There were women artists

Reflection inspired by Katy Hessel’s book The Story of Art Without Men

I am writing these sentences from a place where history is constantly being rewritten, or at least reshaped – the Trapani region in the west of Sicily. Just the other week, from the seabed near the island of Levanzo, an American crew retrieved a new portion of artefacts related to the Carthaginian – Roman battle in March of 241 BC; undoubtedly, this find will improve our understanding of these wars that changed the course of Western civilization. But even more fitting for this article is the fact that after studying the Trapani region and the adjoining islands, British scholar Samuel Butler proposed in his 1897 essay that the true author of the Odyssey was a woman, namely, the Trapani princess Nausica, most likely a daughter of King Alcinous of Scheria. “The more I reflected upon the words, so luminous and so transparent, the more I felt that the Odyssey was instead the work of a brilliant, high-spirited young woman.”

It’s a pity that up till now, this claim has had a small following!

History has always been rewritten, but in the early 21st century we’ve seen an explosion of new narratives correcting historical wrongs. Among the latest is the history of women artists, a topic that has now been bravely taken on by British art historian Katy Hessel in her recent book, The Story of Art Without Men (Penguin UK, 2022). In it, she has put aside male artists in order to put the spotlight on women artists, from the Renaissance to the modern day. The aim of this article is to share some of my reflections on (re)writing history, female subjectivity, and decolonization that I’ve formulated since reading this book.

***

We know that the past occurred and that traces remain, and it is down to historians to order and make sense of them – is how one could summarize the argument of historiographer Keith Jenkin’s groundbreaking book, Rewriting History, 1991. This book argues that the past is a virtually limitless reservoir of traces, but the evidence does not speak for itself. In order to turn the past into history, we need a historian.

Historians aim to be objective in their work, and therefore adopt a certain methodology to try and prevent subjectivity. However, Jenkins notes that History is a personal construct, and therefore it will always include personal bias. Jenkins notes that truth is always created and never found. It does rely intensely on interpretation and rhetoric, although it does use real historical pasts. It is up to historians to decide which facts are significant, and this choice is controlled by the meanings historians give to their facts.

Jenkins argues that there is no centre in History because of the inevitable role of bias. This means that everything is biased because it all comes from someone’s point of view, and this someone would have been inclined to write in a certain way. This again links to truth because one person’s bias is another’s truth – we have already established that truth is created. Say, for example, it was Ernst Gombrich’s truth when he rather shockingly (though perhaps unsurprisingly for the mid-twentieth century), included only one woman artist in his gigantic 650-page book The Story of Art, 1950. From today’s perspective, it certainly looks like patriarchal bias.

Ultimately, according to Jenkins, the role of the historian in making history is irrefutable – without him/her there is only the past and no history.

Katy Hessel at The London Library © Ameena Rojee

***

In following Katy Hessel’s launch tour in the United States for her book The Story of Art Without Men through her Instagram stories, what stood out for me were the overcrowded rooms wherever the book was presented – Boston, New York, Washington, San Francisco… I imagined this is what it looked like when Oscar Wilde went on some of his famous American tours. The difference is that Wilde was a controversial writer of fiction, whereas Hessel is an art historian. Sure, it makes sense that, especially in America, the “Me, too” movement has created fertile ground for an all-woman take on art history. I, however, attribute this fascination of the public to one of the reasons for history’s “epistemological fragilities”.

According to Jenkins, History remains a personal construct, a “manifestation of the historian’s perspective as a narrator”. This is one of the aspects that makes Hessel’s book so relatable and readable – from the very onset, she explains her personal motivation on writing this historical account, often including “I” in a statement when explaining the choice of certain artist or when elucidating the meaning of some artwork. A woman writer has taken on the grand subject of history and boldly stated her subjective choices. What could be more fascinating than that!

Keith Jenkin’s statement that historians can only recover fragments adds a performative aspect to history writing. The history’s story becomes an artwork in itself. Historians like Hessel become an uncoverer of ruins. We follow her into the depths of a cave where where she then sheds the light of her torch here and there, keeping us in suspense of what else might appear. And, boy, does she uncover fascinating destinies and great art, most of which I never knew before. And, since “ruins retain suggestive, unstable semantic potential” (Julia Hall in Ruins of Modernity), the book is full of jolly anticipation of what might come now that we have both evidence and a coherent story about women artists who produced great art. The future is wide open!

***

As Hessel’s book shows, there is ample evidence of the existence of great, talented women artists over the course of centuries, nevertheless, (predominantly male) historians have dismissed their contributions to the point of making them appear almost fictional. “Women’s difference is her millennial absence from history,” wrote feminist artist Carla Lonzi in her 1970 essay Let’s Spit on Hegel, which is also mentioned in Hessel’s book.

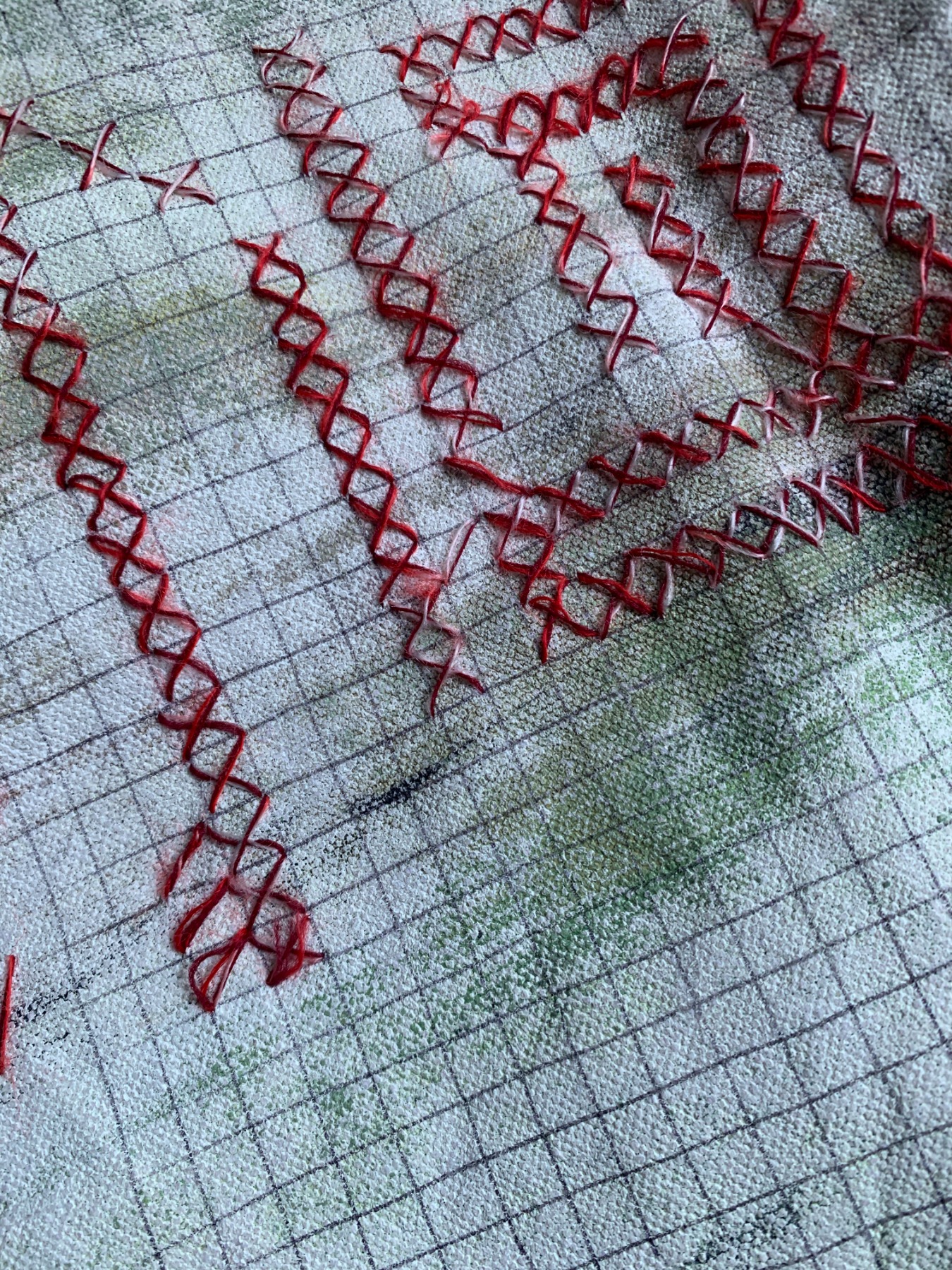

Ilga Leimanis, walk Between Surface and Absorption,

Trapani Sicily, July 7, 2022

Image credits: Ilga Leimanis

London-based artist Ilga Leimanis problematized the dismissal of female labour both in art and life in general by organizing a performative walk titled Between Surface and Absorption in Trapani, Sicily, in July 2022. By walking along the Trapani coastline to the ruins of the old tuna factory, the artist and her companions were leaving traces with their footsteps – which were immediately erased by the waves, much like women’s work has been “erased”. “Woman has undergone the experience of seeing what she was doing destroyed every day.” (Carla Lonzi)

Leimanis describes her project: “The title refers to different states – of staying on the surface or being absorbed within. I’m thinking here of memory and the layering of history, as well as the quality of different materials: some stay on the surface while others are absorbed. Our walk was on the surface, and our footsteps drew lines connecting us with this time and place.” During the walk, Leimanis wore an apron that she had embroidered herself (a technique that her grandmother taught her) – the symbol of domesticity & femininity – to communicate continuity and resistance as well as a “feeling of support from my ancestors.” By making this symbolic protest walk, the artist was claiming women’s right to leave a trace. “Let’s ‘weave places together’ (de Certeau 1984), and become ‘engineers cutting streets’ (Benjamin 1928) through to the past,” was the artist’s call.

As if responding to Ilga Leimanis’ call, Katy Hessel has walked the shores of art history, so to speak, deliberately retrieving traces of woman-made art and turning women’s art practices from decontextualized random ruins into a full-blown story of women’s unique contribution to art.

Ilga Leimanis, walk Between Surface and Absorption, Trapani Sicily, July 7, 2022 Image credit: Anda Klavina

***

It was 2007. I was attending the Venice Biennale as a young art critic writing for Diena (national daily newspaper in Latvia) at the time. The French pavilion was displaying Sophie Calle’s intimate diaries in paper and video, titled Take Care of Yourself, while in the British pavilion, Tracy Emin (the second woman artist ever to represent Britain) had reached the end of her teenage rebellion era and had embarked on more mature exploration via painting. I was too restless in my worldview at that time to truly appreciate the mature insights of these women artists, but looking back, something shifted in me. It had to do with the powerful display of female subjectivity in the public arena. These two artists were communicating what it means to be a woman in this world. And given that it was taking place at the Venice Biennale, the world was confirming that it is interesting and it is important. However, on the male-dominated background, these expositions still stood out as lonely, even bizarre. It felt too personal, not sufficiently “artistic”, and too “feminine”.

As Katy Hessel rightly observes, until recently, there were scarcely any female artists represented in art fairs like Frieze and Art Basel. When it finally started to happen only shortly before Covid, it struck me how used I was to female subjectivity not being represented in places like these. I was amazed at the sense of acceptance and relief that I felt at finally seeing a female perspective – and not as some special exception but as an equal contributor. Hessel’s book is like a boot camp in terms of getting used to seeing female artists and valuing their vision. “Equality is not given. Equality is established when the oppressed starts to act as if she/he is an equal,” states Jacques Ranciere. And Hessel’s book contribution is just that – claiming women artists’ place in history without any excuses.

***

“A novel is in its broadest definition a personal impression of life; that, to begin with, constitutes its value, which is greater or less according to the intensity of the impression. But there will be no intensity at all, and therefore no value, unless there is freedom to feel and say.” Henry James, The Art of Fiction.

For me, The Story of Art Without Men beautifully reveals the centuries-long quest of women to find the freedom “to feel and say.” The freedom to walk the city without being accompanied by a man, the financial freedom to go to Paris, the freedom to present one’s body on one’s own terms, the freedom to be – uncompromisingly.

Hessel often refers to woman artists as powerful and strong. For me, there’s a risk of being trapped within the male definition of power. I agree with Carla Lonzi here: “Existing as a woman does not imply participation in male power, but calls into question the very concept of power.” What we need is not more “powerful” women but the acceptance of women of various kinds as both equal and good enough. For example, in the early 1990s, artist Carrie Mae Weems was driven to produce a series of photographs of Black women doing their daily affairs, i.e., simple, boring and unpretentious life. The radicality of this act was simply showing the traces of women being there. Weems reflected in 2016: “There’s still sort of a dearth, a lack of representational images of women. And not, you know, like strong, powerful, and capable, that kind of bullshit, but rather just images of Black women in the world.”

And that is the radicality of The Story of Art Without Men – the simple statement: THERE WERE WOMAN ARTISTS. This is enough, for the time being.

***

As Katy Hessel denotes, the art of the 21st century is characterized by the decolonization of narratives: various previously dominated groups emerging in the public realm with their own distinctive voice. Hessel has beautifully weaved into her story queer artists as well as artists from America’s black community and Australia’s indigenous community, not to mention artists from Latin America and areas in Asia and Africa. I am aware that there are many more, and Hessel provides access points to the reader for further research.

There are two critical points which stood out for me, though. And they have to do with my East European origins.

Regarding the subjective elements that appear when writing down history, Keith Jenkin notes that it is important to ask: “Who is this history for?” Naturally, in this case it is the Anglo-American audience. It was striking for me to learn of the absence of interest/knowledge about Eastern Europe.

First of all, the Holocaust experience as seen in art is only communicated through Lee Miller’s photography. Important as the photos were in showing the world the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis, I think that instead the book could have honored the work of an artist personally affected by the Holocaust. For instance, Hauser & Wirth recently showed the trauma-informed work of Erna Rosenstein, a Polish Jew.

As a Latvian, I was perplexed as to why Vija Celmins’ name only shows up in a mention in relation to the Los Angeles feminist activities in 1970. Not only is Celmins considered one of the greatest living American artists today, her 1960s paintings were among some of the most potent works in processing war trauma using mass media imagery in line with Pop Art. Her works were bold and striking, but she was not included along with her Pop Art male contemporaries. By dismissing her work now, the book dismisses the experience of millions of displaced people that I, as a Latvian and an East European, can associate with.

I would also name Iza Gencken, Annette Messager, and Sophie Calle – artists who work with the topics of memory, trauma and female subjectivity – as notably missing from the book, not even mentioning the radical Polish, Hungarian, and many more East European women artists of the 60s. Except for the Russian Constructivists, Magdalena Abakanovicz, and Marina Abramovic, there is no one else bringing an East European perspective.

A point that hurt me almost physically was when naming the evil regimes and dictators from the 1930s, the author only mentions Hitler’s Germany, Franco’s Spain, and Mussolini’s Italy. Not a single word about Stalin and the Communist regime! Later, only the fall of the Berlin Wall is mentioned, but no mention of the break up of the Soviet Union or the expansion of the EU. Eastern Europe appears as a shockingly blank territory in this book. From the viewpoint of posh London, the decolonization of Eastern Europe has not taken place.

Is this egregious omission simply the unconscious arrogance of imperial thinking, or is Eastern Europe itself to blame for not being more united and outspoken concerning its heritage? Both are probably at play here. As postcolonialism researcher Homi K. Bhabha states, fragmentation and distrust is the heritage of colonialism. The story of East European women artists (and more) still needs to be written.

I’ll mention some positive developments in this regard. In 2019, the European Parliament condemned the Communist regime alongside that of the Nazis. (I hope art history departments in the UK as well will update their outlook on the 20th century.) Since 2009, MoMA has been conducting the Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) cross-departmental research programme, which fosters multiyear studies of art histories outside North America and Western Europe, with one of the regions being Eastern Europe. Tate Modern has a strong East European representation in their acquisitions board. The London gallery Emalin, which specializes in the young generation, has a strong East European artist list among their offering. Muzeum Susch in Switzerland has stated as their mission to elaborate the oeuvre of women artists from Central & Eastern Europe. “The principal subject of research by Instituto Susch will be works of women artists from the 1960s, 70s and 80s. In our work we wish to focus primarily on avant-garde women artists experimenting with new media and techniques, but also those achieving innovative results using traditional techniques.”

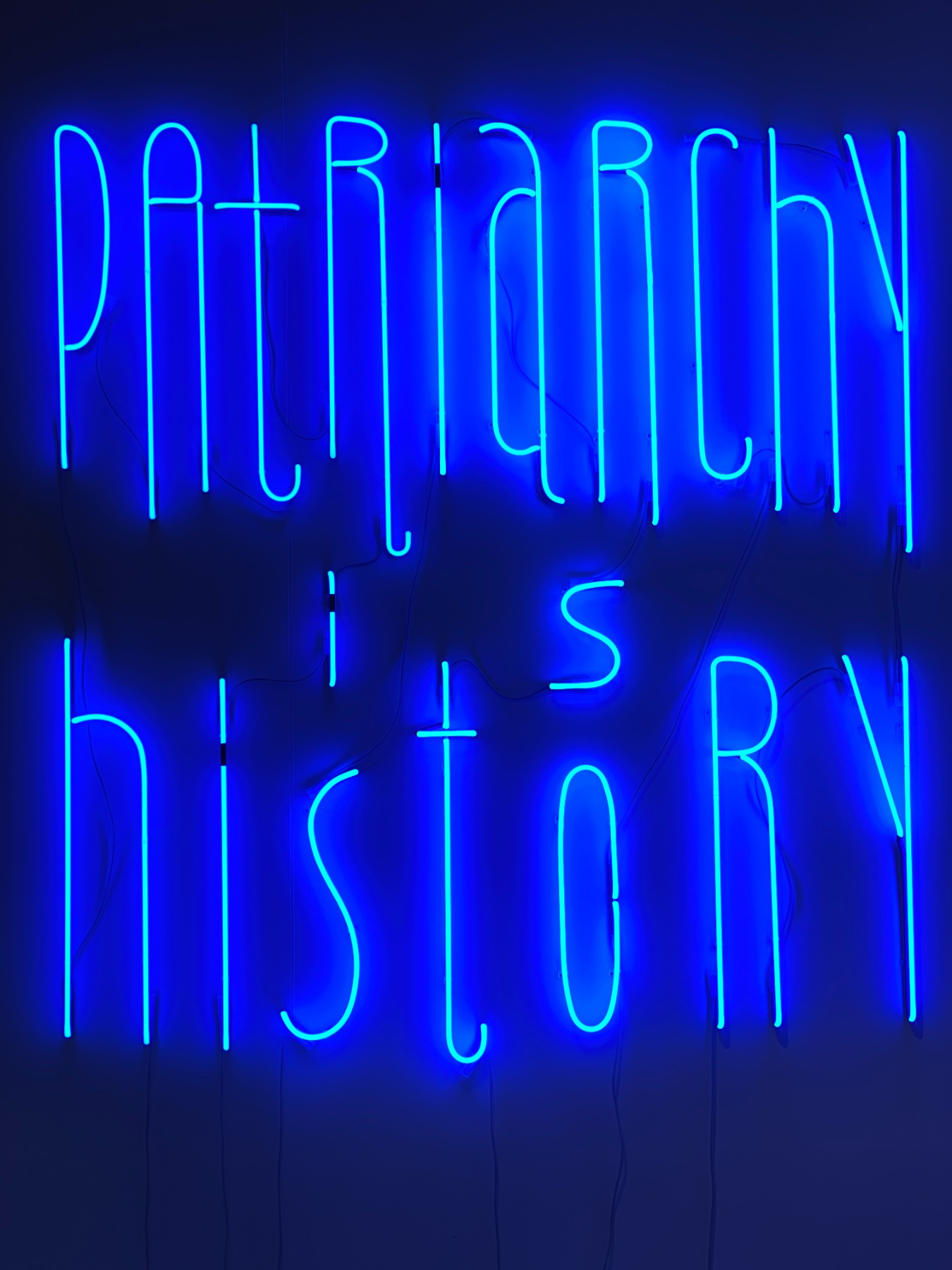

Yael Bartana: Patriarchy is History, 2019. Neon, 198,4 × 185,3 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano. Photo: Anda Klavina

***

Despite these critical points, Katy Hessel’s book is a reason for major celebration. No wonder it has been translated into dozens of languages. The purpose of art is to express what is feels like to be in this world. Here, the sense of existence from a woman’s perspective is accepted and celebrated. The book loosens the patriarchal grip on history. It is an important reminder of the fact that there is no one historical truth, and we should be sceptical if one claims that there is. The writing of history operates like a tidal flow: the sea of facts concerning the past is always there, yet it changes what the tidewater brings to the shore and what a historian chooses to pick up. “We consider incomplete any history that is based on non-perishable traces,” wrote the feminists in 1970. There is always more to history, and Katy Hessel invites us to keep both our eyes and minds open to discovery.

Yael Bartana: Patriarchy is History, 2019. Neon, 198,4 × 185,3 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano. Photo: Anda Klavina