The world is blue

This summer numerous art institutions are honouring the 90th anniversary of the birth of French artist Yves Klein

01/08/2018

Yves Klein (1928–1962) was an extremely vivid, important and controversial, albeit brief, phenomenon in French art in the 1950s and 1960s. In the best traditions of the avant-garde, he searched for new forms of expression and new concepts for discovering the world. In spite of his tragically short life and autodidacticism, he is undoubtedly one of the most influential creative personalities of the second half of the 20th century: a painter, sculptor, composer, theoretician, mystic, judoka, visionary, experimenter, conceptualist, and innovator who laid the foundations for conceptualism, minimalism and performance art. The fact that Klein is still current more than half a century after his death can be confirmed by, for example, visiting the “News” section of the yvesklein.com website, which is full of exhibitions and events related, to a lesser or greater degree, to his work.

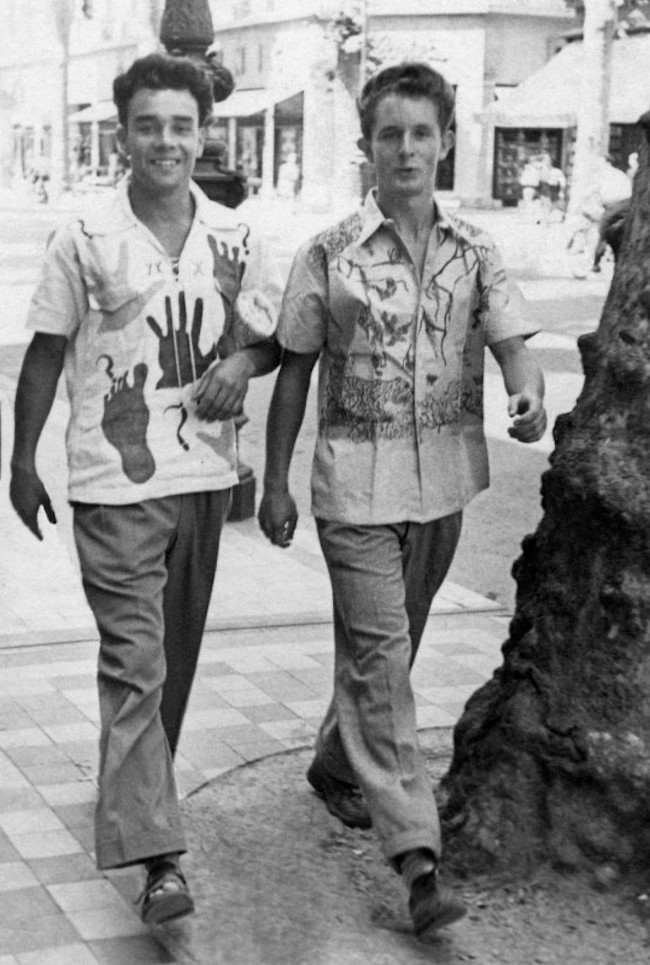

Installation view, Blenheim Palace. Yves Klein, Relief Portrait of Arman, Relief Portrait of Claude Pascal. Courtesy of Blenheim.

This year, in commemoration of what would have been his 90th birthday, art institutions have been particularly active in promoting Klein’s creative legacy. One of the largest of such events opened at Blenheim Palace (Woodstock, Oxfordshire, Great Britain) on July 18 and is on view until October 7. A collaborative project between the Blenheim Art Foundation and the Yves Klein Archives, the grand retrospective displays the artist’s most significant work – paintings as well as sculptures and large-format installations – in an 18th-century setting. Another exhibition, on show since June 1 at the Venet Foundation in Le Muy, France, shows off Klein’s work on an altogether different scale. There, the Pure Pigment installation covers the entire New Gallery space, its more than 200 square metres being painted in Klein’s characteristic blue pigment.

Visitors approach the installation through a minimalistic white space, a narrow concrete-and-glass corridor that opens onto a large, blue space. Although unable to step into or onto the blueness (Klein’s legendary hue, labelled IKB, or International Klein Blue), they nevertheless immerse, even lose, themselves in the colour’s vibration, which stretches to the horizon, so to say. The pigment is not mixed with any other, nor is it fixed in any way; it is completely pure, only “the colour itself”, as Klein put it.

Installation view. Yves Klein, Jonathan Swift (c.1960). Courtesy of Blenheim Art Foundation. Photo: Tom Lindboe

The installation at the Venet Foundation pays homage to Klein’s 1957 exhibition at the Colette Allendy Gallery, called Pigment pur (Pure Pigment). That was the first time viewers encountered a painting on a completely horizontal plane, giving them an absolutely new experience of space. “Pure pigment, exhibited on the ground, became a painting itself rather than a hung picture; the fixative medium being the most immaterial possible, in other words, the force of attraction itself. It did not alter the pigment grains, as oil, glue, or even my own special fixative inevitably do. The only drawback with this, one naturally stands upright and gazes toward the horizon,” wrote Klein in Notes on Certain Works Exhibited at the Colette Allendy Gallery. One must say, however, the installation at the Venet Foundation is the first time this work of art has been presented in such a dimension. It will be on show until September 15 by prior reservation.

Klein’s native city of Nice, for its part, is celebrating the artist with an innovative, interactive exhibition in an altogether atypical location, the Nicetoile Shopping Centre. Occupying 60 square metres on the first floor of the shopping centre, Yves Klein: The Interactive Exhibition...The Vibration of Colour (until September 30) combines art with new technologies. Namely, it has digitalised Klein’s most iconic works of art in 3D and ultra-high definition format, thus letting visitors become a part of the artist’s universe and experience a journey of vibrations into the space between materiality and the world of sensation. The exposition responds closely to visitors’ own movements, the digital and audio technologies helping them to become part of the artwork and virtually approach the intimacy of the creative process. For example, a movement of a hand becomes a “live paintbrush” in Klein’s famous Anthropometries series, and so on.

“I arrived on earth in 1928. Born into a milieu of painters, I acquired my taste for painting with my mother's milk,” Klein said. His mother, Marie Raymond, was a painter and the leading figure in the Art Informel movement. His father, Fred Klein, painted landscapes and figural compositions in the post-Impressionist style. Although the young Yves grew up in a creative environment, he did not receive formal training in art as a child. The Klein family lived in Paris but spent the summers with their artist friends in Cagnes-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, where Yves was often left in the care of his aunt, Rosa Raymond. It was thanks to her that Klein embraced a firm and pragmatic outlook on life, which was in sharp contrast to the carefree lifestyle of his parents.

From 1942 until 1946 Klein studied at the National School of the Merchant Navy and the National School of Oriental Languages. During this time, he became close friends with the young poet Claude Pascal and the young sculptor Armand Fernandez (Arman). They shared an interest in judo (a fashionable martial art at the time), jazz, esoteric literature and eastern religions. It was also at this time that Klein began painting, and already from the very beginning he strictly avoided using lines. “I am against the line and all its consequences: contours, forms, composition,” he stated. “To me, all paintings with lines, no matter whether figural or abstract, look like the barred window of a prison cell.”

Yves Klein and Claude Pascal in Nice, 1948.

“As I lay stretched upon the beach of Nice, I began to feel hatred for birds which flew back and forth across my blue, cloudless sky, because they tried to bore holes in my greatest and most beautiful work,” remembered Klein. The story of the three friends lying on the beach in Nice, dividing up the world amongst them, has already become the stuff of legend. Arman received the land, Pascal language and words, and Klein received the “emptiness”, or the ethereal space around the planet. “In 1946, when I was still an adolescent, I went and signed my name on the other side of the sky during a fantastic 'realistico-imaginary' voyage.” This symbolic gesture of signing the sky has been considered the young artist’s moment of revelation, which set the stage for all of his subsequent creative attempts to “catch the infinite and indefinable”.

This enlightening revelation led Klein to experiment with both painting and music. For example, in 1949 he composed the “Monotone Silence” Symphony, in which a full orchestra and choir hold a D major chord for 20 minutes, followed by 20 minutes of meditative silence. Klein explained that the composition embodied the acoustic pitch of a monochrome blue sky (“emptiness”) and strived for universal harmony.

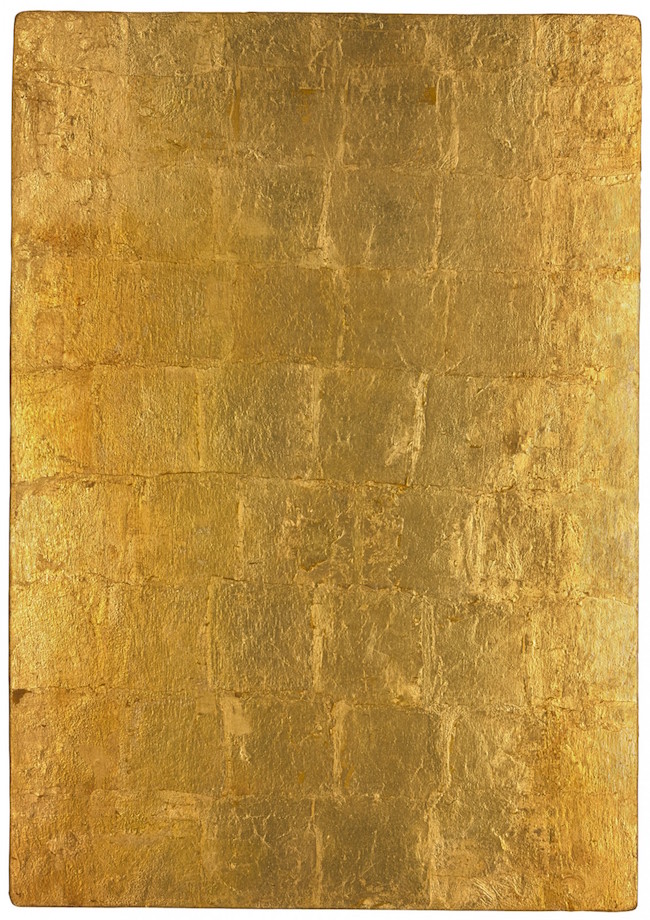

Untitled Monogold MG 24. 1961. Gold leaf on panel. 61 x 43 cm. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris.

“And then – gold! These sheets literally fly away at the slightest movement of the air; as they fly, they need to be caught with a knife in one hand and a gilding cushion in the other. The gold leaf is then carefully laid on a prepared surface that has been moistened with gelatine water. What a material! There is no better lesson in how to show respect towards a sculptural material!” From 1948 until 1952, Klein lived with Claude Pascal in London, where he worked as an assistant in Robert Savage’s framing shop, learning the basics of gilding and painting. He later put this fine craft to use in his Monogold series of gold paintings (1959–1962).

Untitled Green Monochrome M 35. 1957. Dry pigment, synthetic resin, gauze, panel. 61 x 40 cm. © The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris.

“It was in 1947 that the idea of a conscious monochrome vision came to me... Pure, existential space was regularly winking at me, each time in a more impressive manner, and this sensation of total freedom attracted me so powerfully that I painted some monochrome surfaces just to 'see', to 'see' with my own eyes what existential sensibility granted me. Absolute freedom! But each time I could neither imagine nor think of the possibility of considering this as a painting, a picture, until the day when I said: why not?”

In the late 1940s Klein actively began making monochrome paintings, and in his Monochrome Manifesto he announced that monochrome is an “open window to freedom, it is the possibility of diving into the immeasurable essence of colour”. His goal was to call up emotions and feelings independent of lines, depicted objects or abstract symbols, believing that a monochrome surface frees a painting from materiality. In 1956 he settled in Paris and caused a sensation with the exhibition Yves: Propositions monochromes at the Galerie Colette Allendy, bringing himself to the attention of the art scene in the French capital. The exhibition consisted of twenty monochrome paintings in blue, red, yellow and orange, but the public’s reaction disappointed Klein; critics and other visitors perceived it as the abstraction of a new form instead of an infinite journey into the immateriality of a surface. Only the young French critic Pierre Restany immediately saw the strength in Klein’s monochromism and extended positive remarks in support of the artist.

Reflecting on the public’s erroneous interpretation, Klein decided to go even further and focus on only one colour, his favourite – blue. “I was trying to show colour, but I realised that the public were prisoners of a preconceived point of view and that, confronted with all these surfaces of different colours, they reconstituted the elements of a decorative polychromy.”

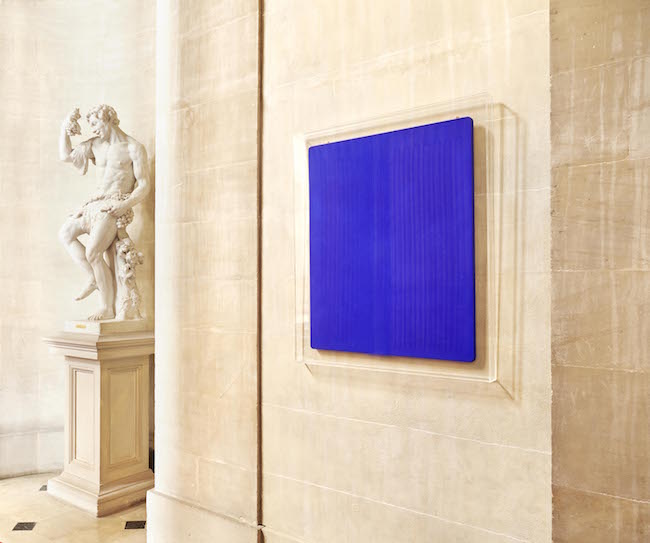

Installation view, Blenheim Palace. Yves Klein, Untitled Blue Monochrome. Courtesy of Blenheim Art Foundation. Photo: Tom Lindb

“It was then that I remembered the colour blue, the blue of the sky in Nice, which was at the origin of my career as monochromist. I started work towards the end of 1956, and in 1957 I had an exhibition in Milan which consisted entirely of what I dared to call my ‘Blue Period’. [..] Blue has no dimensions, it is beyond dimensions, whereas the other colours are not. [..] All colours arouse specific associative ideas, [..] while blue suggests at most the sea and sky, and they, after all, are in actual, visible nature what is most abstract.”

In 1956, with the help of Parisian art paint supplier Edouard Adam, Klein managed to dissolve his beloved ultramarine pigment in synthetic resin in such a way that, unlike oil paints, it maintained both the intensity of the colour and also partially its powder-like texture. Thus he created his very own colour, his mark of recognition: International Klein Blue, or IKB. This colour became a symbol of his creative output, a key on the path to the “infinite” and “lofty”. He made use of IKB in many of his paintings, sculptures and installations, and he used this same code to name his paintings, namely, IKB + the serial number. In 1957 at the Galleria Apollinaire in Milan, Klein exhibited eleven brilliant, identical IKB paintings, which were hung from posts 20 centimetres from the wall. The exhibition met with the approval of critics, was a commercial success and travelled to several other European cities as well.

Entrance to the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris during the opening of Yves Klein’s Le Vide exhibition, 1958.

Klein developed his concept of the immaterial even further in 1958, when he organised an exhibition titled Le Vide (The Void) at the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris. Everything was removed from the gallery space except for a large display case, and the walls were painted white. Klein believed that through the emptying of the gallery “the invisible will become effectual through the perceptible”. He created a complex entry ritual for the evening of the exhibition, and, thanks to the good publicity surrounding the event, approximately 3000 people stood in line to enter the completely empty gallery.

View of Yves Klein’s Le Vide exhibition at the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris, 1958.

“I remain detached and distant, but it is under my eyes and my orders that the work of art must create itself. Then, when the creation starts, I stand there, present at the ceremony, immaculate, calm, relaxed, [..] ready to welcome the work of art that is coming into existence in the tangible world.”

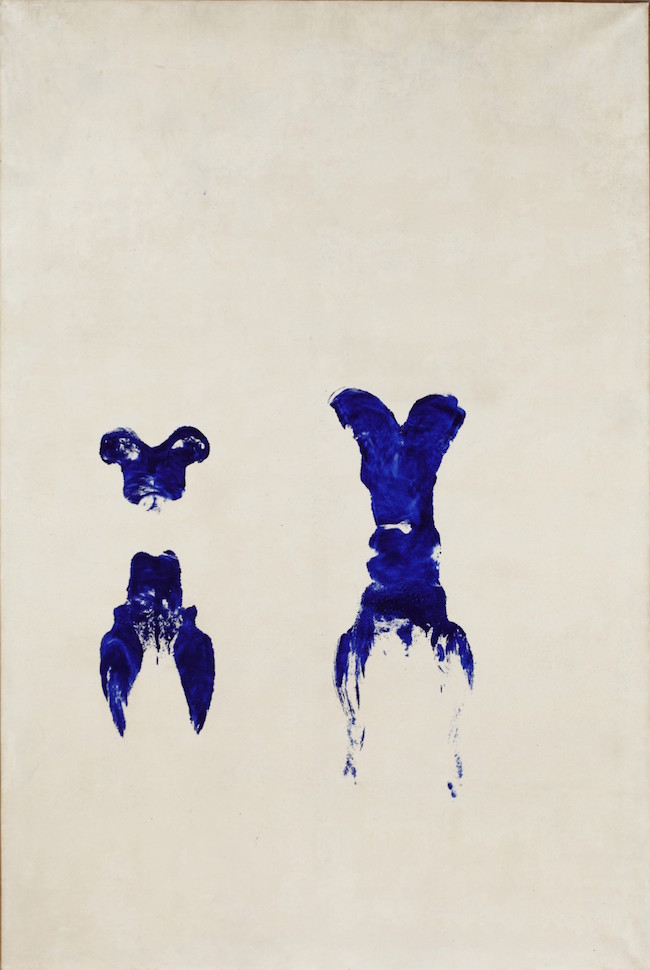

Around 1960 Klein moved away from direct contact with the canvas and experimented with various methods of applying paint: rolls, sponges, etc. This resulted in his most famous and provocative series, titled Anthropometries, in which IKB was applied using live models. The first pieces in this series were exhibited in a kind of exhibition-performance at the International Gallery of Contemporary Art in Paris, in which nude models covered themselves in IKB paint and rolled around along the walls of the gallery, leaving behind blue imprints of their bodies.

Yves Klein’s performance “Anthropometries of the Blue Period” at the Galerie Internationale d'art contemporain in Paris, 1960. © Photo: Agence Dalmas

Untitled Anthropometry ANT 67. 1960. Dry pigment, synthetic resin, paper. 223.5 x 150 cm.

At the same time, Klein became more and more enamoured of natural elements, introducing fire, water, sponges and gravel in his paintings and sculptures. “I dash out to the banks of the river [..] amongst the rushes and the reeds. I grind some pigment over all this, and the wind makes their slender stalks bend and appliqués them with precision and delicacy onto my canvas [..]. I obtain a vegetal mark. Then it starts to rain; a fine spring rain. I expose my canvas to the rain...and now I have the mark of the rain! A mark of an atmospheric event.”

One of Klein’s best-known uses of the elements in his artwork are the so-called fire paintings, created using a special method involving gas flames.

Yves Klein creates Fire Painting F 71. “Gaz de France” Test Centre, Saint-Denis, France. © Photo: Louis Frédéric.

Untitled Fire Painting F 64. 1962. Burnt cardboard on panel. 43 x 35.5 cm. © The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris.

On January 21, 1962, dressed as a knight of the Order of Saint Sebastian, Klein married the artist Rotraut Uecker. In May of that same year he suffered the first of three heart attacks. He died on June 6, 1962, at the age of 34. Shortly before his death, he had told a friend, “I will go to the biggest studio in the world and make only immaterial works.”

Yves Klein. La Vibration de la Couleur at the Nicetoile Shopping centre in Nice. Installation fragment. © Arterritory

Yves Klein is best remembered for his use of a single colour, the deep ultramarine hue known as IKB, which became his very own personal brand. Some critics see Klein as the direct descendant of Marcel Duchamp – a jokester who mocked all of the accepted norms of painting and opened the door to new media in art. Others see him as a follower of the early avant-garde – Kazimir Malevich and Alexander Rodchenko. Klein can likewise be compared to his peer Joseph Beuys – both were interested in romanticism and mysticism, and, like Beuys, many called him an obscurant and charlatan. It is, however, undeniable that Klein’s eccentric mix of mystical and materialistic views led many of his contemporaries, as well as artists of coming generations, to believe that an artist’s life can manifest itself in various different ways: writing, painting, performance, etc.

“The essence of painting is that something, that ‘ethereal glue’, that intermediary product which the artist secretes with all his creative being and which he has to place, to encrust, to impregnate into the pictorial stuff of the painting,” said Klein. His monochrome blue paintings can be read as a satire of abstract art, because they not only have no motif, but they have nothing at all, just “emptiness”, as the artist himself maintained. But they can also be interpreted in the opposite way. Seeing as Klein was genuinely fascinated by mysticism and concepts of the infinite, undefinable and absolute, his decision to use a single deep, suggestive tone of blue can also be seen as an attempt to free the viewer’s mind from all imposed ideas and let him or her rise in free flight. Because, as Klein believed, lines in paintings are “prison bars”, and only colour provides a path to freedom.