An uncomfortable green light

Olafur Eliasson’s and Ernesto Neto’s projects at the 57th Venice Biennale

30/05/2017

Two social art projects are featured as a part of Viva Arte Viva, the exhibition developed by this year's Venice Biennale curator, Christine Macel. Olafur Eliasson's Green Light – An Artistic Workshop, created in collaboration with the TBA21 exhibition space in Vienna and Francesca von Habsburg, and Um Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place) by Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto take centre stage at the Venice Giardini and the Arsenale. Even though in their present form both works of art were made especially for the Biennale, they focus on themes and issues that have been on the minds of these artists for quite some time. In the case of Green Light, the issues are migration, the refugee crisis and the integration of refugees. In the case of Neto's Sacred Place, it's the need today for a dialogue to take place between ancient wisdom and modern Western culture – after having met with shamans from the Huni Kuin tribe and undergone his own path of personal change, Neto believes such a dialogue is the only way humanity can survive the modern world. Similarly to Neto's previous projects at TBA21 in Vienna, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and KIASMA in Helsinki, he has again conjured a gigantic installation in Macel's “Shaman Pavilion” – a netted tent, or a space for meditative rituals and meetings that is called kupixawa in the Huni Kuin language. Members of the Huni Kuin tribe were also present at the opening of the exhibition at the biennale.

Significantly, and also paradoxically – especially in the context of the world in which we currently live – both Eliasson's Green Light and Neto's Sacred Place have become two of the most contradictorily reviewed art projects at the 57th Venice Biennale. And the exchange of these opinions is still in progress.

Olafur Eliasson. Green light - An artistic workshop. In collaboration with Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. Wood (European ash), recycled yogurt cups (PLA), used plastic bags, recycled nylon, LED (green). 35 x 35 x 35 cm. 57th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia VIVA ARTE VIVA. 2017. Photo: Damir Zizic. Courtesy of the artist and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. © Olafur Eliasson

To that end, a few quotes:

Cristina Ruiz writing for The Art Newspaper about the Green Light project: “Everything about putting refugees on display as exhibits in an art show feels wrong to me. Yes, they are consenting participants. But how many options do they really have? Are they in a position to turn Eliasson’s offer down? Why not organise a project with them off site instead of parading them in front of the public? Let people interested in the project seek it out. Let the others gawp at something else. This is not art in service of migrants but migrants in service of an artistic and curatorial vision.”

ArtNet about Neto's Um Sagrado Lugar installation: “It is meant to evoke the site of a sacred ayahuasca ceremony – though it mainly ends up as a funky chill-out zone for art tourists.”

The Economist: “These works, which emphasise collaboration and co-operation, are well intentioned, but the exhibition is so crowded that, instead of participating, most viewers just shuffle past, as if at a human zoo.”

Olafur Eliasson. Green light. 2016. In collaboration with Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. Photo: Sandro E. E. Zanzinger / TBA21, 2016. © Olafur Eliasson

An interdisciplinary experiment

As Eliasson said in an interview with The Art Newspaper, “I would love to say to Angela Merkel: ‘Here is a model.’”

The first Green Light workshop project was organised in 2106 at the TBA21 gallery in Vienna. Eliasson invited refugees and asylum seekers to participate in a symbolic process and make geometric “green light” lamps together with other people involved in the project (artists, producers, university students, teachers, sports trainers, psychologies, etc.). They thereby created a new object that served as a metaphor for cooperation and understanding. Not only for people who have been forced to flee their homes due to war or economic conditions, but also for the people living in countries that are now hosting refugees. The project centres on the issue of similarities and differences, about living together and people interacting with each other for the creation of a safer world. The lamp itself is simple – in fact, it's simpler than simple. It is made of recycled, environmentally-friendly materials and can be varied, just like human relationships. But there is another layer to the project that includes various seminars and language courses, with the goal of people exchanging information and becoming a platform where refugees are offered the chance to be heard.

Olafur Eliasson. Green light - An artistic workshop. In collaboration with Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. Wood (European ash), recycled yogurt cups (PLA), used plastic bags, recycled nylon, LED (green). 35 x 35 x 35 cm. 57th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia VIVA ARTE VIVA. 2017. Photo: Damir Zizic. Courtesy of the artist and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. © Olafur Eliasson

Thirty-five refugees took part in the project in Vienna organised by Eliasson and TBA21. They had all recently arrived in Austria on the latest wave of migration from Afghanistan, Syria, Nigeria, Tajikistan, Somalia and Iraq. All of those involved were volunteers, and the entire income generated by the project (the green lamps can be bought for EUR 250) was donated to support the “Green Light – Shared Learning” educational programme and several other non-governmental organisations working with migration issues. A second Greet Light project was realised early this year in Houston, Texas, with the Venice Biennale becoming the third site for the project. According to Eliasson, three more cities are currently discussing the possibility of hosting the project.

The Green Light workshop in Venice is located right at the heart of the Giardini's Central Pavilion, and in terms of energy it resembles a beehive. On the one hand, it is a work space in constant motion and process, where new lamps are being made by refugees, project participants and visitors. On the other hand, it is a place for conversations and the exchange of opinions, a place where a variety of discussions take place, a place where, for example, the Zalab documentary film studio from Italy is busy filming the refugees' stories. The project's activities are also shared on Instagram at @studioolafureliasson. Basically, it's a global, multinational space in miniature. Eliasson himself attended the opening of the project at the Venice Biennale, giving interviews and also participating in the workshop. Also present was art collector and philanthropist Francesca von Habsburg, Green Light's patroness.

When asked her view of the development of the project, Habsburg said, “One of the key elements of Green Light is the training programme, which we have called the 'sharing of knowledge'. I think the most important thing is for there to be interaction between people – between refugees and also between ourselves. We have invited artists, film directors, poets, authors, psychologists and people from a great variety of professions to take part in the workshops. As they work alongside each other, they talk about issues that are important to them, helping each other to cope with some very deep scars left by life. Not just on the part of refugees, but also for us, too. For example, understanding why we sometimes feel guilty for not dealing with this problem. We were, and still are, completely unprepared for this migration – but it's already become a global phenomenon, one that will only increase in the future, with ever more people finding themselves in a state of constant moving and relocation. The Green Light workshops are a learning process for everyone involved, learning about how to cope with this situation and social issues. It's not a solution, but it is a step towards finding a solution.

Olafur Eliasson. Green light. 2016. Wood (European ash), recycled yogurt cups (PLA), used plastic bags, recycled nylon, LED (green). 35 x 35 x 35 cm. Photo: María del Pilar García Ayensa / Studio Olafur Eliasson. 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. © Olafur Eliasson

“In working with the workshop at the Venice Biennale, we have involved local politicians, the city and the biennale itself. We must remember that just two years ago, at the previous Venice Biennale, the local authorities caused a scandal by closing down the mosque set up in the city centre by Swiss artist Christoph Büchel as a part of the Icelandic Pavilion. Today, there is even more pressure on the city to address current social issues.

“I think that the art world and the language of art, especially through the exhibition Christine Macel has created, is speaking about very fundamental issues. And that's what TBA21 has already been doing for many years. Dealing with political and social issues is at the core of the TBA21 foundation. That includes minority issues, which we've been working with already since 2006. (One of TBA21's first projects, which received much attention in the public sphere, was Küba, an ambitious video installation by Turkish artist Kutluğ Ataman that took two years to make. The artist filmed the illegal Kurdish district near the Istanbul airport and its inhabitants, thereby confronting Turks with minorities in their own land and also reflecting on the historical invasion of Europe by the Ottoman Turkish regime. The installation consisted of 40 television monitors on a barge that headed up the Danube River from the Black Sea to Vienna, with each stop along the way accenting a part of the ancient European trade route from Romania and Bulgaria through Serbia and Hungary to Slovakia and Austria. – Ed.)

“And now we're dealing a lot with the environment as well. As a collector, I do not collect art for art's sake. For me, it's important that this process has meaning, because it's not just about getting a new piece of artwork. It's a kind of journey in which the path to the key is a learning process. And of course, as a private collector, I can afford to experiment and take risks – I can try things out, knowing that I might also fail. Official institutions are usually afraid of failure. They have all these rules and regulations that keep them from really experimenting.

Olafur Eliasson. Green light - An artistic workshop. In collaboration with Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. Wood (European ash), recycled yogurt cups (PLA), used plastic bags, recycled nylon, LED (green). 35 x 35 x 35 cm. 57th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia VIVA ARTE VIVA. 2017. Photo: Damir Zizic. Courtesy of the artist and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. © Olafur Eliasson

“All of the refugees participating in this biennale project are from the Veneto region. In all, we talked with nine organisations that provide shelter for refugees. Most of them have been in Italy for six months to a year. They've come here from Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Kurdistan and Africa – Nigeria, Sierra Leone, The Gambia, Somalia, etc. There are a lot of Africans, and when we put them together, we realised that they're each from a different country. The thing is that they have all volunteered to come to this workshop. Today, for example, there are twelve, but it's different people every day, because it's quite stressful for them to interact with people. There are some fragile human beings here, and we do not want to objectify them with this project. We need to treat them with a tremendous amount of respect, take their feelings into consideration and protect them. Each of these people has a story, and all of them had full lives in the countries that they fled. There are doctors, teachers and university professors among them. We often automatically think about refugees as people who do not have an education. But actually, those who have wanted to participate in this project are usually quite sophisticated and well educated. Once you get them going, they're excited to be doing an art project. All of these lectures and meetings we're organising are not an end in itself or entertainment – the goal is to engage people. It's a two-way street.”

Eliasson himself calls Green Light a kind of interdisciplinary experiment. When asked whether he believes it's possible to change the world and society through projects like this and also Little Sun, he says, “It is a search for a new model. I think we're really looking at a collapse of the political sector. Not completely, but the EU is not responding with a very sophisticated strategy to the refugee crisis. We have an increase in illegal smugglers and the industry around refugees, so this means that we have to clearly reconsider things. I'm not saying I have a complete solution, but I think the culture sector is a lot stronger than we think with regard to coming up with new ideas. This why I like the idea of mixing the public sector, the private sector and the culture sector. To see if we can collaborate.”

Another question – do Green Light and similar projects have a strong enough voice? That is, are they capable of having any real influence? “I think the level of trust is higher because of it,” explains Eliasson. “As opposed to politicians and governments, which contain a lot of populism, trust in the culture sector is much higher. And also the potential that culture can offer.”

Olafur Eliasson. Green light - An artistic workshop. In collaboration with Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. Wood (European ash), recycled yogurt cups (PLA), used plastic bags, recycled nylon, LED (green). 35 x 35 x 35 cm. 57th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia VIVA ARTE VIVA. 2017. Photo: Damir Zizic. Courtesy of the artist and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. © Olafur Eliasson

In addition to the refugees from the Veneto region, who are encountering Green Light for the first time, the project also includes some of the very first refugees to have participated in the project and who have remained involved with it. For example, Tahajud Alghrabi, an Iraqi teacher who left her native country in 2003. “The Green Light project is like my family. I've travelled with it, and I feel it growing bigger. I think that the essence I feel when I work with people in the workshop is a message to people that we are all the same. Our team, Francesca, Olafur – we're all doing the same things. It's not like we're refugees and that's it. Each of us has different origins and a story of our own – education, work, all the human things. I'm with the project only because this is a place where I feel that there are no differences between us as people.”

Habsburg says that the future of the Green Light project is still open. “We can go anywhere in the world. I hope that some day Green Light might go to Sarajevo, too.” When asked about the response and support from other art collectors for the project, through their purchases of Green Light lamps, she laughs, “I'm putting on a lot of pressure...”

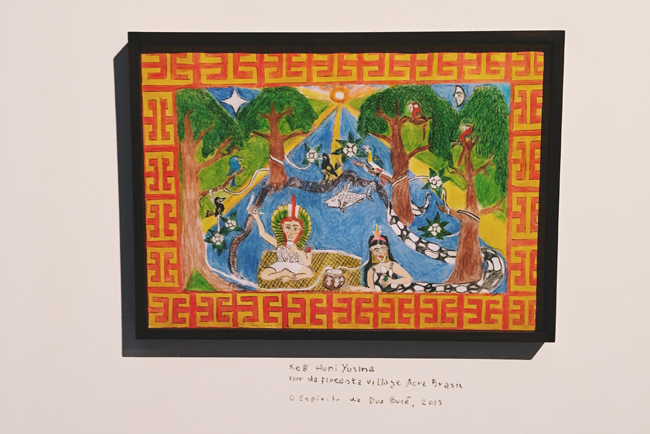

Ernesto Neto. Um Sagrado Lugar. “Encounter with the Huni Kuin” hosted by Ernesto Neto at the 57th International Art Exhibition.Venice, Arsenale, 13th May 2017

Art is a path

And still, what is it in these two (Eliasson's and Neto's) so expressly humanitarian and very topical projects that has elicited such passionate criticism brimming with negativity? The critics include venerable publications and respected art critics who berate the exhibiting of refugees (and native residents) as objects in an art show. They thereby continue to cultivate the division that still absurdly exists in our modern global world between Us and Them. At the same time, however, no one raises a panic, for example, about the exploitation of Doberman Pinschers in Anne Imhof's Faust in the German Pavilion, which won the main prize at this year's biennale. Or that people walking across a glass floor take countless videos and selfies with those (performers) walking around under the floor. As The Guardian wrote about Neto's pavilion: “(...) Inside sit actual members of the Brazilian rainforest tribe to which his installation is dedicated. This shocks somewhat – art as ethnographic zoo?”

Read in the Archive: An interview with Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto

That's why it seemed even more important for Arterritory.com to find out how the artists themselves react to these reproaches. Why, in their opinion, have the ideas behind Green Light and A Sacred Place been misunderstood or interpreted in a completely different way? In writing their harsh critiques, have the authors failed to immerse themselves in the ideological essence of the projects? Should we perhaps see it as an arrogance and superficiality characteristic of our time? Or is the Venice Biennale simply not the right platform to talk about these issues? In other words, what has historically been the world's largest and most prestigious art event has turned into a big social gathering with art as a backdrop – it is no longer a space where people truly wish to see in order to think, to hear in order to actually listen. And, if this is so, what would be the most effective way to use the language and power of art so that it can actually be heard? The answers we received from Eliasson and Neto follow and are published here in full.

Ernesto Neto. Um Sagrado Lugar. Photo:

Ernesto Neto:

“This negative criticism regarding our proposed sagrado lugar ['sacred place' in Spanish] is understandable. Art criticism and journalism are stuck on the mental level, as is most of humanity, whose mind is linked to power structures and material concepts. On our trajectory as Sapiens, we have fallen in love with this mental dimension – it is a part of our evolution as cosmic beings, but it's time to move on. What we are bringing [with this project] is a spiritual dimension, in which the indigenous people, in this case the Huni Kuin, are much more advanced than us. So, their presence generates attraction, but at the same time it also generates a kind of fear of the unknown, confusion and misunderstanding, if this last word makes sense.

Photo: Agnija Grigule

“The opening of the Venice Biennale is an avalanche of people who in a very short time need to see a lot of art and a lot of people, and in a way it very much represents this hungriness and consuming spirit that dominates our society today. So, the fact that the indigenous people's presence generates this strong negative reaction makes me think that the medicine is working on the spirit of the people, and maybe with time they will begin to ask themselves why they become so angry about their presence. On the other hand, there were also a lot of people who felt really connected through the experience and the presence of the Huni Kuin, which fills my heart with love and joy.

“To me, [Eliasson's] Green Light seems similar. It's this historically uncomfortable situation in which Europe lives, and the presence of refugees reproduces it. But they are just working, as there are a lot of people working at the biennale. For me it was interesting to encounter Olafur’s work methodology and also the presence of the force of Africa. Maybe a dance between these two forces can generate a lot of healing for the planet. Just like I believe can happen when there is contact between the Western force and the Huni Kuin and their indigenous spiritual knowledge. There is something bigger going on in the world right now than the quick reviews, and it needs time to grow.

Photo: Agnija Grigule

“Art institutions are the contemporary temples, and art is a bridge. At smaller places, as we have had in all our previous exhibitions with the Huni Kuin presence, we can have better contact and understanding than in a big group exhibition like the Venice Biennale. But Venice is the big encounter, the big contemporary salon where shocks occur when the vanguard appears, and this is very good!

“Art is still a path, and in the Western land of objectiveness, art is a subjective thread that can help us sew a spiritual social net. But this road is not mental. We can read about it and talk about it, but only experience can open portals. The spirituality of the Huni Kuin is one portal, but there are many others. All around us.

With love and joy,

Ernesto Neto”

Photo: Ģirts Muižnieks

Olafur Eliasson:

“It is true that bringing Green Light – An Artistic Workshop to the Exhibition Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale has provoked many reactions. Some have been positive, others sceptical, and some clearly negative. There have been a lot of questions in the workshop space itself and beyond it. Are people who came as refugees from very different countries – Nigeria, Ghana, Mali, Somalia, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, China – being objectified when they take part in a transnational workshop at the heart of the biennale? Can the visitors participate actively, rather than remain outside, gazing at the participants from a distance? What is clear to me is that the reactions to Green Light inevitably become a part of the project’s social fabric.

Read in the Archive: An interview with Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson

“The project explicitly invites the general public to join the participating asylum seekers in the workshop – it trusts the point of contact, encourages interaction and collaborative work. Being in the Green Light space and negotiating one’s role as spectator or participant is a part of the project, whether one comes from a refugee background or not. I think, however, that not everyone saw that invitation or was interested in seeing it.

“Bringing Green Light to the biennale means working under the scrutiny of the art world and within an exhibition platform that offers great visibility. It has been important to me throughout to actively use this visibility to bring the issues of migration and forced migration not just to those who are already interested in them (preaching to the choir, so to speak), but to everyone passing through the Exhibition Pavilion, since these are topics in the current political landscape that should not be ignored. It was also a means of giving the Green Light participants a platform from which they could speak about their concerns.

“Green Light – An Artistic Workshop presents no solution. It offers no easy ‘fix it all’ strategy. It is a modest attempt at addressing the issues surrounding forced migration and displacement through collaboration, community building and individual engagement.”

When, in relation to this discussion, I asked Belgian artist Jan Fabre (who is also present at the biennale, albeit as part of the satellite shows) whether he as an artist feels responsible to bring his opinions into current political and social processes, he responded (although adding that he had not yet seen Eliasson’s Green Light project): “Of course. For me it's unbelievable that in Europe – also in the Netherlands and in France – people have obviously forgotten that Adolf Hitler was elected in a democratic way. People sometimes have short memories. And of course, it's dangerous what is happening in Europe now, and we have to open our minds before it's too late. I think we [artists] have to support society in not going too much in that direction.”

Perhaps a red SOS beacon should be developed alongside the “green light”?