The beloved and hated Gustavs Klucis

10 must-know things about the avant-garde artist

22/07/2019

Constructor of things and Constructivist, political artist and avant-gardist, understood and misunderstood – is how one of the most influential and prominent artists of the 20th century, Gustavs Klucis, was and still is regarded. His contribution to the development of modern and contemporary art is undeniably remarkable, but the facets of his personality still remain entangled. A pioneer of photomontage, Klucis appeals with his broad array of artistic creations and the true faith he had in what he did. For him, politics and art became one – an absolute greatness permeated with trust and love.

Through 25 August, Estonia’s KUMU Art Museum is hosting the grand exhibition Gustavs Klucis: Russian Avant-Garde in the 1920s-1930s, which covers the artist’s entire creative career. The exhibition includes Gustavs Klucis’ works from his early Constructivist stages and experiments up to his more political art pieces. The exhibition accurately reflects the life of Klucis, step-by-step discovering intimate details and showing the powerful art that he created to be perceived as light, understandable, and indeed admirable.

Gustavs Klucis was born in Latvia

Although several art history and internet site sources mistakenly claim that Klucis was born and raised in Russia, he was actually born in Latvia near the town of Rūjiena.

Gustavs Klucis was born on 4 January 1895, in a poor family of farmhands consisting of six sisters and brothers. Despite living in near poverty, he attended Apškalni Elementary School and then studied at the Valmiera Teacher Seminar, which is where he gained his first basic knowledge of drawing and painting. From 1913 to 1915 Klucis studied at the Riga City Arts School under the great Latvian painters Janis Rozentals, Vilhelms Purvītis, and Jānis Roberts Tillbergs. He continued his studies at the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts in Leningrad (now – Saint Petersburg) until the First World War, when Klucis was mobilised in the Russian army and served in the 9th Latvian Riflemen Division. In 1917 he also took part in the events of the February Revolution and later on, in the Bolshevik October Revolution.

From 1918 onward, Gustavs Klucis lived in Moscow, where he continued his studies and developed a successful professional career.

Klucis studied under Kazimir Malevich

From 1918 to 1921 Gustavs Klucis studied at the legendary VKHUTEMAS or ‘Higher Art and Technical Studios’ in Moscow, which was the most influential of the Russian state’s art and technical schools. Founded in 1920, all of the workshops were established by a decree issued by Vladimir Lenin himself, with the intention of ‘preparing master artists of the highest qualifications for industry, builders, and managers for professional-technical education’ (for more on this topic, see: 100 years of avant-garde). At the time, the school was quite similar to another popular modern art institution – German Bauhaus. The school brought together the brightest Russian modern artists of the era, including Vladimir Tatlin, Naum Gabo, and El Lissitzky, as well as Antoine Pevsner and Kazimir Malevich, both of whom were Klucis’ professors.

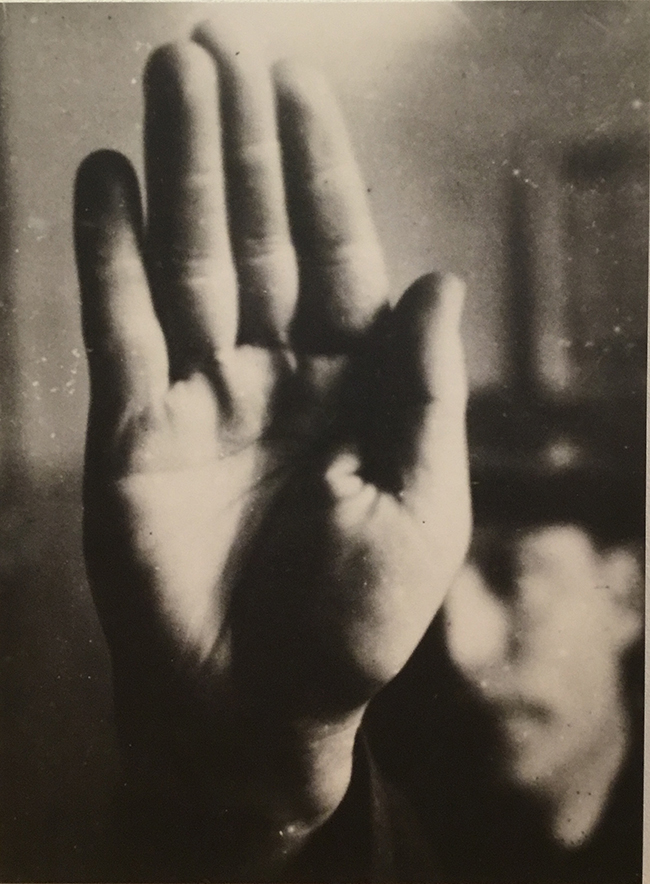

Despite the fact that Klucis was more attracted to the ideas of Constructivism while Malevich had already established the opposite concept of Suprematism, their relationship left indelible impressions on the further development of Gustavs Klucis as an artist. An educational novelty at VKHUTEMAS was the revolutionary photomontage and abstract painting that Klucis studied under Malevich. During that time, Klucis also learned how to embed photographic elements and cut-outs into his paintings, as well as mastered the medium of collage-making, which would become a cornerstone of his career.

,%201930.jpg)

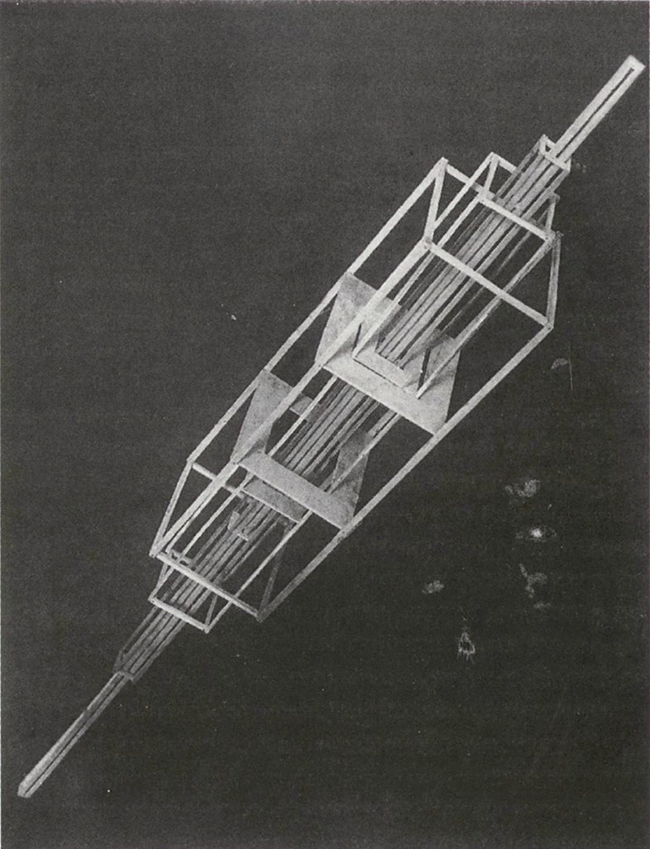

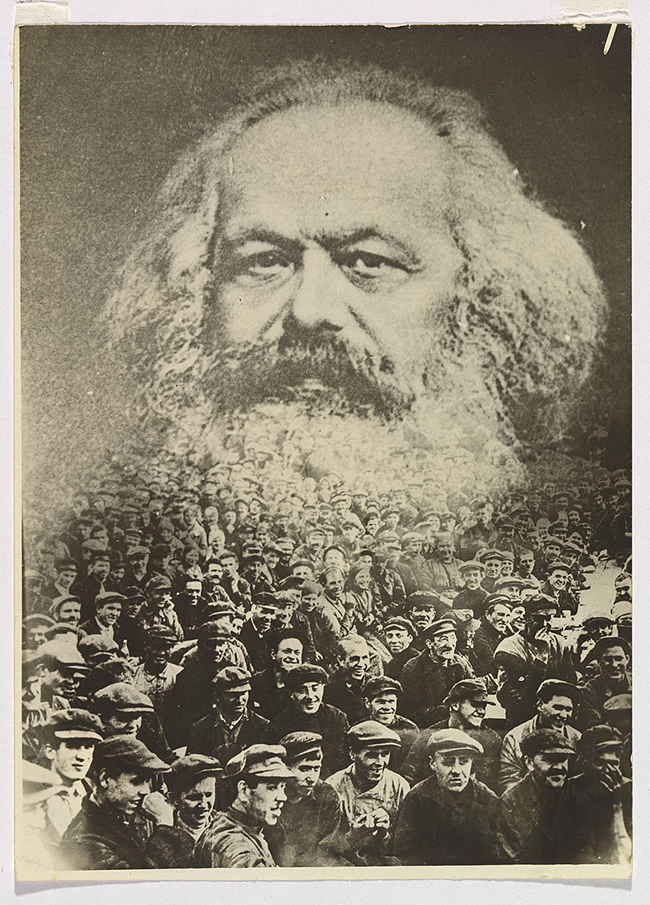

A true communist at heart

Yes, Gustavs Klucis was a sincere believer and enthusiast of communist ideas, and this is clearly reflected in his oeuvre. He was fascinated by the revolutionary ideas of Vladimir Lenin, which allowed him to experiment with combinations of various materials and media –the transformation of simplicity into an artwork corresponded to the order of ‘new art’. Klucis’ interest in Constructivism was in total harmony with the concept of the technicality of art, and later on transformed into a more radical form of political art when he began producing propaganda posters.

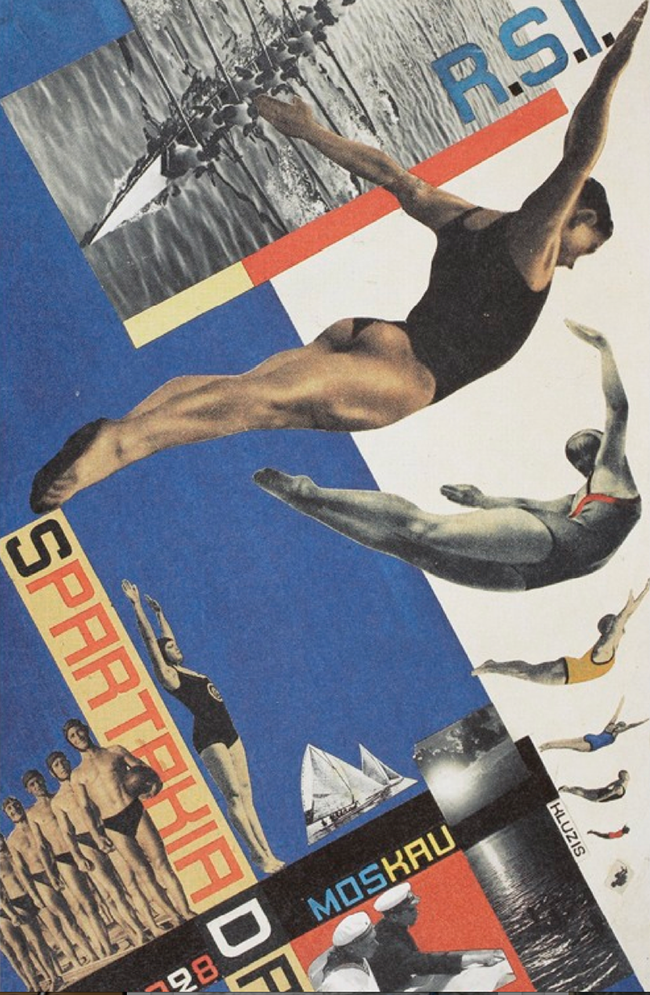

In 1920 Gustavs Klucis joined the Communist Party; at the time, he was very much interested in linking political thoughts with the Suprematist form of working, which he put into practice by using documentary images of Lenin, Trotsky and, finally, Stalin. In 1928 he joined ‘Oktyabr’ (Октябрь), an association for leftist artists whose aim was to promote the tendencies within class-proletarians and to present them as three-dimensional art.

A pioneer of photomontage and one of the brightest avant-garde artists in the Soviet Union

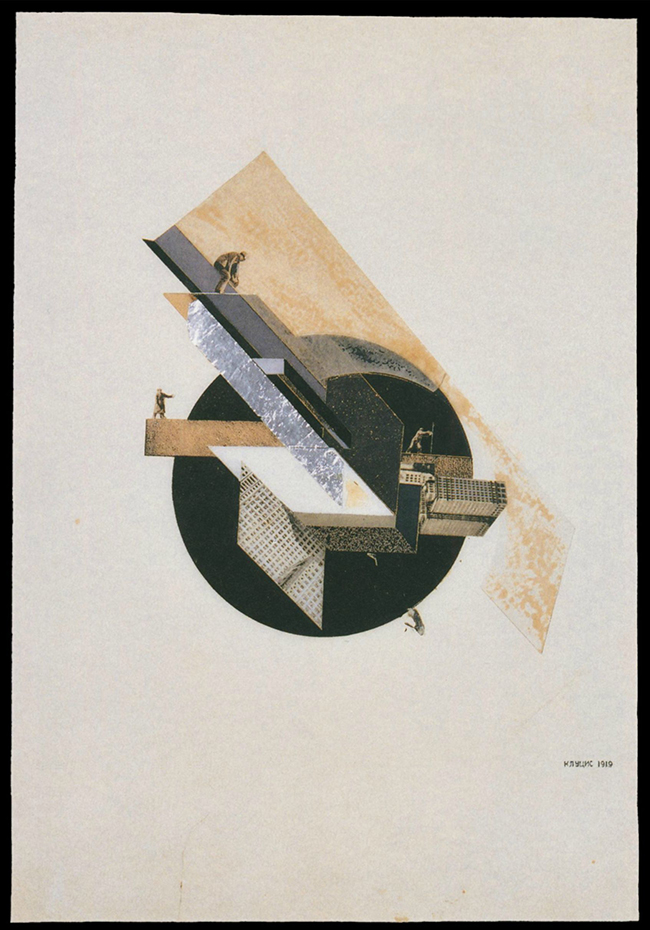

Photomontage as an artistic expression had been initially developed in Berlin around 1918, but it was Gustavs Klucis who brought this art form to its peak. In 1919 he created his first photomontage entitled Dynamic city, in which photography was used as an element of construction; by the early 1920s, Klucis had become a pioneering developer of photomontage. Later on, this artistic process was adopted by many other Russian avant-garde artists and used for different graphic purposes supporting the ideology of communism.

The first books and magazines with Klucis’ photomontages were published in 1923 – around the same time that Alexander Rodchenko was experimenting with the same medium. By 1924, Klucis had been assigned his own camera and developed a unique style – for him it was a new form of experimenting within the limits of propaganda art, but for others (such as Rodchenko), it was a stimulus to continue developing this manner of art.

In 1931 Gustavs Klucis wrote the theoretical article Photomontage as a New Problem in Agit Art, which has become a renowned handbook for this technique.

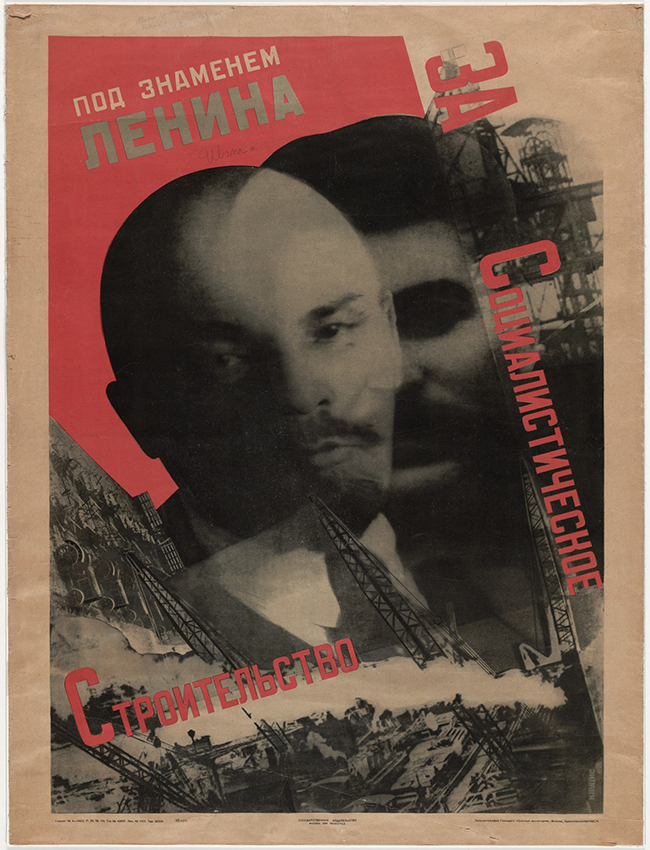

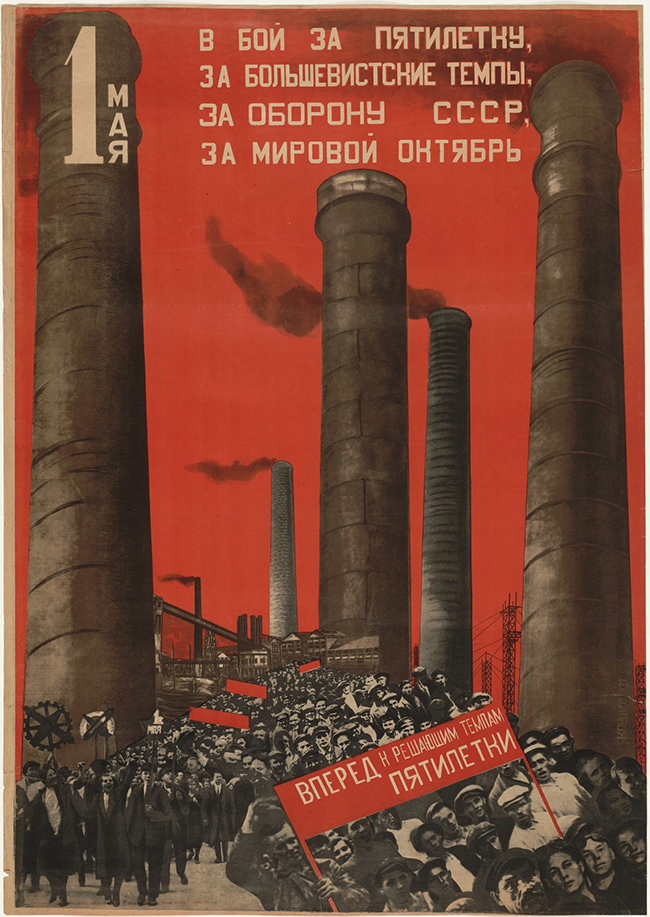

Stalin and Lenin in Klucis’ life

As a representative of the new art form of Constructivism, Klucis focused on reflecting ideology in his art. From the 1930s onward, he mainly worked on the development of propaganda posters for which the protagonist was often Lenin. Tens of thousands of posters featuring monumental slogans and the leader of the Soviet Union, all made by Gustavs Klucis, invited the nation to implement communistic targets and ideas. Lenin, as a character and leader, had a great influence on Klucis’ art; however, after Lenin’s death, it was increasingly dominated by images of Stalin. Gustavs Klucis’ posters were published in the magazines Molodaia Gvardia and Smena, the latter confirming him as the leading photomontage artist of the Soviet Union in 1925. By 1931, Klucis was mostly concentrating on political poster design, and since Stalin’s coming to power, the designs were totally controlled by the ideas that the state expressed. Stylistically, they moved away from Constructivism and towards glorification and monumentalisation of the leader.

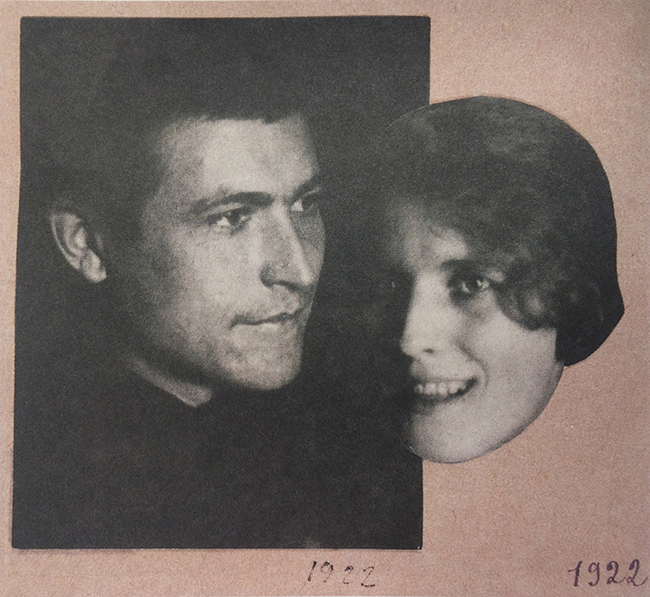

Valentina Kulagina

Probably the most important person in Klucis’ life was his wife, the artist Valentina Kulagina. They met in the winter of 1919/1920, when the seven-years-younger Valentina began to study at VKHUTEMAS. Later she would write in her journal: ‘Medium height, thin, blond, blue-eyed with the right facial features – he made an impression of himself as a man with a strict, even harsh character. (...) He was very diligent, focused, organised… he read and worked a lot.’[i]

They married on 1 February 1921, and would become inseparable allies in both life and art. To be more precise, the life of her husband also became Valentina’s life, and his artistic intentions were often carried out directly through the helping hands of his wife. For example, in 1928, Valentina Kulagina put great effort into arranging the exposition of the Soviet pavilion at the Pressa exhibition in Cologne.

From the mid-1920s onward, Kulagina mostly worked independently, taking an exemplary spot among the top creators of propaganda art. In spite of that, gender inequality played a dominant role in the material welfare of many women, including that of Kulagina, and she would often receive up to five times less money than her husband for the same amount of work.

After the death of Gustavs Klucis, Kulagina stopped working in the creative field, focusing instead on the education of her son Eduard as she worked a salaried job. Valentina Kulagina passed away in 1987, 49 years after Gustavs Klucis.

Klucis’ work as a professor

After graduating in 1924, Klucis became a professor of colour theory and experimental media at VKHUTEMAS. He also became an active member of the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKHUK). While working at the Higher Art and Technical Studios, he and Valentina Kulagina lived on the school’s campus along with other artists, such as Rodchenko, Sergei Senkin, and Varvara Stepanova.

In 1930 Klucis became a lecturer at the Moscow Painting Institute as well as a vice-chairman of ORRP – the Union of Revolutionary Poster Workers.

Participation in exhibitions

During his lifetime, Klucis participated in numerous local and international exhibitions. In 1933 he exhibited at the State Tretyakov Gallery twice, and by the mid-30s had become one of the leading propaganda artists in USSR.

In 1937 Gustavs Klucis created the Soviet Pavilion for the Paris World Exhibition.

Klucis was executed during Stalin’s Great Purge

Despite his immeasurable contribution to the development of propaganda art and the glorification of Soviet leaders, on 17 January 1938 Klucis was secretly arrested during the so-called ‘Latvian operation’ and convicted on the basis of a fabricated indictment of participating in the ‘Latvian nationalist fascist conspiracy’ and engaging in an ‘armed Latvian terrorist organisation’. On 26 February of the same year, Gustavs Klucis was shot at the Butovo firing range in Moscow.

In 1987 Valentina Kulagina died, maintaining belief in her husband’s false death certificate, which she received in 1956 – eighteen years after Klucis’ death. The certificate claimed that Gustavs Klucis has died on 16 March 1944 from a cardiac issue in a work camp in Central Asia. Their son, Eduard Kulagin, finally found out the truth about the circumstances of his father’s death in the 1990s.

Gustavs Klucis’ legacy

Tens of thousands of artworks and propaganda posters by Gustavs Klucis have left an indelible effect on the history of art, in addition to having helped transform the Soviet visual landscape during the 1920s and 30s.

Works by Klucis can be viewed at the State Tretyakov Gallery, MoMA in New York, and many other private and public collections across the globe. One of the greatest collections of Klucis’ works can be found in the Latvian National Museum of Art, which has more than 400 posters, installations and objects in its possession.

[i] Bužinska Irēna, Gustavs Klucis un Valentīna Kulagina STARP PUBLISKO UN PRIVĀTO.