The struggle against capitulation of the soul

An interview with film director Ilze Burkovska-Jakobsena about the animated film My Favorite War

Norwegian-based film director Ilze Burkovska-Jakobsen's full-length animated film My Favorite War had its world premiere in June, in the French Alps, where it was screened at the Festival international du film d’animation d’Annecy and then won the main prize in the Contrechamp section of the competition.

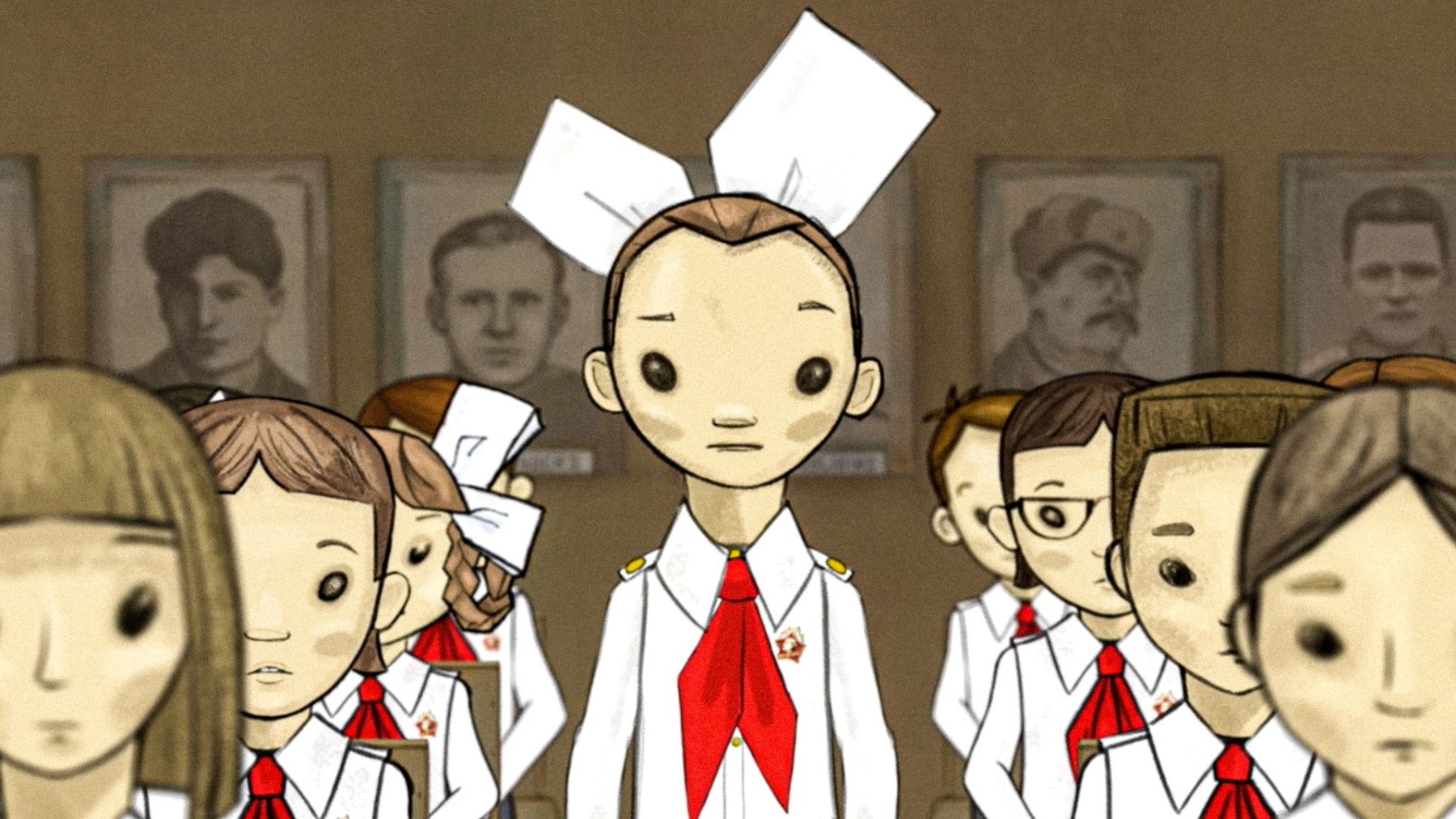

It is a true-to-life story about Latvia based on the director's childhood memories from the 1970s, when the Soviet regime ruled the state, to 1990, when the country regained its independence. The main character in the film is a little girl who grows up in the refuge of a loving family in the Kurzeme region of Latvia, where the presence of the Soviet military can be felt. As she experiences childhood events in all their vivid range of emotions, through the eyes of a child the girl also sees the falsified truths of the Soviet system and the false decorations and propaganda created to reinforce it – until, step by step, she comes to realize the truth.

The director has made this animated film to complete a mission – to tell the world about Latvia. Her filmography includes a number of works that focus on personal stories through which past and present events of Latvia are revealed in a broader context. In the films The Class Photograph (2001) and The Class Photograph, 10 Years Smarter (2011), Burkovska-Jakobsen worked with her former school classmates who, in just the thirty years of their lives, had managed to survive three periods of historical national importance and create lives for themselves after the collapse of the Soviet regime. Similarly the director made the documentary My Mother’s Farm (2008) as a story about the post-WWII generation in Latvia, which was caught up in the twists and turns of political and social upheaval; specifically, how these events affected the life of an ordinary person – the director's own mother.

The film My Favorite War was made as a joint work between Latvia and Norway, in collaboration with the studios Ego Media (Latvia), Tritone studio (Latvia), and Bivrost Film (Norway). The animated characters were created by artist Svein Nyhus, a Norwegian children's book illustrator and writer, whereas the background art of the animated film was created by Latvian painter Laima Puntule.

My Favorite War is an autobiographical-based story about a childhood spent in Soviet Latvia. In a sense, childhood has neither political nor ideological nuances – it is simply childhood. What was your childhood like – from the perspective of a small child and disregarding the historical context? Where was it spent and how?

My mother’s parents lived outside the city of Kuldīga in a house that was next to the forest. I also spent a lot of time there – under the blue, beautiful sky, roaming the meadows, fields, logged areas and forests. I felt free and good. My family was big and busy. My grandparents were always there – both my mother's parents and my father's parents, as well as my father's two grandmothers and grandpa's sister – Herta. Aunty Herta had caught polio, so she was always sedentary. And always in the same place – in our kitchen. We took her everywhere, and in all of Kuldīga, she was the only person known to be in a wheelchair and who would go out in it. My childhood was definitely happy, mainly because so many people loved me. I was cherished and maybe even spoiled. But I was spoiled with love because they also expected me to do chores.

I think my childhood was also very happy because it was very rich. Very rich. I remember driving with grandpa to the watermill where he ground grain. I would lie on the third floor of the mill and watch as the grain flowed down the conveyor belt; I saw how the water wheel was turned by the river; I saw how white and dusty with flower the miller was. All this was experienced in the 1970s –80s.

Growing up in this large family, I absorbed a great deal of experience from the events that took place in the lives of the people close to me. I was in this family when Aunt Silvija died and when grandpa’s cousin Arvīds died. I lived in a dynamic and dramatic environment with anniversaries, coming of age celebrations, silver wedding anniversaries, weddings, and funerals. It was a bit funny when at the RIBOCA2 exhibition, one of the attendants tried to sell me on a video art work by saying that it was created with the aim of stimulating people’s empathy regarding the death of others. I grew up with the awareness that death is here all the time. I have a long and sad story about my very first memory... I remember my mother feeding my little sister Baiba, my mother is looking at me and I feel guilty about having been noisy. I don't know yet that my mother is sad because my sister is seriously ill. My next memory is my sister's funeral. She was born with a heart defect and died at the age of four months. I remember the funeral; I remember how itchy my woolen dress was. A dark brown wool dress. I was only a little over two years old, and yet I realised that this will not be a day when I can whine about something… Mom and Dad are sad, I have a white calla lily in my hands, and we are walking to the little cemetery…

How was this rich childhood coloured by the realities of the Soviet regime? Can one say that this context made the life of a young child less happy?

As for a Soviet childhood, I remember going to pick up my brother from daycare, which was in an old building with narrow corridors; a poster hung on a landing of the stairway – a drawing with some happy children and a quote that was along the lines of ‘Childhood is like a golden apple that shines forever’. And I thought, ‘Come on, stop fibbing! Stop lying! Where is this golden apple?!’ It was clear to me that all this was communist ideology because we had always been taught that we are the happiest children in the world and live in the happiest country in the world. I had already come to dislike this glorification of Soviet childhood at school – that we are happier than other children because we live in a country that protects us, where there is always peace. I realized this duality quite quickly.

What does it mean for a small child to dislike something that is as elusive to them as an ideology? How did you express this?

As an internal deduction that you are being fooled. Not least in the very visual form that surrounds you – there are things that you perceive as true and things that you perceive as false. As a child, I could already sense that not every Soviet poster depicting happy people was true. Something was being forced upon us, something not completely real, an exaggeration of some sort. This can also be said about a person – that they are trying too hard, trying too hard to please; and this transparent layer of wax makes you cautious. And the more they teach you that you have a happy childhood, the more you question that. I remember sitting on the lap of grandpa’s sister, flipping through the pages of the calendar and looking at the pictures of each month... Why is there peace and harmony in the pictures with the summer months, but in October and November, there’s suddenly red flags and illuminated monuments against a dramatically red sky?

What would you like to say now to the little Ilze of that time?

As a child, I didn't learn to ask what I really wanted to ask. I had already intuitively realised that adults respond either quickly and without real thought, or they simply did not want to be candid. Back then, I should have started training myself to ask direct questions so that it would be easier for me to talk to others now.

Do you feel exposed in the movie? Is this a candid story?

Yes, it's a candid story, but only to a certain point. If I made a film just about what, for example, mourning means in my life – all these dear people who have passed, or about what it means in my life to look for happiness or stop being ashamed of myself, then it would be much more exposing. In the case of this film, I constantly place my character in relation to the ideology of the state and the search for human truth. Yes, it's a personal story, but it's not a story about my inner psychological processes, or about how I grew into the person I am right now. I chose to talk only about the ideological context.

In the process of making the film, did you have to compromise on the proportion of historical vs. personal relationships?

It seems that this required the most consideration. It’s not an easy thing to balance because it is so easy to fall into just retelling various situations... For example, how we fought against the building of a metro in Riga, or what the military game ‘Kāve’ was like (which is something no one under 40 will know). There are phenomena that require very detailed explanations, but they must be given quickly and in a way that can be understood by anyone of any generation and anywhere in the world. As I tell these stories, I immediately have to look at what my personal attitude was at the time and how these details affected me back then. The personal aspect must become the guide in this story of history. It’s one thing to leave out some facts, but it’s quite another to weave them together to reflect the whole process that brought us to independence. For a foreign viewer, the occupation – the years 1940, 1941, 1944, 1945 – must be explained at lightning speed and in an interesting way. But it’s nice that in the end, the movie is about choices: that we choose for ourselves whether we define ourselves as happy people or unhappy people. That’s why I think this movie is not just about the past. It is an invitation to figure out today how you will position yourself in the future.

The film was finished by the time the events in Belarus made waves around the world. Has what is happening in Latvia’s neighbouring country at the moment made you reconsider whether any aspect or message of the film could have been created differently?

I must say that in the process of editing the film over many years, I have repeatedly tried to adapt it to the current events of that particular year. Then I realised that the film should be made so that it could also be watched five or ten years from now. On a larger scale, the film is about the search for the truth, and that will always be relevant. The film is still watchable while keeping in mind the events in Belarus, and I hope that democracy will overcome authoritarianism.

In your filmography, themes of Latvian history are explored in the context of personal stories. Why have you chosen this particular approach?

Most of my previous films have come from the desire to tell Norwegians the story of Latvia. Because both The Class Photograph and the film about my mother are portraits of a generation. I created The Class Photograph for Norwegian television with the aim of introducing them to my generation – during its filming we were only thirty years old, but we were already like the revolutionaries of 1905 because we had already lived through three eras – stagnation, a national awakening, and the first wave of capitalism in the 90s. We had already acquired three decades of diverse experiences. My five classmates from the town of Saldus and their life stories made a good fit for that kind of a historical portrait of Latvia, and they allowed me to outline how quickly everything in life can change. At the time, we were portrayed in the West as being pitiable, so my motivation was to let the people speak for themselves, to let them show their own lives. Ten years later, when I created The Class Photograph, 10 Years Smarter, I returned to my classmates. The financial crisis had begun, and this film was more like a portrait of that crisis year. In my opinion, it was also a portrait of the luminosity of Latvia.

You have portrayed quite a few people of the Soviet-era. Can you surmise that they have a common set of personal traits?

What I recognise and define as the ‘Soviet human being’ is exemplified by the word ‘resignation’. The belief that nothing can be changed nor, above all, improved. The ‘Soviet human’ believes that if something is going to change, then only for the worse. They also do not believe that anyone could act altruistically or be guided by an ideal because everything is linked only to self-interest. The ‘Soviet human’ is also a rather severe materialist. Communism raised us to be unpleasant materialists because in the unequal society of that time, any small material privileges that were available would arouse great envy among people. The system was very poisonous to human souls. So many people sought external material symbols, and that was still evident during the financial crisis of the 2000s. Those who felt they had to buy more than they could afford fell into the hole. That is my observation.

On the other hand, I am the completely wrong person to ask about observations. Everything I do is always related to the fact that I have a rebellious nature. If there are any stereotypes, I definitely want to resist them and prove the opposite. I want to prove that there is at least one person, one single person, who is different! I cannot generalise that my whole generation or that of my mother are ‘Soviet humans’. Of course they aren’t. These are people who have fought and resisted; they have always had common sense and an innate sense that life can be improved.

The title My Favorite War is paradoxical and, in a sense, even provocative. How would you explain it?

Life is a struggle. If not quite a war, it is certainly a struggle and filled with constant battles – because situations, events, and laziness persistently pull us into their whirlpools, which are certainly not improvements in the world but rather a slowing down of world improvement. If you won't fight with yourself to become a better person, then you have given up and are dead. You have spiritually capitulated. The Polish television series Four Tank-Men and a Dog is where the term ‘favourite war’ comes from literally, but in a figurative sense, it is one’s inner struggle for having faith in human goodness. No one is perfect – neither myself nor those around me, and least of all the kind of rubbish who seek authoritarian rule.

Speaking of the process of making the film, could you expand on your collaboration with Svein Nyhus, the film's character artist?

Svein Nyhus is a well-known author and illustrator of children's books. In Norway, the well-known animated film director Anita Killi collaborated with him to create the short film Angry Man, about domestic violence. It had great international success; after that, many wanted to work with Svein Nyhus. Svein has an extremely distinct personal style and a strong mode of expression. He has several times been nominated for various prestigious Scandinavian illustrator awards. He was my first choice when I began thinking about this film, but Svein doubted whether he would be a good fit for such a serious story. His wife, Gro Dahle, is also a writer, a well-known author of children's books who does not shy away from difficult topics. Svein’s involvement in my project is mainly due to her convincing him that he should. Svein is extremely enthusiastic and works with great efficiency. Every time I received his sketches it felt like Christmas! Quite unexpectedly, he also had his own visual memories of a time that we both had never experienced. In his youth he had a keen interest in WWII, and he even knew the Polish television series Four Tank-Men and a Dog, as well as the adventure film series More Than Death at Stake.

How were the final decisions made regarding the aesthetics of the film?

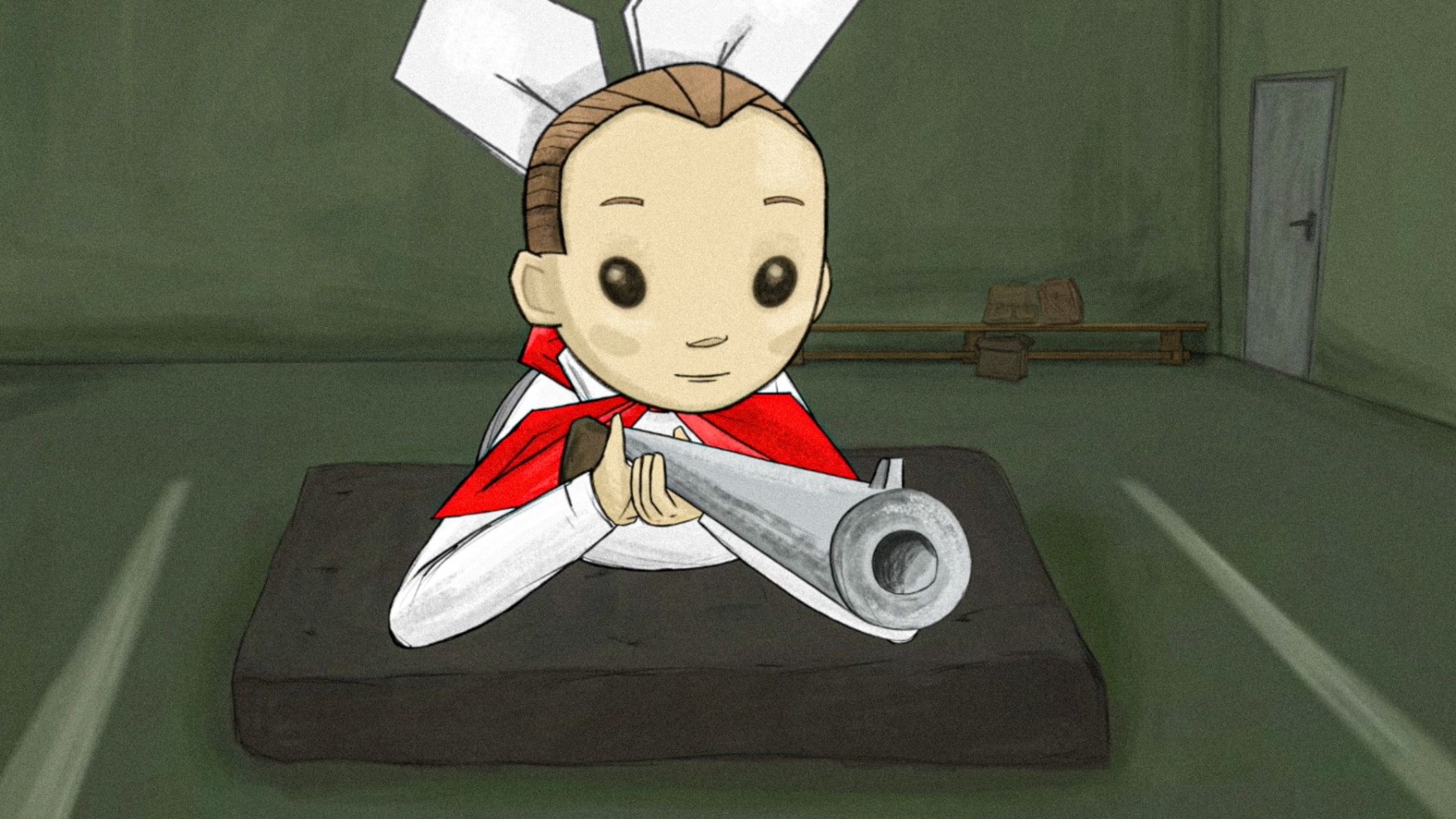

The hardest part is the beginning – when the main character guidelines are adopted. We had a long discussion about, for example, what the outlines should be like – whether they should be in pencil, brushstroke, or charcoal. It was very important for me to keep the kinds of eyes that Svein usually draws. Eyes like that can only be found in our film (and, of course, in the already mentioned short film Angry Man). Our characters do not have pupils, just big black blotches. Consequently, the animators here in Riga had their work cut out for them because if there are no pupils, the rest of the face has to be put into motion. I encourage people to see the film and acknowledge how different these characters are compared to the rest of the world of animation.

What was it about these black blotches for eyes that intrigued you?

I held on to these eyes mainly because I wanted the film to get across the slightly scary feeling of those times. And Svein, in general, is able to perfectly combine the childish with the slightly scary. His characters can exhibit both naive happiness and the suspicious. It’s what we talked about earlier – that a child has a sense of what is true and what is not. Yes, maybe a little kid is not yet able to define what he believes and does not believe, but we have created characters that have visibly disparate ways of looking at things.

You also collaborated with the painter Laima Puntule.

Yes, another important artist on our team is Laima Puntule, the background artist. There are about fifty animated scenes in the film. Laima interpreted Svein's sketches. He created sketches for the shelves, the TV, room interiors, etc., while Laima replicated them from different angles and adapted them by adding more precise details of the era.

In terms of details (clothes, household items, etc.), do we see objects from your childhood in the film? Things you actually owned?

Yes, very specific ones – a shirt from my teenage years that was drawn and animated in the film. I wore it down till it was a rag. I had the porcelain cup from the Riga Porcelain Factory until last autumn, when I sold it in Norway – as part of the film’s co-financing campaign. My Pioneer uniform too, which, as a kind of weird memory, I had been lugging around the world until the same autumn of last year. I hadn't saved the scarf, nor any of the badges, but pictures of them can easily be found on the internet. A lot of things and details in the film are very specific, and it gives the film authenticity and a legitimate documentary aspect.

Was the choice to work with Latvian animators a forgone conclusion?

There was never any doubt. If only for the reason that this is a documentary story. Despite the fact that the animators are younger than me and may not have experienced the specific period of time portrayed in the film, they still have a very organic sense of the environment as well as of the characters and objects. I was lucky that almost all of them were connected to the rural way of life in some way and knew what hay and cows were. In addition, each country has its own specificity of how things look visually. For example, in Latvia haystacks are stacked vertically, whereas in Norway they are low and long.

What kind of technical tools did the animation teams use?

The first scene was partly drawn by hand because it has several quite complex angles, and we wanted to create a very, very warm opening scene. It was created together with Inga Tabaka. The rest of the animation is 2D cutout and partly 3D. The 3D objects are snow, rain, a river, boiling water, as well as a tractor, a plane, a backhoe – various moving things that are difficult to animate.

There have always been talented animators in Latvia, and their names are increasingly being heard in the world.

There’s a professional environment here that is powerful and can take on a large capacity of work. I can name all my animators – they have done a great job. Nils Hammers worked with 3D, Krišjānis Ābols drew many of the characters and complex animated scenes, as did Harijs Grundmanis. Kerija Arne animated the crowd scenes – she faced a real struggle with the Pioneers and war veterans. Arnis Zemītis can wonderfully express emotions and he worked on the close-ups. Toms Burāns is able to create visually impressive things; he had a difficult job in working with close-ups, and he was also in charge of the sepia-coloured war scenes.

How did work on the film’s music and soundtrack go?

Composer Kārlis Auzāns has been, as they say, my ‘partner in crime’ from the very beginning. He created the first melodies nine years ago, when we had just started working on the film, because when presenting the project, in addition to Svein’s drawings we also needed a theme for the film. Kārlis composes wonderful themes, but, of course, authentic songs from that era were also needed. Kārlis could also write the music for orchestra and choir so that they would sound militaristic, but today, both the instruments and people are different. Honestly, in today's Latvia, I would not want to cause people the fear and pathos, nor the horrors and conviction, that sets in when one hears the Red Army Choir sing. When we hear them sing, we understand that the choir is standing on the Kremlin stars – balancing between hell and the infinity of the Orthodox Church. That’s why we had to buy these archival recordings. Everything that I wanted in order to make it sound like the ubiquitous Soviet ideological ‘buzz’ had to be bought. Another thing is the brilliant sound work: searching for the right sound effects and working with sound director Ernests Ansons. Can you imagine the the sound director's favourite place is the refrigerator! – building the refrigerator’s room, building its door, going inside it and listening to how it opens and closes.

What kind of feelings would you like the audience to experience with this film?

I would like people to leave the cinema with the idea that life is beautiful. There are some movies that I watch on the big screen, and to make it a complete cinema experience, on the way home I invite my husband to have a glass of champagne with me. In honour of the beautiful film and life. Two weeks ago I was in Switzerland, where our film was shown during the festival. I received a message from acquaintances that they, too, were so moved by my film that afterward they went to a restaurant to drink champagne. It is a huge compliment when you have provided someone with that moment and experience in which you feel that life is worth living.

I assume you had the opportunity to see part of the Annecy Film Festival programme. What new trends in today's animation did this edition of the festival bring to the fore?

In our category, feature films had very varied visual solutions – each film had a completely different style. The Polish film Kill It and Leave This Town completely transported me to 1960s Poland, and although some thought that it was too dogmatic, it seemed to me that the film was about how we age. It is the director's version of his parents; it’s also an autobiographical story, but not as specific as mine, which has specific years and numbers. Many have asked me about the movie True North, which tells the story of a North Korean concentration camp. Its content is weighty, all of the characters are in 3D, and stylistically it could be described as a distinctly Japanese attempt to create a documentary story. I thought that it would win, but apparently the 3D didn't work on the jury as well as our ‘chalky’ animation did.

What happens now after winning at the festival? What is the next step for the film?

Immediately after Annecy, the Ottawa International Animation Film Festival, North America's largest animation festival, announced itself. We’re also planning to participate in both major Asian animation festivals. In total, the film is currently planned to be screened at 17 festivals, including both documentary and animated film festivals.

However, I was really looking forward to the premiere in Riga. With that I could finally shut the book on this work. It is a celebration for the group and the creators. It is a team effort and it should be acknowledged as containing the contributions of many people.