“The Damnation of Faust” in Berlin

Film producer Terry Gilliam’s production at the Berlin State Opera

19/06/2017

Sometimes scandals happen just when someone had fervently hoped they wouldn’t. Or when someone hadn’t even thought about the possibility of it happening. As the tragic Russian poet Anna Akhmatova once said: “We are not meant to foresee how our name will echo.”

On the opening night of Hector Berlioz’s dramatic legend “The Damnation of Faust”, conducted by Sir Simon Rattle at the Berlin State Opera (Staatsoper Berlin) on 27 May, there was a palpable sense of elation. Showing throughout June, this opera on a German cultural figure as interpreted by a French romantic, and as directed by American-born film producer Terry Gilliam (of British television show Monty Phython’s Flying Circus-fame), was awaited with joyful interest. Although more than forty years have passed since the dark-humor-filled BBC comedy sketch show was on TV (Monty Python was in production from 1969-1974), and Gilliam has made twelve feature-length films since then (including Brazil and the Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, which was shown in Riga as part of the educational film series Things You Must Not Be Unaware Of), his name is still most associated with the highly original Monty Python world of comedy.

This was Gilliam’s first try at directing opera. However, the director’s cinematic journeys in time and imagination – which have always broken new ground through all known bounds of reality and have opened up ever-newer spaces – seemed made for the dramatic legend authored by the modern and free-thinking Berlioz, an opera untethered to any of the canons of classic opera.

After having read Goethe’s Faust, Berlioz was so preoccupied with the material that he composed music for it wherever he happened to be at the moment. Nevertheless, about twenty years passed before his obsession with the subject materialized into a finished score. First performed in 1846, the opera tells the tale of Goethe’s Faust episodically, with large breaks in time and space, and a unification of elements of musically completely different genres into one whole. Berlioz called his work “an opera without stage or costumes”, regarding the staging practices of his day as utterly ineffective for the new composition.

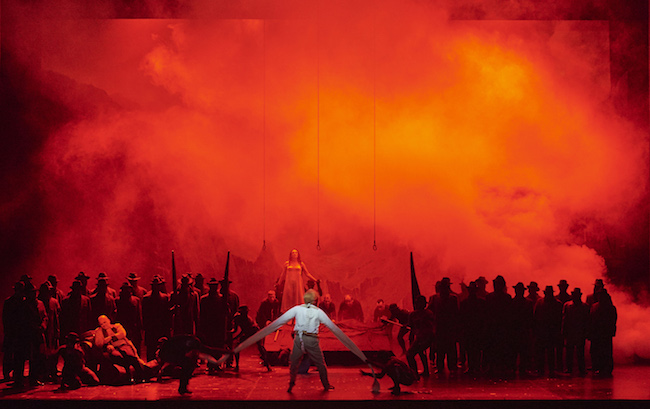

Charles Castronovo (Faust), the Staatsoper choir, a dancer, Florian Boesch (Mephistopheles). Premier of The Damnation of Faust, 27 May 2017. Photo: Matthias Baus

Faust is the story of human beings’ desire for knowledge. The scholar strikes a deal with Satan in order to know more than it is humanly possible. But Faust’s encounter with the phenomenon of love, contrary to Goethe’s hope that “the eternally feminine raises us aloft”, does not save Faust in Berlioz’s work – but damns him.

When other directors stage The Damnation of Faust, they often have the urge to head off into futuristic visions with the scholar and the Devil; Terry Gilliam’s time machine travels in a radically different direction. Gilliam has created his own story on top of Berlioz’s fragmentary retelling of Faust, calling it a journey through German art and history from the 19th century to the mid- 20th, one that arcs from German romanticism with scenes worthy of Caspar David Friedrich’s lone wanderer atop a rocky crag, to the brutal horrors of WWI as depicted in the visual studies of Otto Dix, and then on to the successive debut of Hitleresque thinking in Europe as echoed in Leni Riefenstah’s poetic images glorifying the human body. Gilliam has said that, in the mystical and irrational thinking of the German romantics, he has perceived the roots of the 20th century’s global tragedies. As a professional creator of animated comics, he has executed this view of his on stage with great simplicity, but with the thrilling mastery of a cinematographer.

Charles Castronovo (Faust), Magdalena Kožená (Marguerite), Florian Boesch (Mephistopheles). Premier of The Damnation of Faust, 27 May 2017. Photo: Matthias Baus

During the period of nationalism in Germany, Faust was interpreted as an Aryan – as a super-human. In Gilliam’s version, Faust becomes a Nazi. Mephistopheles coaxes him into falling in love with a Jewess. Although in public she wears a German folk costume and a wig with the blond plaits of an Aryan, she is spied on, arrested, and deported to a death camp. In order to save his love, Faust signs a contract with Mephistopheles, but Faust, of course, doesn’t save anybody, and just falls directly into the pits of hell himself.

Terry Gilliam is not the first American film director to have tried his hand at dissecting the theme of the Nazis. Long before him, through the eyes of laughter, the horrors of Germany were looked at by Charlie Chaplin and the German expatriate Ernst Lubitsch. In 1943, Walt Disney sent his animated characters to Hitler’s Germany, where Donald Duck ended up doing forced labor in a weapons factory (Der Fuerer’s Face). In the animated film Education for Death, Disney illustrated the phenomenon of how a person who has been brainwashed since birth is ready to become cannon fodder of his own free will. Nobel Laureate Thomas Mann, who also emigrated to the USA, studied the roots of national socialism in German cultural history in his novel Doctor Faustus, which he worked on from 1943-1947.

Florian Boesch (Mephistopheles), Charles Castronovo (Faust), Magdalena Kožená (Marguerite), the Staatsoper choir, a dancer. Premier of The Damnation of Faust, 27 May 2017. Photo: Matthias Baus

In post-war Germany (albeit quite late in West Germany, basically beginning only in the late 60s), all of society intensely analyzed the inhumane core of Nazism and the reasons for its success in the consciousness of an average person. Starting with elementary school, Germans were told about the concentration camps and shown the documentary post-war film material of the mounds of bodies being bulldozed into mass graves. Germany’s most powerful artists and intellectuals have analyzed the causes behind the rise of Nazism, revealing the phenomenon in all of its complexity. It has been a huge and unpleasant job, spanning for more than seventy years, to make today’s society different. Even today, not a day goes by in which German television doesn’t show a documentary or other program dealing with Hitler’s Germany.

Subsequently, presenting in the summer of 2017 a simplified comic to this kind of an audience seemed to many a patronizing slap in the face. When the choir came upon the stage wearing Nazi uniforms at the end of the Berlin premier, the audience refused to applaud; when the directing team walked onto the stage, a chorus of “boos” erupted, with a few “bravos” interspersed. This, however, was only a subtle preview of what was to come in the following day’s press.

Charles Castronovo (Faust), the Staatsoper choir, a dancer. Premier of The Damnation of Faust, 27 May 2017. Photo: Matthias Baus

“No one at the Berlin State Opera can deny that they didn’t know what was being rehearsed here in these last weeks. No one at the Berlin State Opera can deny that they didn’t notice the huge amount of brown shirts that were being sewn for the choir, the boxes of armbands and the gigantic swastika on which Faust is killed at the end of the opera...” is how Berlin’s largest newspaper began its scathing review in which the 76-year-old American director is chastised for the irresponsibility of his simplistic approach. And then there’s the Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of the largest and most influential German newspapers, which called the appearance of this production on the German cultural scene nothing less than a scandal.

Meanwhile, Terry Gilliam is working on his latest film and, according to the German press, didn’t even participate in the rehearsals at the Berlin State Opera.

Florian Boesch (Mephistopheles), Charles Castronovo (Faust), the Staatsoper choir, a dancer. Premier of The Damnation of Faust, 27 May 2017. Photo: Matthias Baus

Sir Simon Rattle, a big fan of Terry Gilliam, sees the cinematographic aspect of the production as its greatest quality, especially the silent-film-era way of thinking which has been creatively and convincingly utilized throughout. But in terms of the production’s basic premise, Rattle asserts that he has no idea how Gilliam came up with that. In the program notes for the production, Gilliam writes: “I always approach a show naively. I listed to a recording of the opera and thought: ‘Horrors!’ My first reaction was: ‘I have no idea what to make of all this!’ The work’s structure is built so that wonderful numbers are continually hindering the activity. Then I thought: ‘What if I laid a completely different story level over the whole thing, one which everyone knows and that would guide the story forward in another way?’ That was my idea. I am a great admirer of German culture, and it was my hope to tell the story on an artistic level, starting off with German romanticism, going through expressionism, and ending with fascism. From organic, natural, and beautiful shapes we arrive at deformed, jagged, and broken ones that conclude in right angles and corners – the swastika. Visually, it is a beautiful idea, indeed.”

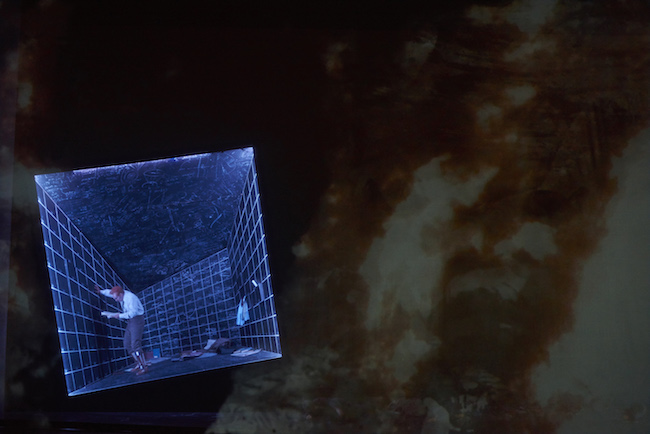

Florian Boesch (Mephistopheles), a dancer. Premier of The Damnation of Faust, 27 May 2017. Photo: Matthias Baus

It is important to note that Gilliam’s The Damnation of Faust was not made specifically for a German audience but a British one. In 2011 the production premiered at the English National Opera in London, where it was successful and received favorable reviews from the critics. The original production was a joint project with the Palermo and Flemish opera houses, and only now has made port in Faust’s spiritual home of Germany.

Cooperation among several countries in the creation of an operatic production gives local audiences the opportunity to experience more than just what the budget of one opera house can afford. Often times, this is a fruitful venture because the stakes are placed on top-class and very original artists. However, the coming together, or rather – the clashing, that has occurred between Berlin and the British version of “The Damnation of Faust” leads one to think about the problematic aspects that can arise from this still-new model of global opera production. Fragile and very individualistic threads connect a live artwork, its creator, and society. It is not something that can be simply packed up with the stage set and props and transported off to another culture.

Charles Castronovo (Faust). Premier of The Damnation of Faust, 27 May 2017. Photo: Matthias Baus