A dialogue between Kafka and Mowgli

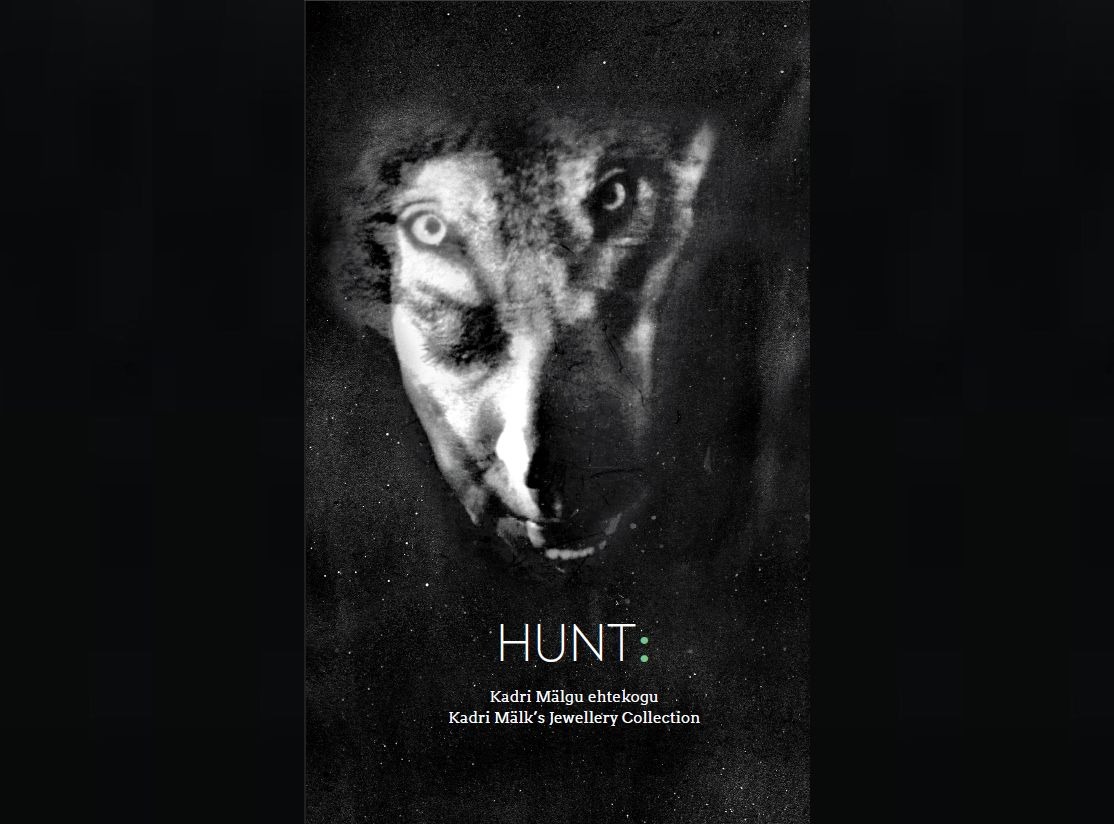

Release of Hunt: Kadri Mälk’s Jewellery Collection, a book dedicated to the impressive jewellery collection of Estonian jewellery artist Kadri Mälk

Creating a collection of art is to a certain extent like creating a fragrance – the search for rare and independent ingredients and new connections and blends. A process that almost borders on the metaphysical, giving rise to a new substance for which there is actually no need but which nevertheless changes the world. In the process of collecting, objects are freed from their partial solitude; their existence up until this point does an unpredictable somersault. “It’s the need to create a new wholeness, to say nothing of a new world of existence, from several or even many differentiated identities and presentations ‒ in the end, nothing is accidental, or occasional,” Israeli art collector Noemi Givon once told me in an interview.

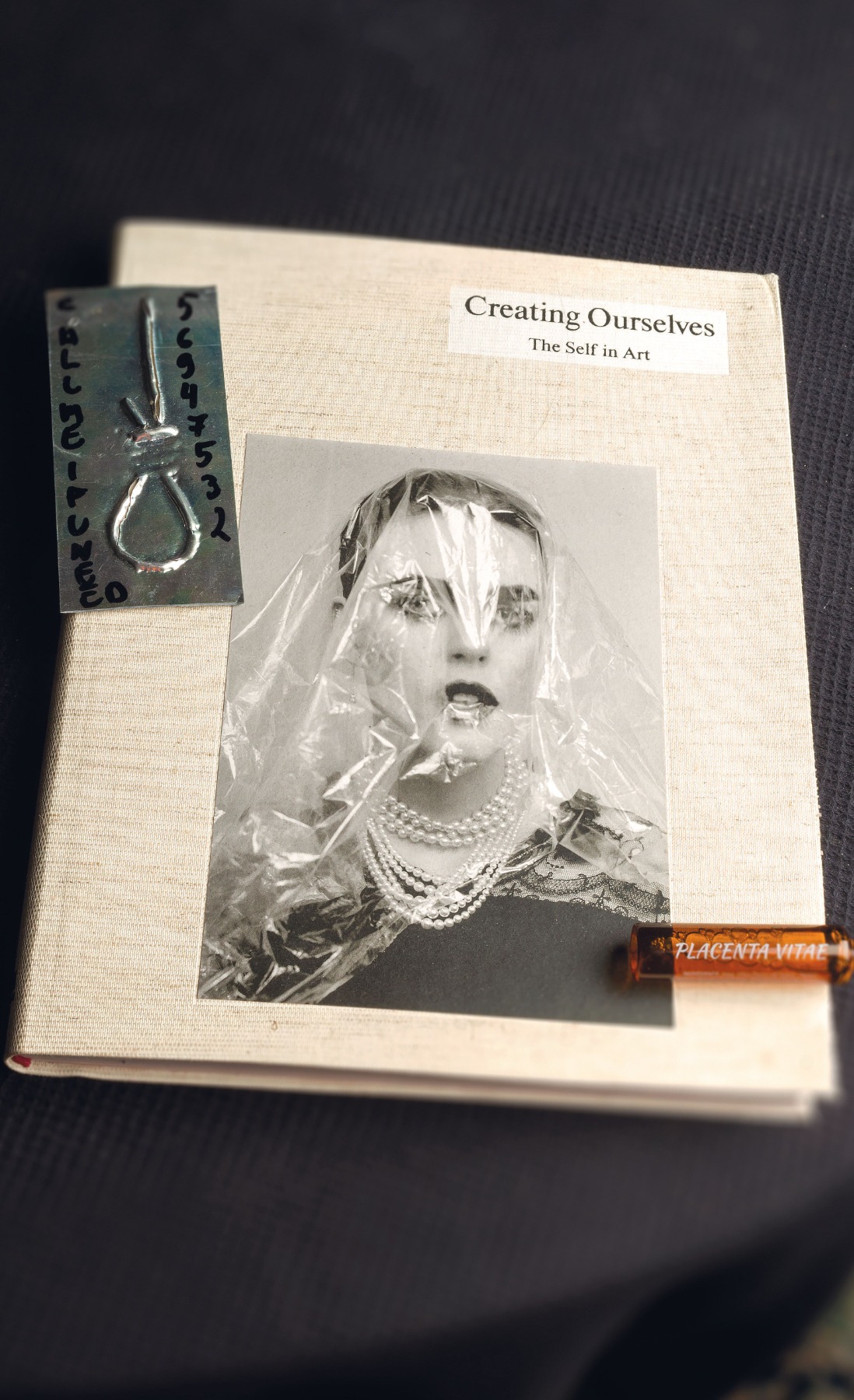

In a sense, creating a book about a collection is a similar endeavour. It is at the same time an entirety and a fragment. Impulsive, honed and emotional, it is an aesthetically saturated imprint of a certain point in time.

“What is random? Random is something for which you are not aware of the reason. But we are never aware of everything,” says Estonian jewellery artist Kadri Mälk. Hunt: Kadri Mälk’s Jewellery Collection (published by Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 400 pages), the long-nurtured book dedicated to her jewellery collection, was released in March, almost at the same time as the announcement of the coronavirus pandemic. It is a collector’s item in and of itself.

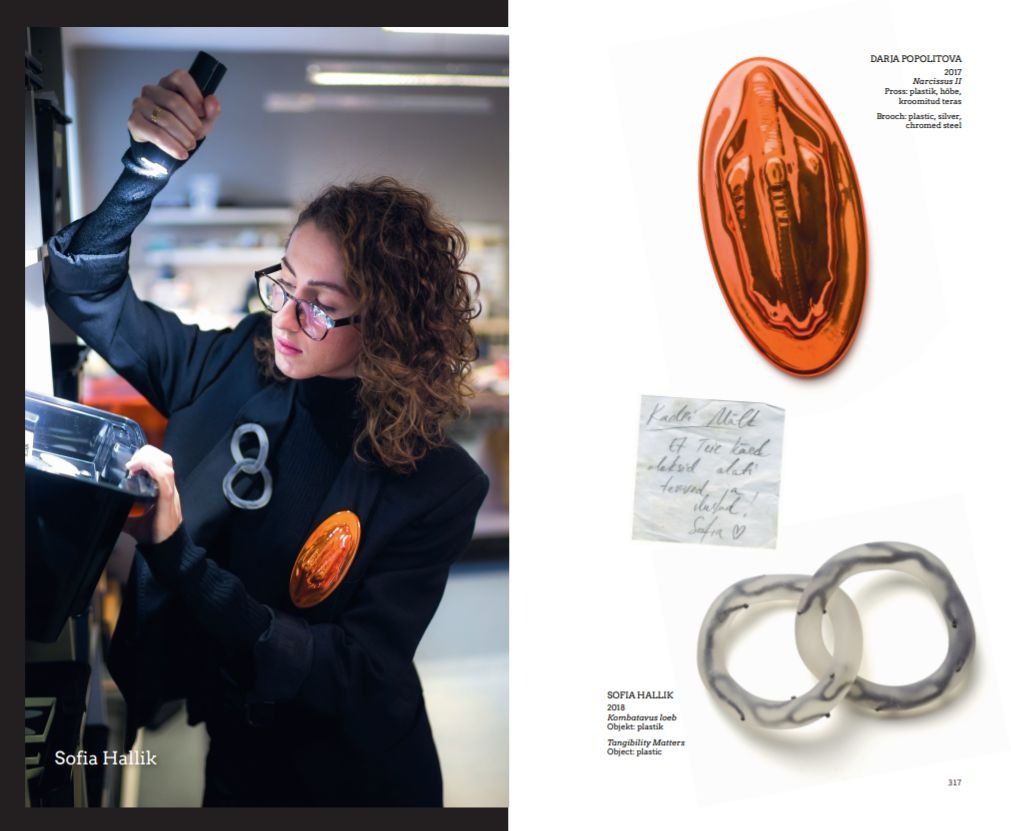

The book immortalises more than 100 people, who are photographed wearing some of the approximately 300 pieces of jewellery in the collection Mälk began amassing in the mid-1990s. Each of these people entered her life at one point or another and left an impression. Some of them became permanent fixtures in her life, others remained only as long as an image drawn in the sand. Among them are a three-year-old boy, a lawyer, a professor, a chef, fellow jewellery artists, collectors of Mälk’s own creations, a doctor, the chimney sweep who cleans the chimney in her house, the director of her country’s national art museum, and her own mother. I am also among them. At the same time, Mälk invited me to be a co-author of this book by contributing an essay dedicated to her collection, excerpts of which are included in this article. The Dutch freelance art historian, writer and curator Liesbeth den Besten likewise contributed a dedication to Mälk’s collection for the book.

Raoul Kurvitz wearing jewellery from the collection of Kadri Mälk

The photographs themselves also reflect a random process. The people in them were free to choose whichever piece of jewellery from the collection that they wished; their selections were spontaneous, based only on the feelings of the moment and earlier life choices that in turn influenced those unrehearsed feelings. In addition, it is not quite right to say that they are ‘wearing’ these pieces of jewellery; rather, the jewellery is in most cases like a partner in a spontaneous dialogue. Contrary to the conventional view that jewellery is mostly utilitarian, Mälk is convinced that jewellery can also be unwearable. “I think that the mere fact that the piece exists is already enough,” she says. “It’s important that it was created in the first place. You can use it even if you don’t wear it. You can just keep it near yourself, in your pocket, or in your mind. It’s a kind of metaphysical approach to the concept of wearing jewellery. You carry the jewellery around in your mind, and you know it’s there.”

Hilkka Hiiop wearing jewellery from the collection of Kadri Mälk

The idea of photographing the jewellery on people who have been important in her life is one that Mälk had for quite some time. “It’s about going deep. I tried to find the root reason for why I chose this or that particular piece and why this or that particular person appeared in my life. Like the man from Peru who runs a taverna just around the corner from here. Sometimes when I return from school, I go in there to eat something or just to sit down and rest and chat.”

I tried to find the root reason for why I chose this or that particular piece and why this or that particular person appeared in my life.

“...There are my friends, my colleagues, my doctors, my lawyers,” she continues. “The art historians who’ve been following my work, the man who cleans my chimney. Some people have left an impression on me because of their attitude or mentality or whatever. They don’t have to be very close to me every day. Like this small boy – I don’t meet him every day, but he’s still there and he sends me his drawings and so on.” In the book’s introduction she adds: “How have these people entered my life? Kairos! – if you let it pass, it’s all over. You have to recognise the right moment, the right time. Time doesn’t occupy the space between the hands of a clock. Time is the language of life and we sense it most powerfully in the context of bittersweet human experiences. And blood. Blood never sleeps. In short – the network of hearts around the world, as Tanel (Tanel Veenre, an Estonian jewellery designer and Kadri’s close friend – Ed.) says.”

On the one hand, this book provides an insight into Mälk’s jewellery collection. On the other hand, creating the book itself felt like a process of creative psychoanalysis. It became a story about jewellery and people, about interaction and impression. As German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer wrote in his Studies in Pessimism: “Why is it that, in spite of all the mirrors in the world, no one really knows what he looks like?”

There was once a brothel on the first floor of the house where Mälk lives; from her bedroom window she can see a church. Ever since the first time I met her, several years ago, I’ve felt like there’s something shamanistic in her jewellery...and in Mälk herself. In her coal-black hair, in her black clothing, in her voice, which seems so familiar even when heard for the very first time. Mälk’s jewellery bears some similarity to ritual objects and the mystical communicators between our world and the world beyond some border. Her creations have a melancholic poeticism, and in one sense they are the spiritual essence in which the energy of the artist’s materials meets the energy of her own being at that precise moment.

I remember Mälk once showed me a small piece of mole fur that she had used in several of her pieces of jewellery. “It’s a very old story,” she said. “My studio was broken into, and soon after that, as I was rearranging some belongings, I found my grandmother’s fur coat. It had been made before the war, but it was so fine, so delicate, such a saturated shade of black – almost like silk. And it had lots of character. A mole is blind, but it’s nevertheless a very special animal – I’ve studied its movements a lot. It moves just as nimbly forwards as it does backwards. It has a very powerful animalistic instinct, and I still feel that in its fur. Time does not lessen its quality or sheen. And so I’ve been cutting up this fur, little piece by little piece, for more than 20 years already, and it’s been scattered all across the world through my jewellery.”

With her art collection, however, Mälk has been doing exactly the opposite, namely, uniting all of these objects (that is, pieces of jewellery) that have been scattered around the world and bringing them together in the context of her own life and vision. She describes her approach to collecting like a participle conjoining Kafka with Mowgli. “The Kafka side is this person who outwardly seems quite ordinary, who goes to work at eight in the morning and returns home at five in the afternoon. This humble approach. But for Mowgli, it’s wilderness. I’m trying to not be like a professor when choosing the pieces. I try to be as if blind, with closed eyes. It’s this kind of innocent way of looking. I’m not searching; I’m finding. I can really make a decision in a moment. I immediately see when something is mine. There’s some kind of magnetism between me and the piece.”

Unlike many other collections, Mälk’s is significant for not having an immediately apparent focus or conceptual guidelines. It ignores trends and status pyramids. It’s as free as a bird diving in the air. And its only constraint (apart from the material aspect) is the boundaries, corners and edges marked by the twists and turns that Mälk’s own life has taken. Her collection contains work by her present and former students, internationally well-known artists, relatively unknown artists, creations by absolute amateurs and also ethnic jewellery from the 1920s, 1930s and 1950s from such exotic places as Burkina Faso and Mali. The only conditionally unifying aesthetic aspect to her collection is the colour black. Simply because it is her colour. “Black is the queen of colours. I can’t explain it.” But even the black is not absolute.

The manner in which Mälk collects is both random and deliberate. In essence, her collection is a deliberate practice of randomness. It’s her personal memory, a diary written in the language of jewellery, a diary which at the same time forms a part of collective memory. At what point does something become a collection, and is a collection something more than just a group of things? “It’s much more,” says Mälk. “It’s not just grabbing things together, like a person might have many different glasses or sets. When I invite 20 people for dinner, I never have a set of 20 plates all the same size; they’re all different. So it’s not like grabbing things together; it’s a spiritual kind of act.”

The manner in which Mälk collects is both random and deliberate. In essence, her collection is a deliberate practice of randomness.

Mälk has also had some very heated discussions with her husband about the collection. “He called it like a dead museum. I wear the jewellery from time to time, although not all of the pieces. I never wear my own pieces. Never, ever. But he always says that I just keep buying one safe after the other, and what’ll happen after that? I usually answer that, as a literary scholar, he also doesn’t translate everything that comes his way; he only translates Kafka, Günter Grass, the best of Swedish, Dutch and Greek literature. So how can he not understand that the same can happen in the field of jewellery as well? That you simply feel. How can you feel that a novel or a poem is worth translating or reading? He doesn’t understand. He says, ‘Make what you’re good at. Make jewellery. Don’t pretend to be somebody’s expert or collector.’ But I don’t pretend. I’m not educated as a collector. In this sense I’m wild.”

Mälk began collecting spontaneously as well. She had originally studied painting but soon realised that this was not her true medium, both in the sense of dimensions and physical sensation. “Jewellery is more intimate, closer to the soul,” she says. However, she admits that in her case, the spontaneity is probably only a facade. As her family tree shows, the collector gene can be traced back to her ancestors and was probably just waiting for the right, fertile soil in which to take root. Mälk’s grandmother was an embroiderer and owned a collection of jewellery; Mälk’s mother also inherited this inclination and collected jewellery made by Estonian artists. “So, in this sense, it was in my blood, but I didn’t consciously cultivate this pursuit until I started to study jewellery myself. I bought my first pieces just randomly, and then after that I did it already consciously.”

“Excellence is never an accident. It is always the result of high intention, sincere effort and intelligent execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives – choice, not chance, determines your destiny,” wrote Aristotle. If we compare Mälk’s collection to a boat, in addition to professional navigational instruments and many nautical miles traversed, it is also equipped with a brilliant ability to “feel the waves” and has no fear of experiencing the full range of what the water (and life) has to offer. In a way, her collection is a work of art in and of itself, full of vivid episodes in miniature. Each piece of jewellery in it has a story that far exceeds its physical and aesthetic boundaries.

“It’s a complex combination of energies, created by the stone itself, the designer who has worked with it, and the person in whose hands the jewellery ultimately arrives,” Mälk once said to me when I asked whether, once a piece of jewellery is finished, she had added her own energy to the energy of the stone.

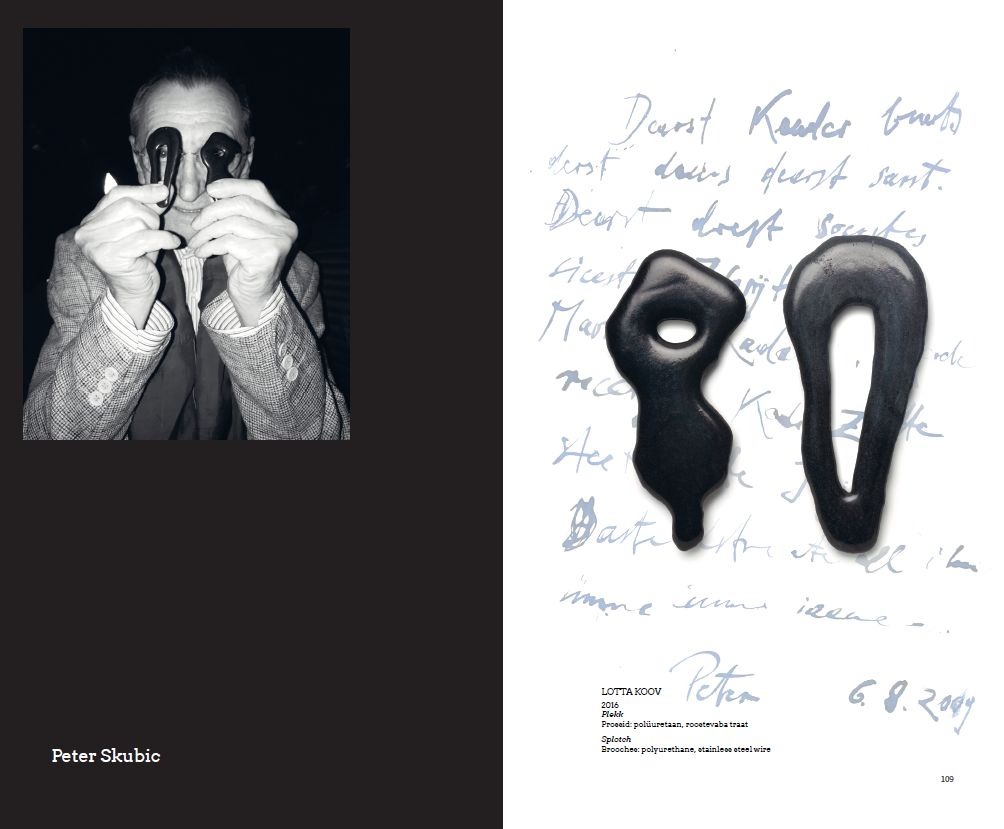

Although Mälk’s collection also contains some jewellery made in small series, most of the pieces are unique. The paths by which they have arrived in her hands are as diverse as life itself. For example, legendary Swiss designer of conceptual jewellery Otto Künzli recently gave her a pendant from his iconic Blape collection. Some of the jewellery was made especially for Mälk, and these are true gems of creativity. Swiss designer Adam Grinovich made his only black piece of jewellery for Mälk; all of his other work is white. Mälk also has a piece in her collection made especially for her by Austrian designer and artist Peter Skubic, a provocateur, intellectual and free thinker whose work can be seen in many museum collections, including MoMA and MAD in New York City.

It’s a complex combination of energies, created by the stone itself, the designer who has worked with it, and the person in whose hands the jewellery ultimately arrives.

Many of the pieces in the collection have also been made by Mälk’s own students. When I ask whether this is a way in which she can show her support for them, she says: “Many people put it this way, but actually no. Of course, some of the pieces have been given to me as gifts, but many of them I’ve bought. For example, I have in my collection three pieces by Estonian artist Urmas Lüüs. When he graduated, he gave me one of the first pieces from his ‘heart’ series, along with a very nice letter that said, ‘Thank you for your unconditional support in all circumstances.’ The heart is black, of course. Later I bought his pendant that was shot with gun; you can even see that there’s still smoke. The third piece is very personal. He had a family drama at that time – his boyfriend left him and he broke all the plates he could find at home, and then afterwards he made jewellery.”

But Mälk also has jewellery in her collection whose creators she has never personally met, life nevertheless having brought them together indirectly. For example, Dutch designer Onno Boekhoudt. Mälk has his Flower ring, made of silver wire and with a diamond on top. “You bend it around your finger according to its size. You can bend it very loose, so the whole finger is covered with the wire, or you can bend it in a very dense, compact way. It’s so nicely done. I never met Onno Boekhoudt personally (he died in accident), but I had met many people who studied with him, and so I really appreciate his conceptual and philosophical approach to jewellery. He was very focused on process. The final piece was not so important for him as the process itself.”

Just as in life, a collection also has its missed opportunities. Pieces of jewellery that live only in the mind and memory. “You asked whether there’s anything I regret not having bought. A good friend of mine was Manfred Bischoff; we participated in several exhibitions together. He had that ‘gold potato’ (Pomme de Terre–Pathètique–Tragique, 2002) with black corals that somewhat perversely looked like mouse droppings. His pieces of jewellery were miniature sculptures, full of humour and references to various classics. We talked about them a lot, but they always seemed expensive to me. Still, because I definitely wanted at least one piece of his, I said I would figure something out and maybe he could put a piece aside for me. But then he died unexpectedly, in 2015 in Italy. And so I don’t have any of his jewellery. His heirs later fought over his estate, and so I had no chance at all. We were very close, but I didn’t make a decision at the right time. That’s one of my life lessons: you always have to catch the right moment, otherwise it’s gone.”

Italian artist Gianni Motti has a work called Success Failure (2014) – a pole with two signs, each pointing the opposite way, a humorous commentary on the myths and obsessions of our 21st-century social order. The same could be applied to collecting – is it even possible to make a mistake when collecting? And who has the authority to evaluate these apparent mistakes or successes? Especially considering that the only true assessor is time itself. And time’s assessment often has little to do with the opinions of supposed experts at the time when a collection is formed.

With a smile, Mälk pulls out a small, velvet box that holds a pair of earrings made by legendary American costume jewellery designer and Hollywood darling Kenneth Jay Lane. “I thought I would afford myself something really high-end. I didn’t know him personally, and I ordered these earrings on the internet. I really spent a lot of money, and a couple of weeks after I received them in this very refined box, he died. He died in his New York apartment. He was living with a leopard. You know, this big cat. I don’t know what happened, but shortly after that the prices for his jewellery suddenly shot up extremely high. I was lucky to have bought a piece just two weeks before his death. It’s kind of exceptional. Of course, it’s a serial piece, it’s not unique, but it’s exotic. I thought I should have one piece by him.”

There are some pieces of jewellery Mälk has never removed from the safe. She bought them at moments of weakness. “I was at the seashore, there was a sea museum and I bought some amateur pieces. It was kind of an emotional decision. Physically, they’re part of my collection, but they’re not the core of it. They’re not professionals, just people who lived in the neighbourhood, mainly fishermen’s families. It was like a postcard. They always recall this place on the seashore.”

Is it possible to get an overview of what is currently happening in the niche of contemporary jewellery by looking at Mälk’s collection? Probably not. But that’s not the goal of the collection. “It’s just a vibration. The moments are here, in my heart. For example, I’ve never met Slovakian designer Lucia Babjakova. I’ve just seen her work somewhere. But I have two pieces by her. One is wearable, and I also wear it on my back. There’s this chaotic movement to the piece. This kind of sensitivity, the dynamic of the moment. Like a life.”

Mälk’s collection is literally a living organism. It has the “flesh and blood” of emotions and experience. The “seventh plane” of choice that does not respond to rationality. Plus a childlike curiosity unpolluted by layers of life experience. “I am not spoiled by these 60 years that I’ve been living on this Earth. I admire and I get really excited. My admiration is like...I can’t sleep when I’ve seen something really impressive. Normally, a sixty-year-old woman maybe doesn’t act like that.”