Contemporary art: from Dada to Duda

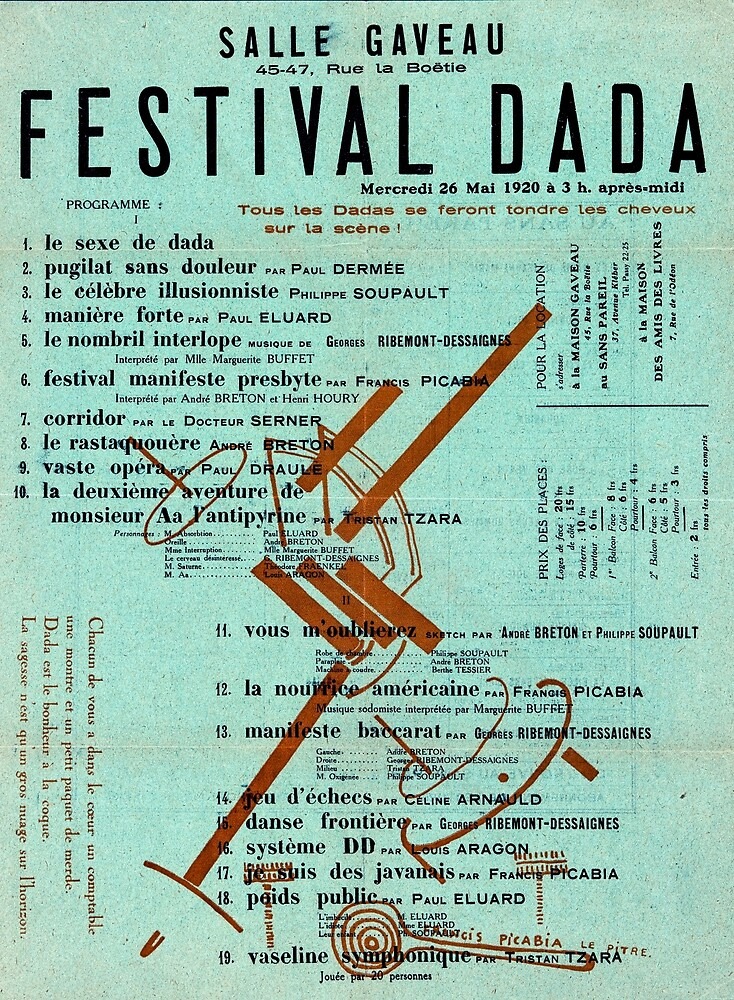

Late in May 1920, flyers announcing a culture event, elevated by its organizers to the rank of festival, circulated in the streets of Paris. The handbills informed its readers that: ‘All of the Dadas will have their heads shaved at the event ... Each one of you has in his heart an accountant, a gold watch, and a small packet of shit … Dada is soft-boiled happiness’, and so on. ‘Festival Dada’ was held less than two years after the end of the First World War in a city that had just recently been bombarded by the Germans with their monstrous ‘Paris siege guns’ (Paris-Geschütz), and at a time when Paris was hit very hard by a printers’ strike. Newspaper publication had halted, and yet leaflets for a festival mounted by the loudest hellraisers in art at the time had been printed. The idea turned out to be quite radical and absolutely revolutionary, despite the fact that the Dadaists shamelessly betrayed the expectations of the public ‒ not a single one of them shaved off their hair on stage. And yet Salle Gaveau at 45 rue La Boétie was packed to the rafters ‒ not just thanks to the movement’s reputation, but probably also because everyone was keen to see the performance advertised as ‘Dada Sex’ ‒ ‘le sexe de dada’. Unlike the barbershop show, it really did materialize. Dada Sex turned out to be a giant white paper phallic-shaped cylinder that managed to float due to the fact that it was fastened to some balloons. The object made its appearance at the early stages of the programme ‒ and stayed to the very end. The spectators, who had had the foresight to arrive equipped with rotten tomatoes, oranges and eggs, did not deny themselves the pleasure of practicing their throwing skills. In short, the whole thing was tremendous fun.

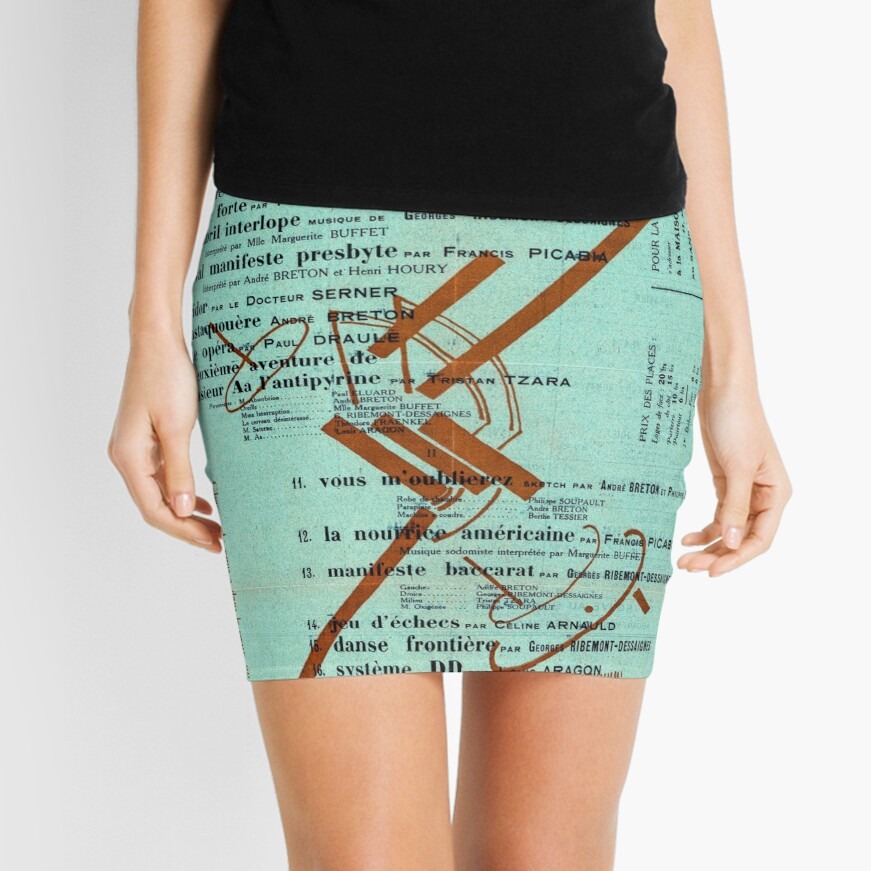

Festival Dada, mercredi 26 mai 1920 à 3 h. après-midi. Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Dada was one of the most radical responses to the absurdity of the well-ordered bourgeois world that had led to the idiotic world war. Everything that had seemed rational, reasonable and progressive up to 1914 had turned into intellectual junk. Or, at least, that is how it appeared to the Dadaists, who started their jolly activities by hiding away from the war in neutral Zurich. Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara were falling over backwards at Cabaret Voltaire to question the holiest of holies, the bourgeois consciousness. Nation, family and the church were now the target of the most absurd, rude and ridiculous attacks by the Dadaists. Which is exactly the same thing that two of their coincidentally contemporary fellow Zürcher, namely, Messrs James Joyce and Vladimir Lenin, were doing at the time ‒ but from completely different perspectives, of course. The former of the two was writing ‘Ulysses’, the latter ‒ his ‘Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism’. Both opuses are genuinely serious in their radicalism. As for the Dadaists, a group of them moved their portable headquarters to Paris; the movement grew in numbers and scope, as well as in glamour, transforming into a feverishly active artistic crowd made up of troublemakers without whom no history of European art and letters would be possible today: Philippe Soupault, André Breton, Francis Picabia, Louis Aragon, et al. These merrymakers and disruptors of social order carried on their activities ‒ albeit somewhat differently and in different areas ‒ after the demise of Dada. Breton became the Iron Chancellor of Surrealism and a Trotskyite to boot; Aragon and Tzara reinvented themselves as confirmed Stalinists; Picabia spent the Nazi occupation years in the South of France without a worry, painting nudes, and after the war was even accused of collaboration. It was exactly the opposite with Soupault, who was arrested by the Vichy regime in 1942 and sent to a concentration camp in Tunisia, from which he eventually managed to escape.

Dada was one of the most extreme and consistent artistic responses to the first global crisis of the bourgeois world order, the First World War. Another artistic response was the Russian avant-garde, which, following a short ‘destructive’ period before the war, found for itself a more constructive path that involved building a new world and creating a ‘new man’. They did build the world, but they did not create the man; in the art market of today, the price range for a Russian avant-garde work is approximately the same as for a Dada work. A Picabia can easily sell for over a million dollars. What was it then that the revolutionaries were fighting for back in the day?

We will attempt to answer this and a couple of other questions in a moment; meanwhile, let us turn our attention to a number of much more recent events. A bit more than a year ago, late in 2019, certain developments in the contemporary art scene caused quite a stir in Poland. It was not provoked by any radical transgressions on the part of artists, by any indecent or scandalous behaviour or lack of respect for sacrosanct principles. Quite the opposite, in fact. The government replaced the head of the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw. The director’s post was offered to Piotr Bernatowicz, a man with scant experience in curating and culture management. He more than makes up for it, however, with his conservative and comfortably right-wing persuasion in the most Polish sense of these words: he is anti-choice, pro-Catholic, traditionalist, and strongly objects to all non-traditional sexual orientations, identities, and other contemporary norms. Prior to this new job, Bernatowicz had for three years held the post of director of the Poznań Arsenal Gallery, earning a certain kind of reputation with a group exhibition entitled ‘Strategies of Rebellion’ (Strategie buntu), featuring, among other things, Wojciech Korkuć’s posters with slogans like ‘Women burn better’ and ‘So you’re gay? Fine, but don’t fuck minors’. Korkuć is a well-known man in Poland; he is a harasser of Germans, an adversary of feminism, and a fan of the extremely right-wing Polish president Andrzej Duda. He produces posters for every occasion; they are quite silly, although not charmingly silly as the objects created by the Dadists in their time. Tzara and Picabia were, after all, geniuses for producing silly art while well aware that the art they were producing was silly. Whereas Korkuć remains arrogantly convinced that his art is extremely witty and thoroughly excellent. Back to Bernatowicz, however.

The outrage caused by the new appointee to the post of director of Ujazdowski Castle Centre was quite serious and international in scope. Everybody who should have their say in the contemporary art world had their say, and what they had to say was only to be expected. After all, regardless of the direct link with the multi-million-dollar art market, regardless of the deep-pocketed crowds at Frieze and similar contemporary art fairs, regardless of the fact that fat cats from Londongrad and Dubai are essentially the main clients of contemporary artists (and particularly art curators and dealers)... to cut a long story short, regardless of all these things, contemporary art is leftist. It is not just that it positions itself as left-leaning; no, it truly is ideologically left-oriented. It was born inside the leftist revolutionary mindset; it became part of the left-wing political discourse (in the West, of course), and as such, it is all about left-liberal values. There is a caveat, however: it is in favour of the leftist values belonging to the political and cultural mainstream in the West. In short, contemporary art is pro-mainstream and also belongs to the actual mainstream. And those who are against it are troublemakers and inciters. Also, dangerous madmen. Only a genuine professional with a wealth of experience in their area can be the head of a contemporary art institution today, just like for a bank or perhaps a governmental department. A dilettante would only undermine the fundament of the correct order of things. And so it has come to pass that this pair of conservative traditionalists, Bernatowicz and Korkuć, are now viewed as troublemakers, hooligans, negationists of the established order of things… almost ‒ and I beg your pardon ‒ as conservative Dadaists. To think that back in 1920, people like these two would have shared their outrage at the latest Dada follies over a glass of red wine in a Parisian bistro ‒ or perhaps in the pages of the conservative press. A hundred years on, outrage at people of their ilk is exchanged over a glass of red wine in intelligent, sensible banter at prestigious vernissages, or in the pages of opulently printed art magazines by the very ones begotten by Dada.

As we can see, the last hundred years have changed absolutely everything that has to do with the objectives, tasks and living conditions of contemporary art. Now, this is where we need to take notice of a banal yet significant distinction. Contemporary art is the successor of avant-garde art as an artistic mindset that is the opposite of modernism, although the two are frequently confused. At the dawn of the last century, modernism insisted on autonomy of art and literature. Modernism elevated art to unattainable heights. Modernism turned art into something that most definitely did not belong to the people, even if it made use of elements of mass culture[1]. While scandalous, modernism was still elitist; as often as not, it made a point of painstakingly separating itself from politics. And finally, many modernists did not at all embrace left-wing views: they were either politically indifferent or even leaning to the right ‒ in some cases, sadly, too far to the right and straight into the territory of fascism and Nazism. These modernists were legion: from Salvador Dalí to Louis-Ferdinand Céline, from Ezra Pound to Balthus. There are, of course, exceptions, most notably in the person of card-carrying communist Pablo Picasso ‒ a fact that, apart from ‘Guernica’, had absolutely no impact on his art. He definitely made no effort to mix the apples of his art with the oranges of life. The aesthetic was not political ‒ and vice versa. A misconception, of course, but an artistically fruitful one.

The avant-garde, on the other hand, chose the opposite as its point of departure. For this kind of mindset, the act of art is an act of transforming the social matter of life, even to the extent of radical reconstruction or reassembly. The aesthetic element of this practice is sometimes quite important, yet still secondary. To be precise, it is frequently born as a side-effect of a direct social gesture. Was the ‘Dada Sex’ of 1920 beautiful? Who knows… Perhaps it was ‒ in someone’s eyes. However, it was created for a completely different purpose.

It is exactly for this reason that the ragged and crude avant-garde produced the serious and business-like Bauhaus, Constructivism, etc. These movements inherited the avant-garde’s idea that culture and art ‒ particularly architecture ‒ can transform public life much more profoundly than anything else. The Bauhaus building as a social gesture was much more powerful than any political manifesto could ever be. And in a sense, it is very true. For instance, the so-called Khrushchyovkas, low-cost panel buildings of the Khrushchev era, transform the mindset of its residents in a most powerful fashion; I would even say ‒ not so much transform as manufacture their consciousness, like on a conveyor belt. I am saying this without a hint of judgement or arrogance (myself currently being a resident of a lovely Khrushchyovka). The socialist ‘bedroom communities’ genuinely did contribute to the formation of a weird variety of collectivist spirit among their residents, and even a certain horizontal social solidarity.

After the Second World War, the avant-garde practically disappeared. The disaster perpetrated in the 1930s‒1940s by totalitarian systems focused on rearranging the world according to some absolutely new (or, in the case of Nazism, allegedly absolutely ancient) principles temporarily shut down all talk of future-forming and life-constructing art. Until the late 1960s, if there was a presence of a new kind of avant-garde in the West (not to be confused with modernism pretending to be ‘avant-garde’ and positioning itself as such exclusively in ‘art’; the rest was twopenny-halfpenny), it was not even attempting to pass itself off as ‘artistic’. Situationists, who started their history as an art movement, did not waste any time before they transformed into political performance practitioners; their leader, Guy Debord, banished ‘artists’ and ‘poets’ of any description from the ranks of Situationist International without as much as a blink of an eye. Let’s remind ourselves that these foul-mouthed fellows, known for attacking any potential allies from the realm of ‘culture’, seemed to be the most ruthless when dealing with those closest to their own principles. Debord spewed tons of bile on the already aging Breton and truckloads of spit on Goddard, his peer. The situationists were the new Dada ‒ except the circumstances were completely different than those in the 1920s. They were not merely undermining the foundations but fighting a real political battle ‒ admittedly, with their own means. It is for this reason that the Parisian leftists armed themselves with situationist slogans in May 1968. The events of May 1968 made Debord jealous, of course: nothing was ever done the way he considered correct. The whole thing ended with him cursing Cohn-Bendit and Co, preferring to remain a confirmed marginal outsider. He was right. Despite tactical defeat, the people and ideas of 1968 won ‒ and they created the world we live in today. And this world created the contemporary art that is considered the only possible contemporary art, establishing an unbreakable link between the political regime of left-liberal democracy, its corresponding values, and art.

Contemporary art was dragged out of the backyards and onto the stage, placed right there in the spotlight. And that is when it turned out that, despite the appropriate triumphant drumroll produced by the art market, art institutions and the press, the public could not care less.

And not just the public. The following scandal took place in Slovenia, not long after the Polish one. Here the right-wing government of the populist variety also performed a purge among the art cadres. It was the well-known curator Zdenka Badovinac who lost her job as the art director of the nationally influential Moderna Galerija. Unlike the Polish right-wingers who – apparently due to a soft spot for szlachta-style obliqueness, a throwback to the splendour of the olden days ‒ made an effort to explain away the purge of cultural institutions by referring to cultural traditions, the biased left-liberal establishment, etc., the Slovenian government headed by Janez Janša was a lot more laconic and, in a sense, more honest. The answer to the question as to why fire an internationally acclaimed head of a very local cultural institution, someone who can actually attract interest in the art scene of a small Balkan country, was the following: power in the country had been held by left-wing politicians for a long time, and they had appointed their people; we hold the power now, and we are appointing ours. That’s all there is to it. Nothing helped ‒ neither the protests and open letters signed by international art dignitaries, nor even the fact that there actually was no one to replace Badovinac. I mean ‒ really no one. And that’s even after invoking a deliberate simplification of required qualifications for the post: not even five years’ worth of experience specifically working in the respective area is necessary anymore. This requirement has been switched to five years of general executive experience, plus... a general idea of what the gallery is all about. Anyway, a new head has not been found yet; they have hired an acting director for the time being (the poet Robert Simonišek) ‒ and seem to have forgotten about the whole business. What matters is not appointing someone new, nor even someone from your own political circles ‒ what matters is getting rid of the previous people’s choice. The consequences of all this for contemporary art in Slovenia do not matter that much – at least that is what the local government believes. Right-wing populists in really small countries are much more aware of the actual idea behind all this fuss about contemporary art than the pompous Poles.

The idea is really a very simple one. Contemporary art – almost the main creation of the left-wing order that gradually established itself in Europe in the aftermath of 1968, this new cultural mainstream that embodies the values of tolerance, openness and internationalism – has fallen victim to its own role. Contemporary art has found itself on the frontline of the ‘culture wars’ that started after the fall of communism ‒ or, rather, were started as a substitute for the cultural confrontation of the Cold War. And it turned out to be completely unfit for the purpose; the valiant lone warriors of the Dada era have long become a thing of past. The system of reproduction and operation of contemporary art proved to be firmly embedded in the mainstream cultural agenda of the late capitalism of the 1980s‒2010s. And now late-stage capitalism has launched an imitated war against itself, bringing to life right-wing populism and nationalist traditionalism whose mission is masking both the stagnation of the actual system and its ironclad globalist nature. And I mean precisely that – ‘imitated’: if we take a look at the biographies of today’s right-populist heroes, we will be hard-pressed to find among them any representatives of the social group defined by Marxists as ‘nationally-oriented bourgeoisie’. These are all international financiers, entrepreneurs with wide-range business interests, and so on. A regrouping of forces, a certain kind of reassemblage of the ruling socio-economic and political system has taken place in front of our very eyes ‒ and the areas this process counts among its victims include contemporary art. It has, after all, been supported by the state, big business and the press for the last fifty years, as a result of which the bubble of significance of contemporary art has grown so huge that it ‒ the selfsame art ‒ is now seen as a thing of utmost importance, and not just by the ruling elites but also by the general population. The thing is, since the times of Warhol, Beuys, the Viennese actionists and others, contemporary art has actually transformed ‒ largely and with some important exceptions (particularly regarding political action art along the lines of Pavlensky or Pussy Riot) ‒ into cute handiwork that genuinely interests very few people outside of ‘expert circles’. I am by no means trying to say that through this it has turned into something inferior ‒ not at all. But its social ‒ not to mention political ‒ significance is wildly exaggerated. The real audience of contemporary art is perfectly and accurately shown in the film ‘The Great Beauty’ (‘La grande bellezza’), in the scene of a performance by a contemporary artist dissatisfied with life: Talia Concept (a cruel parody of Marina Abramović), takes a run-up and bangs her head against the wall of an ancient aqueduct somewhere in the suburbs of Rome. The weather is lovely. A couple of dozen socialites, critics, intellectuals and representatives of the social group best described with the very dated term ‘Bobos’ have gathered to feast their eyes on the open-air performance. The naked ‘Abramović’ shocks everybody with her smashed and bloodied forehead. The blood, however, turns out to be fake. The performance artist is also sporting a hammer and sickle shaved into the red-dyed thick growth of her pubic hair. Piotr Bernatowicz would not have liked this one bit. He would have preferred to see a cross instead. Or perhaps the white Polish eagle: the red background would make it look exactly like the national coat-of-arms.

In fact, that is exactly what Bernatowicz ‒ and all the other ‘bernatowiczes’ in countries where rightists have won ‒ should busy themselves with: shaving ideologically correct images into the pubes of contemporary art, replacing leftist heraldry with a right-wing one. But this mission is not without its problems as well.

The new conservative mandarins of contemporary art (we should note that this sentence does not even seem completely wild: if there are ‘museums of contemporary art’, why shouldn’t there be ‒ purely hypothetically ‒ ‘conservative contemporary art’?) must, after all, somehow fill the galleries of institutions entrusted to their care with some content. With exhibits. Shows. Replace the wrong, i.e. leftist, artists who are, furthermore, part of the imagined (and, to an extent, really existing) establishment with the correct ones: ones who are pro-family, pro-church, pro-tradition and in favour of sex that is hetero- and blessed by sacred marital ties ‒ and if possible, performed in the missionary position (closer to the Church again, right?). On the whole, traditional and traditionalist artists are a dime a dozen in the world, their numbers by far exceeding contemporary ones. There are those who, in their free time from work and household chores, paint beautiful landscapes on the weekends. There are the ones who decorate hotels, restaurants, temples and government offices with their production. There are the ones that paint national leaders and businessmen. And there are the ones who draw portraits of passers-by in the street. There are... There are, finally, the ones who simply love painting instead of conceptualizing. And all of them (or almost all of them) are extremely hostile towards contemporary art, seeing it as nothing more than the quackery of impostors who do not even know how to paint or draw properly. So that’s who should be allowed to fill the galleries and museums reclaimed from the art-leftists. And yet... And yet it would not be contemporary art ‒ but despite their conservative values, the right-wing populists have by now perfectly assimilated the idea that there are no contemporary politics and contemporary social actions without contemporary art. And therefore, the thing to do is show and support exactly this kind of art, the contemporary kind – only make it ideologically correct.

Sadly, there really is no one who could fill the gaping hole that would appear if we got rid of the leftist-liberal mainstream of art. No one and nothing. Right-wing contemporary artists are few and far between; this ideology and mindset is not known for lending itself to the practice called contemporary art. Even Bernatowicz, the poor devil, quipped that he could almost count conservative (or non-leftist) contemporary artists on the fingers of one hand: ‘There are five of them in Poland and perhaps one in Belarus.’ Basically, these people have their work cut out for them. But the job of those who will replace them ‒ once the big corporate bosses, bankers, media moguls and the rest of the masters of this life will have grown bored of playing at right-wing populism (and they already are getting weary: see how skillfully they discarded the simpleton Trump – they had a bit of fun and then got rid of him by switching off his Twitter button) ‒ is going to be much harder – practically impossible. And that is when liberalism, albeit in a different shape, will make its comeback. And trendy women and men rocking freakish-stylish multicoloured glasses will once again fill the abandoned contemporary art galleries. And they will have to pretend that nothing has happened, and that contemporary art is the cultural bread and butter of society. Except no one will believe them anymore. And then Dada Sex with balloons will once again make its appearance on the stage. Will it be a phallic-shaped one? Now there’s a question.

[1] To a certain extent, yet importantly with the exception of the international modernist art style known as Art Nouveau, Secession or Jugendstil. However, the dialectics of the elitist and the mass-orientated elements in this phenomenon is a subject for another conversation.

Images from Redbbubble.com. The featured collection comprises 68 products.