Why Is Baltic Art So Little Represented On The International Scene?

That’s the question Arterritory asked the Swiss-based art critic Simon Hewitt, who regularly visits Eastern Europe and was a member of the Jury at this year’s Art Vilnius

Simon Hewitt

19/08/2015

At this year’s Art Basel – unquestionably the world’s most prestigious contemporary art fair – none of the 283 exhibiting galleries came from the Baltic States.

There are no artists from the Baltic States in ArtPrice’s current listing of the world’s 500 Best-Performing Artists.

‘The art market in this part of the world is wild and undeveloped, and taking shape only gradually’ notes Astrīda Riņķe of Riga’s Alma Gallery.

‘We still have a lot to do in terms of raising awareness among international institutions and collectors’ admits Tallinn dealer Olga Temnikova.

For an outside opinion on the artists of the Baltic States, I turned to New York gallerist Oksana Salamatina – who frequently visits and participates in international fairs, showing works not just from America and her native Russia, but also from Eastern Europe… like an intriguing installation by Slovenia’s Gasper Jemec at this year’s 2015 Venice Biennale.

However, when I asked Salamatina who her favourite Baltic artists were, she was unable to name a single one.

‘People don’t know much about them’ she shrugged. ‘It has nothing to do with being good or not being good – it’s all about PR and marketing.’

Artists: Who Stands Out?

I met a similar response when I asked various Baltic galleries to identify their country’s finest artist. They hummed, hawed and were unwilling or unable to cite a single outstanding name. Conclusion: no one artist stands out as a flag-bearer for his or her country, or for the Baltic States as a whole. The region lacks a superstar to lead a PR assault on the art-world.

Merike Estna

The finest Baltic artworks I have come across include the installations of Andris Breže, the abstract paintings of Barbara Gaile and the multifaceted output of Merike Estna, herald of the younger generation.

Perhaps the two Baltic artists who stand out most, however, are Ritums Ivanovs and Žilvinas Kempinas.

Ritums Ivanovs

I first encountered Ivanovs’ paintings on the Rīgas Galerija stand at Art Moskva in 2007, then at Scope Basel in 2009, and he featured in the Heroes Corner section (devoted to East European Art) which I curated at the Budapest Art Fair in 2010. Although his unmistakable blend of Op Art and refined figurative technique has tremendous wall-power, his international outings in 2015 have been confined to Latvian group exhibitions in Abu Dhabi and provincial Germany (Mainz). Why has he not soared to global stardom?

Three possible explanations spring to mind: his preference for understated monochrome (predominantly blue) rather than eye-catching colour; his refusal to quit his native Latvia to further his career; and the recent downsizing of Rīgas Galerija, which promoted him internationally for many years.

Žilvinas Kempinas

Žilvinas Kempinas, on the other hand, moved from Lithuania to New York 17 years ago, and has been represented internationally by Yvon Lambert. His work, however, is found less often in the gallery than in non-commercial venues: the Venice Biennale in 2009; Basel’s Tinguely Museum (a sublime solo show) in 2013; an epic outdoor installation on Long Island in 2014….

Even so, the critical esteem Kempinas enjoys has yet to translate into truly global celebrity. Is this because he, too, works mainly in monochrome (metallic tape)? Or because only his smallest and least ambitious works are suited to the gallery?

The Vagaries Of International Taste

‘The very fact that Baltic artists are not inclined towards gloss and instant fame makes it much more challenging to promote them internationally’ notes Astrīda Riņķe. ‘I think that this is primarily a question of time, because there are some very interesting and powerful artists in the Baltics whose work is characterized by their Nordic reserve, depth and diversity.’

.jpg)

Linas Blažiūnas

To me that reserve is quintessentially characterized by the graphic work of Linas Blažiūnas, which I discovered at Art Vilnius in 2011. It is harrowing to learn that Blažiūnas has only ever had one solo show outside his native Lithuania (at Galleri NB, in the small Danish town of Viborg).

Nordic reserve and monochrome restraint are, of course, at odds with the sort of art that enjoys greatest global popularity. Basquiat and Koons head the ArtPrice Index, pursued by no fewer than 46 often eye-easy Chinese artists in the Top 100. The leading names amongst Russia’s current art generation, such as AES+F, Oleg Kulik and Oleg Dou, appeal to similar glitterati values.

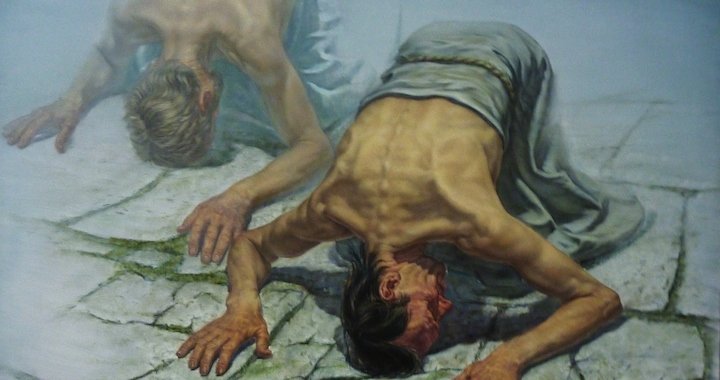

Another powerful component of the Baltic States art scene is equally ill-suited to international appeal: the Academic tradition of Figurative Art, whose commercial outreach – as a style many have been familiar with since their Soviet childhood – is essentially domestic.

Paulius Juška

Traditional teaching remains entrenched at the Art Academy of Latvia (prompting many students to head to London, Hamburg or Belgium), and some of its professors – like Normunds Brasliņš or Valdis Krēsliņš – are among the most popular artists in Latvia today. The same applies to Žygimantas Augustinas and Paulius Juška – both graduates from the Vilnius Academy – in Lithuania. Figurative Art duly dominates the stands at the Art Vilnius fair each Summer, some of it highly skilled.

The overseas markets for such art are not, though, to be found in Western Europe or at international fairs… but in China and, to a lesser extent, the USA. Prospecting these markets is beyond the means of galleries from the Baltic States.

Galleries Lack Means

Just as the Baltic States lack a superstar artist, they lack an undisputed number-one gallery.

Estonia’s Temnikova & Kasela take part in the most international fairs. In Lithuania, Vartai probably have the busiest and most international programme. Deprived of its commercial premises, can Rīgas Galerija still be considered the pre-eminent gallery in Latvia? The situation in each country appears, to an outsider, confusing and fragmented – Vilnius alone has around 20 galleries – with no dealer associations to co-ordinate marketing and communication. The lack of solidarity is typified by Vartai’s haughty-looking refusal to take part in Art Vilnius.

Galleries necessarily have limited budget and ambition. Promotion is flimsy, exhibition catalogues the exception not rule. Prices, by common consent, are at least 30% less than they would be in Western Europe for works of similar quality. Works offered by Temnikova & Kasela can reach €50,000, but are often nearer €5,000. Rooster Gallery of Vilnius host some outstanding young talent, but seldom sell for over €3,000. It is understandably tough for galleries to generate the finance needed to take part in international fairs and boost the value of their artists. And foreign buyers are important – accounting for between 30% and 75% of most galleries’ clientèle. It is a vicious circle.

‘Local galleries need extra help’ as Olga Temnikova puts it. Yet she has participated in nearly 40 fairs – from Miami to Istanbul – since launching her gallery five years ago. How does she do it?

Thanks largely to financial support from Enterprise Estonia (an EU-funded body for supporting entrepreneurs) – and the Estonian Culture Ministry.

I doubt such support will be available forever. It is one thing for governments to underwrite non-profit cultural initiatives – but to assist commercial entities (which is what, for all their cultural pretensions, art galleries essentially are) would appear to run counter to EU competition laws.

Most Baltic (and Eastern European) galleries are, though, able to take part only in fairs where their attendance is free or heavily subsidized – as it was until 2014 at the ViennaFair, thanks to sponsorship from Erste Bank. But relying on charity is a risky and uncertain way to establish a business along sound economic principles.

International Fairs: An Irregular Presence

It is no surprise that Baltic galleries are absent from Europe’s top three contemporary fairs (Art Basel, Frieze and FIAC) – the ones that pull in the heaviest-hitting curators and collectors.

Baltic galleries surface, instead, at a plethora of lesser fairs across Europe. As well as the ViennaFair (and its 2015 successor/competitor ViennaContemporary), these include Art Brussels, Artissima, Arco, Cosmoscow, Artmarket Budapest, Art’15, Positions Berlin and ‘satellite shows’ like Liste in Basel or YIA in Paris.

Such scattershot diversification makes it hard for galleries from the Baltic States to make a meaningful impression on the European art market. This lack of homogeneity is reflected at the Baltic States’ premier fair, Art Vilnius, launched as a perceived ‘one-off’ in 2009 (when Vilnius was European Capital of Culture), and whose continuing annual existence is something of a miracle – owing much to the skilful leadership of Diana Stomienė and Raminta Jurėnaitė.

Art Vilnius would seem to be the ideal showcase for art from the Baltic States, but no: alongside 25 galleries from Lithuania, this year’s edition featured just 3 from Latvia and none from Estonia.

If Art Vilnius is not the place to obtain a meaningful overview of art from the Baltic States, what about Vienna – which traditionally rolls out the red carpet to East European galleries? Just over one-third of exhibitors at this year’s ViennaContemporary (September 24-27) will be from Eastern Europe (34 from 99).

Alas: only two are coming from the Baltic (Temnikova and Vartai).

Events & Museums

Nor is there a big non-commercial event where international collectors can appraise the region’s art.

A ‘Baltic Biennale’ – featuring artists from all the countries around the Baltic – was held in 2008. The artists and venue (St Petersburg’s shabby Manège), however, were second division; the event had minimal impact; and was not repeated, so hardly qualifies as a biennale in the first place (which justifies Yuri Albert’s jokey conceptual assertion at the 2007 Moscow Biennale that the Baltic Biennale cannot and will not take place).

There is, though, a long-established Baltic Triennial – but it lurks so far under the radar it might as well take place on the seabed rather than inside Vilnius Contemporary Art Centre. I am still waiting for a response to my request for press information, even though the next edition opens in just over a fortnight (September 4).

National Art Gallery, Vilnius

The region’s finest contemporary art museum, and one of the most impressive in Europe, is the Kumu in Tallinn – the Baltic States’ smallest and least accessible capital. I discovered the Kumu in 2009, when it was hosting Popkunst Forever: a groundbreaking show containing the astonishing revelation that Pop Art had flourished under Brezhnev in a remote corner of the Soviet Union (Estonia). If ever an exhibition could have propelled a small country on to the global art map, this was it. I looked forward to seeing it at the Pompidou Centre, Tate Modern or MoMA. Instead, it re-emerged (heavily diluted) at the National Art Gallery in… Vilnius .

Five years later.

At least, by then, the catalogue had been published. The Vilnius National Art Gallery is one of my favourite 20th century art museums: a superb showcase for Lithuania’s rich artistic heritage. But it has no guidebook (and always seems empty, perhaps because it is too far from the city centre to attract foreign visitors).

Prizes & Curators

Olga Temnikova suggests that a lack of curators from the Baltic States on the international scene also hinders the region’s international reputation. I suspect she may be right. To take one small but telling example: the prestigious Young Curators Residency Programme, run by the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, has hosted Hungarian and Russian curators since its launch in 2007 – but none from the Baltic States.

Nor do the Baltic States possess an internationally renowned art prize, corresponding to Russia’s Kandinsky Prize or Ukraine’s Pinchuk Art Prize. Every art-lover knows Kandinsky, and most have heard of media-savvy Victor Pinchuk. But who or what were or are Köler and Purvītis – the names assigned to the national art prizes of Estonia and Latvia? *

Andris Breže

Neither prize enjoys an international reputation. When, at the 2013 ViennaFair, a minor Belgian gallery across the aisle objected to the overwhelming presence of Andris Breže’s neon-tubed White Square, it was promptly removed to an obscure corner of the VIP Lounge – even though Breže had been short-listed for that year’s Purvītis Prize.

Lithuania lacks an art prize, although it plays host to the Jaunojo Tapytojo Prizas (Young Painter Prize), open to artists from throughout the Baltic States (this Baltic solidarity does not extend to the award’s website, which is in English and Lithuanian only).

* Answer: each country’s ‘National Artist’ – Johann Köler (1826-99) and Vilhelms Purvītis (1872-1945). Both studied at the Imperial (now Repin) Academy in St Petersburg, where Köler spent most of his adult life; Purvītis returned to Riga to found the Latvian Academy of Art. Estonia’s prize might be better known if it had been named after the great Non-Conformist Ülo Sooster. If Lithuania ever launches one, the name of Mikalojus Čiurlionis springs to mind.

Riga Falls Short

The art market in the Baltic States would surely benefit from having a focal-point. As the region’s largest city, Riga should be the power-house fuelling that market – especially as it is the region’s only city accessible from all Western Europe’s major hubs (London, Paris, Zurich, Frankfurt, Amsterdam) without changing planes (Vilnius, despite hosting an international fair, has no direct flights from Paris or Switzerland). But the Latvian economy is weaker than that of its two neighbours – its GDP has still not returned to 2008 levels – and, although Riga is the third-largest city on the Baltic (behind St Petersburg and Stockholm), its population of 640,000 makes it only the 60th largest city in Europe.

Project by Rem Koolhas

What’s more, Riga lacks a major contemporary art museum. Grandiose plans by Rem Koolhas to create one by transforming the Andrejsala power-plant, announced in 2006, have gone nowhere. The embryonic Art Riga fair has yet to rise beyond the small and quirky, while Rīgas Galerija – for many years the city’s most high-profile – now operates by appointment-only from a private flat, after being forced to abandon its spacious, city-centre premises in a wing of the Riga Hotel.

A Problem Of Image

The Baltic States are not helped, either, by their nebulous public image. Whatever their manifold attractions, the three countries are not prime tourist destinations. Many Westerners confuse Lithuania and Latvia (in French, Lituanie and Lettonie sound virtually identical), and would struggle to place Estonia on the map.

The term ‘Baltic States’ is misleading (there are actually ten of them) and implies a homogeneity that does not exist: Riga and Tallinn grew up as Hanseatic towns with a strong Germanic influence (Lutheranism remains the dominant religion to this day); Lithuania, on the other hand, was long welded to Poland (sharing its Catholic faith), and extended as far south as Moldova before coming under Russian sway a century later than Estonia and Latvia.

The three States should do more to stress their individuality – but this depends essentially on government efforts in the fields of tourism and culture. Other countries often referred to as a group, such as those of Scandinavia or the Southern Caucasus (Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan), have far stronger individual identities.

All three Baltic States retain a border with Russia, and the Soviet occupation they endured between 1944 and 1991 retains a pernicious influence. Visitors to country pavilions at this year’s Venice Biennale will get the impression that the Baltic States have yet to escape from their Communist bondage. Jannus Samma (Estonia), in A Chairman’s Tale, charts the Soviet career of a sleazy homosexual; a multimedia installation called Armpit (Latvia) is ‘reminiscent of a spaceship built according to the aesthetics of Soviet garage co-operatives’; and Dainius Liškevičius (Lithuania) has created a ‘fictional museum that takes us back to the recent Soviet past.’

Artists from the Baltic States should give shorter shrift to the arcane delights of Conceptualism – and look forward, outward and away from Russia. Riga and Tallinn, after all, are a short ferry-trip from Stockholm and Helsinki respectively. Although Lithuania has been virtually landlocked for most of its history, acquiring a seaport (Klaipeda) only in 1923, it was traditionally anchored in Central Europe – once flanked by Germany and Poland rather than two Cold War leftovers (Kaliningrad and Belarus).

Western Ignorance

The Baltic States suffer both from the stigma of having been part of the USSR for much of the 20th century, and from Western prejudice against Eastern Europe in general. Such ignorance is not confined to the general public. When I encountered Tate Modern’s Russian & Eastern European Acquisitions Committee in Moscow in 2013, during their whistle-stop tour of some of the 20 or so capitals under their regional remit, hardly any of its members seemed to have much clue about art from behind the former Iron Curtain.

It is surely no coincidence that the only two galleries from Eastern Europe to have taken part in both Frieze and Art Basel, Gregor Podnar (Ljubljana) and Plan B (Cluj), were selected only after re-locating to Berlin, thereby gaining superficial credibility in the supercilious eyes of the Western art-world.

Plan B is something of a rôle model for East European galleries. It launched (and was co-founded by) the East European artist currently highest in the ArtPrice rankings: Adrian Ghenie (123rd).

Ghenie has had shows at Pace and Haunch of Venison, and is one of the few East European artists to have been exhibited by François Pinault in Venice (along with Poland’s Piotr Uklański, who is represented by Gagosian).

If the Romanian art market can throw up a figure able to wow the Western art-world, surely the Baltic States can, too. After all, they’re wealthier. In terms of GDP per capita, Estonia ranks 25th in Europe, Lithuania 28th and Latvia 30th. Romania is 32nd.

Or Do The Baltic States More Than Hold Their Own?

It could, though, be argued that Baltic Art punches above its weight. We are talking about three very small countries: Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia rank 35th, 39th and 41st in Europe by population. Even if the Baltic States were considered a single unit, they would still – with a total population of 6.2 million – rank only 25th.

Only one ex-USSR country has a higher art-world profile than that of the Baltic States: Azerbaijan, whose Baku-based Yarat Foundation, run (admittedly with taste and flair) by a member of the country’s ruling family, has burst on to the scene with access to extensive funding not bereft of ulterior political motive (‘caviar diplomacy’ as The Guardian puts it). The prospect of such largesse becoming available in a Baltic democracy is unlikely, and probably undesirable.

There may be no artists from the Baltic States in the ArtPrice Top 500 – but there are none from Finland either, whose GDP is two and a half times higher than that of the Baltic States combined. The presence of galleries from the Baltic States in fairs across Europe matches, if not outstrips, that of Scandinavian galleries.

There were only two galleries at this year’s Art Basel from the whole of Eastern Europe: Foksal and Starmach, both of Poland, whose GDP is five times higher (and population six times bigger) than that of the Baltic States. But there was at least some Baltic presence in Basel this June, albeit at satellite shows: Estonian gallery Temnikova & Kasela at Liste, and Bastejs from Riga at Scope.

Still, that presence was twice as strong as Russia’s (just Triomf Gallery, at Scope).

Compared to other former Iron Curtain countries, whose art markets also started from scratch in 1991, the Baltic States perhaps lag behind Poland and Hungary – but outperform Bulgaria and Serbia, each of whom has a larger population than Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia combined.

Looking Ahead, Patiently

To promote the art of the Baltic States one might, with some wishful thinking, envisage a Nordic Art Fair hosting countries from both sides of the Baltic, held alternately in Riga and Stockholm; and the staging of a symposium to explain to an international audience the difficulties, attributes and potential of the artists and art market in the Baltic States (if not Eastern Europe as whole).

The Baltic States already host one of Europe’s finest art websites (trilingual to boot) – although the region’s art trade might benefit if it contained more information on galleries, and the excellent value of the works they offer.

A Baltic-wide art prize might generate useful publicity – although funding it would be one problem, the choice of name another. And you can imagine the political outcry if one of the three States went four or five years without providing the winner.

Perhaps more Baltic dealers should follow the example of Jurgita Juospaitytė-Bitinienė, owner of Rooster Gallery in Vilnius, who scours the internet for news of international art awards.

Eglė Karpavičiūtė

Her young artist Eglė Karpavičiūtė (born 1984) was a finalist in the 2011 Sovereign European Art Prize and, this Summer, won two Italian awards: the Premio Combat Prize and the Donkey Art Prize. Her work will, as a result, be exhibited in Milan, Miami, Tokyo and Dubai in the second half of 2015.

The Figurative art in which the Baltic States excel may be not conform to current Western taste – yet fashions come and go. Quality is eternal.

As Astrīda Riņķe observed, there is no shortage of regional talent, for whom international fame ‘is primarily a question of time.’

Yes, but. In today’s fast-moving art-world, patience is in short supply.

Time and the Baltic tide wait for no man.