No pain, no gain

An interview with Polish artist Wilhelm Sasnal

21/12/2016

The works of Polish artist Wilhelm Sasnal are inspired by daily life. He interprets reality personally, sometimes even very much so, when creating his paintings, comics and films; his works are characterized by a free intermingling of styles and methods of expression, yet he stays faithful to traditional forms of expression – oil on canvas for painting, and a film camera for video works. In other interview, Sasnal once called himself a “realist painter” precisely because the roots of everything that he creates can be found in personal experience, images found on the internet, books, or music. All of his works are enveloped by a feeling of powerful personal memories and history. The subjects are things that are important for Sasnal to speak about.

Wilhelm Sasnal studied architecture at the Kraków University of Technology (1992–1994), and fine-art painting at the Krakow Art Academy (1994-1999). During his student years he was known as an activist for the Krakow artist group Ładnie (1996–2001), who were in opposition to the Art Academy. Sasnal was also recognized by the Polish art community, having won the Grand Prix at the 1999 Bielska Jesień fine-art painting biennial; but just a few years later, he was already making his mark on the international art scene. After exhibiting works at Art Basel in 2002, Sasnal began participating in notable international art exhibitions such as Urgent Painting (Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, France), and Painting on the Move (Kunsthalle Basel); in 2005, his work was shown in the Triumph of Painting exhibition featuring Charles Saatchi’s collection. After this exhibition, the Saatchi Collection put up Sasnal’s painting “Samoloty”/“Airplanes” (1999) for auction, at Christie’s in New York; it fetched $396 000, the largest sum ever paid for a work of Polish contemporary art. A year later, in the magazine Flash Art’s list of 100 best new artists, Sasnal was listed as number one.

Wilhelm Sasnal. Samoloty, 1999. Oil on canvas. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Sasnal is currently working with such world-class galleries as Hauser & Wirth in Zurich, Anton Kern Gallery in New York, Sadie Coles in London, and Foksal Gallery Foundation in Warsaw – it was at Foksal’s booth at Art Basel 2000 where Sasnal’s rise to stardom began.

Although he is best known as a painter, Wilhelm Sasnal together with his wife Anka made several films. This last August saw the premiere of the feature-length film “The Sun, the Sun Blinded Me”. The film was inspired by Albert Camus’ novel “The Stranger”, and tells of the reality of today’s Poland. Touched upon in the film is the subject of immigrants – a theme that peaked in Europe during the making of the film, and one which the filmmakers couldn’t even imagine when they came up with the idea for the film four years ago.

I met with Wilhelm Sasnal at the beginning of summer in Krakow. Sitting on a park bench in the center of the city, we spoke about how painting differs from photography, about turning points in his career, and what issues he is currently worried about.

Trailer of The Sun, the Sun blinded me

You are inspired by everyday life; your themes are chosen on the basis of an attentive observation of your surroundings. Could you tell me about the process – how does an artwork start for you?

I draw a lot, I make sketches in my sketchbook. On my computer I have a folder where I put photographs that I might use – these are both the photographs that I take with my phone, and found images on the Internet. Sometimes I cut out some pictures from the newspapers and glue them into the sketchbook. Usually, before starting to work on a painting, I already have an idea about the size of it. I make a grid on a printed out photograph or sketch, I draw it on a canvas, and then I start painting. It works more or less this way. I never lack for images, there are so many of them. For instance, this week I chose a sketch that was very quick and quite random. I drew it three months ago, during the winter holidays – my son is in it, and I like it very much. There was something very unique about it, though it was quite scruffy; it wasn’t a really profound sketch. Even with this one, I made a grid and I tried to put the sketch onto the canvas. Although I make a grid and I draw, very often I don’t know what the outcome is going to be because I change a lot during the process. I don’t like paintings that give you an impression that they have been made like this [snaps his fingers]. Those I regard more or less as design. You have to really put quite an effort into it. I mean – no pain, no gain.

Could one say that you are interested in the possibilities of representation, and in examining the processes of seeing and perceiving?

Rather – in the process of painting. I don’t know… they are probably the same. Maybe not, but they are very similar. I like works were you can see – OK, this thing has been made this way. On the other hand, I also believe that I’m interested in a sort of magic (I know that’s a heavy word) or mystery. This is what attracts me. Something that you don’t know exactly, something that is ambiguous in the work. So, maybe not seeing but perceiving things – perceiving in a quite broad sense, not only on the visual level – how we read or how we approach the history and so on.

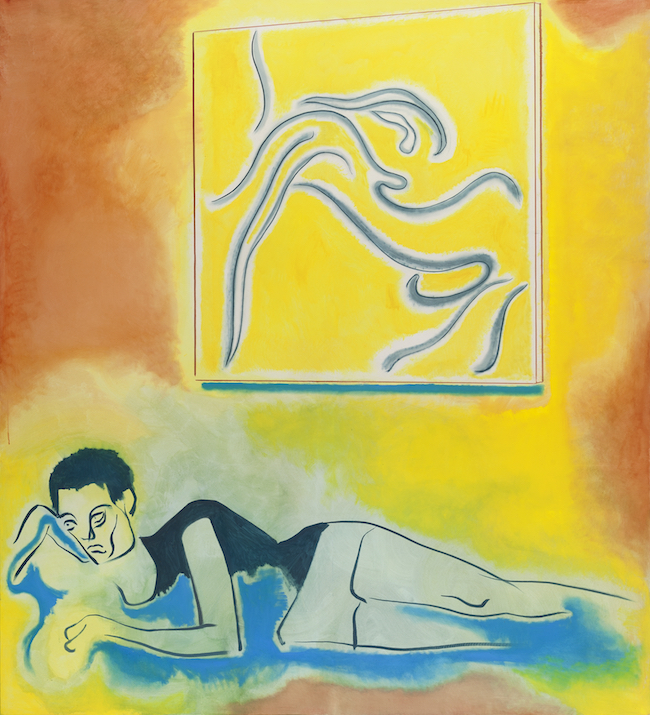

Wilhelm Sasnal. Kacper, 2016. Oil on canvas, 220 x 200 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The Internet and digital technologies have influenced not just image aesthetics alone, but also the ways we perceive, create and share images. The image has acquired more significance than ever before. How do you see the role and power of an image today?

This is something very disturbing because there is an avalanche of images and verbal information in our everyday lives; however, there is an opportunity there for fine-art painting because it is a sort of means with which to bring up certain issues in terms of imagery. When you look at the images in the newspaper, in any advertisement, prints etc. – as they are so many, they are devalued; they also don’t have value in terms of conveying certain issues or topics as compared to paintings. A painting is not an image; a painting is something else – because of the time that you need to execute the painting, and also because the painting is hand-made as a coherence of thoughts, the body, the hands, the eye. It is a much more complex piece, and that’s why you can read it on many levels.

But photography can also be multilayered.

It definitely can, I’m not denying that. I am not trying to say that it is worse or better, however, it is different. What is very important in terms of painting or drawing – there is this natural and nearly animalistic way of communication. This is why it is different.

.jpg)

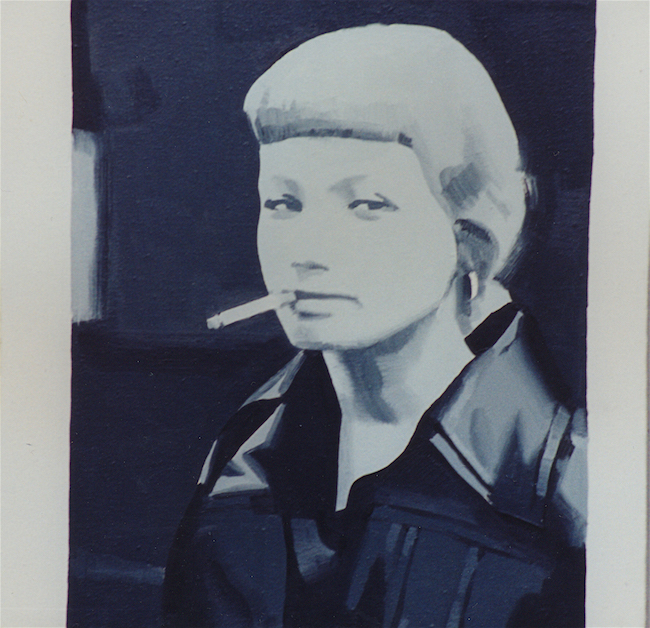

Wilhelm Sasnal. Martyna, 2001. Oil on canvas, 60 x 70 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

What are the best working conditions for you? Do you need silence when you paint, or do you need music...

No, I don’t need silence, and this is why I like this job a lot – I can listen to music and have people around while I’m painting. Of course, there are only a few people who are allowed into my studio, like my assistant or my family. Very often I have to look after my daughter, so she spends the whole day in the studio, and I like it, I can talk to her... Now I am preparing a comic book, and it is a bit different – I can’t listen to music, I can’t become focused on any words coming from the outside. But with a painting, you can just keep on painting and listening to music.

What do you listen to at those times?

Lots of radio; I like classical music, but also a lot of guitar music from the late 1990s to 2000, a lot of shoe-gazing music. There are several bands that I always come back to.

Wilhelm Sasnal. Dominika, 2001. Oil on canvas, 33 x 33 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

If we go back to painting, as long as I can remember, there has always been a discussion about the future of painting – is it alive or is it dead...is painting experiencing a renaissance...and so on. How do you see the role of painting in contemporary art today?

Of course, these discussions began when photography came into existence, but I don’t think there’s a revival or a decline. I don’t think that something like “the death of painting” will happen. Of course, painting is a little bit obsolete because it is an activity loaded with tradition. I’m also in the film field, and I can see how these two disciplines interfere, how they work together, and how important painting is to filmmakers. OK, to some clever film makers. [Smiles.] I don’t think we are in any specific period right now. I would even say that we aren’t in a special period in terms of art. However, this is a very special period in terms of politics and society, and this is what bothers me. What is going on right now is so scary. Art is not essential; it is not necessary for life.

What is it that bothers you?

I mean everything! In Poland, and also in Europe. I’m such a believer, an enthusiast of Europe. The Polish shit – that’s the worst! The Polish nation – now you can touch it, you can smell it, and I’m scared; I’m fed up. I thought that the great time for us had come because we would be back inside of Europe, that we could really change...there hadn’t been such a period of Polish prosperity since the late Renaissance – and now everything is getting dismantled.

Wilhelm Sasnal. Bez tytułu (Church), 2001. Oil on canvas, 120 x 110 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Are you talking about the governmental changes in Poland, in which the right-wing national-conservative political party came to power?

Yes, mostly because of that, but of course, the government emanates from society. This is what we have – our society is in such a poor intellectual state.

Will your comic book be about these issues?

In a way. It will refer to the past, and it will stop at the moment when my parents met. There are certain facts about my family that I know – some of them are not probably real (they are more like family legends), but some are real. I have to fill the gaps with sort of made-up patches. And I don’t see much difference between history and the present. I think there is continuity, and what happened then has influence on today. This is something that is not over; we are not cut off from the past. What we do know, what we miss, what we are happy with – to a certain degree, it is influenced by history – our big history and our small, personal histories.

_2003.jpg)

Wilhelm Sasnal. Shoah (Forest), 2003. Oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

I’ve been told that in Poland there is one discussion that never ends, which is always on people’s minds – even during parties, sooner or later people start to talk about it – and that is the Holocaust. And you also talk about that in your pictures.

Yes, you cannot be indifferent to the fact that before the war, the biggest Jewish population in the world used to live here – over 3 million people. It is not like putting the blame on somebody, but we have to reconsider our participation in it – what we have done, what my grandparents did to act against it. Were they just silent witnesses, or did they do more. Auschwitz is 50 kilometers from Krakow, so you can’t forget about it, but I’m afraid that, in a way, it can be a little bit in fashion now among the young intelligentsia to have these kind of discussions. However, I still rediscover certain facts about the Holocaust, and at least for myself, I have defined the relationship to the past – victimization, and being on the other side. I’m fine with this now, but in the beginning it wasn’t that easy – everything was just so shocking. So, maybe that’s why I can even be critical or suspicious when some people just keep playing this Holocaust card superficially. Anyway, it is a real subject today; at least antisemitism is – that is not over. It is so very present. You’ve probably seen the graffiti in the city – Stars of David crossed out. This is not only about antisemitism, it is also about the anti-immigrant movement. I think they both are rooted in Polish national-Catholicism. This is the worst. And this is what is prevailing now.

Wilhelm Sasnal. UN, 2015. Oil on canvas, 160 x 220 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

If we talk about world globalization and art – is it important to conserve a national feeling in art?

Of course not! I would be the last person who would support the memorializing of national ideas in art. I think it is very important for myself, but it should not be forced upon us by the government. I hate this word narodowe (‘National’ in Polish), which also alludes to a kind of exclusiveness – that you have white skin and so on. We are not living in the 19th century anymore... However, I think it is important to find your identity. But that is only my attitude towards it. If you feel more like a citizen of the world, then you don’t need it. Regarding myself – I need it at least to a certain degree: to acknowledge where I am from, why I am here, what does that mean, what is the history that my decedents took part in.

You are internationally well known; is it important for you that you are considered a Polish artist?

This is different. Being regarded as Polish or being from Poland is important. I consider myself as being from Poland. Although, according to the right-wingers, I am anti-Polish. I am a sort of self-hating Pole. [Smiles] Even though my wife and I tried to live abroad several times, we always came back because we missed this place. On the other hand, I would die if I were forced to live here for good. This is a very ambivalent feeling. I love it and I hate it – I like the country, the landscape, I like the smell, etc., but on the other hand, I hate so many things.

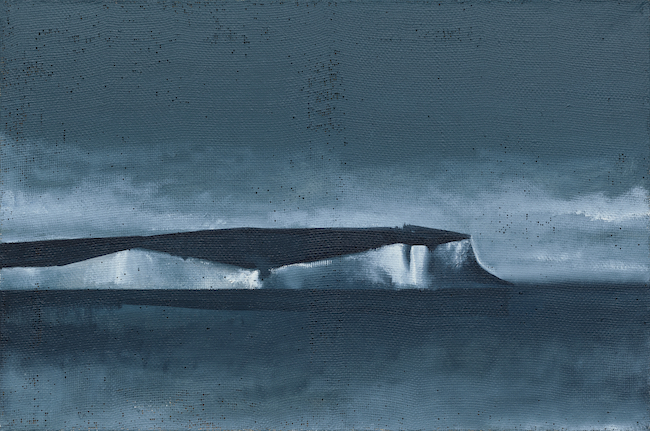

Wilhelm Sasnal. Dover, 2016. Oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Let’s talk about your artistic career. As an artist from a small town in Poland, you have, nevertheless, managed to climb to the top ranks of the world’s best artists. What do you consider as a turning point in your career?

It was in 2002 – I took part in the exhibition Urgent Painting in Paris, and then – Painting on the Move in Basel. But it all started with the Art Basel fair. There I met the galleries that I work with now. Fortunately, I was quite away from all of it when it happened – I didn’t even live in Krakow at the time, but in a small town near Krakow. The “success” seemed to be somewhere else because I just lived my everyday life, I painted and so on. So it was easy to digest it. Today I feel very secure, and that is important, but I always have this feeling – the bigger the success, the bigger the possibility of losing it all.

Wilhelm Sasnal. Anka, 2001. Oil on canvas, 45 x 50 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

So it wasn’t as if you were struggling for that success – it felt as if it was just a stroke of luck for you.

At the time when we – my generation – were students, the notion of success didn’t exist. We started in the early 90s, when no one around here had any so-called success; very few people could make a living by doing art. We knew that if we could be one of those lucky ones, that that in itself would be great. We never made anything on purpose, just to accomplish it. It just happened. You can’t control it; this is the trick, I think. You cannot plan your success.

But you need something behind it all. Perhaps a passion for the thing that you are doing?

The point is – be truthful, be reliable to yourself. Once you trick yourself, once you lie to yourself – it doesn’t work anymore. If you want to say or to show something to people, you can’t think that it is crap. You have to really know that this is something valuable – don’t just give people a piece of shit.

I am also a big believer in labor. This is what I belong to. I work a lot, and I think that the work is what gives it value. I hate the notion of an artist being totally isolated and living in his or her own world, in solitude, and he or she has one idea once a week, and makes great art. This is bullshit. I’m not saying that the artist has to make political works, but at least he or she has to have an opinion, and has to be active as a citizen.

Was it Foksal Gallery that brought your works to Art Basel in 2002? How did you start working with them?

The artist Grzegorz Sztwiertnia – he used to go to school with Andrzej Przywara (the Head of Foksal Gallery by then) – told me to take my portfolio and go to Warsaw, and to show it to Andrzej, as he had mentioned me to him. So I did. That was in 1997. They were very supportive, and they actually showed me a lot of contemporary art I had not seen before. At that time, my knowledge about art ended with the early 90s. And most of the contemporary art I saw was brought to me through music – album covers, images that related to the music, etc. The Foksal Gallery people showed me art that was very important to me because it was also about my life – for instance, the works of René Daniëls, Mike Kelley, Raymond Pettibon.

_2001.jpg)

Wilhelm Sasnal. Untitled (Athletes) 1, 2001. Oil on canvas, 25 x 21 cm. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Is there anything else that you would like to say, but I didn’t ask you about? What do you expect from interviews before you give them?

I like to answer questions and develop answers, because this is how I also learn about myself and my approach to art. It is important for me to put into words what it is that I do, in order to understand it. Of course, you don’t have to understand everything you do – it could be bad to understand everything – but it is nice to understand at least a part of it.

Material produced with the support of Adam Mickiewicz Institute