Fluxus is just beginning

An interview with Jeffrey Perkins and Jessie Stead

10/06/2019

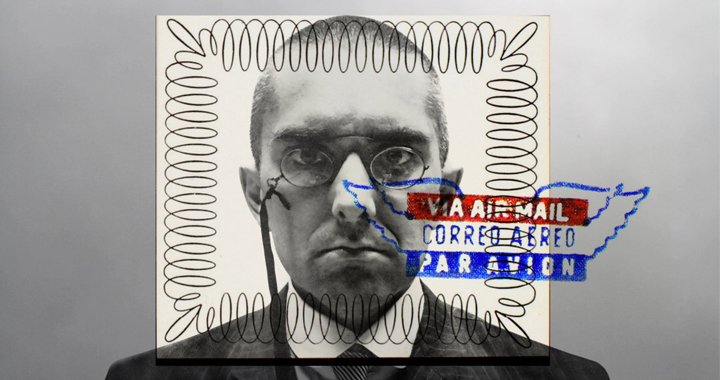

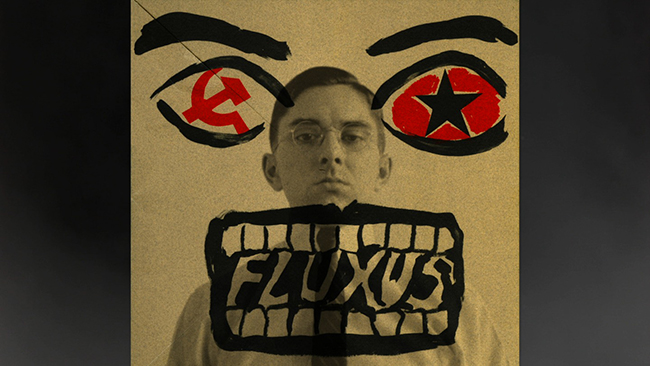

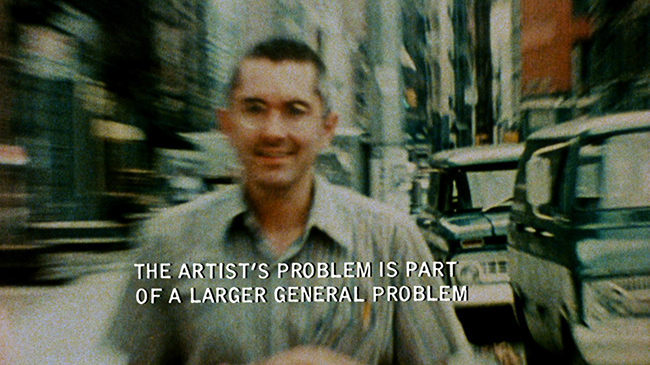

Up until today, George Maciunas, the Lithuanian-born artist, graphic designer, and architect – a man of many trades – had remained an enigmatic and mythic persona behind one of the most radical experimental art movements of the 20th century – FLUXUS. And in all likelihood, things would have stayed that way if another artist, Jeffrey Perkins, hadn’t made a movie about Maciunas.

Described by Nam June Paik as being “the Fluxus underdog,” Perkins – like Maciunas – has taken on many roles. Having worked in relative obscurity for over five decades, in the 1960s he collaborated with (and would remain close with) many Fluxus artists (including Yoko Ono, Alison Knowles, and George Maciunas himself), as well as: co-founded the premier rock and roll concert light show The Single Wing Turquoise Bird; has been associated with Anthology Film Archives in New York since 1986; completed his first feature documentary The Painter Sam Francis in 2008; and worked as a cabbie, having chauffeured most every avant-garde star around New York City – to name just a few of his life’s highlights. Perkins has been best known for light projection performances and his work Movies for the Blind, which was based on sound recordings of interviews with passengers in his taxi. Up until 2009, that is, when he started working on a portrait of the founder and impresario of Fluxus; it was titled George. The story of George Maciunas and Fluxus.

From its conception, George was not meant to rehash the clichés of standard documentary movies about art and artists. Adventurous yet tragic, the life of Maciunas – which was fully dedicated to Fluxus – was far from boring. The movie follows Maciunas’ life path from birth to his untimely death of cancer at the age of 47, including his establishment of Fluxus in 1962, the creation of the first artist co-ops in the New York City neighborhood of SoHo, losing his eye when he was nearly killed by gangsters, and his attempt at establishing a Fluxus colony on a remote island in the Caribbean. Throughout George, the question of “What is Fluxus?” takes on perpetually new dimensions as the subject is explored in discussions with nearly 40 different artists (including Jonas Mekas, Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik) and scholars across the world, along the way revealing the inherent complexity of both Fluxus and Maciunas himself.

In order to bring the intellectual nature of Fluxus into the dynamic form of a film, Perkins hired Jessie Stead (a Brooklyn-based interdisciplinary artist from a younger generation and also known for her band Hairbone, together with Nathan Whipple and Raúl de Nieves), whose spirited and vigorous way of editing, sound design and motion graphics brought a unique dimension to the movie.

After nine years in the making, George. The Story of George Maciunas and Fluxus premiered last February at Doc Fortnight 2018: MoMA’s International Film Festival of Non-fiction Film and Media, where – for the first time in the history of this event – it was awarded the whole week of screenings.

I met Jeffrey Perkins and Jessie Stead shortly before the European premiere of George at Art Basel (15 June 2019) to talk to them about their collaborative process and why Fluxus is so important for contemporary artists working today.

Jeffrey Perkins: I conceived this movie about George Maciunas in 2009, just after I finished my film about the painter Sam Francis. I decided to do this because I needed a job. I knew that there had not been a portrait made of him yet. I felt confident that I could do another film about an artist, and I knew that Maciunas was an unknown star, a secret star in the art world.

Jessie Stead: A lot of people I know who went to art school don’t know who he is. I actually knew of him through Sonic Youth, when I was much younger, which is interesting. They reference him on occasion. I learned here and there about Fluxus and Dada in art school, but I think Maciunas himself has been kind of lost. A lot of people would say, “Fluxus? I don’t really know what that is.”

JP: When I thought of making the film I didn’t see Fluxus so much as performance art. I thought that it had a kind of dry sensibility, and much of what I knew about Fluxus was as an intellectual art in text form. How could that be made dynamic, as a movie? [Addressing JS:] I emphasised to you that the text was very important. What you ended up doing was not particularly focused on text, but your montage is dynamically structured in cinematic layers.

JS: [Addressing JP:] There were about 40 interviews that you had shot around the world and a gigantic collection of images of artworks. As I went through them, I would think, here is an image of an artwork and it’s nice. I can also look it up online, I can look at it in a book, but what a movie can bring to it that other media can’t is movement and a soundtrack. The sound part is easily overlooked but crucial, because a lot of important Fluxus works are audio works. It also encourages an overlaying of different artists’ works mixed together, briefly creating something new. So it’s generative, and this harmonises with Maciunas’s vision, which emphasised networked collaboration and also entertainment. The montages have stylistic differences depending on the scene’s content and the works themselves. The George Brecht scene, for example, is very austere. I think that his work was as well.

JP: There were these dry pictures, which were photographs by Maciunas. An example of how your talent carried the film is the one sequence using the Brecht piece Ball puzzle / Observe the ball rolling uphill, and you animated it.

JS: The piece is an “event score” with a ball bearing, so I simply performed the score. It was fun. There are different dynamics according to the works themselves, and how they could be re-purposed to illuminate biographical points in Maciunas’ life.

JP: That’s a perfect example of collaboration with another artist.

JS: Several artists even. It’s me, you, Brecht, Maciunas. I love that about the film. We are working together, resurrecting the dead.

JP: It felt from the beginning that the film should be a collaborative process, and it was. Besides you, there were other people involved from the very early stage of making George, like Cassidy Petrazzi, and Liz Dautzenberg who lives and works in Amsterdam. And there were several others involved in the various stages and times of the productions, too many to mention here. I researched in three archives in three different parts of the world. That was the palette for the movie, and you invented several things.

JS: And there is music and audio, many of which are original recordings of Fluxus pieces. It is easy to forget that the sound design is constructed from actual Fluxus artworks, some of which are comparable sonically to traditional Foley sound effects. The music soundtrack is also really cool. It includes Sonic Youth – they generously lent some tracks from their album Goodbye Twentieth Century, which consists of seminal avant-garde scores, some of which are Fluxus related.

JP: There is quite a bit of Henry Flynt, Takehisa Kosugi, Yoshi Wada, Ben Patterson, Mieko Shiomi.

JS: Charles Curtis recorded some medieval music specially for George. Maciunas was a big fan of music from that period. There are Maciunas’s own compositions performed by the Apartment House ensemble, and of course Alison Knowles, Joe Jones, as well as some tracks by my contemporaries. Nathan Whipple from my band Hairbone recorded some music. Jack Name, Zach Layton, and Sergei Tcherepnin also lent us tracks, some of which are worked with in layers much like the motion graphics.

JP: To simply show the works would be another dry example of a standard approach to a documentary film about an artist.

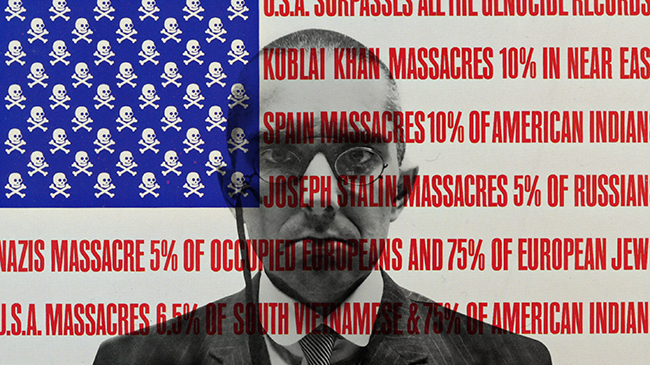

JS: I wanted the discussion topics and the artworks to resonate with each other. There were times when I couldn’t find something in the art archive that worked well, so I looked elsewhere. Maciunas loved Soviet culture, so I looked online at Bolshevik films and used a couple as B-roll in addition to the Fluxus works. That adds another layer. All that stuff was in his head. In the interviews, people talk a lot about how much he loved Soviet revolutionary aesthetics, and cartoons. There is an old Betty Boop cartoon with a chess board, which resonates with Duchamp and John Cage, who significantly influenced Maciunas. I found it online, and it’s easy to imagine Maciunas doing this himself if the internet were around then. He often used magazine cut-outs in his graphic design; sampling from the internet is very similar.

JP: In fact, an important reason for hiring you was your age. And I thought, she will edit this film for her generation.

JS: Or younger than me.

JP: That was an important motivation. I wanted to sell it to a young audience.

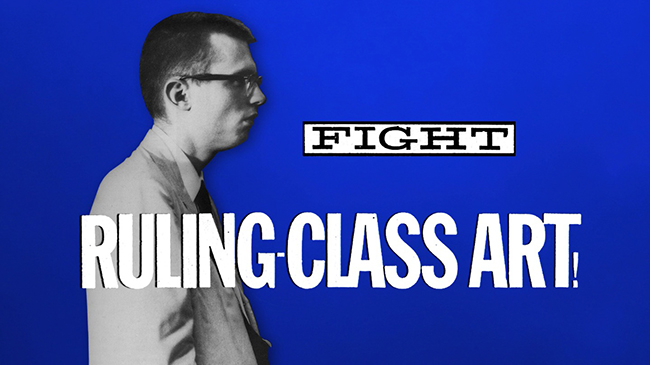

JS: It’s very topical. The discussions of art and politics happening now and Henry Flynt’s critiques of Maciunas’ motivations in the 1960s are one of many points of comparison. And their early protests Communists Must Give Revolutionary Leadership in Culture, and Action Against Cultural Imperialism are especially relevant today and deserve a revisit.

JP: At the early stage of editing, I wasn’t sure if we had enough material. And now when I am watching the movie, the edit is insane. It’s an insane story.

JS: He was insane. A lot of documentaries now are made about people who are still alive. It’s easier to shoot and interview the living. I thought a lot about how we have to bring him back to life, physically, and the challenge of how to do that with only scraps of archival media, very little sync sound. There is Jonas Mekas’ film about George, Zefiro Torna, but very little else is time-based. That’s why we used his audio interviews a lot; his voice is a strong structural element that evokes his presence.

JP: In both of those interviews, the Charles Dreyfus’ and the Seattle radio one, Maciunas lays out the chronology of him in and as Fluxus.

JS: He was preoccupied with art history and wanted to influence Fluxus’s place in it. He describes many art works in detail, but he is also laughing at them all the time. He is very clearly so entertained by it all. I wanted that to be palpable.

JP: It became a driving element in the film, the laughing. It became an inspiration to your editing.

JS: The interesting thing is that only a very small amount of him laughing was recorded, and that’s what is beautiful about it. Compared to today and how audio is recorded near constantly.

JP: Editors are called cobblers, you know?

JS: Really? I didn’t know that. A cobbler, like a shoe fixer?

JP: Exactly. I think it’s a kind of inside slang.

JS: I don’t know. I am not a career editor. I am an artist, and maybe this ties into the film. Was Maciunas an artist or not? The artist as a designer of other artists’ works – is that art? Or, are you not an artist if you work on somebody else’s art? These questions are discussed in the interviews. Some of them say, yes, he was clearly an artist, he made his own work, and others disagree. It gets personal at times. Can an impresario or producer also be an artist? What does that look like? And if not, why? Maybe you can view editing in a similar way. Maybe it’s art sometimes, maybe it’s in the service of art other times and not art. I don’t know. Some people need to codify more than others.

JP: I think art has a special audience. You suggested MoMA’s Doc Fortnight International Festival of Nonfiction Film and Media to premiere the film instead of more mainstream film festivals. So we had a theatrical premiere at MoMA last year.

JS: It made a lot of sense considering you sourced a lot of material from the MoMA archives.

JP: They have the largest Fluxus collection, the Silverman Collection. And now we have the European premiere during the Art Basel art fair in Switzerland in June.

JS: Maciunas would probably roll over in his grave if he knew about that [laughs]. Okay, I take that back, I’m not sure. But it’s very interesting to wonder what he would think about the art fair scene now. It’s totally market driven and the antithesis of his communist-inspired ideals, but he also might have seen it as a networking and branding opportunity, which was also a large part of Fluxus for him. There was such a different landscape then. Marketing, branding, capitalism— artists continue to have paradoxical relationships to these systems today. Art fairs are a global network, which is something else that he really wanted to establish but in the name of a revolutionary, anti-capitalist ideal. So it’s interesting to try and imagine him in this scenario.

JP: I don’t think that if he were alive he could stand himself if he played along with it.

JS: It’s hard to say if he would protest it or not – in the way a young Henry Flynt might. Maybe he would participate – he was very opportunistic. In the 60s and 70s, Maciunas was unique in his milieu to be mixing together art, design, publishing and marketing. Many of his contemporaries were highly skeptical of this, but it is normal now, applauded even.

JP: I remember that when I was trying to raise money for George, I showed a producer the short reel. He thought that the film’s main purpose was as a portrait, the persona of George Maciunas. Because of the dynamic flow of your edit, this is achieved. If you didn’t know anything about him, would you still be interested in the movie?

JS: There are many facets of his life story relatable to any human, and the art is very much interconnected with his life’s significant drama – his poor health, World War II and his family’s displacement. The art flows out of his life events in a specific way. It’s definitely not an insider’s movie. Maciunas himself was fierce in his manifestos encouraging anti-elitism in art. The film will teach you about art. There are early scenes where Maciunas himself explains Fluxus’s predecessors and influences – John Cage, Dada and Duchamp, primarily. His obsessive art historical preoccupations were foundational to Fluxus and are visualized in his chart works.

JP: Part of the definition of Fluxus is that art is basically life itself. Fluxus as a kind of philosophy, I believe, or, it is a philosophical approach to art. Do you think that’s true, by the way?

JS: Jonas Mekas quotes George saying that “Fluxus is not an art movement, but a way of life”, adding that “it has a touch of religion”. Jonas also said “Fluxus is only just beginning”. It’s one of film’s closing statements.

JP: I think Yoshi Wada said that as well, and Ben Patterson.

JS: The film is not only about Maciunas but also an international association of artists. Maciunas’s emphasis on community and anti-individuality is relevant now, or would be in any time. What is the group? The group can be made to symbolise something. He was constructing an ideology for the group that different members had widely varying opinions about. Some of them agreed with it, some didn’t care, some strongly disagreed. I think group identity is very interesting in art. On occasion, I’ve been discouraged by gallerists from collaborating with other artists.

JP: Really?

JS: It happens in some situations. It’s easier to market singular names, the individual genius stereotype. To kind of force the group identity of Fluxus into circulation was maybe how Maciunas in his revolutionary imagination was actively retaliating against the Western art cannon, the dominating “great male” name, I think.

JP: The film was made out of this collective dynamic.

JS: Filmmaking is a multi-faceted balancing act that in itself is a collaboration between images, sounds, and language in addition to a social and professional collaboration. You’re always doing several things at once, like maintaining historical chronology while introducing larger conceptual points. I think The New York Times said that George is “a bit overstuffed, but perhaps by design”. That made a lot of sense – he had an overstuffed life.

JP: There could be another kind of movie about Maciunas; a dramatic film would be interesting. But this documentary sustains itself as art history, an important art film that people will refer to in the future.

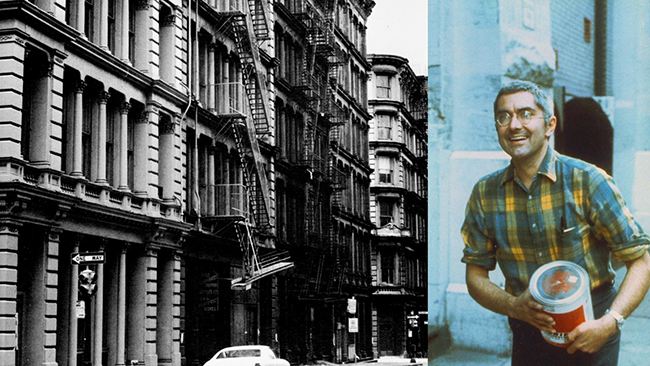

JS: There is a lot of lost history it recovers. Many people in the New York art world don’t seem to know about his unintentional role in the gentrification of Soho – the Flux Houses, for example. It’s an early version of a now-familiar story about complications between artists, real estate and gentrification, which have, of course, accelerated since 1964. The Flux houses were meant to be a group of industrial lofts he envisioned operating as an integrated artist network; the resulting 10-year tumult is spiritedly discussed in the film with many who worked in SoHo alongside George— Yoshi Wada, Milan Knížák, Shigeko Kubota, Ay-O, and Richard Foreman to name a few. Foreman still lives there.

JP: Maciunas had an idea to create a utopian community right in the middle of New York City. Then there’s the Ginger Island story… still, when I watch the film again, I think, wow, who is this person? This is crazy.

JS: It’s not boring. I personally think that George is one of the best movies about art and an artist ever made. I really do. I think it blows away any other documentary I have seen about art and artists. That was our goal and we did it.

Jeffrey Perkins – director / producer

Jessie Stead – edit / sound design / motion graphics

Liz Dautzenberg – production manager / assistant to the director

Cassidy Petrazzi – associate producer / researcher