The City of Culture that is Fondazione Prada

28/05/2015

Photo:

It's been years since a museum project was so fervently anticipated as Fondazione Prada – and then lavished with compliments just barely a week after its opening. The new home of this Milanese art and cultural institution is a 1910s-era former distillery in the city's southern industrial district – Largo Isarco. Reconstruction of the building was entrusted to Rehm Kolhaas, a good friend of Miuccia Prada (the founder of the Prada fashion house), and his architecture firm OMA; OMA has also designed several Prada retail shops. Taking up a total area of 19,000 square meters, 11,000 m2 of the Fondazione has been devoted to exhibition space. Although the project is being widely touted as Milan's “new contemporary art museum”, it is not officially a museum. Nor does the word “museum” suit it, for this new art and cultural space has both formally and content-wise surpassed all normal museum standards; behind the scenes, it's already being called a “city of culture”.

Fondazione Prada is the private initiative of fashion designer Miuccia Prada and her husband Patrizio Bertelli, CEO of Prada. Set up without any government financing, it is an entirely private foundation and does not receive any tax relief. Prada and Bertelli established the Fondazione in 1995, and over the last twenty years it has organized exhibitions and initiated cultural projects all over the globe. Four years ago the Fondazione opened an art space in Venice, in a grandiose 18th-century palazzo on the banks of the Grand Canal.

Having taken seven years to erect, the just-opened Fondazione Prada in Milan has been resoundingly accepted as the flagship of the Prada art and cultural initiative. In addition, this new Fondazione marks a notable turning point in the preconceived notions of what a museum is – it challenges the classic and, up to now, limiting concepts of museum qualities which, supported by various breeds of ambition, have cropped up in the last decade like mushrooms after an autumn rain.

One could say that Kolhaas's architecture is like a neutral, office-casual suit jacket that has been placed over the shoulders of the existing brewery buildings. It does not conflict, it does not dominate, and in no way does it try to self-servingly outshine its contents, i.e., the art on display. In this way it is ideally suited to the style of Prada, which has frequently been described as “ugly chic” and “anti-fashion”. On the one hand, the “devil” of consumerist addiction wears Prada; on the other, Prada is the embodiment of intellectual snobbery. And the latter opinion still holds strong despite recent questionable developments: the brand's triangular logo is now recognized virtually worldwide (it's become just as clichéd as Chanel's double “C” and Louis Vuitton's “LV”); the market is flooded with Prada knock-offs; and of course, “The Devil Wears Prada” book- and movie-franchises and all of the related attributes thereof. Unlike many of its peers, Prada has admirably remained free of baubles, cheap exhibitionism and superficiality.

As a fashion label, Prada has conquered museums (the New York Metropolitan in 2012, with the exhibition-cum-intellectual dialog – “Schiaparelli and Prada: Impossible Conversations”) as well as Twitter, where every few moments a Prada-obsessed follower posts his or her latest sartorial trophy baring the famous label. Prada deftly satisfies both spiritual and material longings. Esteemed British fashion critic Suzy Menkes has said about Miuccia Prada: “She is a conceptual fashion person who knows in which direction the wind is blowing.”

And it must be said that Prada was well aware of this direction when organizing the Fondazione project. Even though the Fondazione's interior still exuded a strong smell of fresh paint on its opening day, this was the only visible flaw – all other “seams” have been perfectly finished, creating the feeling of a well-tailored suit. As Kolhaas has said: “The Fondazione is neither a conservation project nor new architecture,” but rather an organic symbiosis of both, and in the confines of the same space.

The complex is made up of seven historical buildings and three new ones – an exhibition hall, an auditorium and the museum. The latter is a ten-story tower which is still under construction. A glassed-in display pavilion is the Fondazione's symbolic heart, and it currently holds the grand-opening exhibition, “Serial Classic” – an homage to the relationship between the legacies left behind by the ancient Greeks and the Roman Empire. Miuccia Prada calls it a political gesture, for it is the first time that archaeological artifacts are being exhibited by a contemporary art museum. It's usually the other way round – in the search for unusual forms of expression, contemporary art exhibitions have oft made use of history museums as a platform for display. Archaeologist and art historian Salvatore Settis is the curator of this exhibition that focuses on both classic sculpture and a very popular practice in ancient Rome – the making of copies. Although classic art is closely linked to uniqueness, it is no secret that many artists, including Michelangelo, made copies of Grecian artifacts, thereby breaking down and merging the lines separating an original from its copies. The originals and their copies on view at the Fondazione Prada have been lent out by such prestigious art institutions as the Uffizzi Gallery, the Louvre, the Vatican, and the British Museum. Positioned atop wooden pedestals, the marble Greek gods and goddesses stoically gaze at their “originals” – 21st-century homo sapiens that have, by now, lost all classical ideals and contentedly swarm about outside the glass walls of the pavilion.

Right behind the new pavilion is the Fondazione's most prominent building, the Haunted House. Completely covered in gold leaf, the building's facade reflects the light in such a way that the mood of the area changes significantly depending of the time of day. The Haunted House is home to Robert Gober's installation made specially for the Fondazione, as well as to two works by Louise Bourgeois. This is the only building in the complex that requires a separate ticket for entrance; in addition, reservations must be made beforehand since only 20 people are allowed in at one time. In this case, gold really does indicate exclusivity! Don't fret if, when making your reservations, the only available times are near the end of the day – the Fondazione is not a museum, but truly a whole city for which even a whole day may not be enough time in which to experience it to the fullest degree – so trust us, the time will fly by so fast that the end of the day will arrive quicker than you think!

As befitting a city, the campus of Fondazione Prada also has cobbled streets and lawns, as well as outdoor benches and mezzanines where visitors can sit down to take a break, chat with one's companions, or just ponder what it is that you've just seen. Directly across from the exhibition pavilion is a film theater whose mirrored glass facade not only reflects the activity taking place on the “stage of life”, but optically enlarges the Fondazione's territory. The cinema was opened with the documentary film/interview “Roman Polanski: My Inspirations” – a tribute to the Polish film director. Also on the current film schedule are films by Polanski himself, shown as double features with films that have served as inspiration to Polanski; for example: “Rosemary's Baby” (1968) with “Citizen Kane” (1941), and so on.

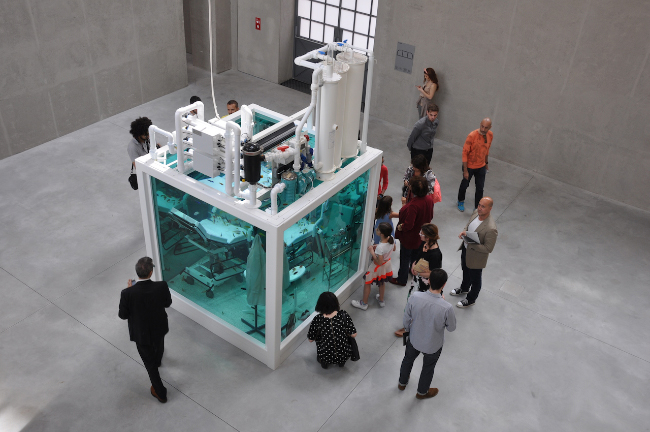

Another building called the Cistern (it used to house cisterns of whiskey and brandy) has been set aside for the “Trittico” project, which consists of three artworks from the Prada collection. The central one is Damien Hirst's “Lost Love” – a gigantic aquarium in which colorful fish, oblivious to their absurd setting, swim amongst a landscape that is basically a gynecologist's office – a table with medical instruments, an examination table with stirrups, a woman's purse on the floor, and a white doctor's coat hanging from a coat rack. The installation and all of the impressive mechanisms keeping it “alive” can be seen up close at floor level, as well as from above – when standing on a special observation platform. From this vantage point, the viewers down below – and the actions with which they express their curiosity as they look at the piece – become a sort of objet d'art themselves.

Separate rooms contain Eva Hesse's “Case II” and Pino Pascali's “A Cubic Meter of Soil”. In a room looking something like an industrial cathedral, a large flattened cube sits on the wall, illuminated by the light coming in from the large windows.

The two main galleries, galleria Sud and galleria Nord (South and North, respectively) are on parallel streets. Galleria Sud, or the Deposito, contains the exhibition “An Introduction”; its symbolic aim is to present a behind-the-scenes look at how a collector (in this case, Prada and Bertelli) initiates, creates and develops a collection. In the case of the Prada collection, this process was done rather eclectically, without a clear focus – obviously, it was more dependent on social topicalities and spur-of-the-moment feelings than anything else. As Miuccia Prada has said herself: “The artists I work with have deep insights into life, the world, and humanity. They, like I, have a passion to understand. Together, we try to make possible ideas that look to be impossible. We look for new ideas, new ways of thinking.” Visually, the galleria Sud is reminiscent of a never-ending hallway with pocket-like side rooms featuring approximately 70 works of art: 1960s classics Yves Klein and Piero Manzoni; the works of Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli (a master of parodies concerning consumerist culture) displayed on a 15th-century, engraved wooden secretary in a room with fuzzy brown walls; works by Lucio Fontana, Jeff Koons, etc. This symbolic excursion to gallery-states ends in an altogether unexpected way… in a garage: a huge industrial hangar containing automobiles that have been transformed into works of art by artists such as Carsten Höller, Rosemarie Trockel, Gianni Piacentino, Sarah Lucas, and Elmgreen & Dragset.

Gallerie Nord houses the exhibition “In Part”. Curated by Nikolas Kalinan, it was inspired by Robert Rauschenberg's 1952 photograph of Cy Twombly standing next to a sculpture of a huge hand. The exhibition is a story about fragments that are part of a whole even if they are sometimes seemingly removed from that whole. Represented artists include Man Ray, Michaelangelo Pistoletto, Yves Klein, Lucio Fontana, Robert Rauschenberg and Francis Picabia, among others.

Also part of Fondazione Prada is the Accademia dei Bambini; opening next year, this library and space for children will be the Fondazione's first project tailored towards the younger set. Right next door is Bar Luce, designed by film director Wes Anderson. The interior design copies that of a retro Milanese café, while the ceiling is a miniature take on the vaulted glass panes of the famous Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II shopping center in Milan (which, as we all know, is also home to the oldest and most legendary Prada retail store). Being an homage to Italian cinema of the 1950s and 60s, on opening day, when visitor hordes were dressed to the absolute nines (Prada is, after all, a fashion house), the bar even got its own self-proclaimed diva or two.

Unsurprisingly, the opening of Fondazione Prada has encouraged everyone to formulate their own comparison of it with Frank Gehry's Louis Vuitton Foundation – the surreal iceberg-like (or tissue-paper-like, depending on one's point of view) structure opened in Paris last year. Cultural aficionados and critics of this, the most controversial and pompous museum project of recent times, were divided into two distinct groups: those who vilified Gehry's and Arnault's architectural miracle without ever having even seen it; and those who, in spite of the structure's un-stylishness, admitted that it was a feat of technological mastery. Both groups, however, do agree that as a museum for the housing of artworks, it's nothing short of a failure. Whereas the Louis Vuitton Foundation cost about 143 million dollars to build, the financial output for the construction of Fondazione Prada has never been revealed.

And although art projects are a part of the brand's lifeblood, Miuccia has never, unlike her peers, stepped over the line in terms of merging fashion with art for pure material gain. Even if well-known artists sometimes sit in the front rows at Prada fashion shows, not a single one of them has been wrangled into creating a Prada handbag or piece of clothing with their work printed on it. In this sense, Miuccia has always maintained an intelligent distancing. The gigantic billboard with Fondazione Prada emblazoned on it at the end of the street may make it impossible to not find the museum, but Prada has cleverly positioned the sign outside of the campus' territory, thereby preserving the image of the art space being untouched by brand identity or other corporate references. In public press releases, it has been emphasized that the new Fondazione Prada will be not be a grand framework for the presentation of an illustrious private art collection, but rather, it will be a multi-functional cultural space featuring film, design, architecture and philosophy as equals next to art. As Miuccia has said herself – to her, and in the Fondazione, art is presented as a tool with which to understand the world.

In truth, although very well hidden under a mask of intellectualism, Fondazione Prada, nonetheless, does sell those handbags; but this fact is actually not such a bad thing as one would be led to believe. First of all, a handbag is a truly functional (and not only decorative) accessory; and second, without this successful handbag business, who knows when Milan would have gotten its first contemporary art museum. But hush! – it's not polite to speak of handbags making up the foundation upon which this palace of art has been built. Then again, that's the way it's always been – art is the “golden egg” that gives a brand an intellectual mark-up. Or, as in Prada's case, art just enhances what is already there.