Work of art, what are you telling me?

Ēriks Apaļais

I have often heard artists and art historians opine that a work of art should “speak for itself”, meaning that exhibition texts and commentaries by the artist limit the viewers’ range of interpretations as they encounter artworks and go to see exhibitions.

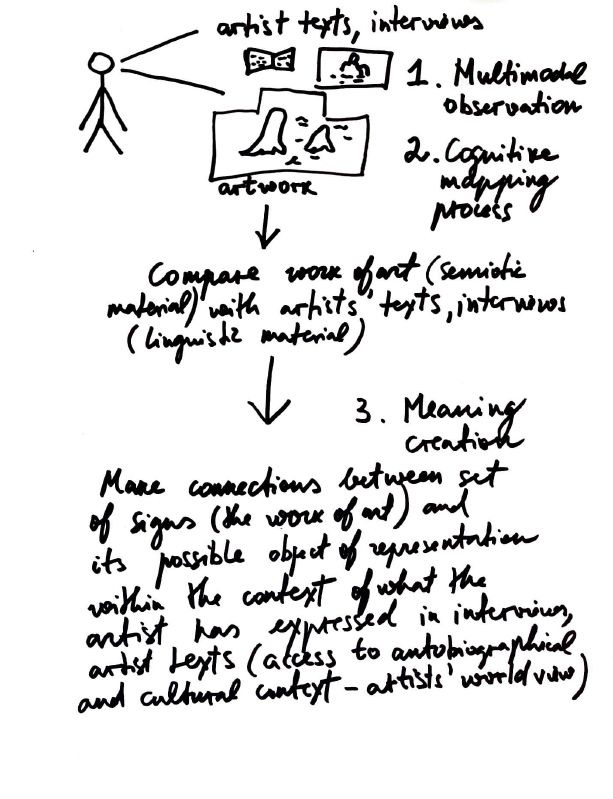

In this short essay, I would like to offer a look at the role that textual resources – interviews with artists, and the texts they have written about their creative practice – play in shaping the meaning of an artwork.

Assuming that the visible form of an artwork can be classified as a visual grammar, the meaning embodied by the form is contingent on the situation (ways of understanding one another and navigating real-life situations) and the cultural context. According to Charles Sanders Peirce, the founder of pragmatics and an early structuralist, images, like texts, are signs. The meaning of these different signs are determined by the relationships between them. [1] In this sense, it can be observed that the disciplines of semiotics (the work of art) and linguistics (the artists’ texts – the titles of their works, interviews, descriptions of their creative activity) interact with one another and that new kinds of signs are created as the two converge. (In this case, the artists working with text as a form of an artwork should be considered separately, as an exception.) There’s a dynamic relationship between the signs, which can be subject to different fluid contexts.

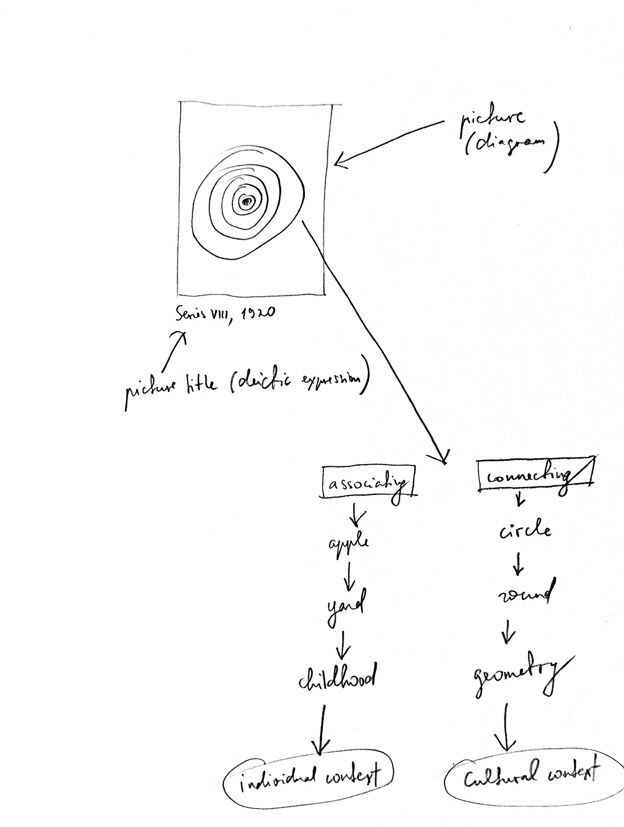

One can distinguish between three kinds of accompanying texts: artwork titles, the artist's textual commentary on their work, and interviews with the artist.

As concerns the title, one could say that it functions as an index finger that either semantically designates the artwork as a set of semiotic signs or serves as a linguistic platform indicating the presence of different discourses embodied in the visual form. Upon encountering the work of art and at the same time familiarizing themselves with its title, viewers should notice and contextualize the paralinguistic message expressed via the formal means of expression (colors, composition) and the title of the work as formulated in language (the text). It follows that the viewer's interpretation results from a multimodal encounter with the artwork as visual material in tandem with the text as legible or audible material.

Whereas scientists find it is important to delimit their object of study, contemporary artists often deliberately avoid the demonstrability of the representable object, often giving or attributing titles to artworks in order to reflect on problems of interpretation, crack jokes, signify the obvious with the goal of arriving at a conceptual generalization of a motif, indicate the methods used to create a work of art (e.g., for works that are created as a series), etc.

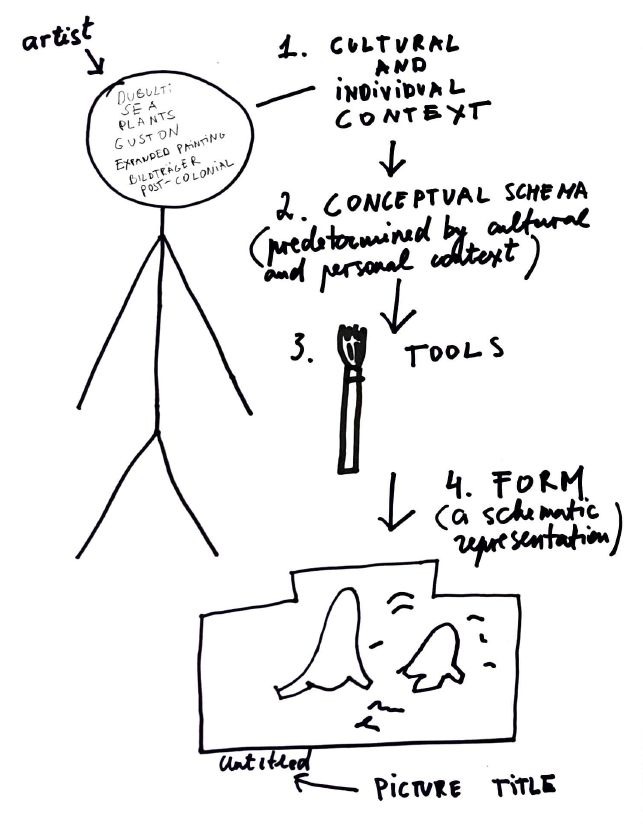

Meanwhile the second and third kinds of texts – namely accompanying texts and interviews – usually provide an insight into the individual context of the artist, such as the circumstances in which they grew up or used to live (e.g., the geopolitical aspect), as well as their broader cultural context, what inspired them, where they were educated, and what they want to achieve in their work.

Assuming that form is entangled with context, the background knowledge that the viewer obtains from an interview with the artist allows them to perceive the meaning of the artwork with greater accuracy. By developing an awareness of the artist’s autobiographical and cultural context, the viewer is able to make more pertinent connections between the set of signs (the work of art) and its possible object of representation within the context of what the artist has expressed in writing. On the other hand, if the viewer will not have made the effort to further their background knowledge of the artist’s work, there is the risk that, as the artwork is encountered in an exhibition, its form will provoke an interpretation that may be partially or completely different from the artist’s message. That is to say, a dissonance may arise between the semiotic form and its function. The visually perceptible signs could become arranged in different sequences, without each individual sign – its layered meaning depending on different contextual conditions – being understood.

As per Benjamin Lee Whorf, a proponent of the theory of linguistic relativity, the words that communicate a message, far from being neutral signifiers, can actually initiate personal associative meanings. [2] In a similar vein, it can be argued that, in order to avoid subjective interpretations, one should observe the fact that, as a sign, a work of art is not necessarily a neutral signifier, but can trigger subjective associative meanings. Thus, if the viewer wants their interpretation to agree with or approximate the artist’s message, they must be armed with prior knowledge. Of course, it is also possible to look at a work of art without prior knowledge, because any kind of contact with a work of art challenges the viewer's preconceptions of the world and invites them to explore new, uncharted territories. One could say that a work of art is like a riddle. As we know, solving riddles serves to improve one’s memory, too.

Returning to the role of background knowledge in shaping the meaning of an artwork, it should be added that such knowledge allows the viewer to approach the artist’s vision of the world, but no matter how hard they try, the viewer’s interpretation can never fully coincide with what the artist is saying. As Edward Sapir, a proponent of descriptive linguistics, explains, a similar misunderstanding during verbal communication may result from the fact that each individual, as a member of a subculture, can be abstracted from culture as a generalized entity. [3] One could say that the worldview of the artist as a practitioner and that of the spectator as a member of a particular subculture is determined by variable individual and cultural contexts. In this way, the language we use to think about art determines the cultural vision of each individual.

According to Henry Widdowson, an authority in the field of applied linguistics, it is possible to familiarize oneself with the situational and cultural context by way of conversation. [4] For example, in a series of conversations held as part of an exhibition, the viewer could pose questions to the artist in an attempt to clarify the perceived intention of the artwork’s message and/or to clarify any ambiguities. Art history texts, on the other hand, enable one to get to know the professional judgment of the people working in the field. This way, the viewer is provided with a kind of conceptual map, which provides them with guideposts towards a more accurate interpretation of the artwork. To be fair, the meanings that the viewer conventionalizes in the course of a conversation with the author of an artwork can be shortened, expanded or adapted to different purposes and other contextual conditions (schools, ideologies), since interpretation is of a processual nature.

In terms of personal experience, I know that when I read exhibition texts or artists’ commentaries, I usually take note of the central concepts that the text operates with. These concepts further serve as meta-elements of a sort, determining the possible interpretative or narrative connections to be made observing the work. If I come across a theory that I am not familiar with, I try to familiarize myself with it by reading specialized texts. Particularly interesting are the moments when the artist reveals an autobiographical facet, because personal contexts usually influence the set of choices made about the material and the conceptual methods and attitudes underlying the work.

In my opinion, the advantage of being an artist-viewer is belonging to a community of practice. I.e., being an artist, it is easier for me to understand the choices that other artists make concerning the material. Since form is not divorced from context and the artist’s formal choices are influenced by their particular cultural context, the formal sequence in which the artwork has been developed shows the way the artist has ordered conceptual references in their mind. These choices concerning the material may further point towards some more nuanced attitudes of the artist, the meta-setting of the artwork, etc. One could say that the viewer has to have a special sensitivity to perceive what is formulated paralinguistically. Artists are often tricksters who love to hide, crack jokes, give hints, and immediately rearrange these into parallel streams of thought. I think that reading poetry could be a good exercise for the audience to cultivate associative thinking, a sense of the space for organizing mental references, and the sensuality that often accompanies the process of making art and thus plays a role in unraveling the meaning of an artwork. As the artist Amanda Ziemele has said, "it’s quite a tangle.”

To be fair, there is a current tendency for artists not to be particularly concerned about the modes of expression that a work of art has, but rather to use art to speak directly and documentarily about socially important topics. This kind of art often has an educational function and contributes to necessary changes in public opinion. At the same time, there is a risk that this kind of art will border on journalism and become didactic. But there’s no arguing in matters of taste, one person likes Walt Whitman, another Emily Dickinson.

Finally, I would like to stress that artists always have the opportunity to make life easier for the viewers with no prior knowledge of art. Particularly, in order to make it easier for them to understand what the artist is saying, artists should preferably express themselves in plain language, without using industry jargon. It would also be preferable for artists to paraphrase the metaphorical into the concrete, thus limiting potentially polysemantic vocabulary. However, the meanings of concrete words also depend on their categorization. That is to say, simple words must likewise be categorized (prototypes, definitions) and contextualized within different cultural discourses for the viewer.

- 1) Peirce, C.S (1998) The Essential Peirce. Selected Philosophical Writings, volume 2. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 394.

- 2) Whorf, B.L. (1956) Language, Thought and Reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 36.

- 3) Sapir, E. (1921) Language: An Introductio to the Study of Speech. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, p. 515.

- 4) Widdowson, H. (2007) Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 54.