Art diary 2018

01/02/2018

Introduction

I’ve been writing a diary, I am proud of the process of writing for almost thirty-six years now; admittedly, I write in it sporadically, sometimes with breaks that are up to two years long. But breaks are not so important. What is the main thing is that it exists, always by my side, waiting until I get over my laziness and I finally pick up a pen and write something down. You read that correctly – a pen. My diary is handwritten; once one notebook is filled, I place it next to the others. From my collection, one can contemplate the whole history of writing paper manufactured in the Soviet Union, Russia, Europe – and now, China – beginning with the late seventies and up to the current day.

I write the diary for myself, and that’s why I use pen and paper. It is a twofold discipline of recording something (firstly ) and recording by hand in order to not lose the discipline of recording something by hand (secondly ). I don’t reread what I’ve written over these long years; who knows, I may never read it at all. That’s to say that the diaries will rot away after my death, having been read by no one. Actually, that is my intention. Of course, I don’t hide away my secret notebooks in a safe-deposit box ; anyone in the vicinity around me can quietly pick one up and read a few pages. I trust the moral decency of my friends and members of my family, but even if one of them does happen to fall into sin, they won’t find anything interesting in these notebooks. My youth diary , as one would expect, is full of anger at the world’s faults, imperfections, also you can find there a lot of dreams typical for this trouble age, , and so on. Later my diary consists of accounts of what I’ve read, heard, seen; going onwards, these are joined by New Year’s resolutions and remorse as friends and acquaintances begin to leave this life. Occasionally there is some mention of money or the weather. Not too long ago I noticed that personal “internal reviews” had begun to drop by the wayside; in fact, they have now completely disappeared.

These are the circumstances that spurred me to begin another diary in 2018. An electronic one, and not about me and my life but about the world. Although not like the diaries of the Goncourt brothers, Mikhail Kuzmin, or Lidiya Ginzburg. And not on paper, but on an iPad. There is no question regarding the second condition: I tote along this grand invention by Apple everywhere I go. I jot down all sorts of notes on things I observe. But then I got to wondering if I should perhaps arrange these notes chronologically. Why not? And now comes the subject, the question of what I am going to write about. . I’ve long mulled over the following simple thought: the world in which we live is not a theatre , as Shakespeare asserted, but rather an object of art – and an object of contemporary art, at that. If we add a bit of theology to the mix, then it’s also an object of conceptual art: we thought up the idea of a God who, like the ‘author-character’ of the Moscow conceptualists, directs a world which we he himself has created. There’s nothing blasphemous in my words: because if there is a God, then he’s playing a completely different game, right?

In conclusion, if Roland Barthes brought the semiotics of daily life into the limelight in his Mythologies, then I, being much more unassuming, simply think of everything that I see, hear, read or feel as being the phenomenon (forgive my pretentious style, but there is no other word for it) of contemporary art. This is not an indication of the good old ‘aestheticization of the world’, not at all. On the contrary – my aim is the de-aestheticization of art. In even simpler terms: I seek to transform life into a chronologically organised space or territory; moreover, a territory of art in which – let’s rephrase the famous phrase by Russian conservative icon Konstantin Pobedonostzev – wanders an inquisitive man. What follows are this wandering man’s notes on what he has seen and pondered.

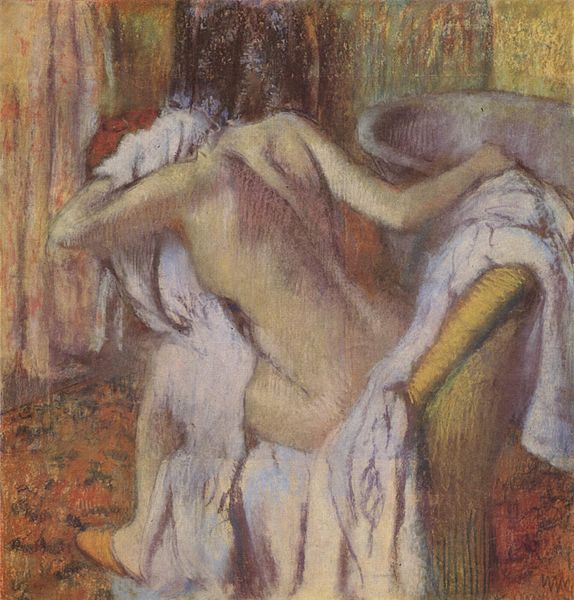

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas. After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself. About 1890-5. Photo: The National Gallery, London

December 31, 2017

On the last day of the year I finished up the last odds and ends, and am reading everything I hadn’t finished reading. Partly for the sake of mental housekeeping, partly because of boredom: I forbid myself from working on December 31. We used to drink ourselves silly on this day, but now…? Especially here in Chengdu – they have their own New Year in a month and a half, and today life goes on as usual, that is, for a Sunday. There’s sun, but you can’t go out for a walk; even the double-tongued Chinese weather app describes today’s air quality as being ‘Unhealthy’. This means that, in terms of human reality, curfew has set it, and one best not venture out of doors for quite a while. Which means that it is the perfect time to rewrite the birthdays of friends and family from the old daily planner to the new one (from an elegant grey-blue Italian one to a black and boring Chinese one), write in my diary, reply to unanswered letters hiding in the depths of gmail, and read articles I stashed away on Instapaper in 2017. And here we have Julian Barnes’ essay on Degas for the London Review of Books. Formally, it’s a review of three exhibitions and one book, all in one. In fact, it’s an essay of the kind that only Barnes can write – elegant, slightly wistful, Chekhovian (if Chekhov had been friends with the Goncourts, Zola, and Jules Renard, and had collected Manet, Renoir, or Degas). English essays written in a Chekhovian intonation and with French fineness, or something like that. However, it is first and foremost an English essay – logical, clear, and I had to look up only a couple of words (one of which the Oxford dictionary didn’t even have a listing for). So, it is about the Degas exhibitions at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, at the National Gallery in London (ongoing through May; I will definitely go once I return to Europe), and at the d’Orsay in Paris (this one closes on February 25, but then I’d have to make a special trip; my love for Degas is weaker than my laziness and stinginess – a truly Russian mix of traits, I must say). The book, for its part, is famous, and made quite a splash when it came out: Degas and His Model by Alice Michel. It was published ten years after Degas’ death, and everything about it is mysterious. First of all, we still don’t know who wrote it. Under the pseudonym of ‘Alice Michel’ hides someone who has written down the stories of Degas’ model Pauline. There were rumours that it was some novelist ‘Rachilde’, who also hid her true identity; she was a founder and editor of the Mercure de France, which published Pauline’s accounts of the artist. The book has now been translated into English (or ‘American English’, as Barnes states with innocent disdain). All of these events are taking place in commemoration of the one-hundredth anniversary of Degas’ death; he was lucky enough to head to the great beyond in the year of The Great October.

As one expects of Barnes, this truly is an essay: it seems he knows the Second Empire and the Third Republic better than anyone at the time or since, and he references numerous individuals, many of whom he adores. He begins with Jules Renard and continues with Lautrec, Renoir, Cézanne, Monet, George Moore, Whistler, Mallarmé, Zola, Maupassant, and even Puvis de Chavannes. The latter is mentioned in rather amusing circumstances. ‘Pauline’ (if such a person even existed; in any case, Degas had several models with that name) tells ‘Alice Michel’ that the old artist was crude, bad tempered and so on, although occasionally his tone would change and he’d turn soft and even nice . What can one say – a man in his later years, and one who was also losing his eyesight; does anyone become better with age? And yes, in his old age Degas became an anti-Semite. Nevertheless, whatever he was like, he never tried to coerce the model into becoming his lover; although Degas was a boor, he did have something of the gentleman in him. ‘There wasn’t any Weinstein stuff going on’ – Barnes writes in light parody of American English. As we know, Weinstein-like behaviour was rampant in the art world at that time. In describing Degas’ conduct, Barnes made me chuckle by referencing a contrasting incident (what should one do on December 31 if not have a laugh?): ‘Unlike, say, Puvis de Chavannes, who used to ask his models: “How'd you like to see a great man's cock?”’ Well, as an artist he ended up a nothing, but in his proclivities he was right where we are nowadays; except today he’d be either sending such questions on Twitter or annoying secretaries with his propositions. Admittedly, the sweet and painterly style of Chavannes is an ideal example of today’s intelligent notions of what is ‘Beauty’ – that is, it’s what you’ll get in answer if you ask people what they truly think and promise not to tell anyone; otherwise they’ll just give you platitudes on Andy Warhol or Rothko.

I am basically lying on a strange, sagging black sofa in a rented flat in a Chinese city in the middle of nowhere, it is December 31, and I am entertaining myself with the crème de la crème of English essayists’ thoughts on the crème de la crème of the European art world. It appears to be so straight out of old-fashioned aestheticism that I must ask myself if this is really happening. It’s much too much like a colonial novel written in the spirit of Graham Greene or someone else of that genre. Except for the fact that I have not travelled to a colony from a metropolis, but the other way round. Because here – in China, in Singapore and in other similar places – is where the future lies today; whereas in Europe lies the past. A past that is still relatively alive, but only on the level of how much money people from the kingdoms of the future will pay for it (either before or after – it doesn’t matter). This thought also entertains me.

But the most important thing is something else. Something very strange and exiting took place in France between (of course, approximately) the 1830s and the 1930s. Such a surprising concentration of great art and great literature has never existed anywhere else. Politically, these weren’t the best years in France: three revolutions, Napoleon III and his miserable demise, the unfortunate First World War. But if one looks at the most interesting aspect, the most important one, this is the time of Delacroix to Duchamp, of Nerval and Baudelaire to Proust and Valéry. And between them, not dozens, but probably at least one hundred more names. It has all been tightly interwoven into a fabric – not even a cultural fabric but a fabric of life, it appears. In fact, these people have invented part of our visual and cultural way of thinking. Benjamin, by the way, felt this acutely, even though he restricted the period to just the Second Empire, from the 1850s to the 1860s. This was right of him; it would be impossible to fit all of it inside one’s head. Barnes understands this well, which is why he pulls out from this fabric only a few threads which he, nevertheless, intricately pinpoints with which other threads they intertwine.

Alright. But here there is emptiness, a black sofa, the ‘Unhealthy’ outdoors, and in the shops, a basic red wine costs almost twice what it does in London. In imitating a rich cultural life, I ordered from Amazon a collection of Barnes’ essays on artists, published in 2015. It will await me in London. It’s called Keeping an Eye Open. That’s a good slogan. Let’s keep our eyes open for all of 2018 and not see a thing.

Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva. Fireworks in Paris. 1925. Paper, coloured woodcut. 37.3 x 45.8. Tretyakov Gallery

January 1, 2018

Thank God, it’s begun. I believe this is the first time I’ve celebrated New Year Eve alone. I like it. What I liked even more was that there were no fireworks, at least not in the part of Chengdu where I live. Of course, there will be loads of that for the Chinese New Year, but I’ll be gone by then. I don’t know why, but fireworks and rockets infuriate me. What are these people trying to prove or show by shooting into the sky? What are they aiming at? God? He’s been dead for a long time – although in another version he’s immortal and will never die. In the end it’s a pointless waste of ammunition. Or perhaps people are sending him, God, signals saying that we are here and we know how to be happy. But he’s already aware of that since he’s all-knowing. Or maybe they’re trying to illuminate the sky in such a silly and confusing way in order to see if, by any chance, there’s anyone there? But this would also be done in vain; as we know, Gagarin flew up there and didn’t find out anyone. There’s just one option left: by way of the fireworks they’re projecting upwards the things that they dream about, desperately dream about, while they stay down below. Or, they’re projecting what they imagine life in the heavens to be. In that case, it’s a form of primitive cave art: technically much more complex, of course, but for all intents and purposes it’s the same. That is, shooting up into the sky is, essentially, a primitive yet complex-in-terms-of-execution art form. In that case, there’s the question of ‘why?’. The world is already full of art: old and new, whatever kind you wish. Obviously this is not enough – especially for those who rarely or never go to art museums. Shooting up into the sky is truly a popular art, I suppose.

Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski). Thérese Dreaming. 1938 © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In December 2017 an online petition to remove the painting from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art collected more than 10,000 signatures.

***

Although I didn’t party hard, it’s accepted that one can loaf about on January 1. I tried to and was successful for a few hours. I didn’t feel enough sophisticated for reading, I had listened to enough music on New Year’s Eve, and so I decided to dig around Youtube and watch something not too long, something ‘artsy’. I happened upon a documentary on Balthus, made thirty years ago, if not earlier. As usual – especially if the subject is controversial from a philistine viewpoint – the film is full of silences, confusing parts, and pompous banality. Even though he’s more than eighty years old, Balthus is still handsome, has a fierce gaze, and is arrogant – he’s part Polish and part aristocrat, after all. He smokes with immaculate pretentiousness. Yet behind it all hides a surprising salaciousness, deep and quiet scandalousness, and, of course, confident amorality in the spirit of Bataille and his ilk (including Balthus’ brother, Pierre Klossowski). A young girl about fifteen years old, a model, comes to see the old sinner; she is similar to all of the girls he has put in his paintings since the 1930s. One gets the impression that Balthus has created a special centre for doing his selection centre . And then comes the amusing part (of the kind always found in these silly films about modernist and avant-garde artists; of course, other types of artists are filmed differently) – the main protagonist exclaims that all interpretations of art are bad, unnecessary, distract from the main thing, and the only important thing are what he feels and how he sees. Then he begins to rail against Freud and psychoanalysis, claiming that here is the main source of all sins. Literally a couple minutes later, the film shows other people, invited experts, interpreting Balthus’ works and tacking from the Freudian point of view. . See, that’s what the bad boys are like. On the whole, Balthus could never exist today: in New York they’re already howling, demanding that his works be removed from museum exhibits because it’s unethical and overwhelmingly a pedophile’s wet dream. I’d be willing to wager a good sum that in the next five years they’re going to go as far as Nabokov, too. I feel like Christ on the cross, in-between two robbers: on the right – idiotic holier-than-thous demand that everything alive be banned; on the left – idiotic protectors of Equality, Justice and Ideal Moral Purity demand the same thing but with different words. What will happen to everything I love: baroque cruelty, Orientalist kitsch, the libertine pedophobe Kharms...yes, basically everything from Shakespeare to Lucian Freud? They’ll stuff it away in some warehouse, leaving the boiled cabbage of morality with which to school the public.

Bjork on the cover of her album Utopia

***

After Balthus I decided to put on Bjork’s latest album, which I had purposely not listened to in the previous year. Everyone praised it, but I was certain that it was simply monotone droning with good intentions. Which is why I promised myself I wouldn’t listen to it. But I couldn’t help myself after having read the following in a music magazine: ‘Perhaps the world doesn’t need Bjork’s Utopia right now, but it’s the only thing that music needs right now.’ How can I resist something like that? Well, of course, it was right of me to avoid it. I’ve never especially liked Bjork, but over the past few years she’d begun to really grate: some sort of fairy-esque, romantic gynecology. Yes, it was pretty clear what it would be like. But see, here’s something that’s interesting: the transformation of smart pop music into sound painting; instead of songs – sound landscapes. This all started long ago, of course, in the 1970s, but now it’s almost mainstream in indy rock and indy pop. In 2017, albums like those of The National and, in some sense, King Krule (these two were at hand): the former is very good, the latter is not bad...in any case, it’s better than Bjork. That is, if it’s not hiphop and R&B, and not white stage-pop for rednecks (e.g. Taylor Swift), then it’s going to be something like this. I sense a conscious cultural (socio-cultural) change at the focus of white middlebrow culture overall, and a rather cunning one: let ‘them’ sing and dance; we’ll secretly make a frame for them, draw in the background, and decorate it...we, the world, are all just one big hug that comes from the heart – yet in the end, we’ll smother you in our embrace. Because we are the enlightened creative middle-class; we’ve given you this opportunity to fool around; since we’re always imperceptibly here, if something unpleasant happens, we’ll turn off the lights. The bands of the label Ghost Box created gloominess from the sounds of the past that was obsessed with the future; now it’s supposedly been replaced by the pure present – even and gentle. The world is not eternal, but ECM sound is.

January 7, 2018

While sitting in an airport in a city whose existence I was ignorant of just three years ago, waiting for a flight to a city which name was absolutely obscure to me two months ago, what else is there to do? Observe, and occupy myself with trifling mind games. The hardest is behind me: I fought my way through, from the university campus to the airport, crossing all of Chengdu in a slight panic – is the taxi driver going the right way? Will he understand the pinyin phonetics of this white devil? Then two security searches, although admittedly humane ones – more polite than the ones in Europe and America, without any intentional sadism. But in-between the taxi and the security check lay the unknown: at the check-in counter I say that if I’m only transferring in Xiamen, with Manila as my destination, can I check in for both flights at once? A complete blank, of course – ‘lost in translation’. OK, I’ll just have to face it later, in Xiamen; for now, I’ll relax and look around.

If an airport is big and at least somewhat international, it’s a calming place – like everything globalistic in this world. The dreamy ease of getting from one place to another, perfect models (perfectly dressed) decorate the display windows of perfectly pointless shops...glass, sheet metal, a sort of Crystal Palace of our time. The original was de-welded and removed from Hyde Park, and then it burned down in its new location; but it was precisely this structure and no other that spread its quickly cobbled-together great-granddaughters throughout the earth. The traveller has nothing to worry about, everything seems to take place automatically. Bad coffee at twice the price in one hand, your bag in the other; your gaze slides from Gucci to Duffy; lavatories are positioned every hundred metres or so – and clean ones, at that. Good hygiene governs here; the only rule-breakers are sweaty backpackers filling up their gap year (a romantic expectation of youth) with boring traipsing around the world. In truth they skulk about in the corners, and are usually sleeping. But otherwise it’s bliss; much like in a contemporary art museum or a good art museum.

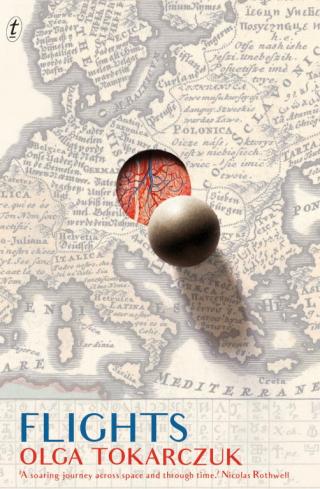

It was, after all, clear that I’d be giving myself over to this kind of reflection since I had recently read Olga Tokarczuk’s book, the Russian title of which has been badly translated as The Runners. The poor thing is probably still sitting in the Sports section, gathering dust (if they haven’t already tossed it). That’s too bad; it’s a great piece, even translated. I read it in English, in which the title has been superbly translated as Flights, thereby encompassing the notions of ‘refugees’, ‘runners’, and ‘flights’. Waiting for my upcoming ‘flight’, it’s nice to think about Flights. The wandering Tokarczuk writes that her true home is the airport; but it’s not only her home, it’s also a church and even a university (sometimes airport authorities enlighten passengers with pop-up lectures). For my part, I’ll add that the airport is an ideal contemporary art space. The high design of boutique adverts contain photorealism, hyperrealism, and pop art with surrealism; dozens of airport information displays, lines of text trickling downward like in ancient Chinese calligraphy, TV monitors showing the National Geographic and Discovery documentaries which look like the National Geographic and Discovery documentaries exactly, the news followed by amateur blooper videos, and large-scale catastrophes and private-sized catastrophes that are just as unreal in their pseudo realism. And, of course, performances: security searches, figures standing transfixed at the runway-viewing windows, a holiday traveller running with a full mouth as we hear the loudspeaker anxiously announcing: ‘Mr. Smith, Mr. Chen, the gates are about to close, please hurry’. And the main thing – don’t zone out while having a Heineken, and don’t freeze up while looking at a Kenzo jacket – you are not involved. You almost automatically do everything as you should, full stop; just like in contemporary art places. You are polite, quiet, indistinguishable. Everything around you has been thought out...look closely, unobserved by the world...have fun, everything is included in the ticket price. Just make sure you don’t poke away at your smartphone; remember your conscience. For what else is the voice of conscience if not the sense of satiety, which, accordingly, is the sensing of The Beautiful?

If I were an artist, I’d go see an oligarch and ask for the money to do the following art project: in some big airport, build a free-standing glass gallery that spans the length of the airport and connects the two furthest terminals. It could even be a glass tube. Sell tickets to visitors, hang up little signs describing things, like, ‘This object reveals the acute social problem of unemployment’, or ‘This one is about neo-colonialism’, ‘This one is on globalization’, ‘This one is on the loneliness and social despair of today’s men and women’, but this one here, see, is ‘A tribute to Velázquez’s Las Meninas within an advert for the wonderful children’s clothing store Alice in Pink Chains’. Moreover, instead of walking through this kind of a glass tube, one could crawl. The fun will never stop. It’s even more impressive than wrapping up the Reichstag.

Looking at it from the outside – that is, for passengers and airport staff – wouldn’t be bad either. The people crawling through the glass tube look around, talk about things amongst themselves with serious faces as they go (crawl!) along, take pictures, and so on. You could even raise ticket prices. Since you’d have to ask for money from Lufthansa, that’s just the way it goes.

***

(On the plane to Manila, having successfully transferred planes in the enigmatic Xiamen) Taking on the last of 2017’s articles filed away for later reading...and it’s silly. Peter Schjeldahl, who used to write about Balthus, is now flagellating himself in the New Yorker, saying yes, he used to admire a cynic, a Lolitophile, an anti-Semite, but the big thing now is the political art by Käthe Kollwitz and Sue Coe (this is supposedly a review of their show in New York’s Galerie St. Etienne)! The stupidest thing in the world is to praise someone using the shortcomings of another. To top it all off, Schjeldahl breaks the bad news: Balthus wasn’t a descendant of Polish nobility. There’s nothing perfect in the world.

I’m waiting next for a stern moral reproaching of Nabokov, shouted from the ideal ethical platforms of Maxim Gorky and Billy Bragg.

Photo: tatuirovanie.ru

January 11, 2018

For two days now I’ve been studying the tattoos on naked (almost naked) bodies on the beach. It looks like the fashion for letters, phrases and quotes has petered out. Hieroglyphs on white hands and backs have also become fewer. Letters are losing, even here; pictures are where it’s at: dense illustrations, often coloured, pop surrealism. Freaks, dragons, noodles of lines from which bearded snouts emerge. I remember with nostalgia the naive КЛЕН (I will love her forever) and СЛОН (death to cops by knife) criminal tattoos from my proletarian Soviet childhood. By knife! Now those were the days. But now it’s no longer a simple tattoo but rather science fiction, a dystopian catastrophe film. Post-apocalyptic fantasy violence (having been thrown out of the allowed public discourse) and the attack of the new barbarians have now taken over the human body. Should I write an essay titled ‘The Zeitgeist, as Illustrated at the Beach’? Or maybe ‘The Beach Series: A Colouring Book’... Why, truly. I did see, by the way, one brilliant phrase tattooed on a young English working-class bloke (from Manchester, judging by the accent). Along the bottom inner edge of his right foot, in two colours: ‘Forever Punky’.

Steven Slaughter. Portrait of Sir Hans Sloane. Canvas, oil. 1736. National Portrait Gallery, London

***

The Saatchi Gallery has been at Sloane Square for five years now. In that spot there used to be a completely different house, that of the truly great art collector Hans Sloane. The square has been named in his honour. Saatchi… so, what about Saatchi – I don’t remember who came up with the barb about millionaires who go crazy for art: ‘like a rich person walking into a department store’. OK, in Saatchi’s case, he built this department store himself and selected the wares, even hired specialists to put everything in its place. Sloane was completely different. He died in 1753, leaving behind a library with 50,000 books, a collection of manuscripts, coins and medals (32,000 units), an antiquity collection (1000 units), 6000 sea shells, 5000 dried insects, 1000 stuffed birds, 300 herbarium volumes containing 120,000 specimens, as well as 12,000 boxes of dried seeds and fruits. There were about 2000 more objects that couldn’t be classified as anything else than ‘Miscelania’. Sloane lived for 93 years and just collected and collected. I imagine the life of this court physician who served three successive English sovereigns...an investor and enthusiast who, at eight in the evening, was always at home and drinking hot chocolate (there were rumours, unfounded ones, that he had invented the drink). Sloane amassed his collection himself, although he did use the services of agents, one of whom was some adventurer named George Psalmanazar. (Possible future pseudonym for me?) Sloane collected anything and everything; after his death it all became the foundation for the creation of the British Museum, the British Library, and the Museum of Natural History. Although, after two and a half centuries, many things have either disintegrated, rotted, or simply been thrown out.

For God knows what reason, I thought about Sloane today as I basked on Palawan Beach. Well, it wasn’t actually all that out of place. First of all, a biography of him was published last year (written by somebody named James Delbourgo) – thick and expensive; among my resolutions for 2018 is to throw my thrift to the wind and buy the book for myself as a birthday present. I have more than a few unread thick books lying about the house; their presence makes life bearable. And then I think, here I am, loafing about as the waves splash ashore, whereas Hans Sloane would be trudging through the sand in his heavy coat, tights and wig, collecting sea shells. How low we have fallen, how low. We know how to show our tattooed naked bodies to the sun, but that’s it. Perhaps all that will remain of us is Saatchi’s junk art collection (which will end up useful to no one, I’m quite sure). A New British Museum with a British Library won’t be founded upon anything we’ve left behind.

And then, of course, I remembered that it was Saatchi who thought up of the Young British Artists, which included Hirst. But what is Hirst without the taxidermy of the Natural History Museum? Without the skulls from the British Museum’s ethnographic departments? It seems Athos was right, ‘we are like dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants’.

A separate subject – the great art of the old drawers and engravers of birds, fish and flowers. Now that was real art, useful art. I shouldn’t forget to think about this some time later, later, later...after Palawan.

.jpg)

Engraving. Lee, H. 1887. The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary: a Curious Fable of the Cotton Plant, to Which Is Added a Sketch of the History of Cotton and the Cotton Trade. S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London