The Magic Realism of Soviet Times: the Story of One Generation

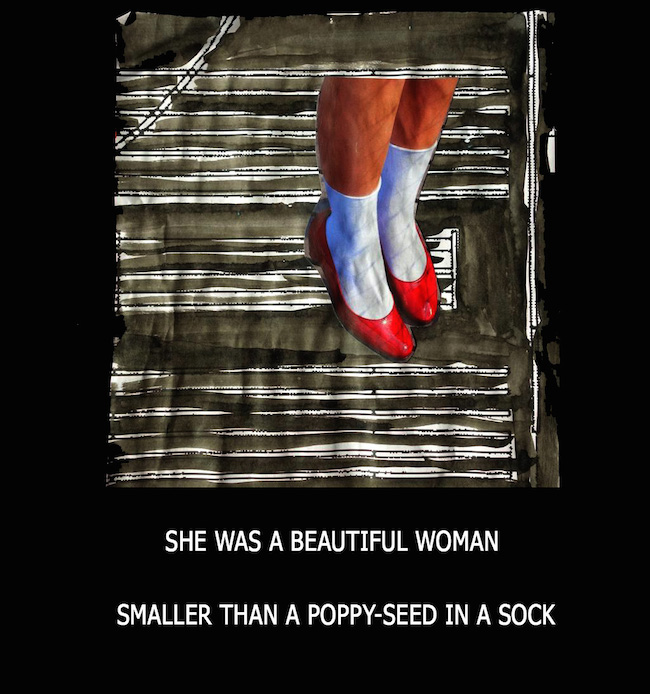

Review on Marta Vosyliūtė’s film “The Life and Death of a Humanist Woman, or Be Smaller than a Poppy-seed”

Rasa Baločkaitė

16/06/2017

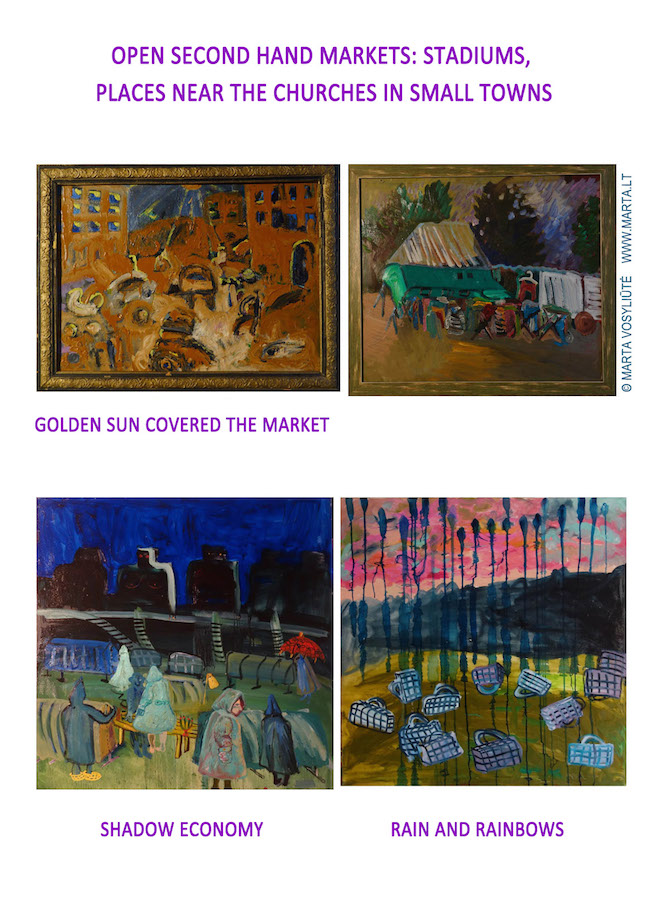

Marta Vosyliūtė’s film “The Life and Death of a Humanist Woman, or Be Smaller than a Poppy-seed” is a story in seven parts, made up of 328 original paintings, and accompanied by the author’s brief comments in the subtitles. In the words of the artist, it is “a post-Soviet artistic study”. What she tells here is the story of the post-war generation and this generation’s social trajectory – from kitchen gardens and greenhouses to universities and conferences, from black earth hotbeds, planting and weeding to writing articles, from the stagnating peace of a provincial town to the capital with its real or alleged possibilities. This is a story that, like magic realism, balances between history, art, fiction and documentary. Subjective history – the unnamed and undocumented experiences and memories – is all that usually remains on the other side of the text and is not included in the annals, archives or textbooks. Speaking in trendy academic terminology, one could say herstory, but the agent’s femininity collapses and dies at the beginning of the second act, not disclosed as it was supposed to, as if illustrating the sexual indifference typical of the Soviet period; so, in this narrative, gender is not a decisive factor.

Thus, the language of symbols and metaphors: what it meant to the post-war generation to “live” at a time when the country “was being developed in all directions”; the fears and traumas of war were silenced, but not yet gotten over, while the golden mouth of St. Radio fueled illusions by lying that “the world is exciting and everything is possible”.

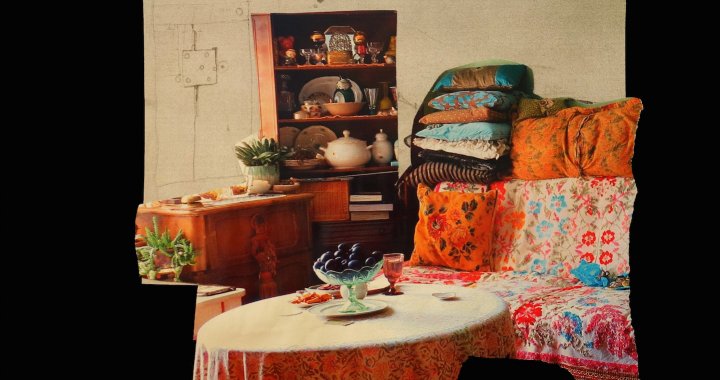

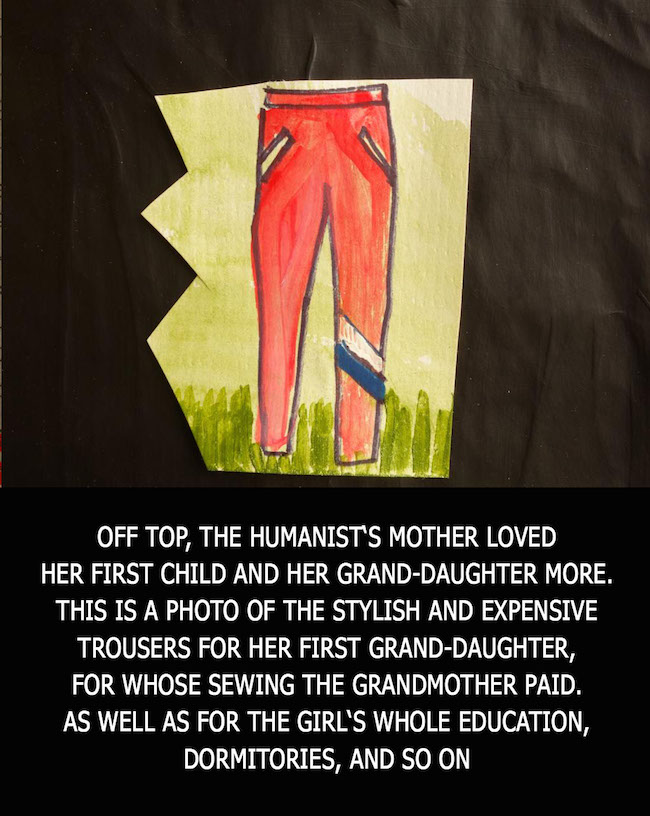

Part 1, “On War and Fire”, is about the origin and the ways of formation of the first post-war generation. On an emotional level, their daily world of was characterized by simplicity, shortage and reticence. The trivial plains, the smells of lilac and jasmine; the unequally shared love of parents; the outgrown clothes inherited from older children – “the sloughs of her [older] sister”; and a radical lack of privacy, which manifested itself in shameful collective visits to the town’s public bath. As well as the post-war trauma and other things you could not talk about – above the provincial town, there were always “clouds of misunderstanding” which, however, never lashed out. And, of course, nature. Nature has a special therapeutic function here: “There were no psychologists, palm-readers and horoscopers [sic] at those times, so everybody would lick their war wounds on their own. […] And what can you, ordinary person, do about it? All that is left to do is have nature’s beauty therapy.” After this movie, you will never see the tapestry depicting moose and lilies as innocent or boring.

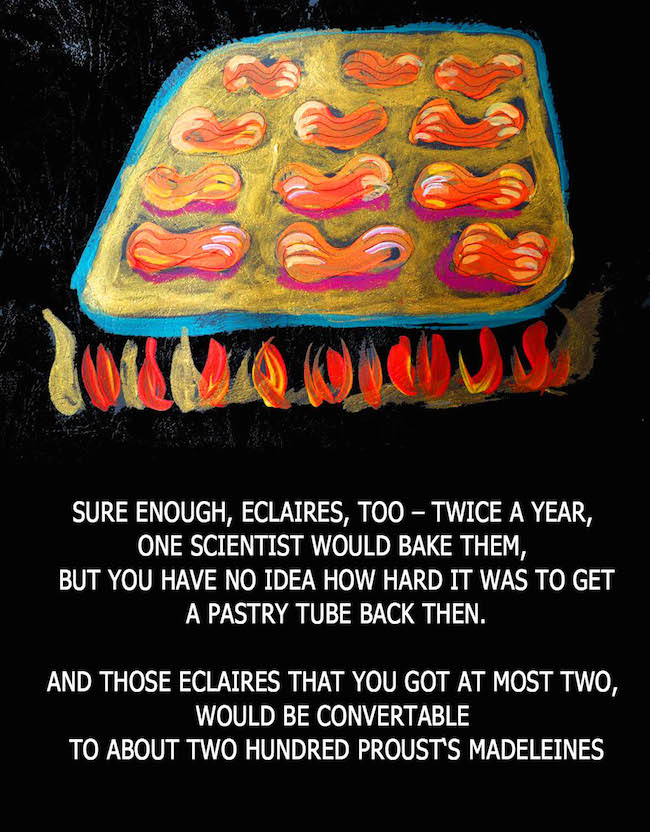

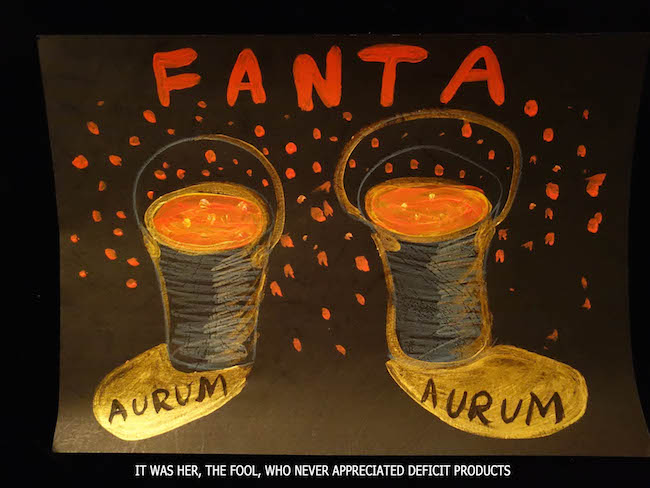

It was a world of ongoing conversion – mushrooms and berries would be converted to wristwatches and bicycles, urban goods, commodities. Whereas feelings were converted to food – here, people rarely talked about love; they would express it by jams, canned vegetables, as well as sausages and other meat products. There’s nothing one can do, it was the war-affected generation – in those times, a slice of bread meant more than a thousand words, while silence helped save people’s lives more than once. One generation starved physically, while the other did it emotionally. Once, in Soviet times, the mother “gave the weird humanist, who never needed anything material, a refrigerator, which the mother brought by train, all by herself” – the fridge on the shoulders of a tired provincial woman is nothing other than the symbol of the emotional burden and unspeakable feelings that the mother expressed in the only way that she knew – by objects. What the war and post-war period taught the older generation was to work, save, and keep quiet. The younger generation grew up surrounded by “clouds of misunderstanding” – no one ever taught them how to live and how to fight; they learned to rely only on themselves, and forgive a lot, “because the mother’s life was not strewn in roses, either”.

One more thing that stands out as a distinctive characteristic of their environment is sand: “Her small town was full of sand, sand and sand”. Sand is a material that you cannot use to create something durable, put down roots in, or build a foundation on. On the emotional level, the equivalent of this “sand” is the iconic story that her mother would always tell at the family gatherings – about the war period when she, full of despair, would want to jump into the well with her two children. Children, of course, should never hear such things, because these stories make them lose a fundamental sense of security – when the ground under their feet slips like moving sand, and the world starts to look like an uncomfortable and unpredictable place. Even though the film does not directly address trauma, this is considered a classic definition of the latter.

This sense of security is what Part 2, “Brain Convolution Carving” speaks about. For this generation, the post-war generation, the world arises before their eyes as a rebus, made up of their parents’ traumas, the silent indifference of the people around, the lack of material goods, love, and privacy – as well as the “clouds of misunderstanding”. What they sought was not to conquer the world, but to understand it: “She never ever needed publicity, only peace”; “She never needed any kind of kitsch or bullshit”; “She did not play any psychological games. […] Even when she was being forced to”; “The world was very complex; she never argued, but kept speculating”. In those days, as the author emphasizes, there were no psychologists, palm-readers and self-help books. Food and material goods became a form of communication and an expression of affection, so that parental love turned into canned vegetables and meat products: “Meanwhile, her mother, for a long time, would send her food to the city. She kept cooking and sending it”. Those parcels warmed her, but did not help her answer the question: “What would her life be based upon?” Science would promise to give her answers, but it never gave her either the answers or security. It did not give her any other things either, for instance, money, love or honor.

Part 3, “Vilnius and the University”, is dedicated to Vilnius with its “libraries, art and bananas”. This is a city with “a smell of miracles”. She plunged into the waters of euphoria – it’s like the sacrament of baptism, washing away the sins of provincialism, and promising heavenly paradise to the initiated, but as it turns out later, heaven belongs only to the chosen ones (i.e., men who have a piano at home), while the others remain, in the best case, in the lobby of paradise, purgatory.

Part 4, “1 Husband / 1 Child”, continues her existence between the hammer and the anvil, between emptiness and confusion, between flight and the household. It is here that her child appears in her life, but the latter’s trajectories do not change because there are already two imperatives that give structure to the hero’s life – insecurity and responsibility. As well as into her daily life, some serious and unnecessary things also fall into her consciousness, filling the hollow with chaos and a sense of heaviness. Her vision is growing weak, but it is counterbalanced by her growing awareness – like the legendary Vanga, our hero, by losing her vision, gradually gains more wisdom. The child’s father was “a noble, he had a piano […] at home”, but he never shows up – he is the chosen one, one of those who own the capital’s heaven. The shadow of threat that would follow our hero is passed down from generation to generation – “in the backyard, the Humanist’s child would play childhood” – perhaps s/he was only playing, but perhaps s/he only pretended to be a child, when, in fact, s/he became an adult before it was time, parentified, and realized long ago that, in fact, not everything was as good as s/he was told that it was.

Part 5, “Science Is All”, highlights the economy that was born from threat and deprivation – the economy of saving time, resources and emotions. “She never wasted her time – even at the seaside she would participate in foreign language summer camps”. This section could just as well be called “One Body IS a Body” or “Survival Strategies”, as it makes a perfect illustration of a lonely traveler in life, one who fervently believes in the desperation of a science pilgrim and is constantly fighting demons, both internal and external, in addition to temptation, intimidation and other challenges.

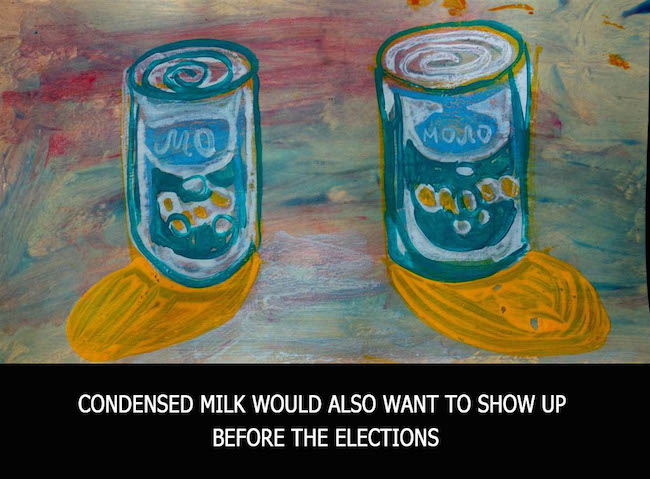

Part 6, titled “Red Clouds, Red Skipping-ropes, Red Caviar” actually does resemble red caviar – a true delicacy. The main characters here are the joyful red people, Mister-Smiles with “the party with the goods and the sense of security”, standing behind their backs, and all the others, too, would occasionally get some crumbs from their table, while the Humanist woman’s child would cherish his/her imported shoes so much that they “died moth-eaten, but never worn out”. I will not recite the jokes, but talking about injustice has never been so entertaining – starting from the times of “The Forest of the Gods”, a novel by Lithuanian writer Balys Sruoga, where he describes his own experience in a Nazi concentration camp.

In Part 7, “The Old Age, or Jesus Never Showed Up”, the story begins to crack, the hero’s relationship with the world and her neuronal connections start to break off, the algorithms get stuck, and finally she ends up in the same situation where she was as a child – no, not left with ruins, but with St. Radio, and with a note lying around on the table, written by the hand of Death: “So much is left of your life”.

What were the post-war generation’s life trajectories, how did they subjectively experience and perceive the threatening post-war deprivation, dreams, city, culture, nomenclature, science, femininity, motherhood? These experiences, subjective involvement, threats, traumas, grievances, ideals, and ambitions are revealed through texts and symbols – blackberries and raspberries in baskets, white stockings, red shoes, the Vilnius department store, demons, page-boys, unicorns, dry lemonade, promenades...Magical Soviet realism, miracles happening in the trivial world of shortages and injustice...the curse of the province, the desirable but painful transformation from Cinderella to Humanist, the sirens who seduce people in the capital, the red demons – capable of conjuring the imported shoes or dry lemonade out of thin air, a lot of pain, faith, and hope.

Slavoj Žižek, in rephrasing Ludwig Wittgenstein’s saying Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen (“What cannot be spoken of must be passed over in silence”), has said: Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schreiben (“What cannot be spoken of must be written about”). Marta Vosyliūtė’s film is based on exactly this principle. What we cannot speak of – we must write about. And if you cannot even write – then you can draw. That is how all of it was done.

Five out of five geese.

Marta Vosyliūtė was born in Vilnius. She graduated M. K. Čiurlionis Art School and studied in Vilnius Art Academy the subject of Stage Design, and has got BA (1999) and MA (2001) diplomas.

In 2006 she has finished postgraduate studies.Marta Vosyliūtė is participating in painting, drawing and other shows and has made several personal exhibitions. She has done stage design for more than a 30 plays in drama, musical theatre and dance

performances all over Lithuania and is specially interested in non traditional spaces for performing arts. Also writes critical texts on different culture themes, essay texts, participates in conferences. www.marta.lt