I like the questioning man…

Stage director Kirill Serebrennikov on the reality as theatre and the theatre as reality

For this conversation with Kirill Serebrennikov about the theatre and challenges of the times we first headed to Ovcharenko Gallery, where Nestor Engelke’s exhibition ‘Pavilion for Clumsy Reading’ was in the final days of its run. The artist hacks portraits of Russian classic authors out of wood with an axe, discarding anything superfluous and preserving everything that must be preserved as something ‘written with a pen’ (as in ‘What is written with a pen cannot be hacked away with an axe’, a Russian proverb) or, in other words, is part of the prototypes of Russian literature. At the sight of the likeness of Gogol, Serebrennikov exclaimed: ‘This Nikolai Vasilievich simply has to become the talisman of the Gogol Centre!’ No explanations were necessary for me to understand why. The portrait is an exceptional embodiment of the idea of Romanticism today. It is a Romanticism that has gone through the hell and horrors of the Second World War, fuelled the practice of the artists of the post-war art brut and the CoBrA group… And yet it has not disappeared, it has not given up searching for the greatness of the living human soul in the very heart of grief and suffering. Yes, if you take a closer look at Engelke’s portrait of Gogol, behind all the trashiness and the chthonicity, there is a great integrity, life and compassion to it. It is not inferior to the 19th-century originals, as far as its powerful emotionality and complexity are concerned.

The same goes for Serebrennikov’s theatre. Convulsions, violence and sarcasm as torn flesh (which is the literal translation of the word from Greek) define the image of many of his productions, including, of course, some stage versions of Russian literary classics. There is no irreverence, deliberately outrageous self-affirmation or debasement in it. It’s just that this is what the world is like today. You have to choose: either you speak about the ultimate thresholds of pain and depth of suffering, or keep your silence… Honestly and without any concessions, Serebrennikov’s theatre bears witness to the wounds and disfigurements of the world without mutating into cynicism and savagery of the soul, remaining faithful to the great mission of humanism, remaining in love with the human.

Work of Nestor Engelke

In conversations, Kirill Serebrennikov speaks of his love for the culture of his country, its language and people. In his stage productions, on the other hand, he tries to liberate them from the superficial gloss imposed by the canon and the overworked image reproduced on stage. I would give a lot to know when he is finally going to tackle the opuses of Dostoyevsky, Chekhov or Tolstoy. However, the question remains unanswered for the time being. He is only searching for a connection with these greats as yet. Meanwhile, this is the list of those with whom the connection has been established: Gogol, Pushkin, Goncharov, Nekrasov, Ostrovsky… The director’s stage versions prove that these classic authors can be passionate, lively, witty and honest conversation partners for the 21st century.

Serebrennikov’s own life is too similar, too dangerously similar to the life of the Genius as described in Romantic literature. A textbook example, really: the free-spirited noble hero confronts the inertia and vileness of the world. As a result of this confrontation, the hero is persecuted by the powers that be and acquires the status of an outcast, a renegade. This similarity is more of a matter of sadness than of pride. We do not specifically focus on it in our conversation, rather preferring another feature of the Romantic culture. This is how the famous philologist and Germanist Viktor Zhmurinsky describes it: ‘Romanticism is a distinctive form of a developed mystical consciousness.’ In today’s terms, it is the way to a new ultimate unity, a synaesthesia of all forms of creativity in the name of a universal assembly of a meaningful world.

The theatre today must respond to new global challenges. On the one hand, social activism (events in Russia, America, Belarus) is transforming into a real performance featuring sophisticated staging of protest movements, solidarity, interaction, street performances, etc. You will never find a suspense of this magnitude in the sublimated aesthetics of entertainment for money. On the other hand, the Covid-19 pandemic is turning a visit to the theatre into an actual health- or even life-threatening undertaking. Is the theatre ‒ and the rest of the arts ‒ ready to respond to these challenges?

There is a third question, one that emerged even before the Covid-19 pandemic, even before the protest movements. It is a radical way of looking at a problem that has been around for some time now: what exactly is the theatre today? What kind of strange business is it? Do we really need to go somewhere in the evening, put on our festive garments just to sit staring at an elevated stage where some weird people are saying all sorts of weird things? The general answers to the effect that by living through someone else’s experience, identifying with a character, we heal our own ailments and study our own neuroses, are no longer sufficient. Suddenly the whole mechanism has stopped functioning ‒ is it because man, living in this new informational field, being part of this global network, has changed a lot? There is this excellent film on Netflix about it, ‘Social Dilemma’. The algorithm that serves as the foundation for any social network is practically uncontrollable; at some point it just gets out of control. The behavioural patterns of humanity are changing. Does all of this have an impact on the theatre? Of course it does. Because the theatre is a human derivative. The theatre, of course, is unnatural, just like any other simulation of existence. In theatre we try to imitate being with some extremely primitive means. The director-demiurge presents his own concept of the world or even the Universe. At this point, a very urgent question arises: do we even need these worlds? Should we go on creating them? Perhaps the human world is already overloaded with pictures, phrases, words, meanings. Perhaps we should fall silent now and find a form for muteness and emptiness… Emptiness as the ultimate concentration of meaning. How do you create this emptiness? That’s a question… The most important thing in this respect is responsibility in front of the viewer, the conversation partner who we address with this muteness and emptiness. Although, as we all realize, spectators often turn to theatre for ‘design’ and some ‘easy-watching entertainment’.

I assume that, considering the challenges of the times, designing existence and doing easy-watching entertainment is unethical. In this sense, the theatre should feel the nerve, the pulse of life. Like you do at the Gogol Centre, responding to a whole range of topical issues ‒ from the overwhelmed human race that has collectively fallen ill (‘The Petrovs In and Around the Flu’) to studies of the Homo Sovieticus and current manifestations of its hellish nature: moral sadism, grovelling, cowardice and thirst for power (projected on the events in Belarus in the ‘Red Cross’ by Sasha Filipenko)…

No-one, of course, predicted the Covid-19 pandemic when we started working on ‘The Petrovs’ Flu’; no-one foresaw the Belarusian protests at the time when we were rehearsing the play based on the novel by Sasha Filipenko… Does a theatre director have to be a visionary? Not necessarily…

But surely a visionary is not someone who naively believes in mystical coincidences! It is someone who collects the codes of life, of being – the ones that will stay universal throughout the times. People like Leonardo, Pushkin, Mahler or Prince Vladimir Fyodorovich Odoyevsky who is the subject of an upcoming Gogol Centre production and a festival…

Yes, the codes of existence are universal. Combined in a certain fashion, they make it possible to project your own experience on what is going on, to restore the link between times. People want to find the meaning of their own existence. And that, by the way, is exactly where all the conspiration theories stem from, this search for some kind of selfish causal link that connects everything with everything. Conspirology is an attempt to build a coordinate system operated by some kind of absolute will. Because we are all scared of chance. Art tries to explain these causalities using its own ‒ different ‒ methods, to produce its own laws of existence of the world. I once tried to get a very wise man who is currently working on a huge book about liberalism to define this concept for me. And he said: nationalists think that people of a single nation should be happy. The leftists want only the poor to be happy. Liberalism means wishing happiness to all the people living in the world. Now this is a formula, this is a code. The theatre is all about liberalism, because it is all about man. It is about man, for man, from man and at the expense of man… And that’s regardless of this feeling we have that it should be based on totalitarian-authoritarian principles that say that everything is ruled by the director’s will. I believe that the theatre of authoritarian will has been deteriorating to a greater extent than other types of theatre. My prediction is that it will fall before long. Authoritarianism presumes unconditional obedience in the theatre, analogous to the army. There is no place for visionaries in the army. And there is no place in the 21st century for the authoritarian theatre. I have no interest in people who just stupidly carry out someone else’s decisions. I like the questioning man, the inquiring man…

Interestingly, in contemporary art the hegemony of man has been adjusted by the post-humanist subjects. The artists focus on the aftermath of Anthropocene when man, due to his own behaviour that has brought about an ecological crisis, has been displaced as the centre of the planet ‒ or even disappeared. Colonies of bacteria, the life of hybrid ‒ organic and non-organic ‒ beings are now taking centre stage in art. Does the theatre even attempt to broach these subjects?

We still look at crystals and bacteria through human eyes. Which means that talking about man getting displaced is just somewhat disingenuous. But let’s talk about Odoyevsky whom you mentioned. A tiny town inside a snuffbox. A boy travelling to an abyss of inanimate matter, of machinery. The child is asking questions: ‘What is the cause of the world, where is its primordial spring?’ A child’s take on the being, on matter ‒ that is what the theatre is about. Or to be more precise, the theatre ‒ it is an answer to a child’s questions.

There have been some quite successful attempts in the theatre to stage plays without human actors. The director Heiner Goebbels mounted a theatre production featuring just machines: they suffered, they glowed, interacted… Some of the machines were villains, others produced in us feelings of compassion. After the performance, people in the public stood up and applauded the machines while the machines took a curtain call and bowed. The whole production was about the absence of the artist on the stage. And yet it was produced by man and performed for man, not for machines. Man cannot be deducted from this kind of theatre.

What I am more interested today is not the subject of the human absence or presence but of setting up a different protocol for communication with the spectators. Should they be sitting in the auditorium, passively consuming the show? Or could the customary ritual be broken and the spectator could become part of the action, modelling the text of the performance on their own? You get up from your velvet seat, pick up your earbuds, your VR glasses and transport yourself to another reality… In the post-information age, man has learnt to combine the incompatible in his consciousness, be an active participant of the meaning-formation process.

In this kind of theatre and hybrid spaces, the viewer becomes a co-author, co-creator of the action. So in certain cases the viewer can be substituted for the director and the actor?

Yes. We have a production entitled ‘Questioning / Who Are you?’ running at the Gogol Centre. No actors take part in it. It is a session of psychoanalysis. People write down their questions and exchange answers with other spectators sitting next to them, with persons they have never met before. And they come out of it completely stunned. They discover emotions and meanings inside themselves that are in no way inferior but sometimes surpass traditional theatre performances and shows.

A view from the performance ‘Questioning / Who Are you?’

What attracts you in ballet and opera direction?

It is an attempt to get to know other media. Surely you will agree that ballet is an incredibly strange spectacle. People dressed in special super-tight clothes moving to music. Pure surrealism. And you must use these means of expression to tell some kind of story. It is truly a childishly naïve task. It is almost like you have been given your granny’s old toy from the attic, and now you are twisting and examining it with great excitement. It is a miracle. Huge wealthy theatres with incredible possibilities, with mind-blowingly well-trained people who literally fly in the air, levitate… It is all the traditional machinery that has been preserved practically unchanged since the times of Pietro Gonzaga and the theatre of the Romantic era. All gilt and velvet. And you have to create something amidst it all… It is a genuine childlike happiness.

Why is it that we can only talk about director of a dramatic or musical theatre as a real profession since the 20th century?

Because it was only then that directors stopped merely setting up mise en scènes and started creating a philosophy of the theatre. Started making Art. Today, you cannot be a theatre director without being a universally trained person, meaning psychology, art history, architecture, rules of composition, philosophy and many other things… I started learning the craft of theatre direction with studies of philosophical texts. And one of the first books that motivated me as a director was by the German mystic and alchemist of the Baroque era Jakob Böhme ‒ ‘Aurora or The Rising of Dawn’. This book describes the demiurgic impulse of man. The world is described as a congruous alchemical system. There is space both for scientific knowledge and mysticism in it.

A view from the performance ‘Baroque’

It is very symbolic that Jakob Böhme has made an appearance in our conversation. The era of narrow specialization among the masters of arts has come to an end. Once again centre stage is taken by the universal world-knowledge celebrated by Böhme, where chemistry cannot be separated from alchemy and craft ‒ from philosophy. It is exactly this kind of universal approach to life’s problems is embodied by the Gogol Centre production of ‘Baroque’. Transparency of all forms of knowledge and art…

Any good project today must possess the quality defined by Wagner as Gesamtkunstwerk: it is a synthesis of arts; it should comprise all the elements, all kinds of knowledge about the world, the ultimate concentration of ideas and meanings. It can be born as a product of the reason or of intuition ‒ as an enlightenment. Because it is not important HOW beauty is born. Sometimes it is born of love but sometimes ‒ of pain and nightmares. I intentionally use this old-fashioned word, ‘beauty’. I just like it. By the way, speaking of baroque (originally ‒ a pearl of imperfect shape) ‒ it is interesting to remember how a pearl is born. A grain of sand ends up inside a shell. And the [inhabitant of the] shell tries to force this grain of sand out like an alien body. It covers it with layers of nacre, mother-of-pearl. To us, a pearl means beauty, but for the [mollusc inside the] shell it is a trauma and a tumour. And so pain and beauty co-exist, and nature’s mistake becomes the cause of beauty.

Is the right to make a mistake an important stimulating factor for a director?

Mistakes are life. There are no absolutely correct, symmetric forms in nature. Symmetry ‒ it is the world of death. Life evolves and progresses thanks to mistakes, thanks to lunatics. A director should deliberately make mistakes in his work. They can lead to discoveries in art.

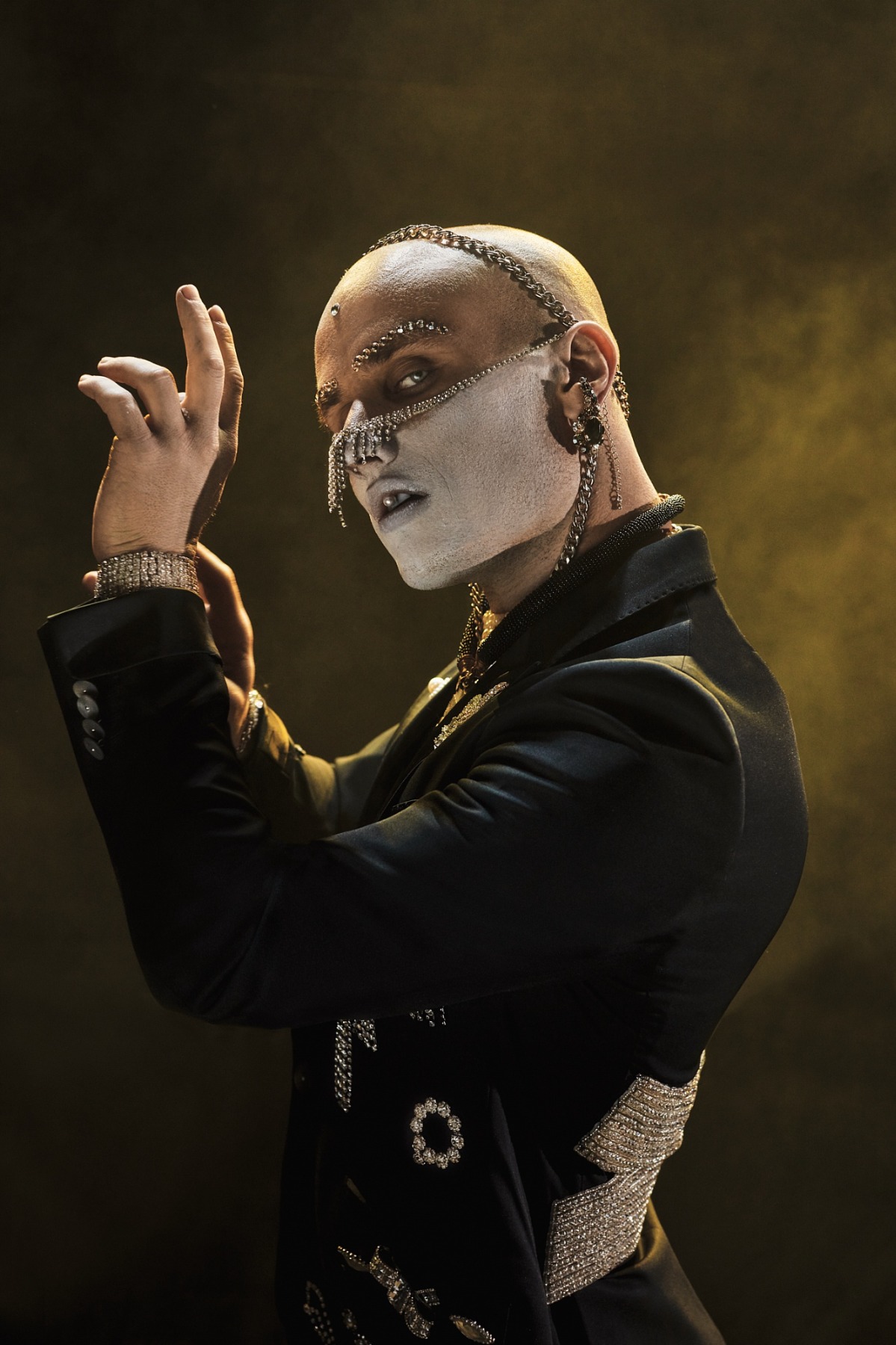

Kirill Serebrennikov. Photo: Ира Полярная

One of these people who reserved the right to make mistakes and were condescendingly viewed as weirdos, as walking mistakes by their contemporaries, was the so-called ‘Russian Faust’, Prince Vladimir Fyodorovich Odoyevsky. Odoyevsky’s ‘mistakes’ in every area of life. from music to electricity, from literature to culinary arts, eventually turned out to be prophetic regarding the paths of civilisation, even the psychological type of the modern-day human. Odoyevsky could very well be described as a visionary. The next new production by the Gogol Centre is a play dedicated to this man. The production will be part of a festival that is being mounted in association with artists and researchers. Who and what is Odoyevsky for you?

Odoyevsky is almost a ‘21st-century man’, hungry for knowledge, curious and always searching. The 20th-century Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset wrote a piece entitled ‘On Viewpoint in the Arts’ (‘Sobre el punto de vista en las artes’). In this text he wrote about the ways in which art explores matter. The eye enters deeper and deeper inside the molecules and atoms of matter; it wants to see the pixels of the world. Odoyevsky was a man who suddenly started thinking about the nature of matter. He was a chemical scientist, a physicist, an alchemist, experimenting with what is referred today as ‘molecular gastronomy’. In this desire to understand the nature of the universe in all the detail, on an atomic level, I see the kind of mindset to which the new theatre is striving in its ideal version. Although sometimes it can also be interpreted as the consciousness of a child who wants to break a toy or even a living being to understand ‘how the whole thing works’. A child’s consciousness is cruel. Contemporary theatre also is a cruel thing.