In the footsteps of lost time. Jan Fabre

Ecstasy & Oracles, Jan Fabre’s exhibition in Sicily

30/07/2018

‘Only horoscopes are not always accurate, and the necessity, when judging a work of art, of including the temporal factor in the sum total of its beauty introduces into our judgment something as problematic, and consequently as barren of true interest [...]’

For quite some time now, this quote from In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, the second volume of Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time, has settled in the depths of my consciousness. Recently it has been ‘popping up’ again as I ponder the latest exhibition by Flemish artist Jan Fabre, Ecstasy & Oracles, which has been on view in the Sicilian cities of Monreale and Agrigento since July 6 and will last through November 4. Although the exhibition has not been created within a context pertaining to either Proust or the stream-of-conciousness style popular at the turn of the 19th century, many of its associated factors do bring to mind both the autonomous beauty of a work of art and the influence of time (in terms of material existence and the surrounding circumstances) on the viewer’s sense of perception. I must note here that I came to this conclusion only several days later, upon my return to Riga: partly due to the rather chaotic organisation of the exhibition (which, of course, made for chaotic thoughts on what one had just witnessed), and partly due to the fact that my true memories of what I had experienced didn’t fit all that easily with the narrative that Fabre’s art had invoked. And so I shall start things off with a short discourse on Sicily and the peripheries of Italian culture.

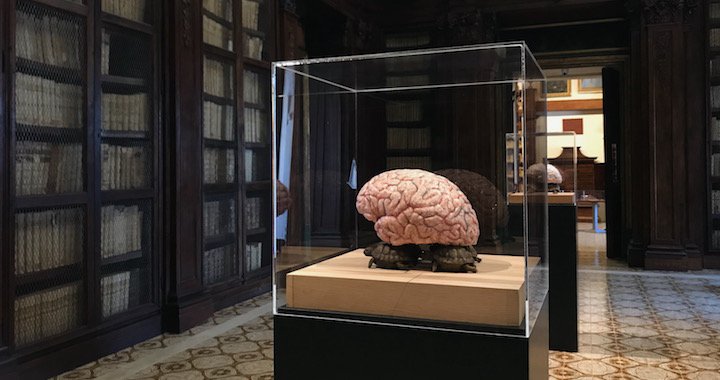

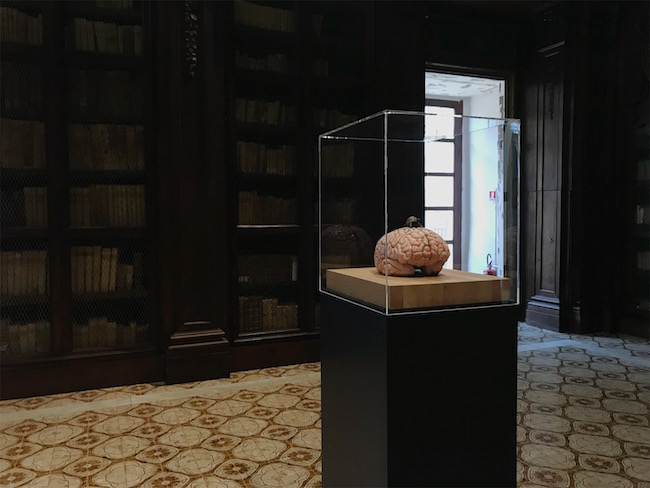

Biblioteca Lucchesiana

Santa Maria Nuova Cloister of the Cathedral of Monreale. Exposition view

The fact that Fabre is an artist of such caliber that his works are shown throughout the world (he is currently participating in seven exhibitions in eight different European locations) notwithstanding, his appearance on the Sicilian scene may seem a bit perplexing. Italy’s southern region (aka ‘the front tip of the boot’) is replete with verdant flora and a rich historical and architectural inheritance; it was also once home to the travelling troubadours of the Middle Ages and, a few centuries later, to many writers of 20th-century classical Italian literature. In the context of European and even Italian art, however, one rarely hears about the visual art of Sicily. To the joy of modern-art haters everywhere, when l’arte italiana is mentioned, it is usually taken to mean the works of the Renaissance masters. In emphasising the values of Renaissance Humanism, phenomena such as the Arte Povera movement and the politically and socially satirical works of Maurizio Cattelan and Fiorella Mancini are seemingly forgotten. The Venice Biennale, the Milan Triennial and other contemporary art happenings don’t lose their meaning, yet they are unable to compete with the Rinascimento. We seemingly forget that the ‘one-man band’/‘jack of all trades’ phenomenon, which grew alongside the Renaissance, hasn’t gone anywhere.

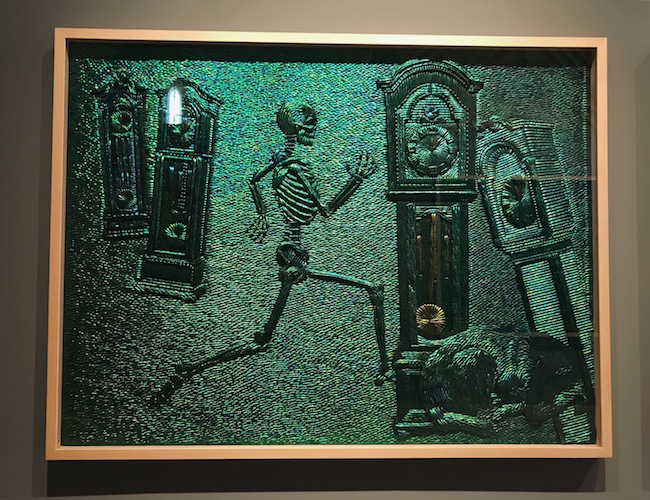

Searching for Utopia II (running wild), 2005

One should feel no shame in resting on one’s laurels, especially if those laurels were earned by such eminences as Leonardo da Vinci and Dante. Nevertheless, they can become a bit burdensome and, occasionally, even morph into stereotypes. To counter this, since 2015 the Italian Culture Ministry has been selecting a yearly Italian Capital of Culture, with the goal of encouraging and bringing attention to the art and culture of 20 different regions of the country. This year’s Italian Capital of Culture is Palermo, which is also concurrently hosting Manifesta 12, Europe’s only nomadic art biennial. Having always had a focus on social issues, this year’s Manifesta is featuring two topical subjects – climate change and migration, and how they affect Palermo on a daily basis. Titled The Planetary Garden. Cultivating Coexistence, the exhibition programme is being presented at twenty different venues throughout the city, and also encompasses a number of collaborative projects, including Jan Fabre’s Ecstasy & Oracles.

Oracle Stones in the Hour Blue, 1989

As mentioned above, Fabre and the show’s curators, Joanna de Vos and Melania Rossi, have chosen two wonderful Sicilian cities and several historically notable locations in them as venues for presenting the artworks. Ecstasy & Oracles consists of about 50 works consisting of several series created by Fabre from 1982 to 2018, and which reflect the artist’s quintessential symbols of eternity and time. Spanning from the early 1980s, with readymade aesthetic objects from the series Thinking Model (1983) and the fascinating blue ballpoint-pen drawings from the series Oracle Stones in the Hour Blue (1989), to very recent object and sculpture series, the exhibition presents a truly broad look at the transcendental art world of the Flemish artist. Nevertheless, no matter how affecting the works of a renown, world-famous artist may seem, an ambiguous exhibition format can quickly degrade the viewer’s impressions when they see the works ‘in the flesh’. In this case, the ambiguous context has greatly muddied the viewer’s experience with Jan Fabre/his works. In the exhibition description written by the show’s curators (which was sent out only to member of the press, and is inaccessible to ‘regular visitors’), they stress Fabre’s interest in living creatures, mythology, the environment, and the relationships that the artist has with them. Especially emphasised are the image of the turtle and the meaning of the scarab in Fabre’s creative research and works. And the exhibition does, indeed, reflect how this preoccupation with in-depth analysis and representation of certain characters/figures has developed over the years.

Holy Dung Beetle with walking stick, 2012

Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas, 2016

The man who bears the cross, 2015

Three silicon bronze scarabs have moved into the Santa Maria Nuova Cloister of the Cathedral of Monreale: Holy dung beetle (2011) – the bearer of the cross ; Holy dung beetle with walking stick (2012), and Holy dung beetle with laurel tree (2012). Although they have been placed upon pedestals, they look like authentic holy objects one would find in a church. Behind them is a room containing the ‘scarab paintings’ from the series Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas (2016); it is, unfortunately, difficult to immerse oneself in their study when placed in such a long and narrow space. Undeniably, the most brilliant part of the Monreale exhibition is the sculpture The man who bears the cross (2015), which is hidden away in an inner room of the fascinating Byzantine-style cathedral. Standing out from the multi-coloured background, it attracts viewers like a magnet.

Hand holder for the silver cabinet, 1978-79

In the part of the exhibition located in Agrigento, the image of the turtle dominates. Although the greater part of the exhibition (size-wise) is presented in the Greek-built Valley of the Temples Archaeological Area (featuring several silicon bronze sculptures and outdoor video screens – including the 2018 performance Schande übers ganze Erdenreich! (Shame on all the Earth!), and Fabre’s drawings), more emotionally surprising is the part of the exhibition located in the Lucchesiana Library (featuring Hand holder for the silver cabinet [1978-79]; Turtle in unknown country [2014]; Four oracle stones carry an unknown planet [2008]; and The universe carried by a tortoise [2014]). This ancient book repository, founded in 1765, has remained virtually untouched, and reflects the ‘loss of time’ principle intrinsic to Fabre’s ‘turtles’.

The man who bears the cross, 2015

The man who conducts the stars, 2015

Jan Fabre’s creative and conceptual capacity is undeniably influential – it is not for naught that he is often referred to as ‘a Renaissance man’. As the philosophical and historical message connects with contemporary interpretations, the art of the Flemish artist becomes an acknowledgment of the infinite. However, returning to the Proust quote, the question of the intrinsic value of the work of art (the artist), independent of the curator’s intentions or the placement of the exhibition in specific space, becomes relevant. Ecstasy & Oracles is an exhibition that can be viewed, evaluated and understood in two ways (much as Italy’s culture and artistic legacy are): first of all, it is the presence of Jan Fabre in two Sicilian cities; only secondly is it an exhibition as an assemblage of ideas. By choosing to classify the figures in the artworks (scarabs and turtles) by adapting them to two different cities, the curators have created a ‘break’ – a physical and conceptual division – in the exhibition, which prohibits one from seeing the event as a mutually connected whole. The result is two separate exhibitions that happen to feature the works of Jan Fabre.

Valley of the Temples. Exposition view

Valley of the Temples. Exposition view

This is especially palpable in the Valley of the Temples, where the viewing of Fabre’s works turns into something of a hunt (or even a game of hide-and-seek): visitors are not provided with a map indicating where the works are located, nor are they given an informational handout – all of which makes the whole process quite difficult. Only adding suspicion is the fact that the employees at all of the exhibition venues are woefully uninformed of the exhibition, and when the ticket collector asks us how to correctly pronounce the name of the artist, it becomes clear that a status of ‘prestigious happening’ has been given to the event by us – those who are linked to the exhibition only indirectly. In the end, it turns out that the factor of time, which has been ‘mixed into’ art, is Fabre, who, in turn, has been ‘mixed into’ the accumulated wealth of Italian art. An evaluation of the exhibition becomes linked to its environment – even to the point of being inseparable from it. A bold environment only plays with art, and ends up transforming ecstasy into perplexity.

The loyal scavengers, 2016

The man who gives a light, 2002

Schande übers ganze Erdenreich! (Shame on all the Earth!), 2018

Yo he ilegado antes, 1990

Loyalty keeping watch over time and death III , 2016