“They go to some dark place. But for me, it’s a wide-open and faraway place”

Elīna Sproģe

28/02/2014

The name Brian Williams (aka Lustmord) marks a certain period in the development of ambient music, and undeniably, spreads out far beyond the borders of the genre. Lustmord has come out with more than twenty albums since his start in the industrial music scene in the 80s, and calls Heresy his debut; he's also been behind the sound design of numerous films, including The Crow, Stalker, and Underworld.

After taking a 25-year hiatus from the stage during the pinnacle years of his career, Brian has recently returned, making every performance a special event.

Photo: Elza Niedre

How did you start? You studied art; did that have anything to do with it?

I think it did. Even though I didn't think so for a long time. While studying, I was really good at it. I don't like the moniker “artist” – not in terms of its meaning, but as a definition of what it was that I was doing. It sounds too pretentious. At seventeen years of age, it was important for me to know where I fit in. School was nearing its end, and I had to think about a serious profession and looking for work. In truth, I was doing everything I could to stretch out this process. I didn't want to go out into the big, wide world and work from payday to payday. At that age, teachers and parents put pressure on you. Especially if you come from a small town, alternatives to a regular job just aren't allowed. I'm British, so consequently, no one really supported my dream of becoming an artist. We were constantly reminded in school that we had to be practical; we shouldn't waste time fantasizing. We must concentrate on a real profession. At the time, I had the chance to study sculpture at the college where I had been accepted, but I didn't like it there. I left after a year. I suppose I had an, ahem... attitude.

As if you don't have one now!

Yes, but at least I'm charming (laughs). The thing is, when you're trying to understand who you are, art school is a place that supposedly inspires and encourages you – be yourself, express yourself using any sort of instruments or palette. That's all fine and dandy, but once you start doing that, suddenly someone says: “Why, not like that! You can't do it that way!” Suddenly, everything is definite – you mustn't do this, nor that! But aren't we supposed to try and discover things? So, I really wasn't doing all that great there, and shortly before the end of the course, we had a meeting and decided that I would withdraw.

When I was eighteen, the punk and industrial scene was developing. It was linked to the dire political situation in the UK at the time. Society was overcome with depression because of the raging inequality and the huge rift that had appeared between the rich and the poor. The unrest was growing, and there was the threat of drastic changes taking place. Everything that was going on at the time was both terrible and terribly interesting. Being in an environment like that, I started to really get carried away by music. One time as I was talking about this, I realized that instead of creating an image with colors, I was doing it with the aid of sound. I collected sounds; I combined them. By putting them together in indescribable, yet self-evident ways, I'd come up with an end product. In this sense, I can call myself an artist (even though I'm not quite comfortable with it) – because I appear to be painting with melody. It sounds cheesy, but it's important for me to conjure up this physical feeling, this illusory place.

How did you come to the decision that this would become music?

I was into punk music at first. I went to concerts a lot, and that definitely influenced me. Everything was just starting then; there weren't big crowds – about 50 to 200 people. There weren't many groups formed yet, either. I went to see Throbbing Gristle – they were the ones that started the industrial movement. Meeting up with them at events, we became friends. I met SPK through them; later on, I was a part of their group for a while. [The industrial and noise collaborative SPK was founded in 1978, in Sydney, Australia; two years later they went to London to put out their debut album, Information Overload Unit. Brian Williams joined the group in 1982. – E. S.]

Chris [Carter] and Cosey [Fanni Tutti] from Throbbing Gristle, as well as the guys from SPK, came to me and said: “Why aren't you doing this? You've got to try it!” And so I made this and that, and I enjoyed the process. Of course, they asked if they could hear some of it. “Not really. I'm just messing around.” But they insisted, and so I recorded a cassette that seemed pretty interesting to them. The cassette was passed along, and Graeme Revel from SPK showed it to Nigel Ayers from Nocturnal Emissions, who had their own label, Sterile Records. They offered to put it out as an album. “Oh, really? That's quite nice,” I said. That's life. How can you plan anything? Of course, you can try to plan and achieve something concrete, but mostly, everything happens unexpectedly. You need talent, skills and ideas, but luck plays just as big a part.

And having the right people around, isn't that so?

I'm from a small town [Bethesda, Wales – E. S.], with a population of about 4000. Of course, nothing really happens there. Yes, I could go to a bigger city (which I later did by moving to London), thereby paving the road for bigger opportunities. You have to go towards them to meet up with them. If you sit and wait until someone knocks on the door, nothing is going to happen.

There were, maybe, three or four interesting people among these 4000. There's probably just one interesting person per one thousand in London as well, but that means that, in total, there are already several thousand of them there...

How did your solo career arise?

Here in Riga we spoke to Stephen [O'Malley, from the group Sunn O))) – E. S.] yesterday, about working together.

I really like working together with other artists. Becoming a solo artist wasn't a conscious choice; it just happened. There are several people I'd like to work with, but it's not that simple. Everyone is busy working on their projects at the different corners of the earth, and planning something is more than difficult. There are also very many great and talented people, but with several of them, it's impossible to spend any amount of time together in one room with them – because they're simply terrible!

The creative process when working together is exciting – ideas are thrown back and forth; some are kept, while others are thrown out. I enjoy what I do, and I also like to do it on my own. The concept is the most important thing to me. Developing it is the most interesting part when starting on an album.

To tell the truth, from everything I've done, I'm most satisfied with my last album, The Word as Power (2013). It's nice if others like what I do, but if they don't, I don't get upset because I know it's a good album, and it turned out just the way I had hoped it would.

The Word as Power (2013) album cover

Your creative aesthetic gives the impression of being a timeless one.

Yes, that is the idea, but I can't be sure if it will work. I have to use the old cliché – only time will tell. Perhaps not all of them, but definitely several of my albums could be timeless. Their sound may be familiar, but it's not really possible to pinpoint what is making it, or what it consists of. Consequently, it opens up a world that is seemingly familiar, but still a bit strange.

It's important to me that music doesn't get stuck in the time that it was created. For example – so that something that I created in 1980 doesn't sound like it's from the 80s. I strive for this independent sound, so that it still sounds the same whether it's the year 1990, or 2000. The only thing that can give you away is not the concept or its execution, but the technology. At times, you can easily sense the technical characteristics of a certain time period. But ever-more advanced technologies have appeared in the last few years, making it easier to avoid this problem. Technology helps to hide technology.

Is the fact that you don't use lyrics, or text, part of this strategy?

Yes, but there are vocals in the first two albums because I was still searching for my mode of expression at the time. In my third album, Heresy (1989), I found the sound I wanted. It's linked to the precursors of the “dark ambient” genre. My music definitely goes even further and broader. I wanted it to take you somewhere. In every album that I create, I have a clear idea of how it will begin and end. How it will turn back around. In this case, lyrics hinder. The objective is to have the listener search for their own words, not follow ones that have been given.

But the title of a song can serve as a kind of clue.

Yes, absolutely. Titles are, of course, partial clues. Every album contains numerous levels of meaning, but at the same time, they are full of obvious references. Details are important to me, but not always with the intent of standing on their own – rather, as irremovable parts of a whole. Some will discover these layers, others won't. Everyone perceives differently, so I don't even try to explain my music – then there wouldn't be any point in doing an album. Listen and give yourself over to it. The same as with a painting – look at it and try to understand it.

I'd say that the titles of the songs are broad gestures that help one tune-in with a certain frame of mind. That's why it's rather funny that most people associate me with something dark. That's not a problem, but it does get rather dull. You already know that everything is fine with my sense of humor! I approach what I do very seriously, but it also give me joy.

The term “dark” is more like a definition of the atmosphere that your music can create, rather than as the place where it comes from.

Probably. So it's about them, not me. They go to some dark place. But for me, it's a wide-open and faraway place.

Another factor is the fact that you used to record in slaughterhouses and catacombs. That had an influence.

Yes; I haven't done that for many years now. I recorded on cassettes, and they don't sound good when copied to a digital format. The equipment itself was pretty heavy – two or three suitcases. Very impractical. And I had to borrow it. It was exciting, but it wasn't easy. And in the end, so much of it couldn't be used.

The most important thing to me at the time was the concept – to capture a specific place. But often times, the place couldn't fulfill the objective. I still sometimes use the better recordings – if they enrich the context. Over the last year, I've collected an unbelievable amount of sounds – a substantial collection – so I can simply not do that for awhile now. Now I use something called “convolution reverb”. It's a rather complicated mathematical process that can record, for instance, a gunshot in your location of choice, such as in a cathedral. Running a sound element through an algorithm, it's possible to create a deep and rich idea about a specific sound. The software is very expensive, but it's completely changed the way in which I work.

Nevertheless, people associate you with this recording period.

That was so long ago, but yes. I understand what you mean. I'm interested in so many different things. But this dark image that I'm associated with – death, sexuality – they are the classic taboo subjects. So much is still being restricted in modern society; certain literature is hidden in the furthest corners of the libraries. It only appears that I concentrate on the dark. Why are we so fascinated with it? Death is a very good example. What happens when we die? I'm interested in the physical aspect, and not the metaphysical, because almost no one ever talks about what happens to the body after you die.

It's strange that you concentrate on what happens specifically to the body, because most people are more concerned with what happens when, suddenly, there is nothing – the lights go out and you no longer exist. The body, and what now happens to it, is no longer relevant.

I'm an atheist, and I don't believe in life after death. It wouldn't be bad if there was, but the thing is, it is impossible for me to know if there is. One can, of course, philosophize about it, but that still won't give us an answer, and there's nothing you can do about it. We'll all find out when the time comes.

That's how people try to prepare themselves.

Yes, but I don't feel as if I should prepare. I believe that there is intelligence behind our existence, but I don't associate that with the idea of God. I've always been a skeptic, and I think that's a good quality to have. If someone insists that God exists, I have an immediate counterpoint – “Show me! Where is he, exactly?”

Everyone has the right to chose in what to believe. If someone tries to get me to believe in God, then that can annoy me. I respect and support everyone's choice, and I'd never go around proselytizing atheism. Just because I put myself into that group doesn't mean that everyone else must as well.

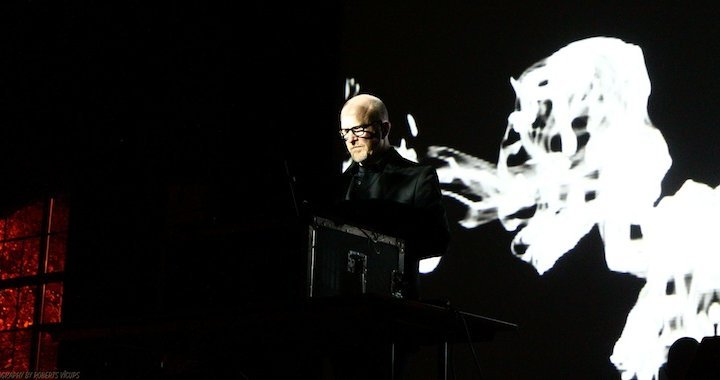

From Lustmord performance in Riga. Photo: Roberts Vīcups

Atheists don't have a tendency to aggregate and proselytize. Certain religions have been doing the exact opposite since the beginning of time.

That's right. I don't have anything against people with strong religious convictions, but if they come knocking on my door, I regard that as being more than rude. I would never go to someone's house and teach them what to believe in and what not to. That would be very rude.

I'm fascinated with the cosmos, with the size of the Universe. It's impossible to imagine, much less fathom. We try and theorize, but we can't grasp it. That is partly reflected in my works.

Are we the only lifeforms in the Universe? If we're not, well then that's bloody wonderful. If we are, then that is also incomprehensible.

That's something we'll never find out.

Yes, it's the same with a lot of things. Life is too short. One human lifetime is not enough with which to reach this sort of consciousness. In my opinion, it's all quite inspiring.

The elements that intertwine throughout your music are associated with ritual practice, which is, in a way, linked to the framework of this world – and the study of existence. How do you look upon this?

The last album is, in a sense, linked with ritualistic music, but without any accompanying dogma. I've always been fascinated by not only this so-called “primitive” music – Middle Eastern-, Buddhist- and Voodoo chants – but also Gregorian chorals and gospels. Although they are religious, they tend to be very enticing and interesting. The focus that it reaches towards has great meaning. Even really bad modern-day Western church music (which is deathly depressing) manages to attain this. Just because I'm not a believer doesn't mean that I don't value it.

In terms of various other art forms – painting, poetry, film – music influences us in a completely unusual way. We remember tonalities, melodies get stuck in our heads, and most people have songs that remind them of certain events in their lives. Music can provoke irrational emotionality. You can also get these abstract feelings by looking at a painting or icon, but the way that music is perceived – its power – is the most exciting to me.

We perceive visual art with our eyes, but it seems as if music enters us through the whole body.

It's possible that a certain part of the brain is responsible; I don't know. But yes, it definitely takes over on an other level. Whether it's a banal love song, or a great symphony, it has the power to create intimate feelings and melancholy, and to make us empathize.

Talking about rituals, from primitive aboriginal tribes in Australia to the Orthodox Church in Europe, music is an essential part of them. In creating musical works, I've used both the Australian Aborigine didgeridoo and the Tibetan thighbone trumpet, the rkang dung.

I'd like to think that my music touches upon something ancient; that it enriches this primeval feeling. It allows for the emergence of something that was here a long time before we arose, and it makes one think about where we came from. It literally allows you to come to this place, open some door, or maybe reverse this feeling of insignificance on a Universal level. In this way, we return to this base level; because I believe that in principle, we are still animals. We like to think that we are evolved and knowledgeable. We are, of course, but the carnivore still lives in us – the way we behave towards one another in our fight for power over this earth – we wage war, we have sex, we eat other species. Actually, a great part of our feelings and emotions are primitive, animalistic. It doesn't hurt to be aware of this.

Your music can't be background music for me. When I listen to it, I give it my full attention; it draws me in and, as you say, creates this parallel environment.

[This environment] reveals itself when the music is playing. When the music stops, the environment also disappears.

Of course, everyone can listen how they want to, but ideally, it should be done when alone, and with a sound system. Definitely not with headphones. They can't handle it, and there's a lot they can't pick up. You know, I like a deep bass. Putting it on just in the background would be a waste of time. The sound must take over. It's also not party music. I know a lot of people who take drugs to it, or have sex to it. When I performed in Sweden, someone in the audience was having sex. It wasn't exactly in the middle of the crowd, but it still seemed pretty fun to me. Maybe they would have done it no matter who was playing, but I liked it.

Dominic Hailstone video projection for Lustmord visualisations. Audio from Lustmord performance in Maschinenfest, in 2011

Talking about playing live and visualizations, how did this all come about?

The greater part, about 90 percent, I did myself. Hiring someone else to do it costs a lot of money. I had pretty clear ideas, and I decided to learn how to do it myself. It took about a year. You'll be able to judge for yourself tonight.

Of course, a couple of friends helped me. Adrian Wyer (London) was involved in one of the sections; he creates digital lava and water – rain and the ocean – for commercials and movies. He worked out a very specific animation which I then manipulate myself. It takes a very long time for the computer to process these images. Dominic Hailstone (London) also helped; he's a terrific special effects artist and he made me some 20- to 30-second-long scenes which I then repeat and stretch out to three or four minutes.

Another friend, Meats Meier (Los Angeles), who also works with Tool and Puscifer, made an animation sequence that, when doubled, lasts about four to five minutes. All of these lads are my fans and they did the work for free.

Most of my friends are artists. Musicians and people from the art world, several of whom work with special effects. Some of the best sculptors in the world work specifically in this field.

How did you decide to create the corresponding visuals?

Live shows tend to be pretty boring; it's not the same as listening to the album. Over the years, the studio had become my instrument; in that case, how does one then do a live show? How do you transfer a whole studio to the stage? And who the hell wants to watch me as I just stand there for hours and produce some sounds?

With computers becoming ever-more powerful, a whole studio can fit into them now. Now you can just put everything on your laptop and take it along. Nevertheless, watching “me at the laptop” still doesn't sound all that exciting. I wanted to visualize things. It was important for me to create them in a way that is similar to how I work with sound. Of course, it is a very different process, but I wanted the images to be abstract enough. Like when you said that music pulls you in – it makes you lose yourself – I wanted to do the same thing with video.

The idea is very simple. They are templates. You know, people have always looked at fire, smoke, or the clouds, and have seen in them shapes that really aren't there. Comparing ourselves, yet again, to the animal world, our brains have been created (that is, if there is a Creator) to recognize corresponding templates. If there aren't any, the brain will create them itself – by visualizing ships and airplanes in the clouds, or connecting the stars into constellations. I wanted to do something similar. In the video of flames of fire, people see demons and angels, even though there isn't anything like that there – they're just flames. In this way, it relates to my music. Everyone experiences it differently. It's funny how people often say: “How satanic!” Even though there's nothing like that there; why do they think this?

Just like after my performance at the Church of Satan, everyone thought I was a satanist [the Church of Satan celebrated their 40th anniversary on 06.06.2006 with a High Mass. Lustmord was invited to play, marking his first live performance in 25 years – E.S.] How could I refuse such an offer? It was so amusing! I've also performed in several churches, but no one thinks I'm a Christian because of it; it's pretty funny actually, isn't it?

The loudest events are the ones most likely to get attention, of course.

Yes, and then you're immediately labeled.

The unknown and the unknowable have always attracted people, just like the flames in your video.

Exactly! This is, again, related to the primeval, the incomprehensible. The bonfire has had great meaning throughout the development of civilization. Stories were created around it, rituals happened around it. The darkness surrounding it held horrors, so the fire was associated with safety, with being together. My visualizations, along with waves of sound, also create something hypnotic. But there's a very fine line between being hypnotic and being boring.

Songs of Gods and Demons (2011) album cover

How about the album design? In which cases do you create them yourself, and when do you decide to work with an artist? I really like the album cover for Songs of Gods and Demons (2011), with the embroidery.

My wife made that. She has a whole series of embroideries with scenes of torment, and a great number of books on torture. They're hers, not mine (laughs). Tracey's [Tracey Roberts] first solo show was at the Museum of Death in Los Angeles. She's great!

But in terms of the other covers – the layout is hugely important. When I started, I made everything myself; I always have a lot of ideas. However, it's much easier if you have someone who helps. When I work with others, I can be quite critical because details are important to me. It doesn't matter whether I'm working on an album or the soundtrack for a movie – I clean the audio of all clicks so meticulously, that many people think I'm crazy – because who's going to notice? I'll notice them!

The same goes for the visual layout and fonts. I'll quibble about millimeters (laughs). I try to apply this to everything I do. I really like people who have this sort of approach to work, because if they don't, you can immediately see the difference. It looks sloppy, unfinished. You have to be a bit crazy to do all of this. It takes up a huge amount of time.

What about Lustmord's graphic identity – the hexagon? Does it have a specific meaning, or did you choose it on its visual merits alone?

That choice was pretty random; there's no secret behind it. I wanted an indirect meaning, so it's more of a graphic-design element. There are frequently things in my works that could seem like clues. I like this game with meanings. It creates an air of secrecy and evokes different reactions. They are instrumental albums; there's no text. There's nothing to tell you what to think. Whatever you feel, it's of your own making. Without a doubt, how something is presented has great importance. Without the corresponding packaging, the music can be interpreted in diametrically opposing ways. But this is where the previously-mentioned templates show up again. I want to create the feeling that there is something hidden there that is more-than-meets-the-eye. Many won't crack it. You need a key to turn. The main thing is that they do it themselves.

Many of my fans are artists that listen to my music as they work. They say that it helps them find additional inspiration, and that's the greatest complement – to be part of the creative process in which something great is created. There's nothing in my work that would make them create something specific; rather, it brings them to a certain state of mind. Getting to this previously described “place” is dependent on you alone.

If you don't associate yourself with something dark, then why the name of Lustmord? Is that also supposed to be taken ironically?

Actually, that wasn't a joke. That was a very conscious decision at the time.

It literally means “murder of a sexual nature”.

Yes, it's “murder done for sexual gratification”. It can't be called rape, really. This is a quite specific term, and there aren't many examples of it. One of the best known is Peter Kürten [a German serial killer who was called “The Vampire of Düsseldorf”. He killed and sexually violated numerous adults and children in 1929. – E.S.] Most acts of violence (I wanted to say “acts of sexual violence against women”, but it's clear that there are also male victims) are not about sex/rape, but about power. Consequently, most of the victims are usually women because men are more powerful, and they are the ones capable of unimaginably sick things.

I took this name in 1980, or '81. I was around eighteen years old, and I wasn't thinking about how it would sound thirty years later. If I had been older, I probably wouldn't have chosen such a name. I couldn't have known that it would turn out to be a life-long project. [Making music] was just something that I liked to do at the time. That time is very different from today. [The name] made me more likely to be noticed in a record store or in a magazine. That's why I wanted a name that created intrigue; and also, it had various meanings. My choice was also based on the name's visual quality – it had to look graphic. I didn't think there would come a time where I'd be selling records all over the world, and that people in Germany would find out about it. Most people don't know German or Swedish, so they don't even read into it that way. A while ago, I regretted having chosen the name Lustmord; but it wouldn't be logical to change it so late in the game. Everything is OK now, because it's clear that my creative work is not about that.

Words and semantics have great power. I also touched upon this theme in my new album, The Word as Power. It's the same with there being so many indecent words which are deemed unacceptable for saying out loud – and just because they are entwined in stereotypes. The word itself isn't bad, it's the meaning that has taken on the “bad” connotation.

Lustmord performance in Maschinenfest, in 2011. Oberhausen, Germany

Just like if someone doesn't know the true meaning of the word Lustmord, they could take the English meaning for lust, and the German meaning for mord (murder), and come up with the rather lyrical name of “lust-murder”.

Yes; you yourself see these various meanings, but many do not.

Since you've begun performing again, you're at it quite often.

Yes, I've had about 14 or 15 shows in eight years.

What is special to you in this process?

Playing live is completely different. The album is more about a concept. When performing, I use a bass that most people can't reproduce at home. In this way, I reveal the true sound. A huge racket that lasts for 52 minutes (laughs).

I'd like to make longer shows. But people have bought tickets, and I don't want them to be bored. That's why I like to stop while they still want more. I always improvise, but there are a couple of things that I like to repeat because their sound is so effective. I was just at The Hague. Somewhere in the middle of the concert, I noticed that something was off – the crowd wasn't picking up the hypnotic bass element. That's the way it is with performing live – you never know if it's going to go off without a hitch. The advantage with improvisation is that, at times like that, you can set the track in various ways. I like the fact it's not just a matter of pressing “play”.

Does this somehow influence the way in which you work on your albums?

Not really, because the albums are in my head. I already had the idea for my last album twenty years ago. It's the same with the next ones; I just have to find the time to do them.

Even though making sound design for movies and computer games is your main source of employment now, does the work still fascinate you?

Yes, definitely. I'd do it even if they didn't pay me, and if often seems strange to me that someone actually wants to pay me for doing it (laughs). It's a very slow and time-consuming process. Nevertheless, I'm lucky to be among those people who can make a living doing what they love, because it's hard to get by with just music alone. The main thing is inspiration. If I happen to be working on some material and can't find any inspiration, it's not easy to get excellent results.

What inspires you in these cases?

I don't have any good answers to this question, even though I'm often asked it. I'd have to say it's life, and the experiences that life gives you. I'm inspired by conversations like this one, by meeting friends, by films and books. Everything. I go to the desert as often as I can. When I moved to America twenty years ago, I fell in love with the Southwest.

This may be a weak answer, but these are the details that make up something bigger. Like meeting with you. I won't say it will inspire me to create an album, but that's only because I don't want to share my millions (laughs).

I cannot not make music; it simply comes out of me. Like the things I say. If you have nothing to say, then there's no album.

That's the answer I was waiting for, because that's the way it should be. At the same time, there are people who don't get inspiration from anywhere, which is why it's important that you indicate that it is life itself that feeds you. You're lucky to be able to see that.

Yes, that's true, and I value it.

Many people ask me how do I achieve things technically, how do I get a certain sound. Often times, they're interested in that because they want to reproduce it. I can, of course, show them; it's nothing complex, it's not magic. But what's the point? The process is easy enough, and you can get really good equipment these days. But what you can't teach is aesthetics and an individual approach. Because really, I'm just combining sounds in such a way that seems pleasing to me. When people want me to tell them how to do it, they are, in a sense, robbing me. It's the same as describing a beautiful landscape – it's obvious, but you can't really explain why that is. It's the same with sound. Clearly, some noises are awful, some are interesting, and others are wonderful. How to recognize which is which? You can't teach that.

It's similar to cooking. Just because you know the recipe doesn't mean you'll get the same flavor. It depends on whether you're doing it by the numbers, or with love.

Yes, it's the same with James Brown, who we have on in the background right now. Either you have funk, or you don't have funk. You can show someone the steps, but that doesn't meant that he will dance well.

Elīna Sproģe and Brian Williams (aka Lustmord). Photo: Elza Niedre