Art As a Simulation: Nothing New

Estere Kajema

23/03/2016

We are raised with a notion – whatever you do, you cannot reinvent the wheel. Yet, the production of the wheel has evolved from wood to rubber, and from basic rubber to ultra-advanced and expensive high-class rubber. Occupying the world of hyperrealities and simulations is becoming more and more complex for creators. Using texts by Walter Benjamin, and, of course, Jean Baudrillard, as well as various examples from contemporary and postmodern art, I shall argue that contemporary visual cultures are acting as a simulation of what has been produced and created previously.

First of all, it is important to begin with an accurate description and analysis of such complex terms as “hyperreality” and “simulation and simulacra”.

The concept of “hyperreality” has been used by various postmodern philosophers and writers. For instance, Gilles Deleuze once wrote that all human beings are created as simulations – since God created mankind in his own image. The notion of hyperreality was first introduced by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard in his book Simulacra and Simulation. He defines the notion right in the beginning of the book:

“It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreality”[1]

Therefore, hyperreality is a repetition of a reality in which the actual, original reality is often lost and forgotten. In his writing, Baudrillard often compares postmodernity to hyperreality, stating that there are not many differences between the two conditions. The philosopher repeats that hyperreality is not the unreal; it presents a virtual reality which continues copying itself to infinity.

Baudrillard argues that whilst reality is responsible for production and growth, hyperreality is only able to simulate. He writes:

“Representation starts from the principle that the sign and the real are equivalent (even if this equivalence is Utopian, it is a fundamental axiom). Conversely, simulation starts from the Utopia of this principle of equivalence, from the radical negation of the sign as value, from the sign as reversion and death sentence of every reference.”[2]

Baudrillard continues with this idea by listing four possible conditions that a simulated image can occupy:

-it is the reflection of a basic reality;

-it masks and perverts a basic reality;

-it masks the absence of a basic reality;

-it bears no relation to any reality whatever: it is its own pure simulacrum.[3]

On this basis, it is fair to suggest that simulacra – which is a mandatory component of the condition of hyperreality, is a substitute for reality which has completely lost its initial attributes and conditions. Baudrillard simply defines it as “second-hand truth”[4]. Simulacra can still be truthful because they are camouflage, a replica of truth. Yet, whilst going through a metamorphosis, simulacra are subjected to losing the initial qualities of truth. By describing hyperreality as “second-hand truth”, Baudrillard is creating an analogy between simulacra and second-hand objects. Second-hand books are often slightly creased; usually, they bear writings and underlined or highlighted lines. Second-hand truth, too, is subjected to various changes, interpretations, and possible curves.

Baudrillard offers the reader a famous example using Disneyland.

“Disneyland is there to conceal the fact that it is the "real" country, all of "real" America, which is Disneyland (just as prisons are there to conceal the fact that it is the social in its entirety, in its banal omnipresence, which is carceral). Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real...”[5]

In this passage, Baudrillard states that in order to perceive something as real, one must compare it to something fake, or second-hand real. He underlines that the main quality and forte of simulacra is that they are capable of masking reality, which leads to the dominance of the simulacra over the real. This, essentially, is how hyperreality exceeds reality – by adopting the most obvious attributes of the real, it becomes a splendid and indistinguishable camouflage.

Not only does hyperreality influence production, but it also plays a major part in quotidian lives and means of communication. Real, in-flesh relationships are easily substituted by virtual correspondence. Real-life interviews are easily transferable to Skype, and romantic conversations are surely replaced by text messages and Tinder.

The invention of photography was, in some way, the beginning of a transition between modernism and hyperreality. Walter Benjamin in his arguably most important essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility”, writes:

“With the advent of the first truly revolutionary means of reproduction, photography, simultaneously with the rise of socialism, art sensed the approaching crisis which has become evident a century later. At the time, art reacted with the doctrine of l’art pour l’art, that is, with a theology of art. This gave rise to what might be called a negative theology in the form of the idea of ‘pure’ art, which not only denied any social function of art but also any categorizing by subject matter.”[6]

Benjamin writes about the foredooming crisis, unknowingly predicting the prospective crisis that the spectators have only begun to sense now, in 2016. On the same page of the essay, Benjamin states that with the invention of photography, the production of art becomes a mechanical process in which, from a single photographic negative, one can develop a variety of prints. Not only does photography counterfeit the originality of the subject, but it also gives space for the fabrication of hoaxes – which, indeed, is one of the most important and appalling consequences of hyperreality.

From the left: Tracey Emin. My favourite little bird, 2015. Courtesy Gallery Blossom, London; Tracey Emin. This is My Favourite Little Bird. Photo: seditionart.com

EDITIONS

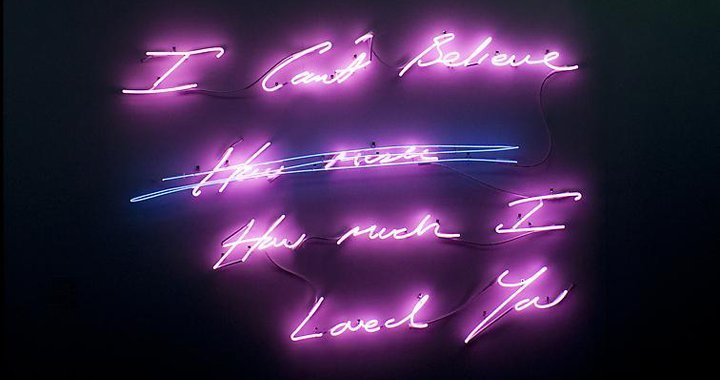

Another important aspect of the devaluation of the art market as a consequence of hyperreality is the introduction of editions. There is nothing new in the tradition of creating an artwork with various editions; however, contemporary effortless technological attributes truly reduce the significance of the original.

In 2011, Harry Blain, founder of Blain | Southern gallery, together with Robert Norton, former CEO of Saatchi Online, launched the online platform Sedition Art. This platform provides its customers the services of buying, selling, or reselling editions of digital artworks. For instance, shortly before Mother’s Day, Sedition put up for sale a copy of Tracey Emin’s digital installation This Is My Favourite Little Bird, for the price of £57, as a gift option for the upcoming internationally-celebrated day. Buyers were able to purchase a single edition – from 5,000 in total. Sedition is famous for selling digital works of art produced by such artist as Damien Hirst, Jenny Holzer, Yoko Ono, and the above-mentioned Tracey Emin – all of whom are undoubtedly giants of the contemporary art scene. The initial idea, indeed, is brilliant and very generous – most anyone with a middle-class income is given the opportunity to purchase a work of art created by one of the most famous artists in the world, and at a very affordable price. Yet, when all is said and done, by selling 5,000 editions of Tracey Emin’s This Is My Favourite Little Bird, Harry Blaine will have earned £285,000, which is the average price for two or three of Emin’s neon installations, of which there is usually just one unique edition of each.

Digitally-produced editions are nothing but a killjoy for canonical aesthetes of art – even though the most traditional artists, including Bernini, Chagall and Degas, produced various editions of their work. It is different today, though – banal mechanical reproduction of art does not require specific skills, techniques or artistic vision. It shadows and masks the original work, and, in fact, often leaves the original unknown – which, as we learned before, is the main signifier of simulacra.

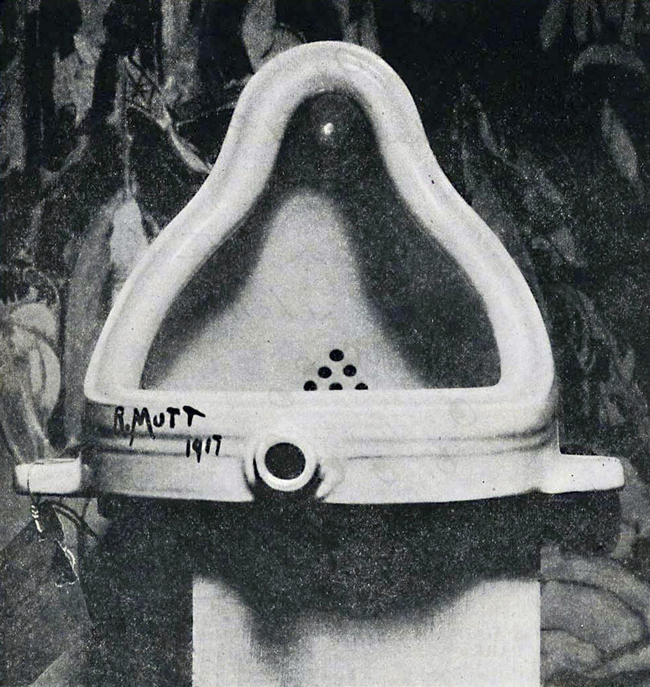

Marcel Duchamp. Fountain, 1917

OBJET TROUVÉ

Objet trouvé, or Found Objects, is an art technique which emerged in the early 20th century; it described works of art which were created out of objects which are not normally used in art – in other words, mass-produced products. The technique was used by several collage artists, including Pablo Picasso and Kurt Schwitters. In 1913, Marcel Duchamp created Bicycle Wheel, referring to it as a “readymade”. In 1917, he created Fountain, arguably his most famous work. Fountain is made out of a mass-produced urinal which the artist placed on a pedestal.

I want to argue that Found Objects, unlike editions, often broaden the meanings and possibilities of an artwork. To enhance the argument, I shall use three examples – Damien Hirst’s Let’s Eat Outdoors Today (1990-1991), Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1991) and Ai Weiwei’s Straight (2008-2012).

Damien Hirst. Let’s Eat Outdoors Today, 1990-1991. Photo: criticismism.com

Let’s Eat Outdoors Today

Let’s Eat Outdoors Today may not be Hirst’s most famous work, but it is created in his highly recognizable style. The artist puts a countryside-like barbeque set-up into a glass container that has been split into two equal parts. One half is occupied by a barbeque with raw meat on it; the second half is occupied by an outdoor table with half-finished beverage bottles and half-empty plates on it, a plate full of roast chicken, as well as bottles of condiments, salt, pepper, and used napkins. Hirst places a cow’s head underneath the table, and an electric Insect-O-Cutor [an electric fly killer] above it. The surfaces of the barbeque set-up, as well as the table, are covered with dead flies and maggots. In an interview for The Telegraph, Hirst said:

“It’s like everything you do in life is pointless if you just take a step back and look at it.”[7]

Hirst is using found objects in order to underline and emphasise human apathy and lack of motivation. By presenting an abandoned barbeque scene, Hirst is also focusing on the idea of compulsive cleaning. He argues that humans are dogmatically concentrating on avoiding dirt, but forget that dirt will always eventually find and surround them.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Untitled (Perfect Lovers), 1991. Photo: moma.org© 2016 The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

Untitled (Perfect Lovers)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres is an artist who often uses found objects in his art installations. Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1991) is an installation that consists of two clocks which are fully synchronized and always show the same time. Yet, one of the two clocks will eventually stop before the other. Gonzalez-Torres produced this work of art when he was in a relationship with Ross Laycock, who was a huge inspiration for many of Gonzalez-Torres’s works. When the artist created Untitled (Perfect Lovers), Laycock was already terminally ill. In this work, the artist is showing his fears and anxieties concerning time, as time is the most violent and uncontrollable weapon. By using an object that can be easily found in any household, Gonzalez-Torres is framing an allegory of restlessness.

In creating a parable of time that simulates and repeats the tradition of tracking time, Gonzalez-Torres is depicting his personal attitude towards lastingness. Use of a habitual object aids the artist in building a parallel between the laws of the Universe and his own subjective life and trauma, which potentially is projected towards the spectator, too.

Ai Weiwei. Straight, 2008-2012. Zuecca Project Space/Complesso delle Zitelle, Giudecca, Venice 2013. Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio/Taschen

Straight

In 2008, the Chinese province of Sichuan suffered an unbelievably strong earthquake. Following the tragedy, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei took action – he began speaking out about abuses of human rights and the rottenness of the Chinese government, as well as started an investigation leading to the uncovering of the truth about the actual number of casualties of the earthquake. These activities lead to him being arrested for 81 days, and to the confiscation of his passport up until Autumn 2015.

Straight is an installation that consists of over 150 tons of steel reinforcing bars that Ai recovered from sites that were severely damaged and destroyed by the earthquake. Ai and his assistants brought the bars back to artist’s studio, where they then spent years straightening them in order to bring them back to their initial condition. After straightening the bars, the artist arranged them into piles, thereby recreating some sort of a landscape. By giving every bar his utmost attention, Ai managed to achieve two things – firstly, he collected and preserved the physical memories of a horrible disaster in order to create a memorial, almost a bed of honor for the victims of the earthquake. Secondly, Ai performed a symbolic act of atonement.

By using the actual materials that were involved and damaged in the earthquake, Ai underlines the importance of, in the most literal sense, found objects. The artist repeats the use of bars in order to create a different lieux de memoire – a site of memory. Ai transfers materials, which once formed a house, into the gallery space, thereby reinforcing the importance of remembering.

In Latin, simulo means to imitate. In his artwork Straight, Ai imitates earthquake waves, the uneven Sichuan landscape, and housing construction – all in order to show the secrecy and inhumanity of the Chinese government.

The three examples mentioned above do not fully reject the original objects, yet they still occupy two important phases of a simulated image: each of the artworks is a reflection of a basic reality; and each of them masks and perverts a basic reality. Hirst, Gonzalez-Torres and Ai have all applied a level of their personal interpretation and connotation on top of the original purposes and functions of the objects that they chose to use.

Lastly, I want to focus on a different aspect of hyperreality – the adaptation of a stolen or borrowed image. This section is inspired by the forthcoming exhibition “Thomas Demand: L’image volée”, which will be demonstrated at Fondazione Prada in Milan. The exhibition will take a look at the history of intellectual art theft and the tradition of borrowing. I wish to highlight a work of art that will be featured at the exhibition – Sophie Calle’s The Hotel (1981), as well as another work of art that depicts a complex relationship between an original image and the artist’s usage of the image – Josh Azzarella’s Untitled #13 (AHSF) (2006).

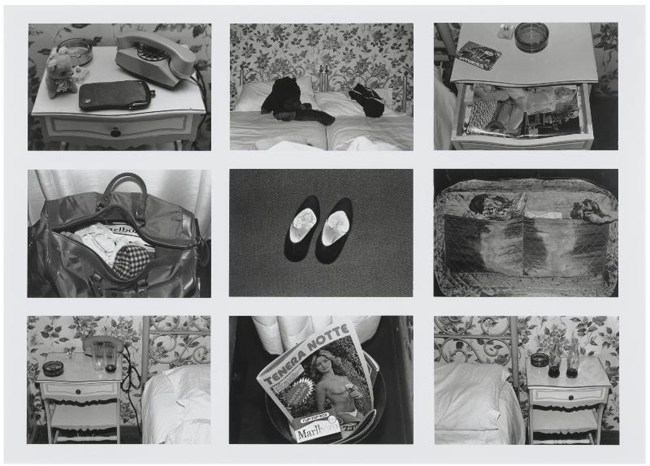

Sophie Calle. The Hotel, 1981. © Images are copyright of their respective owners, assignees or others

The Hotel

In order to produce the photographic series titled The Hotel, Sophie Calle spent a lot of time researching possible locations, writing texts, and actually taking photographs. In 1979, after being away from home for seven years, the artist returned to Paris. She felt lonely and unwanted, so she turned her attention to strangers. An obsession with the lives of people unknown to her lead Calle to take a trip to Venice where, in order to complete her project, she chose to work as a maid in a hotel. She spent her days investigating the lives of strangers – the artist researched their daily routines and habits, as well as inspected their personal possessions – Calle took numerous photographs of opened suitcases, bathroom accessories, and the wardrobes of people who stayed at the hotel.

After taking the photographs, Calle often wrote a little commentary for each of them, describing her sentiments regarding the objects that she managed to find whilst looking through the personal possessions of the hotel's guests. Not only did the artist hijack ones personal belongings, but she also used them for her project. The morality of Calle’s art project is really dubious, but the effect is definitely astonishing. Calle exhibited an associative link between hotel guests and the ordinariness of their valuables. In Baudrillard’s vocabulary, Calle used a basic reality to narrate similar, yet individual, stories of the people whom she had met in Venice.

Josh Azzarella. Untitled #13 (AHSF), 2006. Ed. 7+3a.p. Photo: joshazzarella.com

Untitled #13 (AHSF)

The artwork Untitled #13 (AHSF), by Josh Azzarella, is one of the digital prints that the artist produced as a response to the terrifying images from Abu Ghraib.

Abu Ghraib was a prison complex located in Iraq, close to Baghdad. It was built in 1950, and has been famously used by US-led coalitions. In January 2004, the Army Criminal Investigation Division reported shocking details of abuse and torture of Abu Ghraib prisoners by American troops – US soldiers had raped, stoned and mocked prisoners, without forgetting to take photographs of their horrific acts of torture. One of the most famous images shows an Abu Ghraib prisoner standing still on a narrow wooden box, with electric wires attached to his arms and genitalia. If the prisoner made any movement, he was immediately subjected to electric shocks.

An unidentified Abu Ghraib detainee, seen in a 2003 photo. (Associated Press)

In his artworks, Azzarella uses the images from Abu Ghraib, but alters them by removing the figures of the tortured prisoners. In this particular work, the artist removes the hooded figure so that all that is left in the image is a wooden box and the American torturer. Azzarella is questioning the importance of the absence of part of the image. By altering the original photograph, Azzarella is creating a separate political level. Firstly, he is questioning the memory of the spectator – the original images are extremely graphic and are difficult to forget. Secondly, he is questioning the importance of rancor – whether it is more important to remember the victim or the perpetrator. Finally, Azzarella is investing the importance of an empty space – this could only be compared to an eerie New York panorama without the Twin Towers.

The previous two examples are works of art based on borrowed histories, memories, and physical objects. They represent the artist’s desire to create new meanings and to construct new memories out of stories that belong to someone else.

To conclude, I could ponder whether the use of simulated, hyperreal images is good or bad, or whether it adds or reduces creativity and vision within visual cultures. But then, my argument would, as well, be dominated, predicted and eventually surrogated by the literature and visual material I have adopted. In lieu of this, I want to offer to the reader the following quote by Jean Baudrillard:

“We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.” [8]

My only hope is that the absence of a basic reality creates space for greater meaning and achievements.

[1] Jean Baudrillard, Simulations. New York: Semiotexte/Smart Art, 1983. p.2

[2] Ibid., p.11

[3] Ibid., p.11

[4] Ibid., p.12

[5] Ibid., p.25

[6] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books, 1969. p.6

[7] Damien Hirst, ‘We’re Here for a Good Time, Not a Long Time’, interview with Alastair Sooke, The Telegraph, 2011

[8] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994. p.79