“Two Is One”

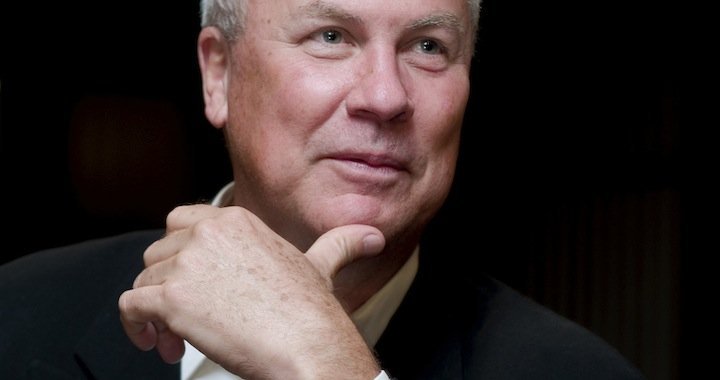

An interview with the American master of the avant-garde, director Robert Wilson

16/04/2013

“It's not 'one plus one is two', but rather, 'two is one',” says the American master of the avant-garde, director Robert Wilson; he continues to explain this reasoning by telling me of his meeting with the German film-legend, Marlena Dietrich, in the early 1970s, in Paris. “I was twenty-seven, she was seventy one, and we were having dinner together. A man came up to our table and said: 'Ms. Dietrich, when you act, you are so cold.' And she replied: 'But you're not hearing my voice. Difficulties arise, in joining the voice to the face.' She can be ice-cold in her movements, but the voice can be very hot. And that was her strength.”

In Robert Wilson's theatre productions, time flows radically slower than in any other play. But he won't agree if you call him a “decelerator of time”. “I don't use 'slow-motion' in my works; it is real time. In most theater productions, time is usually sped up, but I use real time. The time that is needed for the sun to set, or for a cloud to change, or for the day to start. I give the audience time for contemplation, for meditating on other things rather than those that are happening on stage; I give them time and space in which to think.”

After having seen Robert Wilson's almost-eight-hour long opera of silence, “Deafman Glance”, in the Paris summer of 1971, the French surrealist poet and writer, Louis Aragon, published a letter to his deceased friend, André Breton, in the magazine Les Lettres françaises – “we have experienced the future”. With this, Wilson was added onto the list of those continuing on with surrealism. “A dreamer's journey to his heart,” is how the French actress, Isabelle Huppert, describes Wilson's productions.

Robert Wilson/CocoRosie. Peter Pan by James Matthew Barrie. © Fotos von Lucie Jansch

This director also has great talent in human relations – bringing together people who, without Wilson, wouldn't have otherwise met at the same event. He doesn't discriminate by race, intellect, or financial standing, and breaks down these dividing walls of the real world. He stopped a policeman who was beating a deaf-mute boy on the street, and ended up adopting the boy and creating theatre productions with him. In selling tickets for “Einstien on the Beach” at the Metropolitan Opera, he seated patrons who could afford $2,000 tickets next to those who had $2 tickets. Wilson's creative laboratory on Long Island, NY, The Watermill Center, is a place where architects, musicians, actors, writers, designers, film directors and painters from all over the world can combine their diverse knowledge, talents and human experiences to create cooperative projects. As ever, Wilson strongly believes that art can help both people and the world at large: “I passionately believe in art!”

This spring, Robert Wilson, together with the American sisters Sierra and Bianca Casadie (also known as the group “CocoRosie”), will perform a play about Peter Pan in Berlin's “Berliner Ensemble” theatre. About a boy who never grew up, the production is set to open 17 April.

During a break between rehearsals, and while doing sketches for the show's marquee, Wilson spared some time for an interview.

English writer James M. Barrie's story, “Peter Pan”, begins with the following sentences: “All children, except one, grow up. They soon know that they will grow up, and the way Wendy knew was this. One day, when she was two years old, she was playing in a garden, and she plucked another flower and ran with it to her mother. I suppose she must have looked rather delightful, for Mrs. Darling put her hand to her heart and cried, “Oh, why can't you remain like this forever!” This was all that passed between them on the subject, but henceforth, Wendy knew that she must grow up.”

Mister Wilson, what was your way? How did you find out that you have to grow up?

I don't know. I didn't think about it. I was always very anxious about how I would make it in the real world. Because when I was in school, I didn't do anything well. I was not a very good student. You know, I mean, I couldn't imagine what I would ever do. (Laughs) So. It happened by accident that I worked in the theatre. I didn't study theatre. It just happened.

I don't know if I went through that because I was always pretty much in my own world. I was someone who came home from school, and then I liked to go into my room, lock the door and not see anyone. And it was…

The theatre was a way of going into another world, and living in that world, and it was not necessary to deal with the everyday world. I don't think I went through the changes that most people do, going from childhood to adulthood. Baudelaire said: “Genius is childhood, recovered at will”.

You worked in your early years with children – with whom other adults had huge communication problems. What was the key to getting into their world? And how does a child's view of the world differ from that of an adult?

My first play was written with a deaf boy, Raymond Andrews, who had never been to school, and I was interested in how he saw the world. He had never been at school; he didn't know any words; he was deaf.

And then I understood what was going on in him; it was visual signs and signals, and that is how I came to learn a language from him. I began to realize that he knew things that I didn't know. We were not in the same situation because he was looking at things in a different way than I was. Because I was preoccupied with what I was hearing. So, I was just fascinated by him.

And Christopher Knowles, who came to live with me, was an autistic boy. He had been in a school for brain-damaged children, but he was preoccupied with mathematics and geometry, and making languages that dealt more with… His thoughts were organized mathematically. And I was very fascinated by his language and I began to learn it. He said things, like “hadapa that hadapa that hadapapa at at at at”… And I began to learn it.

And what was going on in institutions is, they were trying to correct them; they were trying to stop it. And I just encouraged him to do more. And I began to learn it.

Robert Wilson/CocoRosie. Peter Pan by James Matthew Barrie. © Fotos von Lucie Jansch

How does this world of visual signals, which differs from the world in which people use words, work?

Well, I mean, Chris was using words, but he was using them in a different way. That was what fascinated – what I think that fascinates me – about making art. It's a music. Composers write music as themes and as variations. So, you make a code of sounds, and you can change them, you can destroy them, make a new code, add a deconstructed part, and you can make a dance and you can establish a pattern, you can add a variation of this pattern. You can build time-space constructions on theme and variation. So, the languages of theatre, dance, music and visual arts have a different kind of freedom than this language in which we speak everyday at school; which has laws that are not to been broken, and it has to follows logic and certain rules.

It was more interesting to me in the terms of an artist: what they are doing, how they are constructing their thoughts.

You are making “Peter Pan” for Berlin, for a city in which the theatrical scene has a very intellectual base. Do you believe in the dominance of intellect in the theatre?

Well, they do things for a reason. It's based on a reasoning. And my theatre is not based on that. I don't want to know what it is that I am doing. If you know what it is that you are doing, then don't do it. The reason I work is to ask what it is. But the German education really goes back to the Greeks; they start with classes, and then they get up and do something because of some reason. But I don't think that way.

At the same time, German theatre is not only Heiner Müller, but Pina Bausch as well. She was concerned with emotions, and strongly believed that it is possible to recreate them once more – on the stage and in the audience. But still, German theatre does believe, very strongly, in precisely the words. In your theatre, there aren't that many words. Why is that?

Usually, the words expressed the intellectual side of person. Music is a spiritual side. My work is closer to ancient aesthetics, or to John Cage, where the whole thing is something that has to be heard and it is a kind of music. And the sound of the word is as important as anything else; and if you actually decode a word, if you would break it down, it is like a rock – and when decunstructed, it is full of many many many emotions, and fractions of seconds certainly exist, so the emotions there…

(At this point, a bird flies in through the open window. It lights upon the windowsill and sings.)

Oh, Godhead. (Laughs) It's a little bird. He comes every night at the same hour and sings this little song. It's unbelievable. Every night. I don't know why. And then he goes away. He just comes and does this little song, and the flies away.

(The little bird flies away.)

Susan Sontag said in an interview that she has the impression that you don't really read the text – the plays.

(Wilson laughs very sincerely.)

Well… I can't talk because of the laughing... Sometimes I read the plays.

So, how is it with Peter Pan? People all over the world know the story. I ask because I have the impression that you don't start with words. Could you tell me more about your approach?

Well, first, I always stage a work silently. I stage the whole thing and look at it without any words, just to see what the visual language of the piece is. And then I add words and music and the score. But it doesn't start with the spoken word. Almost all directors start with the written text, and then they stage something based on the words. I don't start with the words. I start with what I see. And then I can add on.

But where do the images come from?

They can come from anywhere. There are no rules. They can come from looking at this paper. From seeing my fingers in this position. They can come from… The world is a library. So, it's full of references everywhere. And it can be from looking at a bag here, from Brazil; I can look to the shape of a piece of glass, and the colour of the glass. I can start with someone wearing a blue sweater and a green-blue pants. I can start with a necklace. It can be anything. This postcard. And then you start, and then add one thing, or take something away, until you build a vocabulary.

Robert Wilson/CocoRosie. Peter Pan by James Matthew Barrie. © Fotos von Lucie Jansch

Scientists say that only 5% of our communication depends on words.

Sure. It's everything; it's what we know. What we see is part of us being here. So, I am very unfortunate in that so much in theatre is based upon what it is that we hear. Usually, what we see is an illustration, or decoration, or only a repeat of what it is that we hear. You read the play, you read the word, and then you make a gesture to express the word.

This theatre, the gesture, can be independent from the word; it can be something pure – on its own. With its own laws, with its own rhythm, and it can be seen as something separate.

So, you have “what I see”, “what I smell”, “what I hear”, and whatever. But let's say, “what I hear and what I see”. And we have this dualism, and this parallelism. And they can reinforce one another. And it is different to be seen together, or to be seen separately. But it can be thought about separately, constructed separately, and so there is a different kind of space in which that happens. And if you start with just what you hear…

If you see a silent movie, then you are free to imagine the sound. So, the soundless screen is free; it is boundless. If you're watching television without sound, you have the news broadcaster, the Hollywood movie; you can imagine the sound of the man's voice, of the woman's voice, the ambient sounds of the room. You are free to imagine. If you are watching the news broadcaster, you begin to see things that you wouldn't have seen if you had been just listening to the news. You see the twitching, you see the fingers doing this, and you see that the eyes are moving, the fingers are moving closer, he moves his hand quickly, he bites his lip; so, you begin to see things that you wouldn't normally see. And with a radio drama – you are free to imagine what the room looks like. How the woman is dressed, how the man is dressed. The audio score and visual screen are free; they are boundless.

It's a little bit like making a silent movie. I always do it silently first, and then very very often, I do what I did today – I turned all the lights out in the room, and I just spoke the text or listened to the sounds. So I don't see anyone, but I can listen more carefully. And then I put the two together. So you have this space and and an ideal situation that you wouldn't have had otherwise. Because they have been thought-out separately, and when you put them together, you find that there are ways that they can reinforce one another without having to illustrate one another. My work is different from that of John Cage or Merce Cunningham, who found, by chance, the relationships between what you are hearing and what you are seeing. Cage worked on the music separately and on the dance separately, and then he put them together for a time while in the museum – for the first night.

My work is more consciously constructed. For instance, in “Lohengrin”, the music of Wagner is rushing and rushing and rushing, and getting quicker and quicker and quicker, and I have 150 people in the choir moving very slowly. So, there is a certain tension between what they are singing and what I am seeing. I just see a wall of people moving slowly, without the music – it's one thing. But when I hear the music being very fast, and the physical movement is very slow, there is a tension being created. And there is a power.

You always say that the task of the artist is not to answer the questions, but to just put them out there. Now you are working not with Richard Wagner's opera, but with the story of Peter Pan. Are there any questions which you want to put out with your production? Or, maybe this is not important in your work with images?

I really think that there is something that we hear, and something that we see. You experienced something, and that is the most important thing. And to experience something is a way of thinking. I see a sunset. I have an experience. And it didn't have to mean something. It is something that I experienced at the moment. I hear the birds. And it doesn't have to mean something. I like to hear the birds. So we don't ask what the birds mean, but you listen to them singing.

Things are too complicated. I was very much influenced by a man named Daniel Stern. I met him in 1967; he made 350 films of mothers picking up their babies in natural situations. When a baby cries, the mother reaches for it and comforts the baby. And Stern filmed that. Afterward, he slowed the film down; and in eight of ten cases, in the initial reaction of the mother, the mother would lunge at the child and the child would shriek back in fear. There are 24 frames in a second: the first frame was of the mother lunging at the child, the next two or three frames were something else, and the following two or three were of something else again. So, in one second of time, it is VERY complex – that what is happening between the mother and child. The mother was shocked when she saw the film; she said – “but I love my child”. So, perhaps the body is moving faster then we think. But it is very complex when Romeo says that he loves Juliet. So, be careful, and don't believe in anything too much.

Thank you, Mr. Wilson, for this conversation. I just want to throw out one last question – do you always draw when you're talking?

(Laughs) Phillip Glass says: Bob is always drawing – because that's how he thinks.

Robert Wilson's drawing, which was made during our conversation