Art roads lead to Athens

05/07/2016

It’s 42°C in Athens, the cobblestones are hot as sauna stones, and the wind that blows down from the Acropolis feels like a hot hair dryer. But neither the heat nor the seemingly oversaturated summer art calendar deters the crème de la crème of the global art scene (from Maurizio Cattelan, directors of prestigious museums and art collectors to the prominent Austrian gallery owner Thaddaeus Ropac) to touch ground in Athens’ swelter just a few days after Art Basel, Zurich’s Manifesta and the uproar caused by Christo’s installation in Italy. Therefore, any envy of Athens is completely justified.

Actually, the heat has only been this extreme for the last couple of days, says Helga Christoffersen, a curator at New York’s New Museum. We happen to share a taxi on our way to the Benaki Museum, where international art specialists and journalists are being given a private viewing of the Equilibrists exhibition that opened a couple of days earlier. The exhibition focuses on new Greek art, and Christoffersen is one of its three curators, together with her New Museum colleagues, artistic director Massimiliano Gioni and curator Gary Carrion-Murayari. When I meet Gioni a short while later in the entrance hall of the Benaki Museum, carrying a young child on his shoulders and standing next to a baby carriage, he admits that this time most of the hard work was carried out by his team. Christoffersen was also his assistant curator for the Encyclopedic Palace exhibition at the 55th Venice Biennale as well as the coordinator for Denmark’s pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale.

The Equilibrists. Installation View. Benaki Museum, Pireos St., Athens. Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras and Rebecca Constantopoulou

The Equilibrists project officially began as a collaboration between the New Museum, the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art and the Benaki Museum. But it is in fact the result of a purposeful private initiative that has been going on for the past 33 years. The DESTE foundation, which has this year reached the age Christ was at the time of His death, was initiated and established by the Greek art collector, industrialist and philanthropist Dakis Joannou. As one of contemporary art’s most exciting visionaries, Joannou’s name shows up on a number of prestigious museum boards and has been on the ArtReview Power 100 list of most influential personalities in the art world since its very inception. Although his collection contains works by many international mega stars (Matthew Barney, Jeff Koons [whom he began collecting at the very beginning of Koons’ career], Maurizio Cattelan, Urs Fischer, Robert Gober, Gabriel Orozco, Paul McCarthy, Christopher Wool and others), Joannou has always been an active supporter and promoter of the local Greek art scene.

In Greek, the word “deste” means “look”, and the foundation thereby literally encourages people to look, notice and take note. So it’s also natural that The Equilibrists – one of the cornerstones of this anniversary year for the foundation – is dedicated specifically to Greek art. And not its history, but rather its future. The exhibition features 33 young artists in their 20s and 30s who are of Greek heritage and hail from Greece as well as Cyprus, London, Berlin and New York. It is crucial for these artists, who are a part of the so-called “young precariat” generation, to be noticed and evaluated. They have grown up in an era of political and economic instability, an instability that has only increased in the past decade. The Equilibrists is a story about their outlook on life and the challenges they face in a world that is becoming more complicated by the day. For them, life sometimes really feels like juggling on a tightrope.

And actually, juggling as an acrobatic discipline can trace its roots back to Ancient Greece. Even though the term itself was introduced only in the 18th century, acrobats juggling while on a tightrope were depicted in Classical Greek art at least as early as 300 BCE. As Carrion-Murayari, who is the Kraus Family Curator at the New Museum, writes in the exhibition catalogue: “This exhibition of young Greek and Cypriot artists borrows this term, not to denote an overall theme of acrobatics, but rather to express a shared sensibility of poise and skillfulness and a common ability to wrest a sense of balance and stability from a tumultuous, entropic world.”

The Equilibrists. Installation View. Benaki Museum, Pireos St., Athens. Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras and Rebecca Constantopoulou

Christoffersen explains that work on the exhibition lasted about one year. Of course, potential participants had already been considered beforehand, although she says this was not an easy process. The curatorial team first selected 100 artists from the 500 applications they had received. Then the New Museum curators spent most of their time on the road, visiting studios and personally meeting artists, until they finally agreed on 33 artists. Christoffersen admits that one of the biggest surprises for her – and also the artists themselves – was the fact that this event was the first time that some of the participants, who live all across the globe, found out about and met each other. The exhibition can thereby be considered the concentrated essence of the new Greek art scene in both a literal and figurative sense.

Considering Greece’s national debt and also the current refugee crisis (which, among other things, is at the centre of Ai Weiwei’s large exhibition currently on show at the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens), one could expect that the exhibition’s thematic vision might have a fairly pessimistic mood. On the contrary, however, the young artists speak about acute problems like mature individuals, all the while preserving a sense of humour and positivity. And, even though life has carried the artists to all corners of the world, their art nevertheless rests on a foundation of Greek history and cultural traditions, upon which their future visions are also being built.

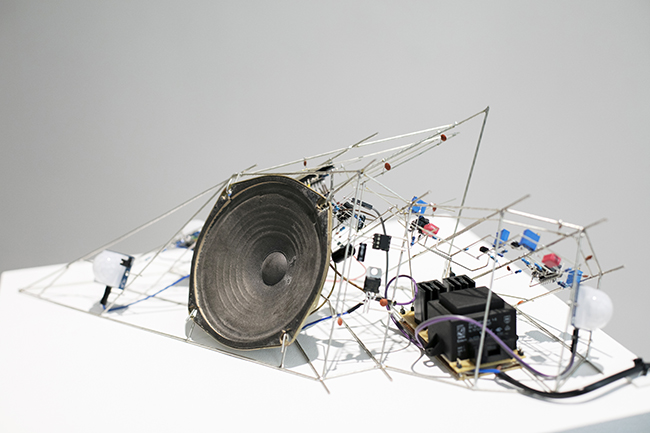

For example, the kinetic installation Pieces of a Clash by Giorgos Gerontides (born in 1987, lives and works in Thessaloniki) – in which, like a child’s wind-up music box, some mythical “motor” has been set in motion and proceeds to turn a whole mechanism of emotions made up of a fan and seemingly useless objects and memories that have most likely been thrown into the rubbish bin – will bring a sentimental smile to those who grew up in the hot southern lands. For those born in Greece and Turkey, a fan provided not only physical relief from the sweltering heat but also served as a toy – similarly to wooden hobby horses in other countries. Children decorated fans with feathers and other objects found in their building’s courtyard; when plugged in, the fan became a colourful “eternal motor” for their childhood dreams.

The Equilibrists. Installation View. Benaki Museum, Pireos St., Athens. Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras and Rebecca Constantopoulou

Or Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos’ (born in 1989, lives and works in Athens) work Silent Hysteria, the laconic design of which is quite hypnotising. As the artist explained when I met him at the exhibition, the foundation for his work consists of three things: his interest in modernist architecture, the Russian avantgarde and Greece’s symbolic dream for the future, namely, its hopes of discovering oil. Daskalakis-Lemos’ father worked in the petroleum industry, and he says that – like many other Greeks – his father still hopes that their country will discover oil, thereby solving Greece’s deep economic troubles. Daskalakis-Lemos’ work is undeniably one of the most powerful in the exhibition and receives many lingering looks. It is centred around a black, shiny field of oil on the floor, inspired by Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (Malevich was a Russian avantgarde artist and the originator of Suprematism). The artist has used real oil in the artwork, and there’s a layer of water under the oil. If a more hefty visitor to the exhibition jumps up and down on the museum’s parquet floor, the square of oil on the floor comes to life and begins to sway. For its part, the large photograph on the wall of an oil explosion makes visitors ponder the damage that “black gold”, the potential economic saviour, does to the environment.

Kallinikou Stelios. Bricks from the series Local Studies. The Equilibrists. Benaki museum. Athens Publicity photo

Local Studies, a series of photographs by Stelios Kallinikou (born in Cyprus in 1985, lives and works in Nicosia), documents the artist’s daily journeys in the world’s only still-divided capital, Nicosia. Through these photographs, he tries to find the things that are shared on both sides, thereby disassociating himself from the political borders that separate the part of the island under Greek jurisdiction and the part occupied by Turkey. Even though the peace talks begun this year between Cyprus’ Greek and Turkish sides offer hope that Nicosia’s “green line” will eventually fall, just like the Berlin Wall before it, Cypriots I meet in Athens say that this is not the first attempt at peace talks...nor will it most likely be the last.

Malvina Panagiotidi’s (born in Athens in 1985, lives and works in Berlin) work Ghost Relief, which serves as the symbolic beginning of the exhibition, portrays the façades of abandoned, purportedly haunted houses in Athens. The paraffin models bring to mind the inevitable ruthlessness of time and the unavoidable changes it makes to the urban environment.

Asked to compare today’s young artists with the artists who 30 years ago formed the foundation of his art collection – in other words, how similar or different are their approaches to art and life, and how similar or different are the themes they speak about through their artwork – Joannou says: “One big difference is connectivity. Through the Internet and affordable travelling, today’s artists are more connected and more aware. They have digested the past, they understand the present and look to the future. The earlier generation was trying hard to connect and understand the present; they were struggling with the past and with history, leaving them little time to deal with the future.”

The Equilibrists. Installation View. Benaki Museum, Pireos St., Athens. Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras and Rebecca Constantopoulou

In addition to all its artistic and conceptual qualities, The Equilibrists is a vivid testimony to the significance of private partnership in the development of a local art scene. It not only provides an insight into Greece’s current new art scene; with the care of the DESTE foundation, the exhibition has also managed to garner the attention of the international art elite. It thereby boldly puts Athens and young Greek artists on the global map.

Furthermore, in 2017 Athens will also become the second home to documenta. The 100-day exhibition, which has taken place every five years since 1955 in the German city of Kassel, will begin in Greece in April of next year.

Read in the Archive: An interview with Greek collector Dakis Joannou

I ask Joannou how, looking back over the past 33 years, the role and power of non-profit art foundations like DESTE have changed compared to the institutional art scene. Also, what does he believe is DESTE’s main mission over the coming five and ten years? He answers: “In the early 1980s, Iolas* cast a large shadow, and there were a couple of institutions collecting Greek artists. Today there are tens of collaborative non-profit spaces, there are a couple of non-profit foundations, and the Museum of Contemporary Art is about to open. DESTE, as usual, has only short-term plans responding to current issues. In the fall we’ll have a show with the Benaki Museum of George Lappas, an important Greek artist who died prematurely earlier this year, while for the spring of 2017 we are preparing a show of previous DESTE Prize winners at the Museum of Cycladic Art to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Prize. In 2017, we’ll also have a show entitled Liquid Antiquity, organised in collaboration with Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Princeton University’s Department of Classics and hosted at the Benaki Museum, a Kara Walker exhibition at our Project Space on Hydra island, a presentation of the destefashioncollection project at the Bass Museum of Art in Miami, and an exhibition with works from the Dakis Joannou Collection at the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle in Berlin set to open in the fall of 2017.”

Disconcerting mattresses

Joannou has always had a special ability to notice new names, and he’s also famous for his habit of constantly moving around and rearranging the artwork he has at home and in his office. He manipulates artwork like a magician, knowing full well that, depending on where a person sees a piece of artwork, his or her reaction may be fundamentally different. One site for Joannou’s experiments is the private gallery space on the lower floor of his house. As a part of the DESTE events, most of it was devoted to the American artist Kaari Upson (1972), the walls decorated with her large-scale mattress installations. Needless to say, not all of those present at the gallery recognised the artist. But, as several people familiar with the art world said, that’s nothing to be ashamed of in the professional realm. Joannou had provided a surprise for the audience! Although, when out of curiosity I posed this question to Maurizio Cattelan, he answered immediately, “It’s Kaari Upson.”

Although externally decorative and sometimes even resembling gigantic, exotic silicon and latex flowers, Upson’s mattresses are actually startlingly intimate and sometimes unleash quite uncomfortable feelings and emotions. Like finding a keyhole to the most secret rooms of one’s subconsciousness, one is tempted to take a peek inside...but the scene is ghastly. And even though these installations are only replicas of used mattresses, they nevertheless still seem to retain the impressions of their former user’s bodies. Ecstacy, death, rest after a day’s work, feebleness. It is seemingly easy to identify with Upson’s mattresses – they hypnotically pull the viewer in, at the same time bringing to the surface a most perverse bouquet of emotions, memories and fantasies. Take, for example, the gigantic urethane and aluminium mattress with a hole in the middle – at first it looks like a red-yellow-blue flower, but, upon a closer look, it begins to resemble genitalia. And, like the density of experience accumulated by any well-used mattress, this work’s title, Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue (2014), is an obvious paraphrase of Barnett Newman’s legendary series of four large-format paintings (1966-1970) of the same name, which was in turn adopted from Edward Albee’s play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? In fact, two of the paintings in Newman’s series were vandalised in attacks in museums. The Who’s Afraid... series of paintings have practically become icons in the art world and have been subject to a variety of interpretations by other artists.

The mattress is a favourite and apt metaphor in art, allowing the viewer to delve into the depths of his or her subconsciousness (which rarely bears resemblance to a feather bed) without physical touch or the intercession of a psychotherapist. Last year, the Sprüth Magers gallery in Berlin (which also represents Kaari Upson) hosted an exhibition of drawings titled Metro Mattresses by Upson’s fellow Angeleno and pop art pioneer Ed Ruscha. He took inspiration from abandoned mattresses he had found on various street corners of Los Angeles. Under Ruscha’s direction, they became intimate, multi-layered and at times acutely exposed metaphorical stories about dreams, passions and the unrelenting pace of a person’s life. As Ruscha stated in the exhibition’s press release, “The mattresses become not just litter in the landscape but more like scary animals.” The same could be said of Upson’s works.

Invasion of crabs

A similar story about destruction and the inevitable disintegration of everything can be found in the Putiferio exhibition by Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi, which opened with a full-moon performance at DESTE’s Slaughterhouse art space on the island of Hydra.

In the summer heat just before Midsummer, Cuoghi turned the area around the former slaughterhouse into a surreal kiln, with ceramic ovens of various forms and sizes smoking all around. The process brought to mind a unique sacrificial ceremony, with the audience also playing a part in the ritual that balanced on the fragile border between the divine and diabolical. In Latin, putiferio can also mean “chaos” or a “small hell”. When Cuoghi arrived on Hydra in January of this year in order to develop the idea for the exhibition, the former slaughterhouse building was full of wasps’ nests. He felt unwelcome, unwanted and unnecessary amidst the assault of wasps, and thus he got the idea for a symbolic invasion of crabs. The kilns, fuelled with firewood, garbage and all other manner of flammable materials, “birthed” the crabs with unflagging intensity throughout the evening. The ceramic creatures in various forms and colours then “invaded” and occupied the space inside the former slaughterhouse, forming all sorts of associations – from current geopolitical issues to the goblins in our subconscious minds. With the full moon gleaming above the Aegean Sea, the air was heated by both nature and Cuoghi’s kilns, while the artist and two assistants in brightly-coloured gloves bustled about like unearthly alchemists.

In response to the comment “What a crazy project”, Cuoghi (long lost in the trance of artistic creation, a water bottle in one hand and a fire poker in the other) just said, “I’m a crazy person, too.”

Cuoghi is also represented in Joannou’s art collection and is one of the collector’s favourite artists. Last year the artist curated the Ametria exhibition at the Benaki Museum, which was organised in collaboration with the DESTE foundation. The idea of continuous transformation and changes is one of the main themes in Cuoghi’s art. One particular performance of his has already become a thing of legend – in it, the artist outpaced time and portrayed his own father. He began the performance in 1998, at the age of 25, and continued it for several years. During that time, Cuoghi gained weight, grew a long beard, and began dressing and behaving like his father, thereby almost physically knocking down the border between reality and fiction. True, this project cost the artist quite dearly – when, after his father’s death, Cuoghi wished to return to his natural role in life and time, the process ended up being painful and slow and even required surgical intervention. But even the surgery was later transformed into art.

Cuoghi’s Putiferio project, for its part, continues a tradition established by DESTE in 2009, namely, each year devoting the former slaughterhouse to a single artist or artists’ group as a home to a work of art created specifically for the space. Previous artists have included Urs Fischer, Matthew Barney, Maurizio Cattelan, Doug Aitken, Pawel Althamer and Paul Chan.

Hydra, located a mere 1.5-hour ferry ride from Athens, is considered one of the country’s most romantic islands and has long been a favourite relaxation spot for Greece’s aristocracy. Its popularity only grew in the 1950s, when Boy on a Dolphin (1957), with Sophia Loren in the leading role, was filmed there. It was the first film in which Loren spoke English and also the first Hollywood film to be filmed in Greece.

A trip to Hydra is like travelling back in time. There are no automobiles on the island, nor are there any bicycles, due to the steep and cobbled roads. The only forms of transportation here are walking, riding a donkey (there are over 500 of the animals on the island) or water taxi. But it usually only takes visitors a very short while to adjust to the much slower and calmer rhythm of life. Because the island’s historical heritage is carefully preserved, there are also no new, modern buildings on Hydra, and life mostly centres around the marble-paved port and the quaint nearby streets. Most of the houses are not numbered, because there’s simply no need for it. There’s also no need for a map, because it’s almost impossible to get lost in Hydra town – everyone here knows each other, and visitors feel like they’ve arrived into a large Greek family. When Joannou’s yacht, the Guilty (which is painted with camouflage by Jeff Koons), arrives in Hydra’s small harbour, it marks the symbolic beginning of summer and the culture season. Glamorous international guests as well as locals and tourists to the island are all welcome at exhibition openings at the DESTE Project Space Slaughterhouse, giving the events a truly diverse feel.

The almanac of DESTE’s anniversary

An 868-page book, titled DESTE 33 Years: 1983–2015, has also been published in honour of DESTE’s 33rd anniversary. The substantial volume is at once an art object, historical testimony, a source of inspiration, a social sculpture...the descriptions could fill a whole page. But, most importantly, it gives readers a glimpse into a creative process that has lasted for 33 years, as well as an authentic sense of being right there alongside it. Personal photographs, transcripts of conversations and newspaper cuttings are interspersed with photos from exhibitions and the preparatory phases thereof. The book covers everything that has happened at DESTE over the 33 years of its existence: solo exhibitions and group shows that later travelled to several museums, the DESTE Prize established in 1999 with the goal of supporting contemporary art in Greece, the projects on Hydra, over 100 publications and exhibition catalogues published by DESTE and so on. Page through the book, and, given the concentration of energy contained in its pages, at times you might even feel like it’s a living organism.

Read in the Archive: Summer programme 2015 of the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art

The book begins with an introduction by Joannou in which he tells about his first encounter with art. While studying at Cornell and Columbia universities in New York, he witnessed the heyday of pop art; inspired by Jasper Jones and all of what was going on at the time, he even created his own readymade as a gift for a friend. Later, at the University of Rome, Joannou earned a doctorate in architecture and also performed his last attempt at creating art, namely, placing a Dunhill pipe (a favourite of both Joannou and Marcel Duchamp) on top of a Coca-Cola bottle painted white, or, as he called it himself, The “Duchamp” Pipe Atop a “Warhol” Coke Bottle. Later still, with the help of artist Urs Fischer, this impromptu piece of artwork created in 1965 was reproduced (500 copies) and given by Joannou as “reverse gifts” to his friends and business partners on his 75th birthday in 2014. In the introduction to DESTE 33 Years Joannou writes: “For some, art is, above all, a luxury. But not for me. We don’t need it to survive, but we do need it. It has something to do with the soul. It is what man needs to make him more human.”

*Alexander Iolas (1907-1987) was an internationally recognised Greek gallery owner and art collector. He represented a number of well-known artists, including Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Jean Tinguely, Yves Klein and others. In 1983, a former employee accused Iolas of antiquities smuggling and the prostitution of young men, thereby causing a large scandal.

“Monument to Now” (2004). Installation view with Paul McCarthy, Pig, 2003; Maurizio Cattelan, Frank & Jamie, 2002. Photo: Courtesy of DESTE Foundation

- The Equilibrists at Benaki museum, Athens until 9 October; www.deste.gr

- Robert Cuoghi's Putiferio at DESTE Project Space Slaugterhouse, Hydra island until 30 October; www.deste.gr