The Cabinets of Pessimism

09/03/2015

You cannot enter the exhibition “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector” in London’s cultural center the Barbican with a backpack or even a purse. Those are confiscated in the cloakroom by the lovely young women and men (of course the Barbican only employs young charismatic people, you won’t see any old museum pensioners here) who are slightly embarrassed having to justify this rule, as if saying that they have nothing to do with it; please take the important stuff with you (an iPad, a phone, a case for glasses, a wallet, a water bottle) in this transparent plastic bag, put everything in there safely and walk around our beautiful exhibition. I got confused by the mixture of their politeness, their manners and their arrogance, so I hesitated, and as a result forgot to bring the main tool, my glasses for nearsightedness. I had to go back to the cloakroom, and not without fear: it is a well-known fact that cloakroom workers love to give out things to scatterbrain visitors for the second time in order to snoop around their pockets and triumphantly pull out the wallet or the tissues. This time was different, they exhibited knowing smiles, there was an instantaneous exchange of the jacket and the backpack over the counter, and as I transferred the glasses case into the transparent bag, I headed to the ticket checker. Here is my press accreditation. Thank you. Where is the beginning of the exhibition?

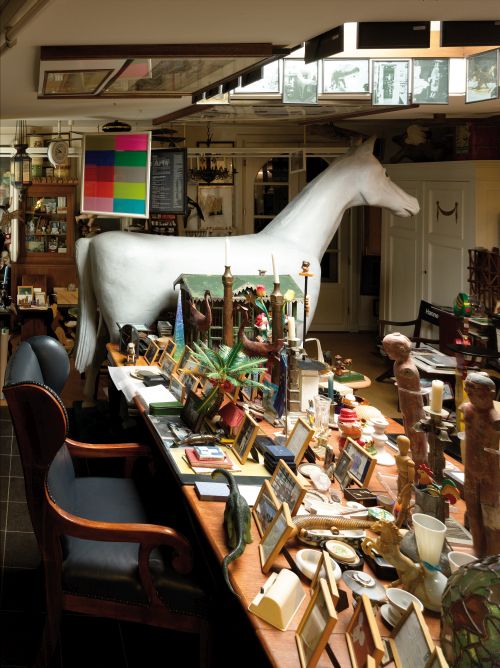

HANNE DARBOVEN. The 'Picasso' room of Hanne Darboven's studio. Photo: Rainer Bollinger

As I walked through the halls, I still couldn’t understand why they needed to take our bags and purses. Were they really afraid that the visitors would steal one of the examples from the collection of knick-knacks (and serious artifacts) that were collected, or still being collected, by the British and American artists? Who would get it in their head to steal a trashy naive provincial American artwork collected by Jim Shaw?

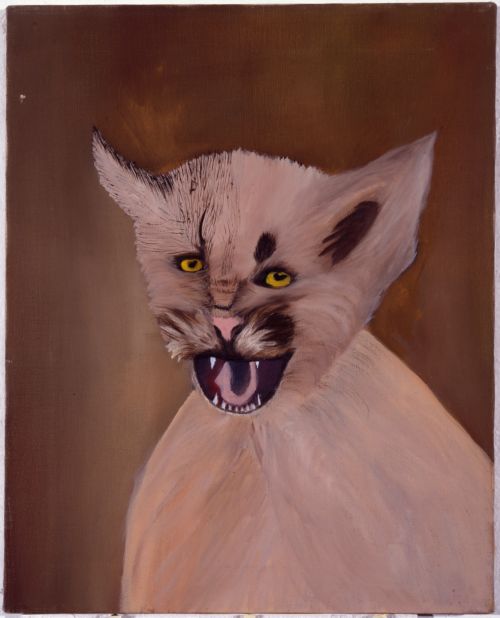

JIM SHAW. Pink Mountain Lion on Brown Background

And who would want to steal the cover of The Rolling Stones “Tattoo You” vinyl (which, by the way, I used to have about thirty years ago, and then somehow lost due to the vinyl being completely useless to me), that hangs among hundreds of other LP covers in the hall with Dr Lakra’s collection? And even the acrylic rags, even if they do have the designs of Vera Neumann, that were collected by Pae White? Undoubtedly, the exhibition had items that would be suitable for an art thief, such as netsuke, Indian artworks of the 16th century, Japanese prints of the 19th century, handwritten musical notes written by Philip Glass, and so on; let’s not even mention the collection of skulls, both real and fake, assembled by Damien Hirst. But everything valuable is locked away in cabinets, standing or laying underneath the impenetrable glass. Therefore a potential intruder is left with merely the pitiful soft toys and the rubbish porcelain from Martin Wong’s collection, which is indistinguishable from what you can buy for a penny from a Chinese shop or from a pound store. What creates the value of the collected trash exhibited here? The word Barbican? Names like "Sol LeWitt?" The fact that these collected set of items belong to these artists? The cost of the works of these artists plus the presence or absence of their names in books on contemporary art (by the way, it is amusing to reflect on the strange combination of the words “contemporary art” and "textbook")? Whatever the answer might be to these questions, one thing is clear: we are faced with a socio-cultural system of frames that are superimposed on one another. Once inside the system, every one of those vacant and pointless things gains importance, value and (most importantly) a price. We were taught this by Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists, the great Beuys proclaimed the same in front of the whole Fluxus choir, the pop artists, conceptualists, and some of the former Young British Artists hold this claim as well. Tens of thousands of "contemporary artists" around the world believe in this as they painstakingly collect and classify trash. Omnipotent political economy of contemporary art rests on recycling. "The economy must be economical," was taught to us by the wise late Soviet leader Brezhnev.

It wasn’t an accident that I used the word “trash”. I think about 90% of the exhibited items in “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector” is just that, but in a wider sense of the word. It’s the trash of time, the trash of history. There was a plethora of toys, rags, teapots, salt shakers, jars, boxes of “Western” stuff (even though some of them look more “Eastern”) of the mass production between the years 1900-2000; some books and pieces of home furniture; amateur photographs, old postcards, posters; previously mentioned LP covers. Every two weeks I lazily browse all these things at the hipster vintage fair not too far from my house, on Stoke Newington Church Street. You can also make a whole exhibition from the things one can find at the fair.

HANNE DARBOVEN. The desk room of the Hamburg home and studio of Darboven. Photo: Felix Krebs

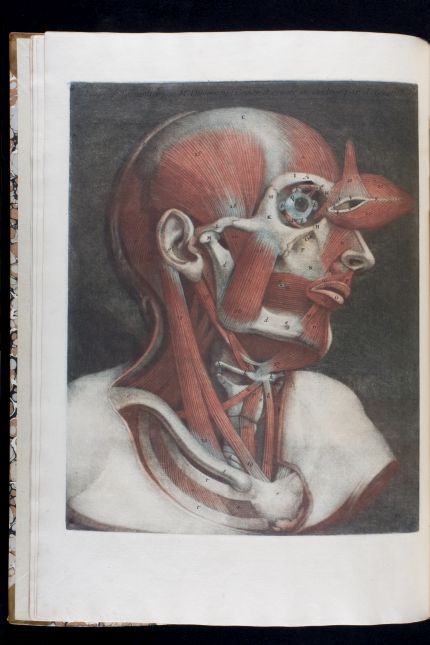

No, I am not criticizing or grumbling, not at all. The exhibition is extremely interesting and instructive, which I will explain a little later. Moreover, the remaining ten percent of the exhibits are very curious, and some of them are real masterpieces in their own way. The collection of the photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto has a great set of anatomical images and books of the 18th century, French and (what is really valuable) Japanese. It wasn’t until the middle of the Enlightenment Age that doctors in this country were forbidden to cut corpses.

HIROSHI SUGIMOTO. Jaques Gautier d'Agoty Three Types of faces, plate II copy

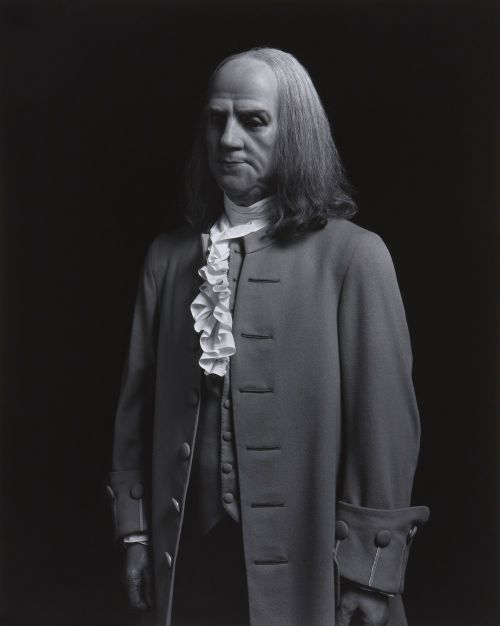

While comparing the detailed anatomical drawing of Jacques Gautier D'Agoty (1746) and those of an anonymous Japanese doctor, where the body was shown as an illustration to some mystic treatise, a lot can be understood, not only about the gap between Western Europe and the Far East (which is obvious and banal), but also about the work of Sugimoto. This is why the exhibition was arranged, to show the artists as collectors, to show the art of the artists with the background of their collections. Sometimes this worked, sometimes it didn’t. The former happened when the artist was doing something completely different to the objects of his collection, used other media, or something of that sort. Sugimoto fit into this category; this Japanese artist, in particular, is famous for a series of photographs which show wax figures of famous historical persons. Death squared - inanimate figures captured by media that eradicates.

HIROSHI SUGIMOTO. Benjamin Franklin, 1999

It is the same in Damien Hirst’s collection. This great man (really great; please take note that I did not use the word "artist"; let’s call Hirst an "art-activist", bearing in mind the mixture of traits only present in him: a mixture of arrogance, cynicism, the finest sense of aesthetics and a steel grasp on finance) has been assembling collections for a lifetime. He did this in his childhood and adolescence, when he had no money but collected all sorts of rubbish; when the money was there, the collection grew and became a work of art, and a symbol of our time, no less than Hirst’s actual art. The artist’s obsession with death is well-known; one of his favorite articles to collect are skulls. There are real skulls that Hirst buys around the world (in the Western part of the world it has become too difficult to acquire skulls, now he must turn his wishes to the East, like Putin's Russia), and artificial ones, some of which have been amazingly crafted. The Hirst section of the “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector” exhibition has an amazing cabinet which showcases two rows of skulls. The bottom shelf has an English marble skull with an iron hook made in the 17th century, a bronze skull of unknown origin from 16th-17th centuries, a stone skull with a polychrome surface created by an anonymous artist around 1680, and another marble skull from the 17th century, although the place of origin has not been set. The top shelf has two boxwood skulls from the 17th century (one of them German), a small model of a Neanderthal skull made of ivory from the 19th century, whose country of origin is unknown, and - pay attention! - two real human skulls. One of them is from the 19th century and has a lead bullet stuck in it, the other is from 18th-19th century and called "big". Indeed, this skull seems bigger than my own head, and mine is very average.

Any of the exhibition visitors would gladly snatch these items, together with John Cage’s musical notes collected by Sol LeWitt or especially the amazing African masks and samurai warrior helmets collected by Arman. Not because the visitors are greedy, but because those items are truly spectacular. Going back to Damien Hirst though, his collection also has a set of taxidermy animals and birds (there is one especially beautiful branch with two dozen colorful birds sitting on it).

DAMIEN HIRST. Birds display. Murderme collection

Looking at this set, it is easy to understand where the palette of Hirst’s latest masterpiece “Last Kingdom” was born.

DAMIEN HIRST. Last Kingdom, 2012

So in this particular case the curators Lydia Yee and Sophie Perrson did everything correctly. In some other cases the plan failed, as often the art object of the collector hardly stands out from the objects collected in his collection. In this case it can be argued that the collection of the artist became the most important of his works, which is exactly what happened to the late Martin Wong, his mother Florence Wong Fie and younger artist Danh Vo. This is what happened to Wong: after his death from AIDS, his mother gathered everything that her son collected; later Vo joined in the process of collecting and classifying the collection. The result was a continuing transformation of the artifact, which was constructed by three generations: mother, son, son’s follower. This was a kind of generous parody of medieval cathedrals, as this product, often unfinished, took five hundred years of construction in the most diverse periods using very different techniques. Only the Cathedral is a place where people pray to God, the pride of the entire city, if not even the whole country. The Cathedral was sublime, due to the height of the cathedral towers and crosses.

DANH VO. I M U U R 2 (artifacts and tchotkes that belonged to Martin Wong). 2013

The kitsch collection of the Wongs and Vo is a colorful and slightly pathetic memorial of pop culture of those times, when pop culture still consisted of things, not a combination of dual codes on the computer screens. But isn’t being “pathetic” one of the basic categories of contemporary art? Contemporary art in some ways claims to be hyperrealistic, to be a part of life, almost indistinguishable from it. If life is pathetic, then art is rightfully pathetic also.

Overall I would say that a step-by-step description of “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector” is almost impossible, as it encompasses fourteen collections of fourteen curious artists, and each of the collections demands a proper description and discussion, as well as those artists themselves. The only way I can escape endlessly dragging out my already long text is to formalize and conceptualize what was exhibited at the Barbican. Here, as always the case, history will lend a helping hand. After all, it doesn’t teach anything as much as it helps to get out of difficult situations. The main thing is not to make historical analogies. Before it was one way, now everything is completely different.

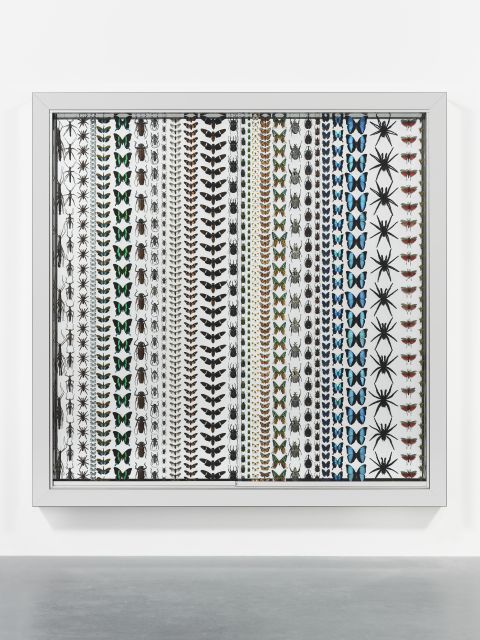

First let’s start with formalization. The exhibition showed fourteen artists-collectors: Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst, Arman, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Martin Parr, Sol LeWitt, Martin Wong (plus the uncounted mother and Danh Vo), Peter Blake, Howard Hodgkin, Jim Shaw, Pae White, Edmund de Waal, Dr Lakra and Hanne Darboven. Each collection of each artist included an artwork or two by the same artist. The assembled collection I would divide into three categories with the principle of collection and placement. The first one is the “cabinet of curiosities”. The second one is the “collection of other art” or even “museum”. And the third one is “memorabilia”, sometimes bordering on “paraphernalia”. Each of these types was not a coincidental choice of the artist. It speaks not only about the artistic method of the collector, but also about the special method of relations with the past art, and history in general. Let us focus now on the first category, as that is the most interesting.

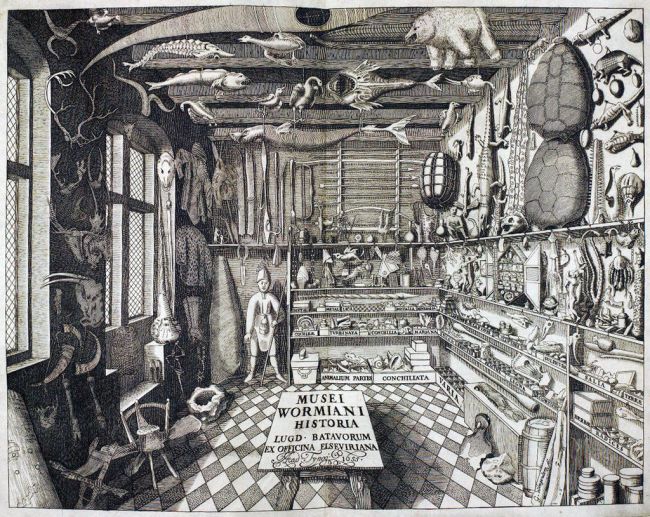

“Cabinet of curiosities” usually gets translated into Russian as “cabinet of rarities”. There is a certain complexity and inaccuracy here. First of all, in modern English the word “cabinet” means “wardrobe” or “closet”, but some time ago this word meant “a small room” which had a particular purpose for the owner, a place where one could disappear to do some important business. Secondly, the word “curiosities” does not equal “rarities”, but also “ancient things” and “curious items”. Each of these definitions are a bit off in Russian. The genre of these “cabinets” appeared in the Renaissance period, when aristocrats, monarchs, and even just scholars with money would collect the most diverse items into these cabinets, items that would strike them as unusual visually or by their origin. Here you could find dried exotic plants, never before seen animal taxidermy, the rubbish of other historically or geographically different cultures and civilizations, rare minerals, paleontological exhibits and so on. Even just from these examples you can see that the word “rarity” is not really appropriate here, as many objects were not rare at all (like stones, for example, or the archeological rubbish that was literally under everyone’s feet before archeological times began). This was also the reason why it is hard to call all of it “ancient”, because the taxidermic alligators and the dried exotic plants were contemporaries of the collectors, so they weren’t exactly ancient. In my opinion the more correct term is “curiosities”, even “exoticisms”, although even here we are faced with the problem that some of the exhibited items even then looked so banal that their status as something unusual or unseen (here is another good description: “cabinet of the unseen”) was given to them just by their place in those cabinets. In other words, all this trash became interesting only after being placed in specially made frames, a similar situation for contemporary art.

“Musei Wormiani Historia”, front page of the famous issue of “Museum Wormianum”, which has Ole Worm’s “cabinet of curiosities” shown (beginning of 17th century)

The “cabinets of curiosities” were collected for almost three centuries, before the emergence of modern sciences and the intertwining of humanities. Nature did not differ from Culture, animals and plants lay side by side with human crafts, books, coins and paintings. Similarly, Art and Life were mixed there as well, magnificent vases and two-headed monsters. The methods of mixing as well as the principles of distribution and inventory of the objects in the “cabinets of curiosities” in the Baroque era and in the Age of Reason were different, Foucault wrote about it in "The Order of Things". Here we are interested in something else: why were any of these items needed at all? Here are several answers. First of all, "cabinets of curiosities" served as a symbol of power over things from current and ancient worlds, and therefore power in general. A "cabinet of curiosities" was a miniature world, often supplementing the ordinary world, the world of non-curiosities. No wonder then that among the most famous "cabinets" were the collections of the famous Austrian Emperor Rudolf II and other monarchs as well. Secondly, they are, of course, collections made with the implicit cognitive purpose, a kind of material for future research, which often did not take place after all. Some of these collections built famous museums, for example the collection of doctor Hans Sloane created the British Museum. Finally, the "cabinets of curiosities" replaced the collections of Christian relics, which, of course, lowered the bar of spiritual flights of the gatherers, but made the process of collecting much more affordable. The Christian world had dozens of nails that nailed Jesus to the cross, a lot of bones and locks of hair that belonged to the saints, and many other relics, but despite all this galore, the number of such valuable items was still limited. But as for alligators and ancient coins - there is an (almost) infinite amount of them.

In the “cabinets of curiosities” one could also find the paintings of contemporary artists, some even famous and great, but in the framework of the cabinet they were still equal to everything else in the collection. The whimsical Arcimboldo, who was a court painter of the Emperor Rudolf, quickly understood this and started making canvases whose subject was this “curiosity” itself: portraits consisting of fruits, vegetables, fish, and other such things. This became curiosity squared. In some way Damien Hirst, who is today’s main enthusiast of the classical “cabinet of curiosities” genre (unconsciously), is trying to combine in himself the Emperor Rudolf and the court painter Arcimboldo. As an artist, he creates curiosities, and as a collector he collects them. Additionally, in contrast to, say, Jim Shaw, his works are different in quality from the items in his collections, he does not return to the episteme of the Baroque or the Enlightenment, he reconstructs them from contemporary materials as another possible way of artistic thinking. His own brilliant skull and the boxwood skull from the 17th century are completely different.

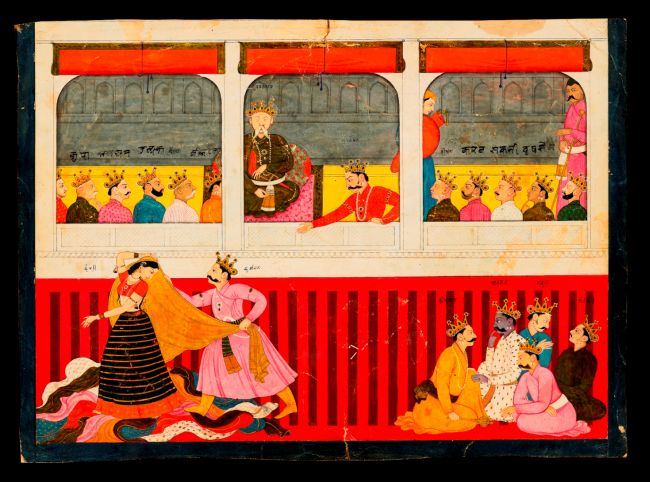

We can speculate all we want, why Hirst, or Sugimoto, or LeWitt even need their “cabinets”. The old-school explanation of “inspiration” we should push away immediately. For inspiration Howard Hodgkin collected old Indian artworks, he said it himself that he is not interested in their artistic value, only in the palette, colors, pigments that he “uses” in his own abstract canvases. Hodgkin has a “collection of other art”, a “museum” that is always nearby when he needs to feed his vision and his memory with a rare palette.

HOWARD HODGKIN. Attributed to Nainsukh, The disrobing of Draupadi, 1760–1765

Another explanation is that the collection becomes the building material for their own art, as in the case of Dr Lakra or Wong, although in the latter we are dealing again with the cabinet of curiosities of another sort. This option is also not particularly interesting, as both artists don’t create their own frames, being content with the ready-made frames of pop culture.

DR LAKRA. Album covers fromthe collection of Dr Lakra

And finally, the humanly lovely but not very inspiring strategy of “memorabilia”: Peter Blake nostalgically collects little elephants, which he counted by the radiator in his grandmother’s house, and Edmund de Waal cherishes the netsuke he got from his uncle Ignace Leon von Ephrussi.

But my own heroes of the exhibition “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector” are about something else.

This is a very pessimistic point of view about the nature of art and of people in general. There is no progress. There is no meaning either. To understand the world that consists of an uncountable amount of phenomena is impossible, because they are not tied together anyhow. The only way to create some kind of ties between things is to choose the most superficially curious objects and to place them in a cabinet or to hang them on the wall. We are in the kingdom of total artistic whimsy, whose only goal is to create at least a shadow of curiosity for the contemporary public by veiling it in a phantom nonexistent meaning. Tomorrow the public will forget all about it and the curiosities will stop being curious, the rarities will stop being rare, and the exoticism will stop being exotic. Art has no goal and is very “in the moment”, so let it entertain us a little here and now. And the world is also so incomprehensible, so let it remain this way despite all our bags of tricks. In this way of thinking a precise anatomical drawing of a French man from the 18th century is not any more progressive than the naive anatomical drawing of a Japanese man from the same time. This is not a cabinet of curiosities, those are cabinets filled to the brim with the steady, heavy and even cynical pessimism.

P.S. I understand now: we are not allowed bags and purses inside the exhibition due to the same impenetrable pessimism of human nature.

ANDY WARHOL. Cookie Jars assembly

P.P.S. Andy Warhol’s collection was a special case - his collection was one full of all kinds of pop culture stuff. As per usual with this giant of the art industry, he had everything together, the building material of his own things, consumer psychosis (Warhol bought every possible trash in boxes, brought them to his studio, and often didn’t even unpack them), and even socio-cultural gesture of the artist, who put his whole life to undermine the romantic monument of the artist, the “Great Creator”. The artist is a vulgar philistine and a serial consumer, therefore his art had the same vulgar mass-production properties. Those were the words and the life of Andy Warhol. Although you know this without me having to tell you so.