Sometimes walls can say more than the audience expects them to

Estere Kajema

16/01/2017

Murals, arguably, could be considered the most ancient form of art. The first cave paintings were murals, even though their intention was not to be decorative or to serve as entertainment; instead, they were intended to be, literally, instructions for the painters’ descendants. If you think about it, a wall is the most easily approachable surface. It can perfectly accommodate any height; it is immobile and therefore is a perfect surface for information or image inscription. These sorts of ancient murals can be found in caves dating back to the Stone Age, on the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs, and later, as fresco-secco paintings from the Middle Ages. As time went by, the idea of a “mural artwork” expanded and began to include any work that was directly connected to the architecture. To go deep into the different methods and techniques of mural paintings is to write an academic art-history essay, which is not the purpose of this piece. In this essay I will discuss the ways in which it is possible for postmodern and contemporary mural art to intervene with the spaces that it occupies.

When talking about art on walls, one naturally thinks of two postmodern art giants, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. These two artists made the decision to use the surface of walls in order to express and explain the injustices and prejudices that they were surrounded with.

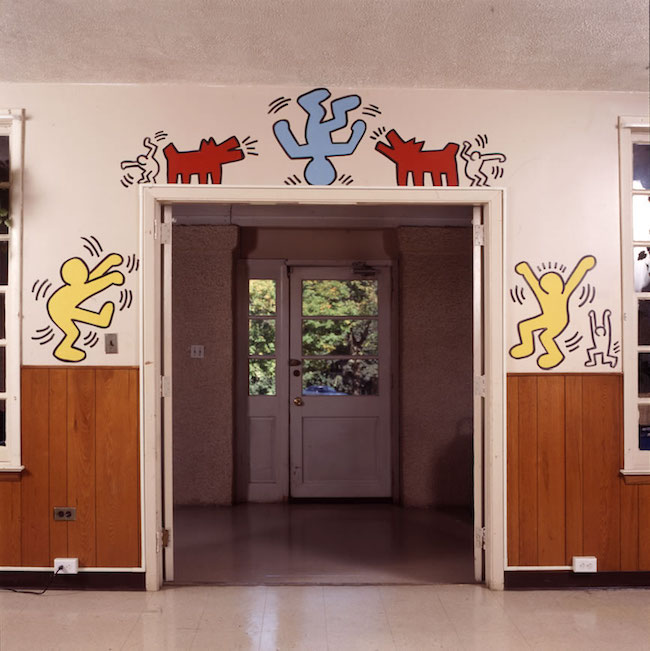

Keith Haring. Installation Shot. Shafrazi Gallery, New York, 1982

Haring, who was born in Pennsylvania, moved to New York City in 1978 to study at the legendary School of Visual Arts (SVA). In the big city, the artist was surrounded by young creators – other artists, musicians, DJ’s, designers. He was particularly excited by the graffiti culture that he discovered there. Working very hard at the School, Haring started to hang his artworks around the hallways for everyone to see – he had an unstoppable urge to have his work exposed.

“One day, riding the subway, I saw this empty black panel where an advertisement was supposed to go. I immediately realized that this was the perfect place to draw. I went back above ground to a card shop and bought a box of white chalk, went back down and did a drawing on it. It was perfect–soft black paper; chalk drew on it really easily.”[1]

Keith Haring, at Children’s Village

It was his Subway Period that made Haring a truly famous artist. These wall paintings connected the artist to the hip-hop and rap cultures – since this is where the New York City graffiti scene originated – but Haring’s drawings usually spoke of problems and questions that were different from that culture. Arriving in New York and coming out as a gay man was a crucial point in his artistic and personal life. A large part of the work that he did had to do with sex education – in particular, informing his public about AIDS. Haring once said that homosexuality had been made synonymous with death, and it was crucial for him to break this unfair bond.

Haring was fascinated with walls. The artist would turn any show he participated in into a unique and independent space, including his one-man show at Shafrazi Gallery in 1982.

He was fascinated with public spaces and used his artistic power to transform them. In 1984, Haring created a mural for the infirmary at Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry, in New York. In 1989, he transformed a toilet in the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Centre in Manhattan; it is now known as the Keith Haring Room.

Keith Haring. DJ, 1983

He would draw comic-like figures that were dancing, fighting, crawling, having sexual intercourse, swimming, turning into dolphins. In one of Haring’s most famous drawings, the artist depicted a barking dog-like figure that was also a DJ.

There could be many reasons why Haring chose walls as a surface for his drawings and paintings, but one that is particularly interesting is that Haring would often place his little figures into spaces that were reserved for advertisements. He realized that the use of these spaces would make his spectators feel uncomfortable because they are used to relying on advertisements when making life choices – what to wear, which perfume to use, where to go. Possibly, what Haring was trying to do, and what he definitely achieved, was making the general public question their daily decisions and the issues that they were preoccupied with.

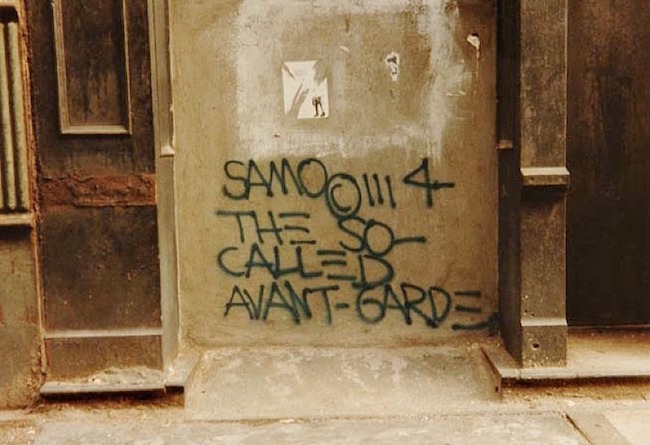

Jean-Michel Basquiat. “SAMO”, the so-called avant-garde

Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was previously mentioned, was Haring’s contemporary. He used walls to express a very different message, though. Basquiat was born in New York City, in Brooklyn. The artist had a very bad relationship with his father, who had become his sole guardian after Basquiat’s mother, Matilde, was committed to a mental institution. At the age of 15 Basquiat dropped out of high school, and his father kicked him out of the house. Basquiat started attending an alternative high school, City-As-School, which became a starting point for his career. At school Basquiat met Al Diaz, and together they started painting graffiti under the tag “SAMO”, written with a copyright symbol at the end. With help from their school friends, the two – Basquiat and Diaz – started tagging the walls, adding strange, uncommon phrases to their main SAMO motto, which meant The Same Old Shit. A famous art critic, and a man who was crucial to Basquiat’s career, Jeffrey Deitch, called the tags “disjointed street poetry”. The messages they were trying to express were rather obscure, for instance: “SAMO, the so-called avant-garde”.

In an interview with the Village Voice, Basquiat confessed:

“Teenage stuff. We’d just drink Ballantine Ale all the time and write stuff and throw bottles… just teenage stuff. […] It was supposed to be a logo, like Pepsi.”[2]

Even though Diaz always saw a deeper side of SAMO (for him, graffiti and the process of tagging had a much deeper philosophy attached to it), Basquiat always desired fame and glory. It’s quite possible that he used SAMO only as a means of gaining public attention. The evidence for this would be a famous anecdote – once, before he had even met Haring in person, Basquiat asked to be smuggled onto the SVA campus, where he then sprayed SAMO all over it. The artist knew where to leave his mark, and he did it very, very pragmatically. In 1980, Basquiat started writing “SAMO IS DEAD” on the streets of Lower Manhattan.

SAMO was dead, but Basquiat’s career was just beginning. The artist used the end of his collaboration and friendship with Diaz to promote himself even more. He used the surface of a wall to convince all of New York’s citizens and visitors that he was the King of the City; this statement was underlined by the second signature tag that Basquiat used – a crown.

Today, while such prominent artists as Banksy and Mr. Brainwash, who are only two names among hundreds of excellent street artists, are still using the exterior of buildings as a surface for their art, many contemporary artists are turning to interior walls – not only to prop up or hang their work from, but also directly using the surface. The following part of the essay will be a glance at the work of three artists – Lena Lapschina, Ai Weiwei, and Michael Craig-Martin, all of whom use the surface of a wall as a continuation and extension of their practice.

Lena Lapschina. View of the Arlberg mural, 2013

.jpg)

Lena Lapschina is a contemporary Siberian-born artist who has used the technique of drawing directly on a wall multiple times already. In 2013 she created the drawing titled “Sword, Dog, Mountain, Car”, which was commissioned by the Arlberg Hospiz Hotel in Austria. As the artist herself describes it on her website, the artwork is “… really huge: six walls, one hundred square meters, more than 600 meters of Pattex power tape.”[3]

Lena Lapschina. View of the London mural, 2016

.jpg)

Now, in 2016, Lapschina is working on another mural. This time the mural is located in a villa in Central London. Lapschina writes:“You are going to meet mountains, and people, and text, and even – in the salon – a giant.”[4]

By putting images directly onto the walls, Lapschina is almost letting her figures grow free – dogs, magical sword-fighters, gnomes, and even flowers, mountains and trees. These red forms surround and occupy the space, and by doing so they somehow become the hosts, the owners, the ghosts who are attached to the architecture. The characters, which one might be fortunate enough to meet in the stairway of one of these buildings, seem to be participating in some unearthly and transformative performance, completely and utterly revolutionizing the space they are in.

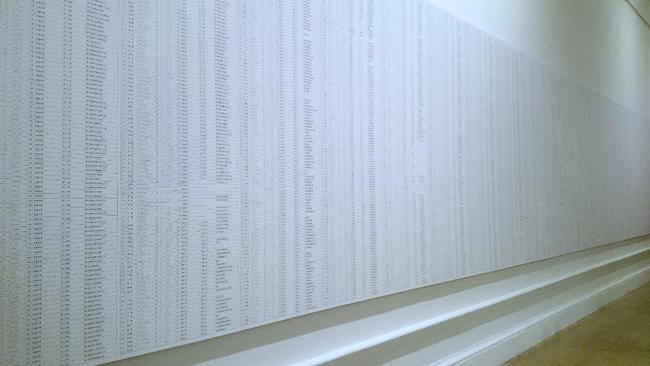

Ai Weiwei. Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens' Investigation, 2008–2011

Ai Weiwei. Straight, 2008–2012

Ai Weiwei’s method of using walls as a continuation of his practice is truly mesmerizing. He uses the surface in order to expand a work that can be seen inside the space that the walls surround. The two examples that shall be examined in this passage come from an exhibition that was on view at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2015.

“Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens' Investigation” (2008-11) is a work that was shown alongside Weiwei’s “Straight” (2008-12). Both works were created as an immediate response to the Sichuan earthquake of 2008; they showed the horribly poor engineering quality of the buildings in that area, particularly schools, which had been held together by the steel rods that Weiwei used in this installation. The buildings were not strong enough to withstand the force of the earthquake and they collapsed, leaving thousands of students dead. Weiwei collected the broken and twisted rods, and with the help of his assistants, he straightened them by hand, one by one. “Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens' Investigation” is a list of the students who became fatal victims of the earthquake. The list was gathered by the organization Citizens’ Investigation, which Weiwei founded to work against the covering up of the truth that was being done by the Chinese government. As the investigation went forward, several volunteers working for the organization were arrested. While preparing to testify for one of them in Chendu, Ai was brutally beaten up by the police, arrested, interrogated, and assigned one year of probation during which time he was not allowed to leave Beijing. The act of putting together this list of names – gathered with so much passion and courage – and then putting it up on a wall on such a big scale (and on the walls of one of the most important art institutions in the world, no less), is the most generous, brave and valiant deed that Weiwei could have ever done.

Ai Weiwei. S.A.C.R.E.D, 2012

.jpg)

Ai Weiwei. S.A.C.R.E.D, 2012

One of the final rooms of Weiwei’s RA exhibition became the temporary home for his work titled “S.A.C.R.E.D.” (2012). This complex work of art consisted of six large iron cubes, and seemed rather abstract upon first sight. When nearing the work, spectators were invited to stand up on a small stool and take a peek inside the cube – and to witness miniature scenes of Weiwei's imprisonment. The shocking accuracy and attention to detail of the horrible conditions that Weiwei lived in are truly terrifying.

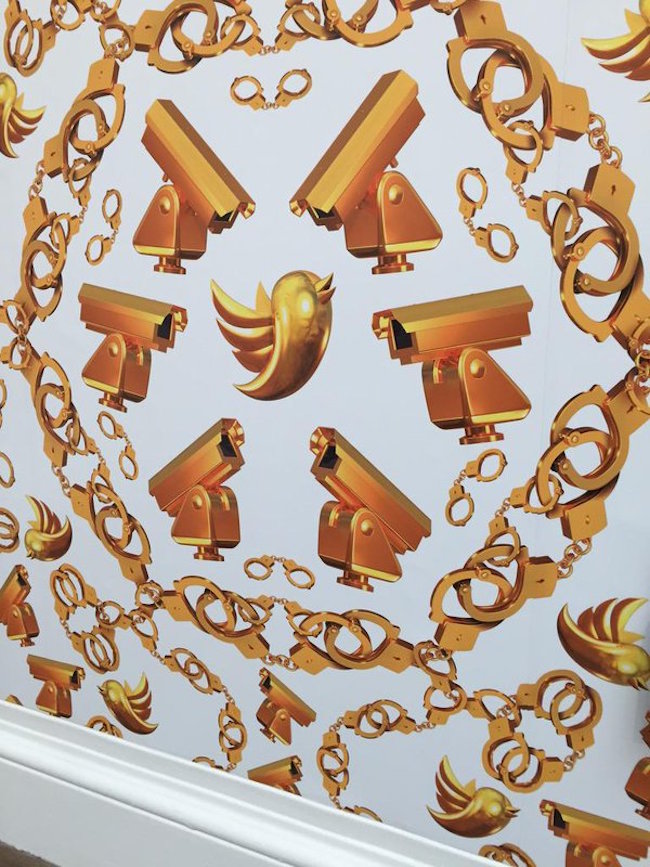

When looking above and around the six cubes, one’s attention was drawn to the walls of the space. Even from a distance, it is obvious that the wallpaper covering the walls depicts various shapes in gold – birds and chains. Upon coming closer, spectators saw that the walls were covered with the repeating image of the Twitter logo (a small bird) surrounded by six CCTV cameras and encircled with a chain of handcuffs.

Ai Weiwei. Wallpaper view at RA

The walls surrounding the "S.A.C.R.E.D." installation depicted an image criticizing the lack of freedom of speech in China – as we know, the Chinese government blocked Twitter in June 2009 under the state’s policy of Internet censorship.

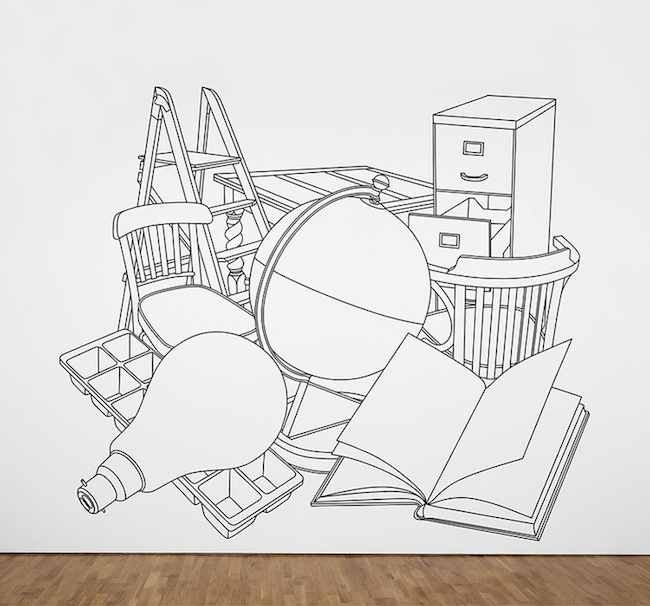

Michael Craig-Martin. Reading with Globe, 1980

Michael Craig-Martin is an Irish-British contemporary artist who often explores ordinary household objects in his work. In the late 70s, Craig-Martin started experimenting with the surfaces of walls by applying different materials directly onto them. He used tape, oil, metal, and neon tubes. In 1980 he created a wall installation made out of tape that had been applied directly onto the wall. The artist depicted objects such as a globe, an ice container, several chairs, a book, and a ladder – objects that one would find in an office or in a reading room.

Much later, during the “Transience” exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in 2015, Craig-Martin covered the walls that were supposed to be the background for his work with drawings of objects from everyday life – things that surround us today, specifically at the beginning of the 21st century: an iPhone, an Xbox console, headphones, easily recognizable McDonald's french fries. This wallpaper, which was created especially for the Serpentine exhibition, underlined the importance of a world made up of simple and recognizable items that surround us every day. To a degree of accuracy that is almost eerie, a spectator can easily identify an Apple mouse, a large iMac screen, and an Adidas sneaker. Julia Peyton-Jones, a former Director of the Serpentine Galleries, and Hans Ulrich-Obrist, a Co-Director, have said:

“Craig-Martin's acute observations present an extraordinary picture of recent developments in the production, processes, functions and form of the objects that populate our world. His work reveals a search for the ultimate expression of contemporaneity in a way that we all experience – through the items we use every day.”[5]

View of the “Transience” exhibition

Again, as with the work of Ai Weiwei, Craig-Martin’s decision to deepen and expand the subject that is already being explored in his paintings underlines the importance of the themes that he chooses.

It is important to understand the crucial difference between a painting or a drawing on a wall, and one done on a piece of paper, canvas, cardboard, or any other surface that can be dismounted or relocated. A message that is conveyed on a wall automatically achieves a different status, even if it happens on a subconscious level. A space that is antipodal to a white cube is a story; it becomes a home, a shelter. A wall that has been transformed by the artist him- or herself is a story and extension of his or her studio work. A voice from beyond, a hint that comes directly from the creator. A thing to remember is that sometimes, walls can tell more than the audience expects them to.

[1] David Sheff, “Keith Haring: An Intimate Conversation,” Rolling Stone, August 10, 1989, p. 63

[2] Faflick, Philip. “The SAMO Graffiti.. Boosh Wah or CIA?” Village Voice, December 11, 1978.

[3] “There is a mural on the very peaks of the mountains,” – artist’s website blog entry. lapschina.com

[4] “There is a giant in the City of Westminster”, artist’s website blog entry. lapschina.com

[5] Press Release for a Michael Craig-Martin “Transience” exhibition. www.serpentinegalleries.org