of selfsame characters. Basically, a short account of who they are: their name; where they are from; what their age is; what they do for living; what their dreams are. Sixteen; fourteen; eighteen; twenty; twenty-two. Maxim; Styopa; Valentin; Artyom; Gera; Emil. Kaliningrad; Moscow; Makhachkala; Novosibirsk; Velikiye Luki; Ufa. To become an FSB colonel and pursue this career for life; to become a musician; to become an artist; to become a decent man. To discover myself; to become successful; to capture your hearts; to see Russians free and happy; to find myself; not to die by the age of twenty-five.

The presentation lasts slightly over ten minutes. By the end of the show, the individual voices merge together into one big hubbub, and you can only forcefully disentangle a few separate words from this mumbling, stuttering, lisping and gutturalizing: ‘I’, ‘dream’, ‘my’, ‘childhood’. The models disappear behind a semi-transparent piece of fabric, a sort of makeshift curtain: for a couple of seconds, the shadows coalesce and move on the white background; then the curtain opens, and all these, figuratively speaking, ‘technicum’ kids spill out into the hall as a single throng; they walk threateningly, as if a full-on neighbourhood gang-on-gang confrontation was about to begin here. Clapping. Sporty chic and post-Soviet destitution. Brutality and fragility. Fashion show as a performance, dealing not so much with matters of synthesis between the German and the Russian elements as with generational problems. A portrait of contemporary youth against the backdrop of Italian Renaissance and a parochial cultural centre.

Fragment of the show in Kaliningrad. via Instagram gosharubchinskiy

In any case, the collection is a mixture of so many things. Athletes and fans; white stripes and Malevich’s bright-coloured Suprematist figures; plaid and monochrome oversized suits and quasi-uniform shirts (light blue and khaki) ‒ of a more form-fitting variety; ushanka-hats, flat caps and colourful berets; Adidas in the usual Latin script and ‘Gosha Rubchinskiy’ and ‘football’ in Cyrillic.

Speaking to a New York Times reporter, the designer said that, at a time when so many weird things happen in politics and certain countries embrace nationalist ideas and move towards isolation, something that can unite people are things like football, music or fashion.

From the January show in Kaliningrad. Photo courtesy of vk.com/rubchinskiy

Surprisingly, the things that Rubchinskiy does (all this post-Soviet aesthetics rooted in countless culturally diverse reminiscences) make equal sense to those who grew up in the late 1990s and those who were born in the early noughties and did not witness the 90s simply because they just did not physically exist yet – to those who wore their siblings’ hand-me-downs and bits and pieces from humanitarian aid second-hand clothes’ shops (therefore, by definition, something ‘foreign-made’, ‘non-Soviet’ ‒ therefore, something fashionable, if only for this reason alone) and shuffled on a sheet of damp corrugated cardboard in a makeshift fitting room of a typical marketplace selling cheap clothes, as well as to those who had no need to do any of these things: every possible kind of clothing was already available. In a manner of speaking, they all outgrew the same track suit, and it does not matter how many stripes it had.

And yet it seems that for Rubchinskiy football or, to be more precise, subjects related to football and the football milieu are just another way of speaking about things that interest him most ‒ about generations of youth, a way of presenting this portrait, of assembling it like a mosaic panel from God knows what rubbish and giving this generation a voice. Which is actually what he has been doing since his debut collection, except the role of the football was played by skateboards back then.

2.

Gosha Rubchinskiy was born in Moscow in 1984. There is little known about his childhood: he grew up somehow; he attended some sort of school; he loved to draw something (his mother took him to an art school). Who was his mother? What was the rest of his family like? What walk of life were they from? In which neighbourhood of the city did they live? None of this information is available. It is not as if these were classified facts of his biography (although it might be the case); it is more like he has not bothered to mention any of this ‒ as if it was not that great a deal. And ‒ yes, it actually is not; what really matters is something else, the year and place of birth: Moscow, 1984. The empire, about to fall apart, is still holding together – just.

Twenty-four years later, in 2008, Rubchinskiy will launch his first collection, which he will name ‘Empire of Evil’ and dedicate to kids born after 1991.

Video from the ‘Empire of Evil’ show

Grey T-shirts; track suit bottoms; ‘tolstovka’ peasant shirts emblazoned with bears, two-headed eagles and automatic rifles; sporty cardigans and black masks with metal spikes passed as ‘comfortable streetwear for teenagers’. The ‘Empire of Evil’ collection was presented at the Spartak stadium in Sokolniki (at the ‘neighbourhood football pitch’, as one of the spectators would describe it on the Vkontakte social network): six hundred people attending an improvised lesson of physical education. The garments were modelled by some scrawny and moody boys: age fourteen and over; unprofessional models ‒ skateboarders and graffiti guys, cropped and not quite.

The curtain may have collapsed but the iron is still there: the flimsy prefabricated garages on the outskirts; rusty sheets of metal and steel armature; bent gymnastics bars on waste grounds; grilles on the windows of apartment block buildings.

Gosha Rubchinskiy

‘Empire of Evil’ was followed by his second collection, ‘We Grow and Develop’, still dedicated to the same kids and featuring elements of the same kind of clothing (track suit trousers; T-shirts; tolstovka shirts plus fine-knit sweaters) but more ascetic: no spikes; instead of bears and eagles, the garments featured images of ‘aglets’ ‒ an alien in the shape of a seraph. The word was invented by Rubchinskiy’s team, and they started to use it to refer to the ‘protagonists’ of their collection: aglets is a portmanteau denoting a mixture of innocence and meekness (basically, a lamb, as in the Lamb of God, Agnus Dei ‒ ‘agnets’) and ugliness. A ‘naglets’ (‘brazen rascal’) without the ‘n’. The word, however, somehow did not catch on ‒ a pity. To all of that, add lettering in Slavic script on the Russian shirts, the T-shirts, the scarves. As for the latter, they could easily pass for football fan accessories, provided they were emblazoned with ‘Spartak’ or ‘Dinamo’ instead of ‘Gosha Rubchinskiy’. The colour scheme was dominated by black, white and grey with touches of piercing turquoise and crimson.

The presentation of ‘We Grow and Develop’ was once again reminiscent of an open lesson of physical education. It was held in the building of a defunct Old Believers’ church building; in the 1950s it used to house the training pitch of the Spartak sports club; in the post-Soviet years, the then Mayor of Moscow Luzhkov had it renovated. Today, it is home to the wrestling and boxing sections. Vaulted ceilings; narrow arched windows; benches; sports mats instead of a catwalk; instead of an altar (but on the very spot where one was supposed to be located) ‒ a huge stand/podium with steps, designed especially for the presentation by the architects of Alexander Brodsky’s bureau.

The models, as it were, shuffle in the doorway; barefooted, one by one, walk out on the mat and, after an unhurried turn and a run-up, jump and scramble up on the podium. To get on the top step, they have to make a physical and mental effort, to demonstrate some strength of spirit, willpower and body. The soundtrack is ‘Wings’ by the Russian band Nautilus Pompilius. The finale of the presentation sees 21 people on the podium steps, some of them higher, some lower. Later Rubchinskiy will examine the photographs from the presentation and notice that everybody sitting on the steps seem to have their faces overexposed. Nothing to do with divine intervention, it is just that the photographer had been shooting against the light.

T-shirt from the Spring/Summer 2010 collection

The Spring/Summer 2010 collection was called ‘Dawn Is Not Far Away’: track suit trousers; tolstovka shirts; shorts; T-shirts. No bears and no saints, just the word ‘Rassvet’ (‘Dawn’) adorned with tongues of flame. The presentation took place at a makeshift gym: the models were swinging on parallel bars, doing push-ups, talking among themselves. Basically, the PE test is passed, the circle has been completed: ‘Dawn Is Not Far Away’ became the concluding collection of the trilogy, joining ‒ it should not be hard to guess ‒ ‘Empire of Evil’ and ‘We Grow and Develop’. It was then that Rubchinskiy also reasserted his interest in the generation and the high expectations from these youngsters.

Taruts (concept, cinematography, interview, editing) and Gosha Rubchinskiy (concept, interview, costumes, editing). Part One.

February 2010 saw the presentation of the new ‘Slave’ collection at the London Fashion Week, with the support of Fashion East, a British organisation helping young talented designers. The role of the protagonist of the collection was played by one of Rubchinskiy’s models, a fourteen-year-old boy named German. The designer shot a short dedicated to the kid’s daily life: the teenager is taking a train; sitting in his room on his sofa; channel-surfing with his remote; answers questions; speaks about his own things: what is new at school; what animals he likes and which ones he doesn’t, and so on. The film was shot with an old VHS-camera and then digitalized. In London, Rubchinskiy’s team recreated German’s original room ‒ almost as if he had been sitting here in his chair all the time. And then just got up and left.

Rubchinskiy spent the summer of 2011 as an artist-in-residence on the New Holland Island (St Petersburg): one of the warehouses temporarily housed a gallery/studio; an open skate park was built next to it. The product of the residency months was a photography book entitled ‘Transformation’ (‘Preobrazheniye’) in which domes, icons and sculptures rhyme with faces and bodies of marginalised youngsters in the street: chips on marble and scratches on skin. In 2012, Rubchinskiy signed a contract with the Comme des Garçons brand, which continues to support the designer to date; the shows are held in London.

From the collection featuring prints by Timur Novikov

During this time, prints by the artist Timur Novikov, as well as Soviet slogans, Russian and Chinese flags and the date 1984 (the designer’s year of birth and the title of Orwell’s book), the designer’s name and a phrase from a prayer all separately appeared on Rubchinskiy’s tolstovka shirts, sweaters and T-shirts. As for the clothing line itself, it did not exhaust itself with sportswear: there are also suits, coats from pieces of multi-coloured faux fur, brutal short tanned sheepskin coats (dublionkas), shorts and waistcoats. As it happens, at some point Rubchinskiy’s ‘swashbuckling’, hard-off and desperate nineties ‒ the sportswear and the ostensibly hand-me-down clothes (passed on by an older brother, the father, a male relative, someone random ‒ ‘I don’t wear this myself but perhaps it may be of some use to you’); the Cyrillic script; the bears; the Soviet pioneer slogans ‒ became export goods. In recent years, albeit still in demand, it is not girls à la russe but the ‘New Russian’ type who has been at the forefront of the European and global fashion scene. Having grown up in the post-perestroika Moscow, the designer has captured the notorious Zeitgeist and is now making sure that all these things that belonged to the underprivileged, the hungry and the angry are now coveted and worn by those who are always ‘happy, full and sure’.

As a rule, the presentation of each collection is supplemented by some other thing – a film or a series of photographs. ‘Transformation’ was followed by three other photography books by Rubchinskiy: ‘Crimea/Children’, ‘Youth Hotel’ and ‘The Day of My Death’.

From the ‘Youth Hotel’ photography book

The first two are dedicated to teenagers living in the post-Soviet space. Contemporary school kids in block-building districts, at sports grounds, amidst the Soviet decor of their parents’ flats, against the background of Soviet mosaic panels, in the street and in city parks. Normal children, all of them different: there are skateboarders; there are serious cadets with posters of the Immortal Regiment patriotic movement; there are students of a maritime college ‒ incidentally, the only uniform featured in recent years: the spirit of a soldier and iron discipline; there are elementary school students kicking a ball around, still in their school uniforms. The whole print run of these two books was sold out in a matter of just a few days. As for the third one, we will deal with it a bit later.

For Rubchinskiy, design and fashion are like an absolute art form that does not limit itself to clothes, merging architecture, photography, video, performance, music and sculpture. Beauty only comes into itself in a specific context for him; the things that matter are: who is wearing this? What is this person saying, what does he feel? How does he move and in what kind of space is he moving? And what does this space surround?

The ‘Sports’ collection (Autumn/Winter 2015)

He implicitly addresses the memory of generations; the nineties: neither the ideology, nor the religion but a lesson of physical education ‒ some sort of jumping and games involving lots of movement going on, and a string with keys to the flat is showing from under the T-shirt, and another one with a Russian Orthodox cross.

His name and surname on the tag of his T-shirt ‒ it is more than just a way of identifying the label; it is also a reference to all these strips of fabric with names that parents used to sew on to the clothes that travelled with the child to a summer camp or even said PE lesson. Petya Petrov; Masha Ivanova; Vanya Kudryashov; Gosha Rubchinskiy.

Autumn/Winter 2016

Gradually, step by step, he is assembling a portrait of the generation. The result is a wild collage in which, incredibly, everything fits together, and at once. Here, Soviet and antique sculptures. Soviet official art and Soviet unofficial one. Weapons and fairy-tale characters. Apollo and a sailor. An automatic rifle and the Bear. ‘Ready for Labour and Defence of the USSR’ and ‘bless and save me’. Rodchenko and Novikov. Karen Shakhnazarov (se his ‘Courier’ film: the same Dad’s trench coat, Adidas track suits, leather waistcoats, skateboardists and the same tender age) and Pier Paolo Pasolini. In fact, the seeming significance of Pasolini for Rubchinskiy is something that deserves a closer look.

3.

Last year saw Rubchinskiy become one of the invited designers at the Pitti Uomo 90 exhibition in Florence where he presented his Spring/Summer 2017 collection. Huge suits worn on a naked body; huge double-breasted bright red jackets/pea coats; wide stonewashed jeans and, again, track suits, this time sporting the logos of the Fila and Kappa brands, a nod to the 1990s yard games: which one are you rooting for ‒ for Fila? Alongside his fashion collection, however, Rubchinskiy presented a short ‘The Day of My Death’, a tribute to Pasolini, made with the actress and director Renata Litvinova, as well as a book under the same title ‒ a print interpretation of the film. The designer told the Vogue Magazine that the collection, the book and the film are all his ways of delivering his message to the viewer. Rubchinskiy says that the body of work of Pier Paolo Pasolini has served as an inspiration for him; according to him, many of this artist’s ideas and his poems perfectly reflect the moment in which we live now.

The presentation was held in an abandoned 1930s tobacco factory in Florence; the action of the film is likewise set in this factory. At home, fashion critics either ignored the film or wrote that, while the idea was distinctly presented, the clothes featured in the footage were not included in the collection. Somebody came to the conclusion that the boy who opened the show was cosplaying Pino Pelosi, that is, the young man who, according to one of the versions, killed the director – a seventeen-year-old ‘aglets’. And that’s it. And yet Rubchinskiy’s tribute to Pasolini is actually a sort of sign of appreciation for the similarity of interests and sincerity of the two.

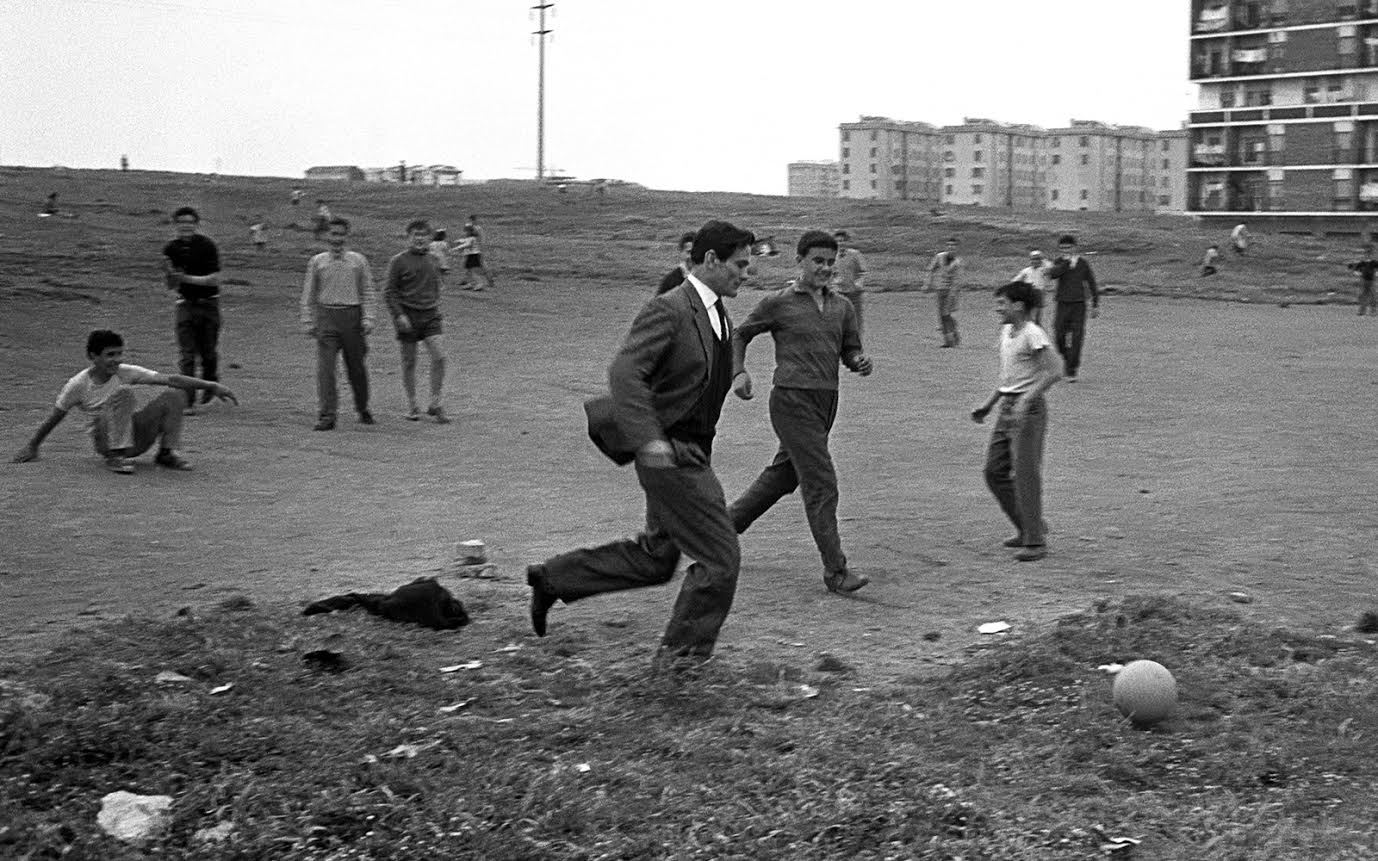

Pier Paolo Pasolini playing football

Pasolini, a former provincial teacher, a romantic poet ‒ broken, confused, comes to Rome, meets the lumpen from the southern suburbs, meets young losers and poor teenagers and falls in love with this underbelly of urban life, studies it and writes about it: a body of poems, the ‘Ragazzi di vita’ novel, other bits and bobs ‒ just text, though; nothing particularly visual.

Rubchinskiy, a native Muscovite, a successful designer, a photographer, part-time director, meets kids from the ‘sleeping districts’, young people born after the collapse of the empire and instead of writing ‒ as per usual ‒ a text as a tribute to them all, dedicates his fashion collection to each one of them. And he makes them the protagonists of his fashion shows, and, as it has been repeatedly said here, he gives them their voice.

The Sports collection (Autumn/Winter 2015). Photo by gosharubchinskiy.com

The difference between Pasolini and Rubchinskiy is more than just their choice of language but also their choice of distance. Pasolini always stood out among this Italian lumpen crowd: a perfectly fitting suit; an ironed shirt; a trench-coat, perhaps a fedora. The children and teenagers are formally dressed almost like Rubchinskiy’s characters: baggy semi-sportswear was held in high esteem in the poor districts of empires. Let us take a look at the photographs: see Pasolini visiting slums; see him play football on a waste ground; see him sit in a Roman suburb against the background of a gas-holder. There is always a strict line between him and the rest of them, even if visually the line is nothing more than the perfect crease in his trousers. As for Rubchinskiy, it is impossible to tell him apart from his characters ‒ not at first glance, not even at a second one. Make them all stand in one line, and he will be exactly the same: the same trousers, the same cardigan, the same cropped hair, with an at least similar background as a teenager. Someone who has probably been beaten up quite a lot. Someone who has probably beaten up others quite a lot.

The Spring/Summer 2017 collection

And it would be nice to think that he is able to quote ‘The Communist Party to Young People’ (‘II PCI ai giovani’): ‘You have the same mean look. / You’re fearful, uncertain, desperate / (alright) but you can also be / bullies, blackmailers and cocksure: / petty-bourgeois prerogatives, friends.’ Or even not like that but just mentally replacing ‘The Italian CP’ with the more familiar ‘nineties’: ‘It’s sad. The polemic against / the nineties was to be done / in the first half / of the past decade. You’re late, sons! / And it doesn’t matter if you weren’t even born then...’ In fact, if he does not quote it, it can always be done for him. Like just now. Particularly in a context were the 1990s have become not only an export fashion merchandise but also a sort of nostalgia ‒ not for films on VHS tapes or clothing items a size larger than you would need but for the energy that was spurting from tiny crack only to run dry eventually.