Conflicted in Pastel Tones

An essay on Sandra Strēle’s exhibition “The Night Before” at the Rothko Museum in Daugavpils

Large-scale painting sets in motion a complex web of relationships – not only with the space in which the work is created, but also with the very different space where it is exhibited and encountered by the viewer. Inevitably, such painting invites conflict, beginning with scale itself. Standing face to face with these works, the viewer is physically confronted with the fact that they cannot be grasped “in a single breath”. To take them in requires at once a loosening and a focusing of different muscle groups and mental points to reconcile one’s own scale with that of the painted world. Yet problems of scale are only a starting point. Within the context of contemporary Latvian art, Sandra Strēle’s painting engages in conflict in at least three directions:

1) conflict with the exhibition space,

2) conflict with the artist’s self-image,

3) conflict expressed through Strēle’s distinctive pastel palette.

Exhibition view. Photo: Didzis Grodzs

Conflicted Space

Sandra Strēle has long worked in large formats. This is particularly striking given the chronic shortage of studio space that dogs Latvian artists. Yet she has painted for years as if this lack of space did not apply to her; as if her canvases were conceived and realised in other, less austere circumstances, where one isn’t limited to thinking in survival mode but can breathe deeply and, with imagination, lift the ceiling or push a wall back by twenty centimetres. However, when a large-format painting, created in such imaginatively expanded space, enters the exhibition hall, its spatial logic shifts – for the exhibition space is never the same as the space of creation. The word “conflict” already suggests the potential for new relations: something unsettled, then reconfigured in a different sequence.

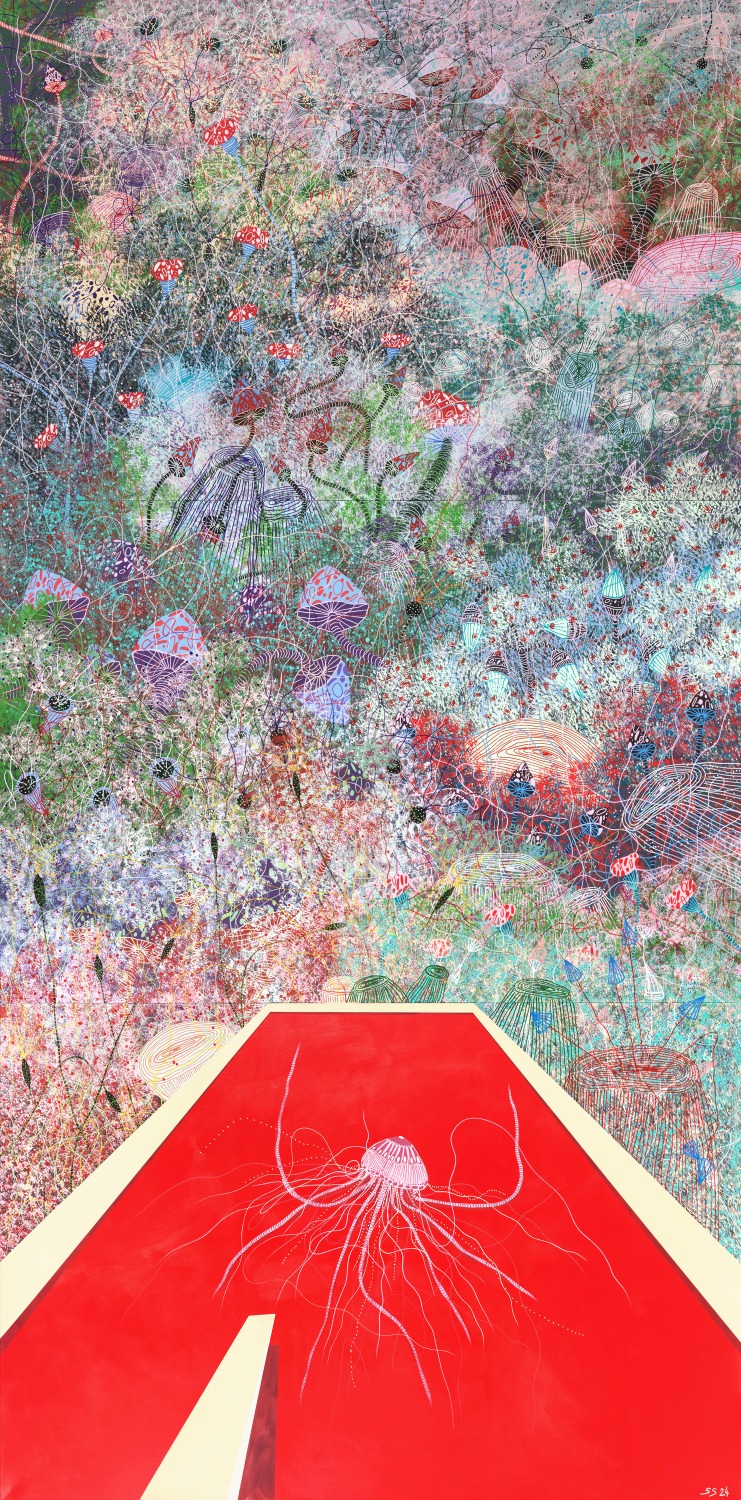

Sandra Strēle. The Night Before. Bleeding Medusa. 405x200 cm. 2024

“The Night Before”, Strēle’s solo exhibition at the Rothko Museum, unfolds in the institution’s second-floor gallery space, where, acting as her own scenographer and curator, she has removed the usual modular coverings and stripped the fortress walls bare. Her monumental canvases, such as “Bleeding Medusa” and “To the Goldfish That’s Always There,” rise to more than four metres and are displayed at a tilt, like a frozen wave looming above the viewer.

Sandra Strēle. The Night Before. To the Goldfish That's Always There. 405x200cm. 2025

This unconventional arrangement is at least in part dictated by the Rothko Museum’s ceilings, yet rather than restraining Strēle, the architecture has prompted her to devise ways of folding the paintings fluidly into the space. The conventional order of “painting on the wall” is further disturbed by small installations: the objects have first been painted on canvas and only afterwards carried into the space as if by an invisible wave or current, escaping beyond the frame.

Sandra Strēle. The Night Before. Tsunami. 200x150 cm. 2025

Conflict with the Artist’s Self-Image

For those familiar with Strēle’s art, water has long been a central element. Until recently, it appeared as constrained, humanly tamed – most often as a smooth, silent pool. Even when overgrown in a distinctly Latvian thicket of brambles, its mirror surface was left unbroken, unruffled by so much as a stray leaf. The lack of human figures in the painted scenes did not mean the absence of a human presence – one could imagine a watchful figure just beyond the frame, carefully tending the pool.

Sandra Strēle. The Night Before. Kick. 20x90 cm. 2025

The first disturbances in this mirror were visible with the onset of the war in Ukraine nearly four years ago, when the pool turned a vivid red. Yet “The Night Before” brings a new turbulence, not only through the scale of its display. This time, the smooth surface is shattered by explosions of energy (Tsunami, 2025; Kick, 2025; Eruption, 2025). The water is no longer flawless (Leafcatchers, 2025). In another canvas, a garden gnome tries to conjure his goldfish from the pool’s depths, while a medusa drifts in a pool of blood. Would it sting if one drew too close? The solitary light in the opposite house’s window stings like the medusa – at once a promise and a rebuff. Will the door open after a knock? Or will there only be a quiet but definite refusal?

Sandra Strēle. The Night Before. Leafcatchers. 150x200 cm. 2025

What has unsettled the once-still pool? In Strēle’s art, water has crossed its boundaries, swelling many times over. Returning home from the maternity ward with her daughter, Selma, Strēle resumed painting on the third day. Motherhood cannot be “set aside” from daily artistic practice; it floods and overtakes everything. Immersion in this new reality, this new routine, produces a shift in the atmosphere, and that shift, in turn, generates waves in the water. One cannot help but become water oneself – to resist would mean suffering seasickness every day. Yet motherhood embodies both the surge of a tsunami and the reshaped self-image of a hesitant, uncertain mother. Even if you are the mother of the Buddha (who appeared to his mother in a dream as an elephant), there are days when the mother faces herself and the world as a tiny plush toy (Mother to Elephants, 2025).

Exhibition view. Photo: Didzis Grodzs

Pastel Conflicts

One of the guiding lights in the sea of contemporary art history is the recognition that socially engaged art, responding to the world’s injustices and hidden power structures, must be ugly. It rejects aesthetics to focus wholly on the ethical: it does not seek to please, soothe, or stand as a self-sufficiently pretty object above a collector’s mantelpiece. Anything deemed too beautiful, unless quoted deliberately, is already suspect.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Latvian painting was mired in decorative despair, as many artists long protected by Soviet-era institutional acquisitions never managed to adapt to the changed reality. Painting became unmoored, free to indulge in glossy female nudes, florals, gilded frames and gleaming lacquered surfaces. As a reaction to this emptiness, the “new simplicity” of Andris Eglītis and Daiga Krūze (in its Expressionist branch) re-established painting’s meaningful connection with everyday life and with attentive observation of nature.

Exhibition view. Photo: Didzis Grodzs

But today’s younger painters are following another path. They are actively engaged with the art market, forming close ties with their own generation of gallerists in Latvia and abroad. Strēle works successfully with The Rooster Gallery in Vilnius, Lithuania. What matters now is that the question of radical form has re-emerged, with decorativeness itself as one of its modes. Many younger painters work as though the traumatisms of daily life, coloured by Latvia’s Soviet and post-Soviet history, were the burden of a middle generation – artists such as Ieva Epnere and Kristaps Epners, Ingrīda Pičukāne, and Krišs Salmanis. And perhaps they are right? Perhaps our most visible social scars have slowly healed?

I do not believe so. The Latvian art world today is the child of an online age – a world no more healed or wholesome than it was ten or fifteen years ago; indeed, one far more openly violent, brimming with misogynistic cynicism. Latvian artists search desperately for their reflection in the distorting mirrors of social media, consoling themselves with a survival-driven self-deception that everything will be fine. If Latvia has no national museum of contemporary art, then so be it. We will do the work ourselves – through active galleries, through self-organisation, through integration with the wider world. And above all, we will rediscover the mysterious beauty of the world, which every generation of artists must interpret anew.

Strēle’s pastel-coloured surfaces, however, suggest something different. They undeniably strive to reveal the secret of beauty, yet refined decorativeness can only flourish when anchored in the awkward notations of daily life. Motherhood here is bramble-covered, tide-ridden, poised on an unstable plank beside a garden gnome. “Perhaps the pink is blood – only diluted,” the artist remarks.

“The Night Before” is a courteous and gentle phrase.

Yet it also heralds something approaching – a temporary state, unstable, uncertain, in-between. The liminal moment before something else, the instant before stepping from the plank. And down there, in the depths, lie not only harmless autumn leaves, but also medusa.

***

Sandra Strēle. Exhibition “The Night Before”

On view till 23 November, 2025 at the Rothko Museum, Daugavpils / 2nd floor, Sector C

Title image: Sandra Strēle. The Night Before. Eruption. 30x40 cm. 2025