A Unique Treasure Trove of Art in India

23/01/2014

Photo:

400,000 visitors in three months – just 60,000 less than the Venice Biennale received in over half a year. Those are the stats for India's first contemporary art biennale (the Kochi-Muziris Biennale), which took place two years ago. Those are impressive numbers when one takes into account that most people still associate India with things like complex-ridden Westerners searching for their spiritual true-selves, the beaches of Goa, the dreadful scenes from “Slum Dog Millionaire”, and the Taj Mahal – but definitely not as a destination for contemporary art tourism.

Enough of that! Despite all of the preconceptions and stereotypes, all signs indicate that the Kochi-Muziris Biennale has, at break-neck speed, acquired the status of a must-visit art happening. If at the first Biennale there were 80 artists participating from 24 countries, than this year, in its second incarnation, there are 94 artists from 30 countries around the world participating. If the “list of stars” for the first Biennale included the Indian contemporary art superstar Subodh Gupta, the Brazilian Ernesto Neto, and the scandalous Chinese dissident Ai Wei Wei, then this year, along with many well-known Indian artists, we can see Martin Creed, Wim Delvoye, Mona Hatoum and Yoko Ono, as well as the most famous Indian on the word's art scene, the London-based Anish Kapoor – who is also one of the most ardent supporters of the Biennale. Tate Modern director Chris Dercon, who was seen at both this year's and the previous Biennale, stated in an interview that the “Kochi-Muziris Biennale is able to re-define, re-evaluate and to bring into shape again the life of Biennales in general.” Around Christmastime, Okwui Enwezor, the curator of this year's Venice Biennale and the director of Munich's Haus der Kunst, was seen to be taking a keen interest in the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (perhaps searching for inspiration?), as well as giving a lecture there.

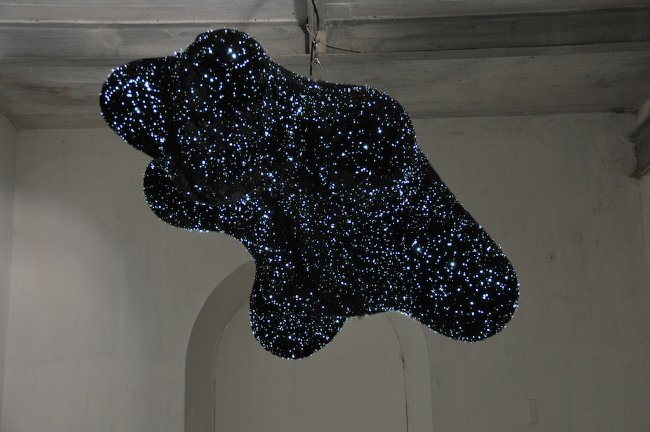

Indian artist Bharti Kher's "Three Decimal Points/Of a Minute/Of a Second/Of a Degree" (2014)

And it isn't just the exotic location (and the chance to enjoy some sunshine at a time when Europe is drowning in snow and sleet) that is currently drawing Europe's artistic elite to India. In a certain sense, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is a wholly extraordinary precedent. It differs from other similar events in the world with the defining feature of its creators and organizers being themselves artists. The Biennale is the brainchild of two Kerala-born, now Mumbai-based artists – Bose Krishmamachari and Riyas Komu. It is an ambitious project begun four years ago, and can literally be called a passionate and, in a sense, fanatical initiative. Especially taking into account the fact that it takes place in such an unpredictable place as India. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale came about as an alternative to the decidedly commercialized Indian art scene in which, at least up till now, non-profit art events have been uncharacteristic.

It goes without saying that the Biennale has struggled with chronic lack of financing since the start, even going so far as to threaten the realization of the concept planned for its opening day. The huge amount of international press coverage on the first Biennale notwithstanding, the same financial problems were faced again this year. In India, philanthropy is still in its infancy, and support of the arts is not in fashion here, at least not now. In addition, those who are in a position to help are confounded by the seemingly surreal fact that nothing at the Biennale is sold, and that everything is publicly accessible. The Biennale is partly supported by the state, but both times now its pledges have far outweighed actual disbursements. Understandably, the priorities are elsewhere for a country in which the large majority of its inhabitants live under the poverty line. A partnership between the state and the public is being discussed as the ideal solution for the future, but while this has yet to reach optimal implementation, a part of the Biennale is supported by the artists themselves. Many of them have self-funded the creation of their works, fully realizing that they may not get a return on their investment.

And no matter how utopian it may sound to the absurdly bloated Western art world, perhaps it is precisely this lack of financing and its associated uncertainties that are the main strength of the Indian Biennale. In essence, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is a kind of artist holiday for the artists themselves, and from this aspect, it is an absolute one-of-a-kind in terms of all creative forms of expression.

Graffiti on the streets of Kochi

Undoubtedly, one of the Biennale's trump cards is its location – the harbor city of Kochi, a onetime stop on the legendary Spice Route in the Indian state of Karela. Located in the south of the country, Karela distinguishes itself from other states by having the highest literacy rate in India – more than 90% of its inhabitants have been educated. This is also where 90% of the world's spices are grown, considered the “gold” of this part of India. The Arabs were the first to discover this treasure trove, to be followed by the Romans, Egyptians, Chinese, Portuguese, French, Danish and Brits. All of them took a turn at mucking about the coast of Karela in their forays for spices. The story of the ancient Spice Route is not, however, only about successful economic enterprise and the transport of “gold” to the royal courts of far-off lands; it is also a story about movement, discoveries, adventures, migration and merging. The Spice Route changed maps; it discovered new continents and new shipping routes, forever changing the rhythm and habits of life in its major stop-off points. One could say that it was a forerunner of the globalization to come. While traders left India with peppercorns, the Arabs brought coffee to India (which is now grown in plantations in Karela's neighboring state of Karnataka), the Portuguese brought vinegar, the Dutch brought potatoes, and so forth. In the golden years of the Spice Route, goods (including elephants and rhinos) were transported from the harbor of Kochi to Alexandria, then on to Rome. All of the larger religions – Christianity, Islam, Judaism – came to India's shores, and there they still live on today.

Being a crossroads of both shipping and spice routes, in the 15th century Kochi was also an epicenter of many new discoveries – the city also had well-known schools of mathematics and astronomy. If the first Biennale was a kind of “warm-up” – a dedication to the city's past, then the latest incarnation is substantially more conceptual and with a more ambitious scope. Its title: “Whorled Explorations”, is a phonetic play upon the words “world” and “whorled”, and the Biennale itself can be symbolically compared to the instrument that an investigator of the stars is never without – a telescope. The Biennale is a story about the process of discovery, as its curator, Jitish Kallat, attempts to conjure up the feelings experienced by the ancient seafarers and star gazers, carrying them over to today by offering visitors an artistic science fiction journey into the depths of the Earth, the Universe, and our personal existence. From cartography to ecology, from migration and international conflicts to the limits of human perception and abilities. And it must be said that it is hard to imagine a more ideal and organic stage than Kochi for the inception of this concept. The architecture in Kochi's oldest neighborhood, Fort Kochi, is still a unique mixture of Portuguese, Arabian, Dutch and British styles; it is full of historical testimonials, both Indian and European at once, and it serves as not just a backdrop for the Biennale, but as an imperative player of even standing.

The central location for Biennale events is the historical Aspinwall House property, built in 1879 by the Brit John H. Aspinwall as a warehouse compound for his growing trading empire. Aspinwall House lies right on the Arabian Sea, and through the warehouse's large windows one can still see ships, barges and fishing boats float by. Nearby, the famous Chinese fishing nets reach towards the sky, which due to their photogenic qualities are a mainstay of postcards of Karela. Having long been abandoned, the warehouses were opened to the public thanks to the Biennale. Renovations have been minimal; basically, only enough to ensure that the ceiling doesn't fall in and that there is all of the communications support necessary for the exhibition of artworks. In any case, don't expect a “white cube”, nor the nostalgia of Western industrial spaces. Aspinwall House is an India which has seemingly disappeared, but is actually still here: high ceilings with open wooden beaming, teak floors with prominent gaps, the steps of staircases worn down by centuries of bare feet, and intricately carved wooden doors. Breezes blow in through every chink and cranny, deftly mixing the dust of today with that of years past.

American poet Aram Saroyan's poem “lighght” (1968)

The main exhibit begins with a fundamental Charles and Ray Eames video, “Powers of Ten” (1977): a couple is shown picnicking in a Chicago park, and every ten seconds the camera pulls back ever farther – a meter, ten meters, then a hundred, a thousand, and so on, until far in the distance we see the Earth, the Solar System, and then our own limits of perception. Then, just as quickly, the camera heads back, until it goes as far inwards as a proton in the hand of one of the picnickers. Its poetic message is that the world within us is just as infinite and unexplored as the emptiness of the Universe. Nearby, on a cracked wall, is the illuminated work of the American Poet Aram Saroyan – the world's smallest poem, as listed by the Guinness Book of World Records. Further along in the dimness glows “Undercurrent” (2004), by Mona Hatoum – a circle of electric bulbs that warns one to come no closer, but much like the Sirens, it tempts you to do just that. The black space in the center of the installation pulls like a magnet, and after a moment's surprise, you realize that the rhythm of the blinking bulbs matches that of your breathing.

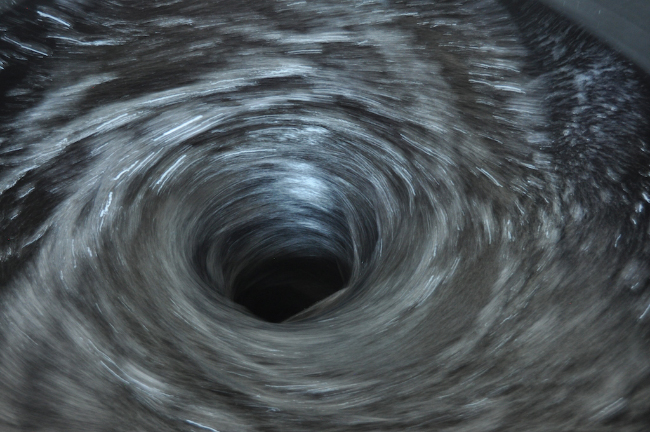

Anish Kapoor's “Descension” (2014)

Meanwhile, Anish Kapoor breaks down all preconceived notions of perception, beginning with the belief that the foundation upon which we stand is stable. His installation “Descension” (2014) has been set up in one of the of the remotest of the Aspinwall warehouses, right on the water's edge. It consists of a deep, cylindrical well in which a huge, back whirlpool of water churns with amazing strength; a “black hole” in its center hypnotically sucks in your gaze and makes it hard to look away. It is extremely loud, but the sound is completely natural – it is the sound of the power of water. Taking into account the nearness of the sea, that same power is likely somewhere underneath you as well. I must say that this is the most authentic spot in which I have seen Kapoor's work, which, taking into account the artist's superstar status, is increasingly being shown in much more prominent exhibition spaces. In these places, his works – although impeccably lighted with not a speck of dust on their sparkling surfaces, and without any instructions on how far away to stand from it so that, God forbid, you don't succumb to a cerebral imbalance – seem to have slightly lost their “flesh and blood”.

Vietnamese artist Dinh Q Le's “Erasure" (2011)

And then there's the Vietnamese artist Dinh Q Le, who at ten years of age fled the Vietnamese and Cambodian conflict and escaped with his family by boat, to Thailand and later to America. In his piece “Erasure” (2011), he illustrates the fate of thousands of other similar refugees through his own history – the floor, upon which stands a wave-beaten, broken boat, are strewn thousands of photographs depicting families who have had to (and still do) flee their countries because of military conflict.

Several of the works on display at the Biennale are attended by student volunteers who, it could be said, attempt to explain the art to visitors. It is an admittedly blessed task since for a large number of visitors, this is their first exposure to contemporary art, and the goal of the Biennale is, undoubtedly, that this not be their last.

Another phenomenon particular to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is the marked vibrancy of its visitors. Although a part of the crowd is made up of art professionals and art followers (both local and foreign), the majority of the visitors are the simply curious – people who have no direct link to art and creative forms of expression: large, multi-generational Indian families, teachers and their students, rickshaw drivers, taxi drivers, Kochi locals and Indian tourists. Colorful saris and European attire mingle in a speckled mix of people crowding about artworks and reading the accompanying descriptions with great interest. The Biennale's motto is “This Is My Biennale”, and strolling through it, one gets the feeling of being at a national celebration, and without any hint of the snobbery or elitism (and the attendant haberdashery) that is usually associated with the contemporary art scene. Something like that would be truly absurd here, for what kind of elitism is possible in the daily chaos that is Kochi? It is an unending honking of tuk-tuks, wandering cows, chickens and flea-ridden dogs, a waterfront fish market, shouting sugarcane juice peddlers, and swathes of decorations celebrating the Christian New Year and Hindu holidays. In addition, the entrance fee for the Biennale is very affordable – 100 rupees, or about 1.50 euros. Whoever you may meet during your time here, be it a rickshaw driver or the owner of a fancy hotel, even one whole month after the opening of the Biennale, every conversation eventually leads to the Biennale. Ever since the Biennale's official recognition on the map of world art events, it has naturally become a tourist magnet; established hotel owners are contemplating expansion, and a slew of new lodging establishments have opened since the first Biennale.

David Hall

There are eight venues for the Biennale in total. One of these is David Hall, found more in the center of Kochi. A colonial-style bungalow built in 1695, it used to belong to the Dutch East India Company and was used to house military personnel. The Biennale notwithstanding, David Hall is also famous for its courtyard café which serves the best pizza in town; baked right in front of you, it really is very good. Evenings here tend to attract various bizarre indophiles – from French actors to Columbian social-equality activists – who like to give readings and performances. They “collect” their audience of victims right from the street. One of the artworks on display at David Hall, “Pan-anthem” (2014), by the Mexican-Canadian artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, has a very fitting interplay with the history of the building. It is an interactive sound installation that schematically illustrates the per-capita military expenditures of various world countries, in increasing order. All along one wall are speakers that play military marches – the speakers turn on once you near them, and the larger the expenditures, the louder the music plays; culminating with, of course, the USA, Russia and Israel. Lithuania, meanwhile, is on the same level as the Seychelles and Italy.

Pepper House

Another colorful Biennale venue is Pepper House, also a onetime warehouse compound with Dutch ceramic-tiled roofs. One side of the building is adjacent to the sea, while the other faces the street; in the middle is a large courtyard. It was once rumored that Pepper House was to become a luxury hotel, but luckily that hasn't happened, and the building is currently under the wing of the Biennale's foundation; it is also used for art events other than the Biennale. Pepper House contains a full-time café, a library/reading-room, and occasionally space is opened up for artist residency programs. The most stirring of the objects on view at Pepper House is the seaside sculpture “Chronicles of the Shores Foretold” (2014), by Indian artist Gigi Scaria. It is a huge metal bell hoisted up by bamboo poles, and it functions as a fountain. The inspiration behind the piece was ancient local legends about Christian missionaries who came to Karela in just as large droves as the spice traders. Oftentimes the missionary ships carried along large bells, slated to hang in the churches that they hoped to build in the newly-acquired colonies. Apparently, not all of the ships managed to reach the shores of Karela, and the weight of the bells helped bring the ships down. According to legend, once a year a bell rises out of the seawaters and rings, thereby awakening in the local people the memory of this historic and cultural part of their past.

Indian artist Gigi Scaria's “Chronicle of the Shores Foretold” (2014)

In a sense, this work perfectly reflects the circulatory system of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale – it does not provoke for its own sake, but rather, through the language of art, it speaks about things and issues that are known and understood by all. It encourages one to observe and think, and insofar as it is possible, to also become involved.

In any case, if you happen to be in India up until March 29, then the Biennale is definitely worth a visit. If not, be sure to schedule a visit two years from now. All signs indicate that the scope of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale will only increase in breadth and strength.

Chinese artist Xu Bing's “Background Story: Endless Xishan Mountain Serenity” (2014)

Indian artist Navjot Altaf's “Mary Wants to Read a Book" (2014)

British artist Hew Locke's “Sea Power” (2014)

Italian artist Francesco Clemente's “Pepper Tent” (2014)

Through March 29

www.kochimuzirisbiennale.org