Olympic Games of Art

Reportage from Art Basel 2016

23/06/2016

Photo: Elīna Norden

What joy to have, once again, found myself at Europe's most prestigious visual art event – Art Basel; and, as every year, I felt as if I were there for the first time...

From 16 to 19 June, the modern and contemporary art fair Art Basel gathered together, for the 47th time, leading art galleries from around the world in order to present the best of their collections on the international market.

The year has begun quite fortuitously for the Art Basel “family” in that, together with the Kickstarter community, they have developed a one-million-dollar co-financing foundation for non-profit projects. This support from small-scale donors proves that society trusts the competence of Art Basel in involving small players in the global art world, and in creating as many opportunities as possible for artists around the world. In addition, the Art Basel Cities project for urban areas has finally seen the light of day – its objective is to widen the horizons of Art Basel's sphere of activity by getting the organization involved in regional art events. Florence Derieux, the former curator of the PARCOURS sector of Art Basel, has now taken over the reigns as Curator of American Art at The Centre Pompidou Foundation; Derieux's baton has been given over to Samuel Leuenberger, who's latest showing indicates that he will continue with providing the public with a great PARCOURS program.

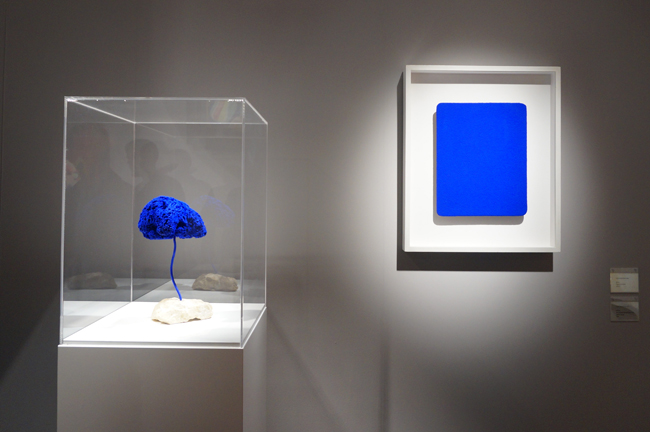

Yves Klein. IKB 34. Galerie Gmurzynska (Zürich)

Roy Lichtenstein. Brushstroke Head II. 1987. Richard Gray Gallery (Chicago/New York)

A first-class ticket to Basel

Every year, gallerists spend months planning ahead for their next showing in Basel. Specially-commissioned artworks, with which to surprise both the competition and potential clients, are kept tightly under wraps. What will be put on display is carefully thought out, and often requires a considerable dose of quality management. Only the most affluent galleries are invited to partake in these so-called “Olympic Games of Art”. According to the TEFAF art market report, income generated at art fairs accounts for up to approximately 40% of a gallery's yearly turnover. This year, more than 800 galleries competed for 300 spots at Art Basel. Those who qualify then continue to scramble for the best locations in the halls. Consequently, the galleries with the most advantageous placement gain an additional financial foothold, but also a symbolic one in terms of prestige.

Gallery_EstherSchipper(Berline).jpg)

AA Bronson. Folly. 2015. Gallery Esther Schipper (Berlin)

_JablonkaGalerie.jpg)

Eric Fischl. Tumbling Woman. 2015. Jablonka Galerie (Cologne)

During the planning stage, the team at the Dominique Lévy gallery (Geneva) discussed which shade of gray to use in the background for displaying Gerhard Richter's landscape, “Bonley-Landschaft” (1970). As Lévy herself explains, when planning the gallery's presentation, the smallest of details can have an immense effect on displaying the work successfully and attracting clients. And it is precisely this sort of attitude that becomes a commercial art gallery's key to success in moving out of the distant corners of the exhibition hall and into the spotlight where the most influential players on the art market all sit. In the case of the Dominique Lévy gallery, they got themselves a spot right across from the New York contemporary art gallery David Zwirner, and London's Helly Nahmad.

_Gallery_DominiqueLevy(Nujorka).jpg)

Gerhard Richter. Bonley-Landschaft. 1970. Galerija Dominique Lévy (New York/London/Geneva)

_MarianGoodmanGallery.jpg)

Giuseppe Penone. Spined Dacacia. 2005. Marian Goodman Gallery (Paris/New York/London)

No one owns the sun. It shines upon all of us.

Visitors to Art Basel were first greeted by the alternative life-space “Zome Alloy”, its futuristic forms rising from the square in front of the fair much like mushrooms after a summer rain. (Yes, this year the rain did a good job of washing and rewashing the festival's flags and banners...)

Oscar Tuazon. Zome Alloy. 2016

A spike in environmental problems, along with recent human mass-migrations, has brought to the forefront the subject of modular design possibilities. Oscar Tuazon, the American artist behind “Zome Alloy”, poses the question of – What can a home do? Can it also be a sculpture? Can people live in an artwork?

The original idea for the “Zome” U-shaped cluster of structures came from Steve Baer, an American eco-architect and solar engineer. From 1969 to 1972, using mathematical coherences, Baer constructed the first modular passive solar home – “Zome House” – as a family home in the New Mexico dessert; he still lives there today.

This latest version by Tuazon, “Zome Alloy”, has been built on the exact same scale as Baer's “Zome House” (1972). During Art Basel, the “Zome Alloy” installation hosted the second-ever “Alloy Conference” – a series of talks and discussions on energy, alternative materials, and modular construction; Steve Baer organized the first such conference in New Mexico, in 1969.

The organizers of Art Basel actively encouraged fair-goers to take selfies with this highly Instgram-able architectural object, so that long after the fair, Tuazon's question of What can a house do? continues to resonate on the social networks of the interweb.

Which of Latvia's closest neighbors presented at Art Basel?

In the STATEMENTS section of the fair, both the Johan Berggren Gallery (Malmö) and Galeria Stereo (Warsaw) presented for the first time. The gallery Bo Bjerggaard (Copenhagen) was part of the FEATURE section, while the Niels Borch Jensen gallery (Copenhagen, Berlin) showed in the EDITIONS section.

_Gallery_I8(Reikjavika)%20(1).jpg)

Birgir Andresson. All This And The Earth As Well, 2005. Galllery I8 (Reykjavík)

_GalleriNilsStaerk.jpg)

Dario Escobar. Obverse & Reverse XXVIII. 2016. Nils Staerk Gallery (Copenhagen)

Just like last year, the main gallery sector featured the following galleries: Nicolai Wallner (Copenhagen), Nils Stærk (Copenhagen), Andréhn-Schiptjenko (Stockholm), Nordenhake (Stockholm, Berlin), Standard (Oslo), Gerhardsen Gerner (Oslo, Berlin), 8 Gallery (Reykjavik), Starmach (Krakow), and Foksal Gallery Foundation (Warsaw).

How much? – A tactless question

Art Basel is enveloped in glamour; people drink sparkling wine and celebrate. But what, exactly, are they celebrating? After all, Art Basel is an art fair in which only the works of the most legendary, most ambitious, and most crazy artists end up – and which only the elite can afford to buy.

_Marlborough.jpg)

Juan Genoves. Fractal. 2015. Marlborough Gallery (New York/London/Madrid/Barcelona)

Gallery_Hauser&Wirth.jpg)

Louise Bourgeois. Love, 2000. Hauser & Wirth Gallery (Zürich/London/New York/Somerset/Los Angeles)

Speaking about the prices of artworks in public is frowned upon, and there are no visible price tags. The art market possesses an aureole of secrecy; there are more questions about the selling of art than answers are given out. Perhaps it is this bluestocking-, bourgeois-behavior that makes the event so alarming. As soon as too much attention is brought to the transaction aspect, the direct representative of the artwork – the gallerist – becomes extremely sensitive. Of course, price tags, as such, do not exist; that’s so that the aesthetic performance of the artwork does not have to be confronted with its expression in monetary terms. Here, the transaction is only discussed with potential buyers behind closed doors, and often times, the amounts don't adhere to the ones previously released by the gallery.

_GalleryHauser&Wirth.jpg)

David Smith. Anchorhead, 1952. Hauser & Wirth Gallery (Zürich/London/New York/Somerset/Los Angeles)

_Gallery_Hauser&Wirth.jpg)

Vija Celmins. Sea Drawing with Whale, 1969. Hauser & Wirth Gallery (Zürich/London/New York/Somerset/Los Angeles)

The gallery Hauser & Wirth claimed the biggest star of the show – “Anchorhead” (1952), by the American sculptor David Smith – which went for seven million dollars. Both “Memory Ware Flat #10”, a collage by Detroit punk-artist Mike Kelly, and “Sea Drawing with Whale”, by Latvian-born artist Vija Celmins, went for 1.5 million dollars each. Paul McCarthy's sculpture, “WS, White Snow Flower Girl #3” (2016), was sold for 575,000 dollars.

Mike Kelly. Memory Ware Flat #10, 2001. Hauser & Wirth Gallery (Zürich/London/New York/Somerset/Los Angeles)

Paul McCarthy. WS, White Snow Flower Girl #3, 2016. Hauser & Wirth Gallery (Zürich/London/New York/Somerset/Los Angeles)

Gerharden Gerner gallery (Oslo, Berlin) let it be known that “Untitled (20)” (2016), by Magnus Plessen, was bought for 130,000 EUR by an Indonesian collector.

Due to the entrance of new collectors into the market, photography is experiencing a rise in prices, and only just now finding itself on par with painting and sculpture. The James Fuentes gallery showed five photographs by Jonas Mekas (the Lithuanian-born godfather of American avant-garde film) which were taken during Mekas' imprisonment in a Nazi labor camp in Germany. The photographs were priced at 10,000 EUR a piece.

_GalleryGerhardsenGerner.jpg)

Andreas Slominski. XYZ Nature VOL525, 2011. Gallery Gerhardsen Gerner (Oslo/Berlin)

Cindy Sherman. Untitled, 2016. Metro Pictures (New York)

Cindy Sherman's large-format photographs were shown by the Metro Pictures gallery, and priced at 250,000 to 375,000 dollars. “Untitled #108” was sold for 250,000 EUR.

A print of “Aletschgletscher” (1993), by Andreas Gursky, was sold by Sprueth Magers gallery for 450,000 EUR.

_GoodmanGallery.jpg)

Walter Oltmann. Catterpillar Suit IV, 2016. Goodman Gallery (Capetown/Johannesburg)

_GallerieThomasSchulte.jpg)

Alice Aycock. Waltzing Matilda, 2012. Galerie Thomas Schulte (Berlin)

UNLIMITED, without limits

Curated by Gianni Jetzer, the UNLIMITED sector featured 88 ambitiously large-format projects. This sector first appeared in 2000, to hold all of the artworks that either could not fit into the regular gallery stands, were too loud, emitted a strong smell, or made use of live flames – basically, anything that would hinder the work of neighboring stands.

Gallery_neugerriemschneider(Berline).jpg)

Ai Weiwei. White House, 2015. Galerie neugerriemschneider (Berlin)

_Gallery_GladstoneGallery(Londona).jpg)

Anish Kapoor. Dragon, 1992. Gladstone Gallery (London). Art Basel Unlimited

The artworks in UNLIMITED are diverse – some step out of their frames, some shoot high up into the air, and others require the viewer to enter its context and see the invisible. Ai Weiwei, Elmgreen & Dragset, Tracey Emin, Kader Attia, Jannis Kounellis, Paul McCarthy, Frank Stella, Hans Op de Beeck, and James Turrell, among others, have works in this section of the fair.

_Gallery_Sprovieri(Londona).jpg)

Jannis Kounnelis. Untitled, 2014. Gallery Sprovieri (London). Art Basel Unlimited

(2010)_Gallery_JackShainmanGallery(Nujorka).jpg)

El Anatsui. Gli (Wall). 2010. Jack Shainman Gallery (New York)

New York’s Jack Shainman Gallery showed five monumental curtains, “Gli (Wal)” (2010), by El Anatsui. As one could expect from Anatsui, the works were made of simple and inexpensive materials – bottle caps and aluminum cans.

Gallery_TheApproach(Londona).jpg)

Heidi Bucher. Bellevue. 1988. The Approach Gallery (London). Art Basel Unlimited

Gallery_galerie_frank_elbaz(Parize)+GagosianGallery(Nujorka).jpg)

David Balula. Mimed Sculptures, 2016. Galerie Frank Elbaz (Paris), Gagosian Gallery (New York). Art Basel Unlimited

In the performance “Mimed Sculptures” (2016), by French artist David Balula, silent sculptors wearing pink gloves “kneaded” and “sculpted” thin air into invisible sculptures. The piece was highly reminiscent of Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale, “The Emperor's New Clothes”, in which swindlers “sew” a new set of invisible clothes for the king. According to the work’s description, the mimes performed the making of Alberto Giacometi's sculpture “Le Nez” (1947), Louise Burgeois’s “Unconscious Landscape” (1967-68), and Henry Moore’s work in bronze, “Reclining Figure: Hand” (1979).

_Gallery_MarrianneBoeskyGallery(Nujorka)3.jpg)

_Gallery_MarrianneBoeskyGallery(Nujorka)5.jpg)

Hans Op de Beek. The Collector’s House. 2016. Marianne Boesky Gallery (New York)

Belgian artist Hans Op de Beek created an ambiance worthy of Stanley Kubrik, one in which everything – the walls, the paintings, oranges... even a dog – have lost their color. Titled “The Collector’s House” (206), the piece is entirely gray and muted. A certain word pops into mind when one looks at the space that Op de Beek has created – mausoleum. The gray walls absorb any and all sound, and the black waters of the atrium's pool swallow-up one's reflection. Everything – all of the furnishings (furniture, books, a piano), and the beautiful sirens, children, and a dog – are as frozen and ashen as the victims of Mt. Vesuvius at Pompeii.

Gallery_DanielTemplon(Brisele)2.jpg)

Chiharu Shiota. Accumulation Searching for Destination, 2014. Daniel Templon Gallery (Brussels)

_Gallery_AntonKernGallery(Nujorka)2.jpg)

(Detail.) Chris Martin. Untitled, 2016. Anton Kern Gallery (New York)

Gallery_ChemouldPrescottRoad(Mumbai)3.jpg)

Mithu Sen. Museum of Unbelongings. MOU, 2016. Chemould Prescott Road Gallery (Mumbai). Art Basel Unlimited

Down the PARCOURS paths, alongside the banks of the Rhine

Nineteen site-specific artworks were set up in the open-air PARCOURS sector of Art Basel. The objects were scattered throughout the historic center of Basel – along the banks of the Rhine River, next to the Cathedral in Old Town, and in the tunnel passing underneath the Les Trois Rois hotel.

_Gallery_DavidKordnsky(Losandzelosa).jpg)

Andrew Dadson. Painted Plants, 2015. Gallery David Kordansky (Los Angeles). Art Basel Parcours

Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar's public intervention, “The Gift” (2016), brought attention to the true difficulties of life. Volunteers handed out to viewers gifts from the artist – little blue cardboard boxes. The instructions on the box requested that the receiver of the box unfold it and then put it together again inside-out, thereby transforming the plain box into a charity collection box.

Alfredo Jaar. The Gift, 2016. Goodman Gallery (Capetown/Johannesburg), Galerie Thomas Schulte (Berlin)

_Gallery_BlumAndPoe(Nujorka)2.jpg)

Sam Durant. Labyrinth, 2015. Blum and Poe Gallery (New York). Art Basel Parcours

In his multimedia works, the American artist Sam Durant takes a look at various social, political and cultural issues. The installation “Labyrinth” (2015) reflected Durant's thoughts on freedom and imprisonment, movement and stagnation.

“The Toilet on the River” (1996-2016), a “metaphysical and philosophical” outhouse on the banks of the Rhine, was the creation of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. It was meant to engage two human meditative states: sitting on the toilet, and admiring a natural landscape.

Gallery_Sapoveri(Londona)1%20(1).jpg)

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. The Toilet on the River. 1996–2016. Gallery Sapoveri (London). Art Basel Parcours

_Gallery_VonBartha(Basel)2.jpg)

Bernar Venet. Effondrement Arcs. 2016. Gallery Von Bartha (Bāzele). Art Basel Parcours

Art Basel in the time of selfie-sticks

The interactions between Art Basel's 645,000 followers on Instagram can be seen every week on the art fair's Facebook page, where the best images taken by Instagramers are published under the #artbasel hashtag.

Jeff Koons. Wall Relief With Bird, 1991. Mnuchin Gallery (New York)

Sherrie Levine. Steer Skull, 2002. Jablonka Galerie (Cologne)

There are two characteristics which almost all of the most-photographed objects possess at least one of – either the artwork is impressively huge, or it has a mirrored surface. Both features serve as ideal backgrounds for selfies. Square subjects are ideal material for Instagram. Marc Spiegler, Director of Art Basel, isn’t exactly keen on this phenomenon, saying that if it were in his powers, he would ban the taking of selfies at Art Basel events in Hong Kong, Miami and Basel. It is his opinion that the public’s attention becomes attuned to getting the perfect selfie instead of immersing oneself in the artwork itself. No artist is happy about his or her work having a secondary role as an effective background for a selfie. Nevertheless, gallerists deny that they plan out their displays so that they will look good on social networks, and they maintain that artists do not create Instagram-friendly works on purpose. At the fair, every glimmering sculpture by Jeff Koons, Damian Hirst and Anish Kapoor had at least one, if not two, gruff-looking security guards standing watch, seemingly able to read your thoughts even before you could manage to pull out your phone. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that the viewing public’s energetic use of social media sites benefits both the galleries and the artists – and grandly, at that. Even now, days after the closing of Art Basel, images and memories of it continue to flood the internet accounts of its fans.

_GalerieThomasSchulte%20(1).jpg)

Idris Khan. Six Years, 2016. Galerie Thomas Schulte (Berlin)

An art marathon and running shoes

For some, Art Basel may symbolize the excitement of wheeling and dealing in art, but for most of its fans, it is a week-long marathon of art exhibitions. In the heat of the fair, gallerists barely have a moment to take a break, and the women – all in high heels – never sit down. Gallerist Dominique Lévy maintains that the wearing of elegant shoes shows respect to the clients; she says that she cannot present an artwork to a client if she’s wearing low-heeled shoes.

Gallery_NicolasKrupp.jpg)

Werner Reiterer. Euer Anker Ist Mir Wasser, 2015. Nicolas Krupp Gallery (Basel)

In much the same way, non-purchasing fair-goers also realize the importance of selecting the right shoes one wears to the fair. Unlike at the Cannes Film Festival – where the fashion police fiercely look down at the occasional Hollywood actress who refuses to wear heels, or even at Larry Gagosian, who at last year’s festival wore Converse sneakers with his tuxedo – at Art Basel there’s an unwritten rule of etiquette that one should be pragmatic and think about the hours that will be spent walking along the labyrinths of galleries at the fair. Consequently, the public at Art Basel can be seen following a unifying and healthy fashion trend – the wearing of long-distance running shoes. And in the ladies’ room, any and all differences between the cream of society and the average viewing public disappears, for we are all equal when suffering from blistered feet; sometimes, a band-aid can be worth more than a Gerhard Richter abstract.

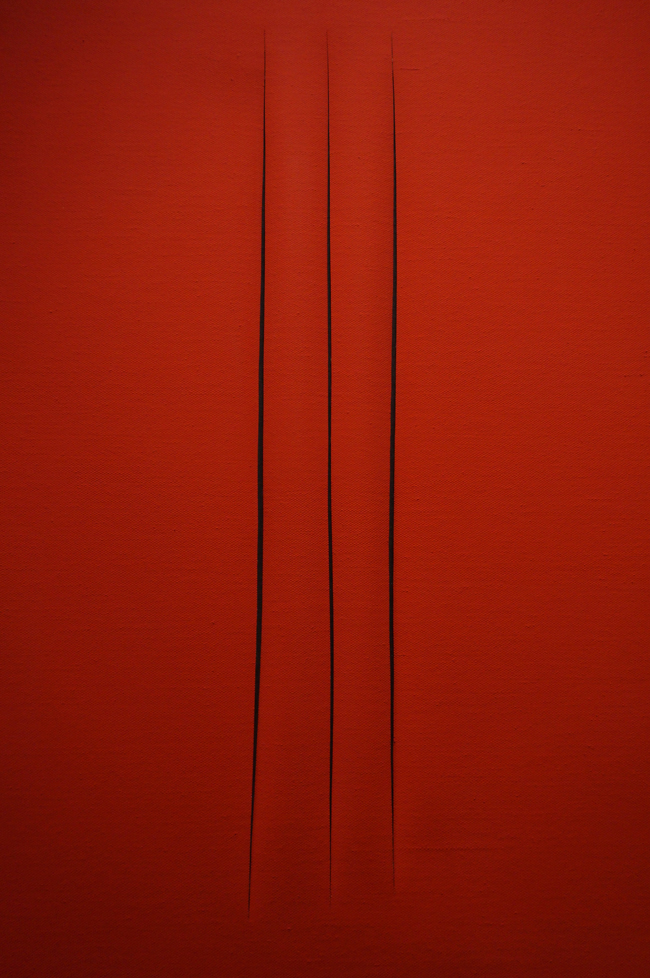

Lucio Fontana. Concetto Spaziale, Altese, 1967. Richard Gray Gallery (Chicago/New York)

GalerieBarbaraTumm(Berlin).jpg)

Anna Oppermann. Ensemble. Portrait No 3, 1985. Galerie Barbara Tumm (Berlin)

Gastronomy and art

A multitude of collateral events swirl around Art Basel – such as Liste, Scope, Volta, Design Miami, etc. – and all of their event dates overlap. It follows that when going to Art Basel, one must not forget to take along water and whole-grain snacks, for there is little time in which to see so much. Food always tastes much better when eaten out in the open air, as everyone knows, but how close are gastronomy and art? It turns out that the finery of Art Basel also extends beyond its gallery stands, and into the world of the culinary arts…

For only the period of Art Basel, the local art gallery Von Bartha settled into an 850-square-meter space that used to be a petrol station and garage, and much to the perplexity of passersby and drivers, set up a pop-up restaurant. Here a team from the Basel restaurant Rhyshänzli offered-up traditional Swiss foods such as cheese platters and so on. On display in the pop-up restaurant were works by Swedish artist Christian Andersson.

_Gallery_JamesFuentes(Nujorka).jpg)

Alison Knowles. Make a Salad, 1962. Gallery James Fuentes (New York). Art Basel Unlimited

Fifty-four years after the debut of her installation “Make a Salad” (1962), the 82-years-young Fluxus performative art pioneer Alison Knowles (1933) demonstrated how to put together a salad in the UNLIMITED sector of the fair. This, however, was not a regular salad with a simple recipe: iceberg lettuce leaves were scattered on a green drop-cloth on the floor, and the public watched as Knowles meditatively chopped the lettuce leaves. Once that was done, the public was invited to participate in the performance by helping the artist “toss” the salad up into the air.

_Gallery_Lisson_Gallery(Londona)2.jpg)

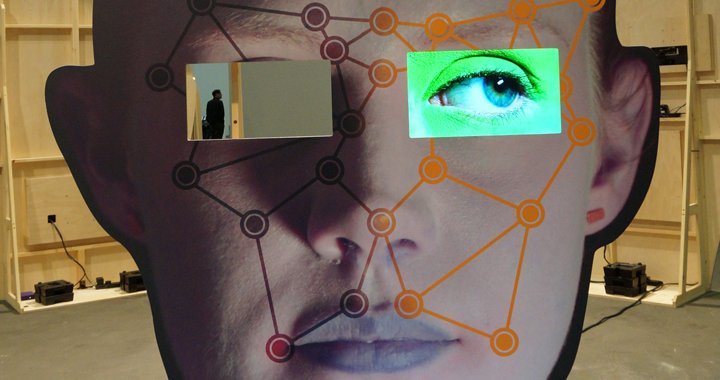

Tony Oursler. template/variant/friend/stranger, 2014. Lisson Gallery (London). Art Basel Unlimited

_RichardGrayGallery.JPG)

_Gallery_HauserAndWirth.JPG)

_Gallery_Hauser&Wirth.JPG)

_MetroPictures(Nujorka)2.JPG)

_GoodmanGallery(Keiptauna)_ThomasSchulte(Berlin).JPG)

_MnuchinGallery.JPG)

JablonkaGallerie.JPG)