Giving voices

An exhibition by Erkan Özgen

30/01/2019

“He always says: ‘I want to give voice to the people.’ He wants to create a space where people can speak,” says Hilde Teerlinck, the director of the Han Nefkens Foundation, about Erkan Özgen, whose exhibition Giving Voices she has curated and which is on show until February 17 at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.

Özgen, who lives in the predominantly Kurdish city of Diyarbakır in Turkey, is a mature and compelling artist, although he is not yet very widely known in Europe. Born in 1971 in Derik, Turkey – an area that has long been the scene of violence and unrest – he confesses that as a child he witnessed too many events that were not appropriate for a child to see. However, having had the opportunity to leave and settle in a calmer place, he has nevertheless remained in conflict-ridden southeastern Turkey, a place where there is never peace. Teerlinck quotes Özgen: “He decided: ‘I want to live here, and I want to construct a life here. Even if it’s difficult. We need freedom, we need a space where we can talk about this, and art can offer this space.’” Özgen has remained because he is convinced that the area needs contemporary art, and he has also remained in order to report very directly to the rest of the world about the current reality in the Middle East. “Do you think that art has the power to change something?” I asked him via e-mail. He replied: “You are actually asking me a question that I constantly ask myself but have yet to answer. I do believe art has the potential to induce change, but the extent of the effect is dependent on the different socio-political landscapes. My interpretation is that art contributes to change in multi-faceted ways. A lot of people have told me that my works have affected them on a very personal level. I value the potential of art in synthesising this personal effect into collective resistance rather than art insisting on a definitive structure of reshaping and directing society.”

Fundació Antoni Tàpies director Carles Guerra emphasises that the location of Giving Voices is not a coincidence, reminding me that, despite his influential status, Tàpies (whose work can currently be seen in the foundation’s exhibition The Political Biography) chose to stay in Spain during Franco’s dictatorship. “He decided to live in Spain. Not because he was compliant with the Franco dictatorship, but because he really wanted to become the voice from inside. Erkan Özgen and Tàpies are united by a contemporary art practice that emerges in difficult conditions. Even now, we see areas and regions where contemporary art is not taken for granted.” When I ask Özgen himself on the significance on the location of where Giving Voices is taking place, he refers to his meeting with Antoni Tàpies: “I had the great chance of meeting Antoni Tàpies back in 2009, in Barcelona, at an exhibition of works produced through the Can Xalant artist exchange in Mataró, Spain. We had been introduced because he wanted to talk to me about my work Origin, and we ended up having a very friendly conversation. Unfortunately, our paths did not cross again, but having my solo exhibition at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies feels like a second encounter, and it means a lot to me. Tàpies used the surface of his paintings to mirror traces of human conflict, and when I look at his work, I see an artist who needed to express his experience of violence. I identify greatly with this sentiment, as my own works are my own investigations of human violence. It is a great honour for me to see that Giving Voices is being shown under the same roof as exhibitions of Antoni Tàpies’s work. This time, our works are conversing with each other.”

Özgen studied painting at Çukurova University and graduated in 2000, but he has chosen video installation as his preferred form of expression. His art focuses on war and pain and the scars they leave. “He wants to show the reality – what it really means. Violence, war – what do they provoke in society, in our development?” says Teerlinck. One might say that for Özgen, the screen is like a magnifying glass that reveals the footprints of horror on victims’ faces and in their minds. In this exhibition, the alienation of television news segments is transformed into direct confrontations with reality; viewers suddenly realise that they feel a human, emotional link with the heroes in his artwork, who, unlike the abstraction of the news, are in fact real, living people.

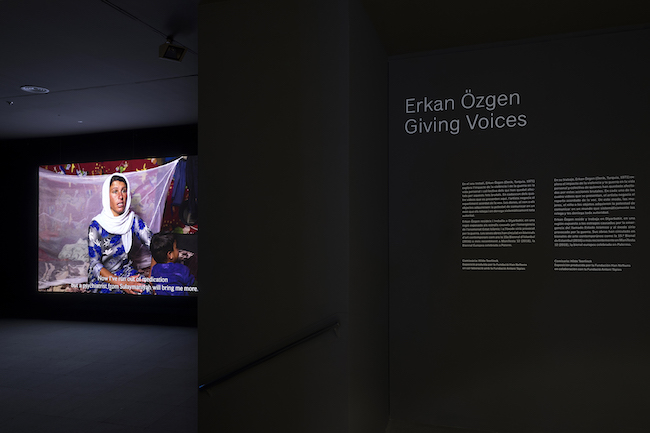

Erkan Özgen. GIVING VOICES. Wonderland, 2016, 3'54'', single - channel HD video projection, color, sound

One of the four video works in the exhibition is Wonderland (2016), which was also shown at the 2017 Istanbul Biennial curated by the artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset. In it, the 13-year-old deaf and mute boy Muhammed, who fled from Syria and ISIS with his family, tells his story using hand gestures and body language. I do not believe it too ambitious to compare the drama in this video to a modern-day Guernica. The video lasts less than four minutes, but it pulls the viewer into the same kind of hell that the Chapman brothers created in their legendary installation Hell. Their construction, however, is an artistic visualisation, while Muhammed is very real.

Regarding Wonderland, Özgen says: “(..) it’s important to realise that the tragedy in the Middle East continues.” This is the present day, in which Muhammed is still trying to hide in a corner of the room whenever an airplane flies overhead and panics when he sees bearded men, because he associates them with ISIS fighters. The terror and horror that has accumulated in his small, fragile frame erupts almost like an explosion. Yes, what takes place on the carpet-strewn floor of his family’s temporary home with its shabby green walls is truly like an explosion – this is the reality of today’s Middle East. Muhammed’s body language requires no translation; it is understood by all.

ERKAN ÖZGEN. Wonderland (fragment). 2016, 3'54'', single - channel HD video projection, color, sound.

Wonderland, which has become one of Özgen’s most recognised works of art, takes on additional power at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies because it becomes a part of a larger story. In the next room, Purple Muslin relays the artist’s conversation with women of the Yazidi minority forced to leave their homes because of their religion. They speak with Özgen in the Ashti refugee camp in northern Iraq, talking about their lives and how they feel about what they have experienced. They do not concentrate on a detailed description of past events; instead, they talk about what life has been like afterwards. The women reveal the eternal scars left by the brutality they have witnessed: “We have lost our minds. I swear. I confuse names. I call out to my children at least ten times, and I call the little one by the elder one’s name. I must be out of my mind. (..)”; “I take medication three times a day. Now I’ve run out of medication, but a psychiatrist from Sulaymaniyah will bring me more. I take it in the morning, in the afternoon and in the evening. When I don’t take it, this boy can’t make a sound, otherwise I might kill him.”

The women look into the viewer’s eyes – they are young and old, surrounded by a stereotypically Eastern sea of bright, lush scarves, shawls, fabrics, pillows and carpets. They are faces and characters on the large screen, a screen whose visual aesthetic is fascinatingly beautiful and perfect. But what must a mother have experienced in order to forget the names of her children...? “What did we do? What did we steal from them? What wrong did we do?” asks one of the women. These conversations – or, more precisely, answers during an interview that reflect the full spectrum of pain and sorrow – show what war and suffering does to individuals and communities alike. They are lost. Lost because they are unable to find and do not know anything about their loved ones. Lost because they are no longer the people they used to be.

Aesthetics of Weapons (fragment), 2018, 4'50'', single - channel HD video projection, color, sound, video produced by the Han Nefkens Foundation

In the context of these two works of art, Özgen’s newest video work, Aesthetic of Weapons, is a shocking contrast. It is a narrative about a man and his revolver, about how weapons become a legitimate instrument in the battle for security and freedom. The viewer does not see the face of this man, who is a policeman – only the revolver and the hands holding it. It is almost with tenderness that he holds the weapon, yet his voice betrays a delight in the power that the weapon provides him. He tells about how he got the weapon, about the reactions of others. The video shows him reloading the gun, aiming, taking it apart and putting it back together again. While Muhammed’s inarticulate shrieks of horror and the sorrows of the Yazidi women echo somewhere in the background, this man admits to being in love with one of the instruments of death. Just like the cannons in The Memory of Time, the first and final work of art in Giving Voices (visitors cannot leave the exhibition without encountering it a second time).

ERKAN ÖZGEN. GIVING VOICES: The Memory of Time, 2018, 12'22'', single - channel HD video projection, color. Exhibition view

Özgen created The Memory of Time in 2016 while at the Safe Haven Helsinki artists’ residence in Suomenlinna, Finland. The 18th-century fortress in Suomenlinna is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a popular tourist destination. The artillery displayed there is a highlight; people immortalise their holidays by taking pictures in front of the historical monuments. In this video Özgen, who has personally seen tanks and cannons enter another site protected by UNESCO, namely, the Sur historical district in Diyarbakır, speaks with people he meets at the Suomenlinna fortress and asks them provocative questions. The text accompanying this work poses a rhetorical question: will the cannons at Diyarbakır also one day be protected by UNESCO?

The idea for this exhibition was initiated by the Han Nefkens Foundation, which also produced two of the video works displayed at the exhibition. Purple Muslin was first shown last summer at the Manifesta nomadic art biennial in Palermo; Aesthetic of Weapons premieres now in Barcelona. The art collector Han Nefkens writes in the exhibition catalogue: “By watching Purple Muslin, these Yazidi refugees enter our lives, and I can hardly think of any other group who deserves our attention more then they do.”

What is the role of art in today’s society? “I believe we live in a time where artists do not take responsibility for direct social action. In fact, the art world seems to be an echo chamber where matters can be discussed and art can be made about certain issues but without any accountability for whether they have an effect outside of the bubble or not. An inconsequential number of artists are caught up in the politics and cause and effect within the bubble. Nevertheless, works of art seem to have a way of contributing to the general shift in cultural imagery, which eventually leads to societal shifts,” says Erkan Özgen.