The Venice Biennale, with an Odor of Decaying Capitalism

30/05/2013

The descriptor “sporting event” doesn't even apply to the Venice Biennale, but rather to the press. “Ai Weiwei's cocktail evening took place today, it was quite small – did you go?” David Ulrich, a curator and art critic from Berlin, asks me on Tuesday evening at 23.15, as he hands me an orange spritz with ice. We are on the island of Guidecca, in the canal-side cafe Osteria de Botti. Ulrich is organizing an unofficial satellite-show on the art of Prague, and is also working with the Scandinavian artistic duo of Elmgreen&Dragset, who will be unveiling a wide-raging urban art project in Munich this June. The Biennale serves as a convenient time to organize an informal meeting for the representatives of the press that have been invited to Munich. It's the evening before the start of the Biennale's press-preview days, but I feel as if I've already missed all of the important things. I climb back onto a vaporetto, which then takes me back to the directly-opposite San Marco Square. On the way, the boat makes a stop at the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, on which Marc Quinn's gigantic, armless and stubby sculpture gazes in the direction of the searchlight-illuminated Giardini. The sculpture's skin is the color of blueberry yogurt. The Giorgio Cini Foundation, which is located right next to the landing, is hosting a large solo show of Quinn's works; the opening is set for the following day, but apparently, that doesn't apply to everyone, since a group of tipsy people climb aboard – well-dressed (except for brightly-colored trainers that make for comfortable walking), and with emblazoned tote bags on their shoulders that give them away. Evidently, they are journalists and art critics who, a day before the Biennale's press-preview days, are foraying from one secret party to the next.

“That's Ai Weiwei's mother,” I hear a German gentleman behind me remark. The amount of visitors allowed in at one time to Germany's national exhibition, which is located in France's pavilion, is being carefully rationed. Speaking in various tongues, the line of art lovers patiently wait their turn. While we wait, a short film by French artist and film director Romuald Karmakar is being shown in a loop, projected onto the outer wall of the pavilion; it is of a rhinoceros eating hay at the Berlin Zoo. At first, it looks as if it's impossible to even enter the pavilion due to the humongous pile of three-legged stools that can be seen over the heads of those in front of me – they appear to be stretching out in all directions, practically reaching the white wooden beams that support the pavilion's glass ceiling. Ai Weiwei's “Bang” (2010-2013) is composed of 886 stools – considered to be antiques in today's China, where they have long been replaced by plastic and metal versions. As written in the annotation, each stool in the gargantuan installation represents an individual's relationship to the postmodern world, which is developing at the speed of light. When I enter the exhibition, Ai Weiwei's mother is slowly walking through the space, tightly holding on to the arm of her light-haired chaperone. She is accompanied by yet another person, this one filming her every move and uttered commentary in Chinese. Immediately behind Ai Weiwei's sculpture, in the final room, is another of Karmakar's videos – a large-scale, grainy depiction of tree-tops being whipped by a storm. It is the short film “Anticipation”, which depicts the moments before the culmination of Tropical Storm Sandy in October of 2012.

A celebratory opening of both countries' exhibitions takes place half an hour later, on the steps of the directly-opposite German pavilion. In her speech, curator Susanne Gaensheimer (who also curated Germany's pavilion in the previous Biennale) states the phrase that art = freedom, and freedom = art, underlining how important it is to her to show an artist that is banned in his own country (China), namely, Ai Weiwei.

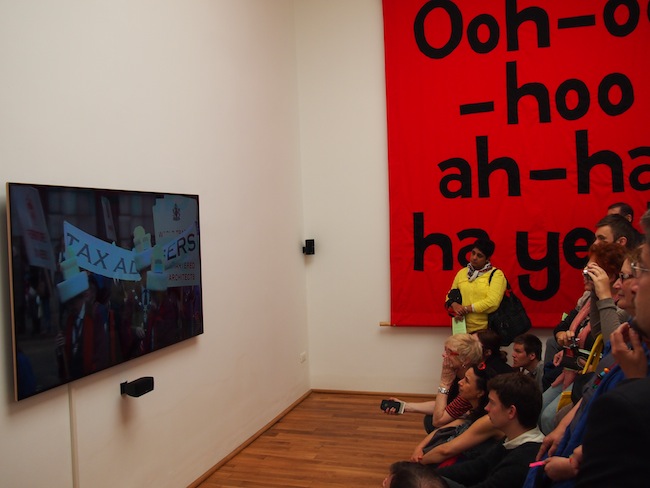

Right between both pavilions is the UK's home base, its exhibition, “English Magic”, having been made by Brit Jeremy Deller. This artist has always liked satirizing the icons, myths, folklore, culture and political history of British society. The narrative of his Biennial exposition achieves a psychedelic mood due to the meshing together of facts with the artist's own imagination. The UK's tax politics meld together with colorfully drawn portraits of politicians, while a video screen shows people, both children and adults, jumping on an inflated Stonehenge, all set to a soundtrack of dance music. In the back of the pavilion, visitors can sip on tea with milk. Deller's works happen to be in tune with those of Moscow conceptualist Vadim Zakharov, whose exhibition in Russia's pavilion is spread out between two stories. Gold coins fall through a shaft leading from the second floor to the first, creating a purple pile on the floor. Visitors are given transparent umbrellas, against which the bright disks pop like hail. It's quite ironic to see that most people grab a handful of the golden coins and stuff them in their pockets.

Trainers are a must, since shortly before noon I have to make a run to the 55th Venice Biennale's press conference, in which the Biennale's president, Paolo Baratta, gives the keynote speech and addresses the issues of nationality's role at the Biennale. In his opinion, the act of participation is what is important to individual countries; for newcomers, it is the opportunity to get on the list of participants. Since the start of renovations in 2011, the Arsenale has expanded, thereby allowing for more space for national pavilions, including some first-timers, such as the Vatican and the United Arab Emirates.

Meanwhile, Latvia's pavilion, which is also in the Arsenale, and whose exhibition brings to the forefront the issue of translating the “Latvian-ness” of art, is imbued with a strong bouquet of exotic aromas leaking in from the adjacent Latin American exhibition – at the center of which are brightly colored mountains of spices. “We all come from some country or other. But at the same time, each country is a part of the world. There are many levels from which to look at nationality. And that's why art is so unique – because it unifies us,” I'm told by an art critic from California as we sit together in a shady spot, eating our sandwiches. In complete contrast to the speed with which the journalists wolf down their lunches, a boat slowly glides by right before our eyes; it is playing Wagner, i.e., the four-hour performance art piece “S.S. Hangover”, by Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson.

Marc Quinn's scultpture, “Alison Lapper Pregnant”

The press line waiting to get in to the Arsenale

The boat which will carry the participants of Ragnar Kjartansson's “S.S. Hangover” performance

The gardens that contain the permanent national pavilions

Ai Weiwei's mother, Gao Ying

Ai Weiwei's installation, “Bang”, in the national pavilion of Germany

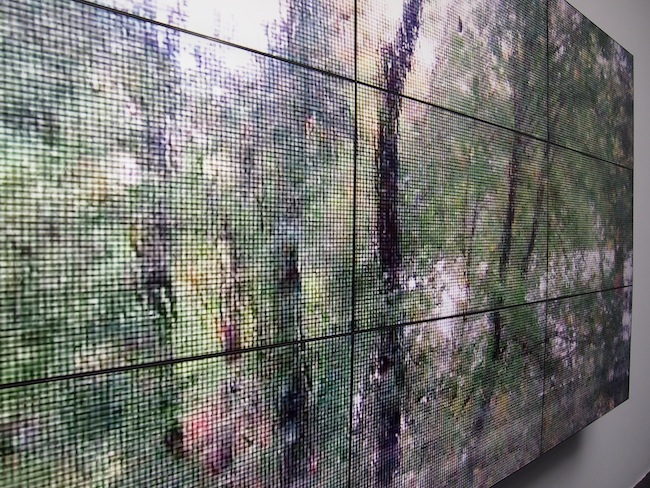

Romuald Karmakar. “Anticipation”, 2013; part of Germany's national exhibition

Paolo Baratta, at the opening of the German and French pavilions

The UK's exhibition, created by British artist Jeremy Deller

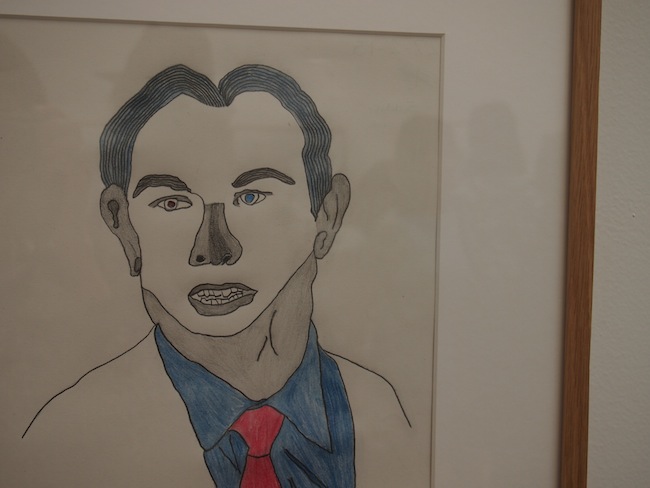

Tony Blair at the UK's pavilion

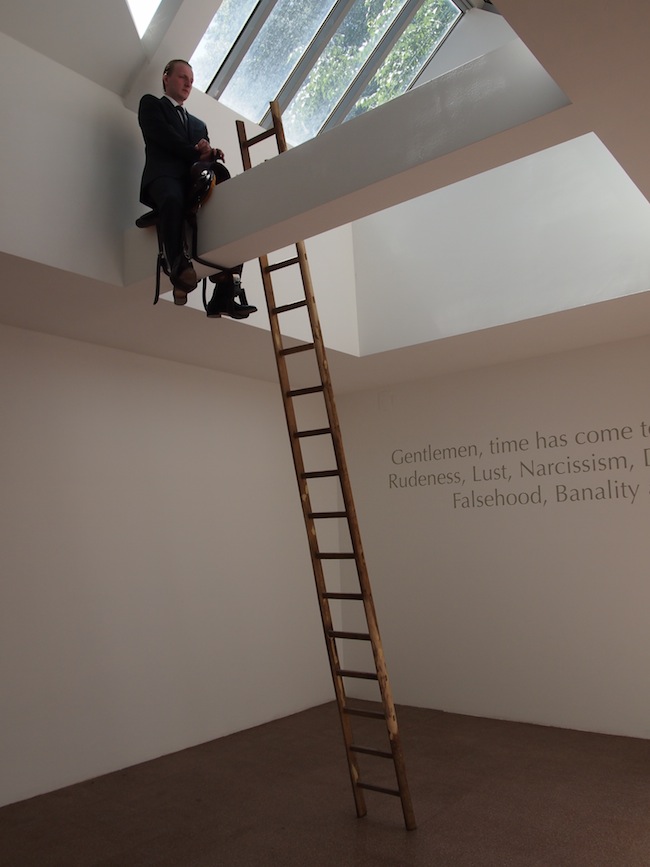

The exhibition in Russia's national pavilion, created by Moscow conceptualist Vadim Zakharov, and curated by Germany's Udo Kittelman. A real person sits in a saddle attached to a ceiling beam as he drops down peanuts

Museum of Everything

Latvian national pavilion

The entrance to the pavilion of the United Arab Emirates, located in the Arsenale

The Latin American exhibition, located in the Arsenale