Art Depicting the Best of Worlds

(the bourgeoisie and the invention of impressionism)

07/04/2015

In 1878 a famous Parisian journalist Albert Wolff wrote in “Figaro”: “Rue le Peletier is having a bad time. After the fire at the Opera, here is a new disaster that has struck the quarter. Durand-Ruel has just opened an exhibition of what is said to be painting...” The poisonous tone of the pen-wielder was in line with the spirit of the time; seven years have passed since the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, and the Parisian press, which was somewhat strangled by the Louis-Napoleon regime, spread its wings and went back to its normal business. And its normal business was, of course, gossip, slanderings, sincere and commissioned articles against enemies, covert and overt appraisals of friends and allies. The Parisian newspapers and magazines of that time especially distinguished themselves in resolving these problems which for that time were somewhat new. It is in the first-class feather-squeaking press that one could earn a living primarily through easy writing and, what was more rare, easy thinking. Albert Wolff was more of the writing rather than thinking type: he was born in 1835 in Cologne and got a degree in Bonn, after which he moved to Paris where he was a secretary to Alexandre Dumas (père), then became one of the editors-in-chief of the satirical magazine Le Charivari, which primarily focused on political caricatures and scandals. The seasoned pencil pusher wrote novels, plays, memoirs, but all this remained in the history of Paris of the Second Empire and the first decades of the Third Republic. This period is very interesting on its own, as Paris was the “capital of the world” as Walter Benjamin wrote. It sounds a little exaggerated but it was the truth, at least the same amount of truth as Manchester was the industrial capital of the world in the second half of the 19th century. Everything new, or at least almost everything, in the art and entertainment circles was produced and consumed in Paris, as everything new (or almost everything) in industry was produced in Manchester. Today Manchester is as dead to discussions about industrial centers as Paris to views about new art.

The capital of everything new and exquisite was dominated by quite conservative tastes, especially in the attitude toward art. Academic art was still very much in favor as the true official style of the Second Empire. With that there was also the picturesque Orientalism, a sight for sore eyes that sometimes got tired of seeing the cold military and the usual visual pornography of Louis-Napoleon’s time. Odalisques. Harems. Eastern bazaars. Naked boys playing their reeds in front of the sensual fat old Pashas. Snake charmers. Among those two polar opposites remained the art that makes us praise France of the 1840s-1870s, the Barbizon School, Courbet, Corot. Ingres and Delacroix stood on the sides, arguing. In risky situations the first hid behind the Academic artists, the second hurried to get lost among his own successors - Orientalists. All in all, a great time: Baudelaire visited Parisian salons and wrote genius articles, in one of which, by the way, he used the word “modernité” (modernity), which is now a household term. The Paris Salon didn’t take paintings from many artists, which is why there was a huge scandal in 1863. The annual exhibition was visited by none other than the emperor himself with his adjutant-general LeBoeuf. During this visit the monarch expressed confusion as to why the rejected (by the art council) paintings looked very similar to the accepted ones. Having heard the barely audible explanations of the jury, the charitable Louis-Napoleon ordered to provide the offended artists a "place". This creation of the highest order, the Salon des Refuses, was preceded by the following statement from the Emperor: "The emperor has received numerous complaints about the works of art that the jury of the Paris Salon rejected. His Majesty, wishing to give the public the opportunity to come to their own conclusion about the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the rejected works will be on display in another part of the Palace of Industry. This exhibition will be voluntary, and those who do not wish to take part in it will only need to notify the administration, which will immediately return their works.”

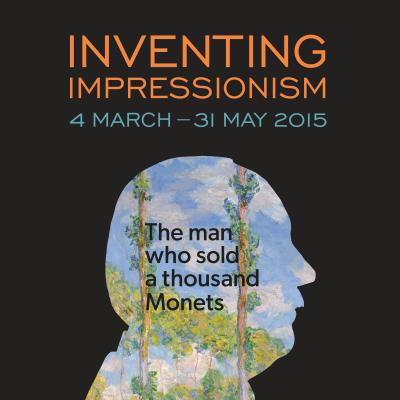

Louis-Napoleon is one of the inventors of Bonapartism, which is a well-known authoritarian regime based on a complex combination of social forces, that in all other cases are actually competitors. The formation of the Second Empire had a colorful concoction of interests in its foundation: the military and the bureaucracy, the peasantry of all varieties, small and medium bourgeoisie, the financial magnates who were disappointed both in the relatively liberal reign of Louis Philippe, and in the unstable Second Republic which arose after his overthrow. The special feature of Bonapartism was the fierce and clever rhetoric, especially nationalism. At the same time Louis-Napoleon kept playing with the artistic sphere: Dumas (père), Theophile Gautier and many others could be seen at the salon of the Princess Mathilde (Gautier became her librarian in 1868), Prosper Merimee was friends with the Emperor who also brought the writer into the Senate. As for artists, the same Theophile Gautier was the head of the National Society of Fine Arts, where Delacroix, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Gustave Dore sat in the management committee. Naturally, the Second Empire had irreconcilable internal enemies, like the republicans and the socialists, not to mention the monarchists (Legitimists and Orleanists). Louis Auguste Blanqui spent the first few years of Louis-Napoleon’s reign in prison, then was pardoned so he went into exile but in absentia was convicted again. The artist Gustav Courbet, the one who was rejected from the Paris Salon, hated Dumas (père), preached socialism (Proudhon admired Courbet), and when the Paris Commune started Courbet took such an active participation in it that after peace was settled he was thrown in prison for half a year. The “Still-life With Apples” (1872) that Courbet painted in the Sainte-Pelagie Prison is one of the 86 works from different artists at the Inventing Impressionism. Paul Durand-Ruel and The Modern Art Market exhibition that opened in the London National Gallery.

Gustav Courbet. Still-life With Apples. 1972

The main character of the exhibition was the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel who opened an exhibition in 1878 on Rue le Peletier and exhibited the “Still-life With Apples” in 1872. Durand-Ruel didn’t share the political views of Courbet, as he was an energetic busy working risky businessman and a real bourgeois (in a good way, not in the Marx or Flaubert understanding of the word). It is interesting to note that the political front of the Second Empire did not coincide with the aesthetics. Both sides of the political front were favored by Orientalists, Romantics, and even the lovers of Academism. But Albert Wolff was not really interested in civil ardor. When his fellow countrymen invaded the beautiful France, he opted to sit in Brussels, and after the war returned to Paris and got French citizenship. Wolff was one of the most famous representatives of feuilleton of his time. The feeble (he did after all die of tuberculosis) Russian poet Semyon Nadson called Wolff’s book “Mémoires du Boulevard” “a row of shallow commentaries about the different ill-reputed dens and biographies of social renegades and courtesans that nobody needs”. Truth be told, the same could be said about Proust’s saga. Poor Nadson wrote a review that was an excellent example of the heavy provincial jealousy of the Russian intelligentsia toward everything light, witty, everything that was escaping the unbearable Slavic hysteria. Wolff was one of the classic examples of a typical bourgeoisie newspaperman, therefore his aesthetic views were also bourgeois, although bourgeois in the spirit of 1840s-1870s. He hated new art and most of all he hated the Impressionists, clearly favoring the Academic School, such as Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier who illustrated the Bible and ”Orlando Furioso”, who painted the great deeds of Napoleon the Great (Napoleon I in 1814”, “1814. Campagne de France”) and Napoleon the Younger (“Napoleon III at the Battle of Solferino”).

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier. Napoleon III at the Battle of Solferino. 1861

The last of those works was sold for an unimaginable (for those times) amount of money: 200 000 francs, only to be bought after a while for four times that price. Let us compare: Durand-Ruel paid Millet in 1872 for the painting “The Sheepfold, Moonlight” 20 000 francs, which was considered at the time incredibly wasteful. At the exhibition in the National Gallery this painting hangs under the number 22, and it is in the second room which is called “The Beginning”. Courbet’s “Apples” are also there, under the number 18.

Only Wolff’s war against the Impressionists can justify his poisonous remark about the exhibition that was organized by Paul Durand-Ruel at Rue le Peletier. This place was famous, since it was on the Right bank of the river, next to the recently hacked boulevards of Haussmann’s renovation of Paris, and the Place Vendôme and its column (Gustave Courbet led overthrow of the column during the Commune period). This was a street famous for its art shops and galleries. The house number 8 hosted the gallery of Alexandre Bernheim, a friend of Courbet, who sold Theodore Rousseau and Corot. At the end of the 1870s the district of Rue le Peletier and the neighboring Rue la Fayette became the most important place for contemporary art in Paris (and therefore in the whole world). Baudelaire asked the photographer Nadar to visit one of the galleries there and bring an homage to Goya’s “Duchess of Alba”. Degas came there from his home in Place Pigalle to take a look at the Corot at Bernheim’s and even to purchase Delacroix. 12 years later Gauguin came there and studied old and new painting by examining the galleries’ windows. Rue le Peletier and Rue la Fayette became the center of the bourgeois world’s new industry, which was the art industry. Durand-Ruel became one of its founders and main characters. His main achievement was that he managed to make the bourgeoisie stop loving the Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier and start liking Claude Monet. And he didn’t just make them like Monet, he made the bourgeoisie love him forever by recognizing Monet and all of Impressionism as their own, singularly and truly their own. And by recognizing and loving Durand-Ruel made them purchase the art, and as much of it as possible. The times of Albert Wolff were ending.

Here the reader can ask a completely logical question: why did I just read all that previous information, when the article is supposed to be talking about the exhibition at the National Gallery in London? Who needs this plethora of facts and half-forgotten names? Wouldn’t it be better to describe what was exhibited in the famous museum on Trafalgar Square, to demonstrate the author’s opinion on the great art of Manet, Monet, Pissarro and Renoir? That is the problem, it wouldn’t. First of all, it is foolish to discuss the production of the art flow that was already recognized by all as “great” and somewhat “exemplary”. What can be added to the thousands of monographs about the Impressionists and to hundreds of their biographies? Nothing. As for my own feelings toward the consumed artistry and aesthetic feelings, I think restaurant art critics should take care of it.

Secondly, Inventing Impressionism. Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market is not about the Impressionists at all, its theme is the early days of the art industry and its main character is one of its founders. In this sense the exhibition was a failure.

It is pointless to talk about Paul Durand-Ruel’s days and his work without the knowledge of the historical and cultural context, or to be more specific, it is pointless not to be reminded of it. Here we need exactly that, because even those of us who have never come across the name Albert Wolff (and that would be majority of us in the European world), those who know Baudelaire (and know about him), Dumas the father and Dumas the son, and if they haven’t read “Carmen” then at least have heard about it (or even heard the opera), are acquainted with the Paris Commune and can explain the meaning of the phrase “Madame Bovary, c'est moi”, and have enjoyed a couple dozens Impressionist paintings. This is how the latter is dealt with: Manet and Monet, Pissarro and Sisley, Degas and Renoir were real hard workers and produced art objects like factories. Due to this factor every last European and North American museum has one of their landscapes or portraits. All of the bits mentioned above can give anybody a significant amount of cultural and historical facts. All that is left is to put them in one picture, and that picture gives us the opportunity to understand what exactly is the mightiness of Paul Durand-Ruel. His character somewhat comprises the history of that time. Regardless of the obsession with the past which can be observed in the last couple of decades among the culture-concerned Europeans, nowadays history (precisely “history”, a complex contemplation of the past, not merely a story) is avoided. That is why most of the bits mentioned above are not included in the National Gallery. So what is there instead? 86 paintings, sculptures and decorative objects, all made in the period between 1830 and 1888. All of the objects are spectacular, perhaps only Renoir’s soft piglet-colored women can be quite annoying, although that depends on the viewer. There are some not so well-known masterpieces, like Degas’ “Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando” and his “Peasant Girls Bathing in the Sea at Dusk”. Every painting has a small explanation about the connection between the art object and Durand-Ruel’s endeavors. Most of the time the connection is very simple, he bought the object and then sold it. Sometimes the prices and circumstances are also mentioned. Once in a while the text states that the gallery owner especially liked the work. The first room of the exhibition focuses on his home and reconstructs the family life of Durand-Ruel, partially even his home layout. Here you can find Renoir’s portraits of the art dealer, his daughters and sons, the door of the salon that was painted by Monet is also exhibited there, Rodin’s sculpture and again a lot of Renoir, since the gallery owner was friends with him for thirty years. In the center of the room they exhibited a few chairs from that period that the viewers can sit on and imagine themselves to be the young Swann before he got involved with the sly Odette. Or even the young Baron de Charlus. Just don’t deceive yourself, this is purely bourgeoisie art; the snob Swann would snort at the sight of it and would instead go to see the Dutch Golden Age paintings or Botticelli, and Charlus would make one of his spiteful trademark remarks. This spite was of the same sort as the poison of Albert Wolff, regardless of the ethnical and social abyss between the highborn lazy dandy and the working German Jew who conquered Paris’ newspaper world.

Only having reached this point in our discussion, (and Proust’s point was very important here, because nobody was a better judge of the French society of the pre-1914 Third Republic than Proust) we can finally start to discuss Paul Durand-Ruel’s achievements. But first let us look at the chronological outline of his biography. He was born in 1831 in Paris in the family of the owner of a stationery and art supplies shop, which also sold paintings. When he was 20 years old, he left the military service to help his father with business. He travelled, studied art and the structure of the art market (although it didn’t really exist at the time). He got married and had five children, then his wife died when he was 40 years old. In 1869 Durand-Ruel inherited his father’s business after his father died. He sold Delacroix, the Barbizon School works, Courbet and Corot. The main events of his career coincided with serious political turmoil. After the beginning of the Franco-Prussian war Durand-Ruel left to go to London, where his historical meeting with Monet and Pissarro (who were also waiting in Britain for the end of the war) happened, with Charles-François Daubigny’s mediation. This is when the real history of the gallery owner Paul Durand-Ruel begins. In 1872 he acquired the first Impressionist paintings of his career: Manet’s 23 paintings in bulk, plus works from Degas, Renoir, Sisley, Berthe Morisot apiece.

After that the gallery owner bought and sold hundreds or even thousands of Impressionist works. Durand-Ruel started the popularity of Impressionism with the help of a couple of colleagues-competitors and half a dozen of writers, critics and journalists. He made the bourgeois public view the phenomenon that Albert Wolff described as “what is said to be painting” as real art, especially the kind of art that was close to their social standing. Durand-Ruel was extremely inventive and tireless: he made it fashionable to organize personal exhibitions, he requested reviews and forewords to catalogues, he kind of was the first to combine the roles of the art-dealer, the gallery owner and the curator. He also actively exported Impressionism to nearby and far away countries. The latter saved him from yet another financial crisis and the threat of bankruptcy. Actually, there were a few money catastrophes, but the biggest happened in the mid-80s. To counter that, Durand-Ruel took 289 works and headed to New York. That was how America was discovered as the richest market in the world for bourgeoisie art, and I think to this day it still remains so. Durand-Ruel’s gallery in New York existed until 1950. And finally, in 1905 he organized a huge exhibition of Impressionism, one that was unheard of at the time. More than 300 works were exhibited at the Grafton Galleries in London. Only after slaying the socially and culturally conservative American and British middle class, and even their rich class (let’s add the Russians and the Germans also), our hero was finally able to convince the French bourgeois and the French bureaucrat that Impressionism was not only reasonable as an art style, but the only possible contemporary art form. Madame Verdurin would have loved Impressionism by this point. Paul Durand-Ruel died in 1922, when he was 89 years old.

And now let’s tackle the main issue: why the bourgeoisie? Why Impressionism? What was the heroic achievement? Here is the why and the what. Until a certain point in history, the urban European bourgeoisie didn’t have their own “taste” or their own class-conditioned ideas about beauty. To be more precise, they did have it, of course, but it was never legitimized beyond their social circle. The bourgeois loved this and that, didn’t care for some others, but this was his own personal deal, he never made claims to distribute his tastes somewhere else. Of course there were exceptions, like the Flanders in 15-17th centuries, but that was a specific situation, as those places didn’t have the local nobility and its role was fulfilled by wealthy merchants. The top of the civilian Flemish art became Vermeer and the Dutch Golden Age. But as for most of the European countries, especially in France, this began at the end of the 18th century. During the French Revolution and the First Empire, Classicism and its marble civic virtues were presented as bourgeoisie art, then it was the fierce Romantic Art and the colorful Orientalism. The first attempt to squeeze between these enormous styles, to introduce a sense of reality into painting was the Barbizon School, then Corot and Courbet. But even the so-called “Realists” became too ideological for the bourgeoisie who worked hard to get where they stood and now just wanted to relax, to live quietly, to be entertained and to be distracted from unhappy thoughts of financial risks of the restless world. As for Courbet, he was dangerous anyway with his social ploys, his offensive obscenities (“The Origin of the World”) and his alcoholic mysticism. Finally, the “Realists” were unpleasant for the bourgeoisie, especially for the complacent prosperous bourgeois with aesthetic needs, because the Realists represented labor, especially heavy peasant labor, which was unpleasant, because it reminded them of the origin of sustenance. Art must be about something else, right? The bourgeois needed something different, colorful, light, picturesque, gentle, something that didn’t call into question his existence, but at the same time something he could call exclusively his own. At this point in time Paul Durand-Ruel materialized in front of the bourgeoisie and advertised Impressionism. And not only advertised, he used himself as a difficult example of what was the real value, aesthetically, ethically, politically and financially speaking.

Sketch by Manet. 1882

Inventing Impressionism. Paul Durand-Ruel and The Modern Art Market exhibits the world that Durand-Ruel offered to the bourgeoisie for a certain price. Before this world was even sketched, it already belonged to the bourgeoisie, because of the social standing, the claims and the simple practicality. It was the world of the bourgeoisie childhood homes, alleys, parks, picnics, dances, theater, cafes, brothels, boulevards. This world had obvious footprints of bourgeoisie activity, such as railroads, steamers, train stations, but those were inscribed into the overall calming attractiveness of the world. The world of the impressionists really does have a calming effect; there is no drama, there is no history, everything happens in the moment and only for the sole purpose of pleasure / enjoyment of the viewer. Moreover, everything that is painted can be the bourgeois’ property if he doesn’t already have it, everything is reachable for him: renting or buying a house in the country for the summer (in a small town), obtaining a concubine, a wife, children, pets, going to the theater, sitting in a cafe. At the very least the bourgeois could buy the painting that shows all of the mentioned features. All he had to do was to go to Rue le Peletier, visit Durand-Ruel’s gallery, choose Monet’s bright blue or soft grey-green haystack, or Pissarro’s marvelous, wet as a teary-eyed glance, boulevard, or Renoir’s plump pink female flesh, and pay a few hundred franсs, or even a few thousand, depending on the success of the last exchange transaction on the sale of cotton.

And yes, our world does not know a better world than that. You should read Proust again.