What is and isn’t correct?

Ilze Pole

22/02/2017

David Hockney

Tate Britain, London

9 February – 29 May, 2017

It was in London, spring of 2002, when Lucian Freud painted the portrait of David Hockney; for three months, for four hours a day, Hockney would pose in Freud’s studio – where, luckily, he was allowed to smoke and talk. Every morning, Hockney would head to Freud’s studio by going through the park, reverently taking in how spring was awaking it. He was so excited by this experience that he decided to address the phenomenon in his art, and to spend more and more time in his native Yorkshire painting landscapes. Which he later did, creating works that, next to his iconic paintings made in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 70s (“Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool” [1966]; “A Bigger Splash” [1967]; “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” [1972]), are celebrations of the beauty of nature in the manner of Matisse and late Fauvism.

David Hockney. Peter Getting Out of Nick's Pool, 1966. National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery. Presented by Sir John Moores 1968. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt

As Hockney’s 80th birthday approaches, this exhibition at Tate Britain is the largest retrospective of his work ever held. It features more than 140 of Hockney’s works, starting from his early works created while he was still a student at the Royal College of Art in the early 1960s, to the very latest ones, created just last year. The exhibition is spread throughout thirteen rooms, each one focusing on a specific aspect of his work and arranged chronologically. Hockney has often changed his style, experimenting with painting, photography and video, and even the newest technologies – the last room of the exhibition is devoted to his evocative iPad drawings – all done as part of his ongoing search for new ways to illustrate the world around us. Hockney himself has said that this retrospective has been a magnificent way to revisit works that he made decades ago, and to see how his works have developed over these years, resulting in him being just where he is right now.

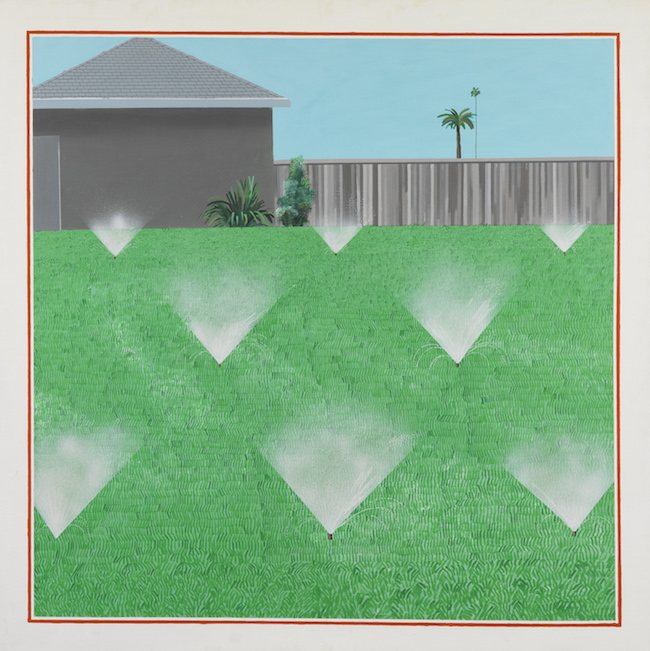

David Hockney. A Lawn Being Sprinkled, 1967. Lear Family Collection. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt

Hockney is regarded as the most popular and famous British artist of his time, although the popularity could be seen as a weakness of sorts – one that aided in covering up his instances of carelessness, bad style, and even mistakes. After the exhibition opened, the reviews in the British press weren’t exactly unanimously positive. Consequently, one of the tasks of the curators was to highlight the issues that Hockney had worked on throughout his life – what is the nature of pictures and picture making; Hockney had challenged all of the possible conventions, including the protocol of picture making and our assumptions of what is and isn’t correct. But most of all, he had challenged the notion of perspective. Hockney believes that we see the world from many dynamic viewpoints, and when one looks at his works from this aspect, they reveal themselves more deeply and compellingly.

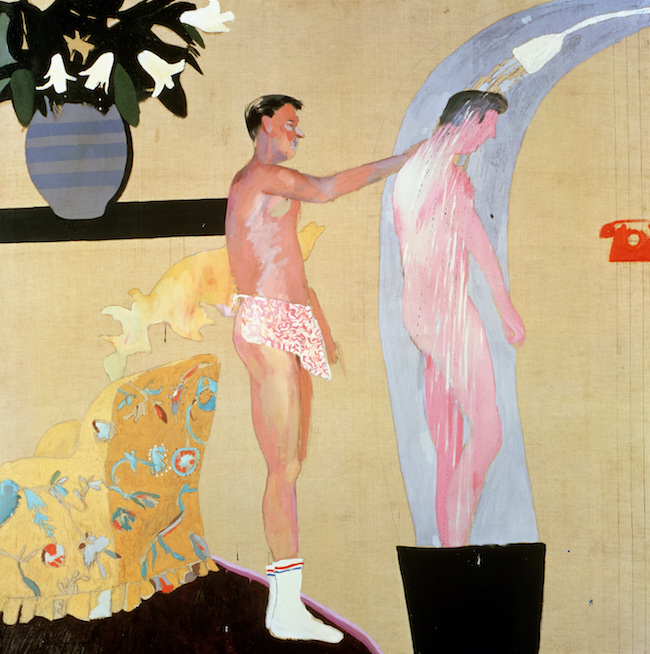

David Hockney. Domestic Scene, Los Angeles, 1963. Private collection. © David Hockney

During his studies in London, Hockney created “The Cha Cha Cha That Was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th of March”, “The Most Beautiful Boy in the World”, and “We Two Boys Together Clinging” (all in 1961). Hockney had abandoned a figurative style of painting and had instead embraced the informal abstraction; in terms of subjects, he took to heart what his friend, the American painter R.B. Kitaj, had told him (and what a whole generation of artists would adhere to): Why don’t you paint what you love? And, so, as David loved boys, he painted boys. At the time, this was considered radical and daring – he placed text into his paintings, coded references to his partners and his infatuation with others (including the singer Cliff Richard).

Hockney’s struggle with perspective, if one could call it that, is very visible in his 1963 work “Play Within a Play”; in it we see his art dealer John Kasmin, a very prominent figure in the 1960s London art scene and who, that same year, had opened a gallery on New Bond Street – a large space with white walls, something completely new at that time. “Play Within a Play” was based on the motifs of a Renaissance tapestry, as seen in its blue frame with gold tassels and royal lilies, as well as in terms of its perspective, which was one of the main innovations in Renaissance-era painting. Part of Hockney’s painting is covered in glass, against which Kasmin has pressed his face and hands. It’s as if he is sandwiched in between the glass and the painting, which itself looks like a stage curtain – a space that is precise from the aspect of perspective, yet judging by the way the chair has been painted next to him, physically impossible.

David Hockney. Model with Unfinished Self-Portrait, 1977. Private collection. c/o Eykyn Maclean. © David Hockney

Not long after, Hockney moved to the US; he lives in California to this very day, because the light there is like no other in the world. But back in the 1960s, on a London street, a travel agency was advertising tickets to the US for just 45 pounds; Hockney didn’t have the amount in full, but he had enough for a down-payment. “I had always thought that it cost thousands to go to America!”, he would later recount. Having received 100 pounds by way of winning a contest, and selling off a few paintings – some for 10 pounds, some for 15 – Hockney headed “across the pond”. And there he stayed. Hockney settled down in Los Angeles, quickly adapting to the environment and working jobs that we would now call iconic. In 1964 he lived in Santa Monica, not far from Los Angeles. He liked this city that was at the height of its construction: a wide-open urban landscape, office buildings sited according to precise geometry, lots of sunlight, blue skies and palm trees. Here in California Hockney met his partner, Peter Schlesinger, an art student who would become a model in several of Hockney’s works (“Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool”, 1966; “Room Tarzana”, 1967). At this time Hockney also created “A Bigger Splash” (1967), a painting with a precise, geometric script, clean lines, and a sudden and unexpected splash of water that shocks the peace of the composition by way of indicating the presence of a human. The splash is also a satire-filled gesture of Hockney’s, one that is aimed at abstract expressionism – so many painters had been splashing their paint onto the canvas, whereas Hockney had spent seven days painting the splash alone.

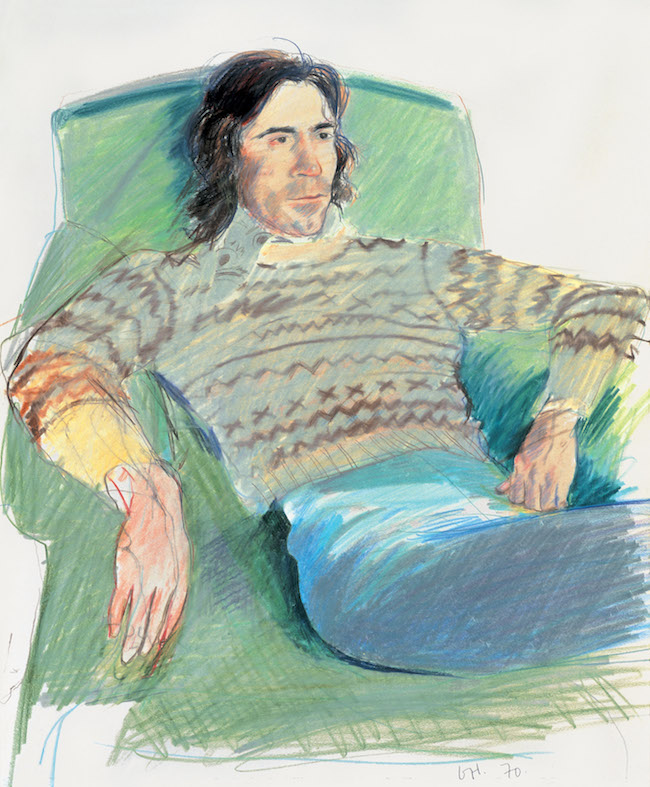

David Hockney. Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London. © David Hockney

David Hockney. Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, 1968. Private collection © David Hockney

Beginning with the late 60s, a different tone can be sensed in Hockney’s works. It is reflected in his series of double portraits featuring his friends: the environment becomes increasingly more intimate, and the paintings are dominated by the relationships they depict – between the people in the painting, as well as between the subjects and Hockney. Examples include “Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy” (1968), “American Collectors (Fred & Marcia Weisman)” (1968), “Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott” (1969), “Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy” (1970-1). Don Bachardy and Christopher Isherwood, the latter being the British author of the novel “A Single Man” (which was later adapted to film by Tom Ford, featuring Colin Firth in the lead), were friends of Hockney’s, and one of the first openly gay couples in Los Angeles; they often entertained authors, artists and actors at their home. Hockney has also repeatedly featured their house in his paintings, both its interior and exterior. Henry Geldzahler was an art critic and a curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, and up until his passing, was one of Hockney’s closest friends. Geldzahler didn’t distance himself from artists and preferred to move in their circles, ultimately almost becoming one of them.

David Hockney. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972. Lewis Collection. © David Hockney. Foto: Art Gallery of New South Wales / Jenni Carter

The next phase in Hockney’s career focused on experiments with photography, especially the Polaroid camera – using dozens (or even hundreds) of photographs, he would paint fascinating works. Here, too, he attempted to break accepted conventions, stating: “Photography is Ok...if you are a one-eyed Cyclops.” Since we are not Cyclopes, we see the world differently – we see it dynamically, we’re constantly changing our viewpoint. When Hockney grew tired of the white edges of Polaroid pictures, which impeded him in joining the images with one another, he turned to 35 mm film. One of his most interesting works from this period is “Pearblossom Hwy. 11-18th April 1986, #1” (1986), which is made up of more than 700 individually photographed frames. Each detail has been photographed from a frontal view – even the road signs, against which Hockney propped up a step ladder so that when photographing them, the perspective would remain frontal. The activity even drew the attention of the local police, who flew a helicopter above the scene to make sure that there weren’t any laws being broken. Related works are “Billy + Audrey Wilder Los Angeles April 1982” and “Walking in the Zen Garden at the Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto, Feb, 1983”. Hockney has said that back then, people would ask him if his works were even art, on which he later commented: “But I didn’t care whether it was or it wasn’t art, I made a lot of discoveries.”

David Hockney. Billy + Audrey Wilder Los Angeles April 1982. David Hockney Inc. (Los Angeles, USA). © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt

David Hockney. Hollywood Hills House, 1980. Walker Art Center collection, Minneapolis. Gift of Penny and Mike Winton, 1983. © David Hockney

In the 1980s, Hockney was asked to create stage sets for opera productions, including for the 1987 Los Angeles production of “Tristan und Isolde”. It was a huge challenge for him – for almost four minutes, only the orchestra plays, during which time the scenography must keep the audience focused upon the stage. However, set design wasn’t within Hockney’s comfort zone, and after a few more productions, he left the world of the stage. Perhaps it was too time-consuming of a job; perhaps the fact that he didn’t have complete control aggravated him. Hockney used to go to the opera often, and he especially liked to go with Henry Geldzahler. But those days are over. “I’ve almost completely lost my hearing; I’d have to sit in the front row, and even then it wouldn’t be easy,” he explains in a BBC documentary film. “Maybe that’s why I speak a lot, so that others don’t get the chance to talk. I wouldn’t be able to hear them.”

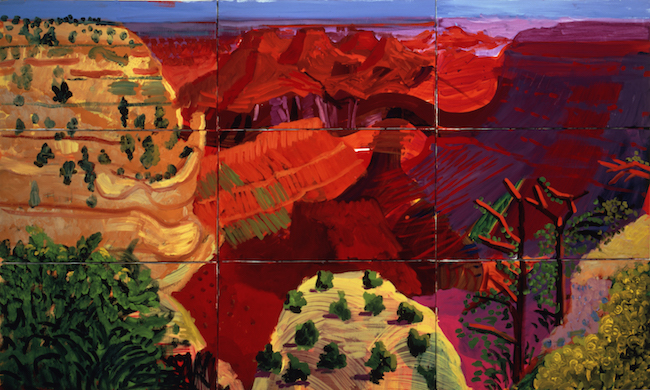

David Hockney. 9 Canvas Study of the Grand Canyon, 1998. Richard and Carolyn Dewey. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt

Hockney returned to painting. Landscapes increasingly appeared in his works, and an almost complete change in colors took place. He painted the winding road in the Hollywood Hills which he took from his home to his studio every day (“Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica”, 1990). The painting was created in a post-cubist space – a space of flatness, but nevertheless, also descriptive and realistic; it’s a place where the eye can wander, rather then be held up short. Hockney had also previously done “Large Interior, Los Angeles” (1988), in a similar manner. Another common subject for him was the Grand Canyon, which he has deemed “the despair of an artist”.

David Hockney. Going Up Garrowby Hill, 2000. Private collection, Topanga, California. © David Hockney

In mid-2000, Hockney returned to England, specifically to paint the Yorkshire landscapes. “The Road to Thwing” (2006) and “A Closer Winter Tunnel, February – March” (2006) revealed his next experimental step – creating works on several canvases, then combining them for a unifying effect.

One of the rooms at the Tate Britain has been given over to Hockney’s video installation of rural Yorkshire – “The Four seasons, Woldgate Woods (Spring 2011, Summer 2010, Autumn 2010, Winter 2010)”. In this video meditation, we see the same length of road, filmed during various seasons of the year, as Hockney slowly drove his Land Rover with nine cameras attached at different angles. One senses a great piety in this meditation of seasons, even a certain religiosity or spirituality in relation to nature and the artist himself as he attempts to capture it.

The last work Hockney made in Yorkshire, “Arrival of Spring (2013)”, is one of his masterpieces – a set of 25 charcoal drawings showing five different views/moments as spring unfolds. By using charcoal, he injects in these works a certain kind of melancholy, even if they depict the complete opposite – the arrival of spring and the celebration of life. There is a strong sense, perhaps, of his own mortality underlining these works. It was his final statement of Britain before he moved back to California that same summer. The eight years he spent in Yorkshire were very productive. In 2012, The Royal Academy of Arts in London organized the exhibition David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, which received more than 600,000 visitors. In addition to landscapes, at this time Hockney had also turned to more modern technologies – he took pictures with an iPhone and drew on an iPad, occasionally sending these drawings to friends. The iPad drawings can be seen in this exhibition as well, and not only that – visitors can watch how the drawings were made, with perhaps the most interesting thing being the ability to see exactly where Hockney began his work and how he developed it. Clever signatures accompany some of the works as well.

David Hockney. Garden, 2015. Collection of the artist. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt

Hockney’s departure from Britain was quite unexpected. Personal tragedies most likely impacted the decision – in September 2012 he suffered a stroke, and the following March, his assistant Dominic Elliott died at Hockney’s home in Birdlington, East Yorkshire, after drinking drain cleaner as a result of binging on ecstasy and cocaine. Hockney’s hearing deteriorated heavily after that. He left Britain...or perhaps, returned home…

Back in California, Hockney has continued to experiment with technologies, painting portraits and landscapes, including his garden and his house and swimming pool – “Pool Garden, Evening”, “Pool Garden, Morning”, both 2013. The newest work in the current exhibition is “Two Pots on the Terrace” (2016), done in shocking shades of blue and red. “I live the same way as I have for years; I’m just a worker. Artists are. Michelangelo, Picasso – they worked all the time. In the last four years of his life, van Gogh’s time is almost all accounted for. He did all those paintings, all those drawings, wrote all these letters. What other time was left over? Just enough for sleeping, that’s all. But you never hear about artists staying in bed, because they don’t.” [1]

The exhibition currently on view at Tate Britain was put together by Chris Stephens, Head of Displays and Lead Curator, Modern British Art; and Andrew Wilson, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art; with help from Assistant Curator Helen Little. It was organized in cooperation with the Centre Pompidou in Paris (where the exhibition will be held 21 June – 23 October), and the Metropolitan Museum in New York, to which the exhibition will travel after its Paris run.

[1] from “A Bigger Message”, Martin Gayford’s conversations with David Hockney