Ene-Liis Semper, Contemporary Buddhist

24/10/2011

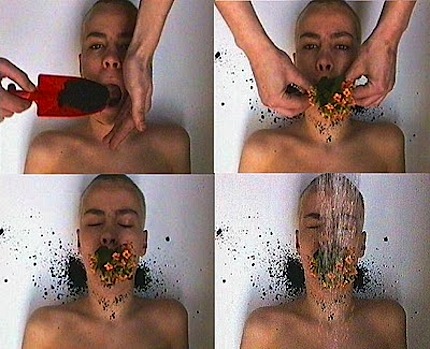

Ene-Liis Semper (1969) is an Estonian artist who works with contemporary video and performance art. Educated as a stage designer, she has spent most of the last ten years actively working at the local theater group, no99, which she heads together with with her life partner, the director Tiit Ojasoo (1977); their performances have been acclaimed by both local and international audiences. Semper currently has a solo show (since 14 October) at the KUMU art museum in Tallinn. This is quite an event for appreciators of Baltic art, considering that the artist hasn't had a solo showing since the already-distant 2006. The exhibition at KUMU will last until 21 December and demonstrates that the museum's expansive fifth floor can be changed beyond recognition.

After meeting with Ene-Liis Semper, two things become clear. Firstly, the artist's creative works have transformed into a contemporary amalgamation in which the line between stage design and visual art has become blurred. Secondly, one comes to the realization that both existential angst and an unfeigned joy of living can exist very close to each other, for Semper's soul lies on the border between the two. This state can be obviously seen in the no99 theater company's tradition of labeling each show with a numerically decreasing number. Their first project was no99, and on 26 October, they will be opening show no67, “Appi, tulmukad!” One day, it will be zero's turn, much the same as it will eventually happen to all of us. “Being cognizant of the horizon mobilizes people, while disillusionment about an infinite future makes them careless,” says Semper. Quite like a contemporary Buddhist.

From the video “Oasis”. 1999

You work in the theater as an artistic director, as well as pursue a career in contemporary art. Do you see yourself differently in each of these roles, or are there parallels that can be drawn between the two?

In my first period of actively working with video art – at the beginning of this century – my approach was different. At the time, I was working in theater just as a stage designer, but in video art, I could be independent and carry out anything that came to mind. Ever since Tiit Ojasoo and I established the theater, no99, where I could freely experiment, I found that my background in the fine arts helped me with my stage work, and vice versa. For instance, in 2009 we performed the play “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” [it will be performed in English on 3 October at no99, as part of the “Tallinn – European Capital of Culture 2011” program]. We took the name from a famous 1965 performance by Joseph Beuys (Germany, 1921-1986). It's like a commentary about the relationship between the artist and the viewer, also between society and art as a whole. The show was my idea and I was also deeply involved in the direction of it. We improvised more on the stage than we usually do.

We are continually integrating different approaches to the creative process. Our inspiration can be modern dance, contemporary art, music, installations or performances. Several levels are possible in one show. Space and its design are beginning to take on great meaning in my art; in my solo show at KUMU, the viewer is “guided” as through a labyrinth. In my opinion, the melding of both fields is an undeniable benefit.

Do you still use your body as the central character in your video works?

Yes and no. I'm still visible in some of the new videos, but the show also contains three works in which I used actors.

Why so?

To increasingly distance myself. At the moment, I'm specifically interested in emotions; to attain an abstract level in art. To remove the world of emotions from the conventional context. In a theater production or a film, for instance, emotions are part of the narrative; but in art, I try to pull them away and highlight them separately. And the actors are from my theater troupe – I trust them. I knew that it would be easy to work with them. >>

Marina Abramović – the “Grandmother of Performance Art”, as she has christened herself – once said that for creativity, the most important part is the “space in-between”, meaning the psychological state where we haven't yet come to a safe place where we feel at home, but we are on the way there. Abramović believes that we are at our most vulnerable when in this “space in-between”. And that specifically, vulnerability is the fundamental condition for our minds to be open, so that we can truly be creative. Do you agree? Specifically, in terms of vulnerability?

Absolutely. In the last eight years, we've used a similar ideology in the theater. Our condition is that we never repeat ourselves, that we don't copy ourselves; we must always go forward and challenge with something new. I'd like to emphasize that no99 is not a typical theater, it could even be seen as a conceptual art project. For instance, we just closed down the Straw Theater, which was open in Tallinn all summer long. It started out as my idea of a huge installation in the urban environment, but it outgrew that and became a work of art with a functional role – it became an activity space for city dwellers, as well as a cultural center where we exhibited and performed different international projects that we had seen around the world and wanted Tallinners to see for themselves. The Straw Theater expanded into something like a big performance.

In such an “unsafe” position – invading unknown, as of yet strange horizons – we relentlessly try to support both ourselves and the viewer – we also want the viewer to become braver and to leave his or her comfort zone. To carry this out, we begin with the method of how we work with our actors – we don't give them a script before rehearsals because often, an already memorized script protects the actors. In its place, we use improvisation, as well as long discussions about the intended situation in the plot and how the actor should express himself; after which, we rehearse again. It is possible to find similar theater troupes in the world that work at such an intense level, but it's not typical of theaters that have national importance. Yes, we are a state theater! We replaced a theater that went bankrupt and created a new team, all the way from the directors to the stage lighters.

What sort of advice would you like to give to viewers of your newly-opened show, or rather – what sort of message would you like to send out?

The space at KUMU, namely, the fifth floor, or as it's otherwise known, the Contemporary Art Gallery, is really huge. That's why the curator [Eha Komissarov] suggested that we include some earlier works – videos in which I'm still the central character. As a result, the exhibition allows the viewer to follow how my viewpoint has changed over the years.

Are there any artists that inspire you, whose works you can always return to and they never disappoint? Or has there been an exhibition that left you with a strong impression?

Truth be told, I've spent the last three or four years looking for good, new works of art. But it's a strange period right now, because there are only retrospectives going on all over the place. However, two years ago I was really delighted by a show in Berlin – by the American artist, Bruce Nauman (1941)... but that was also a retrospective! (Laughs) The exhibition was so powerful and so full of energy that I was taken over by sadness – all of the best works have already been made in the 1960's and 70's. In today's art scene, I'm missing this clean image – a work that's not just a commentary about something else, but that brings about a flight of imagination, free of associations. Today, there's a whole row of works that are associated with different discourses that I just can't follow anymore. As a human being, I miss the opportunity to connect with unforced, simple and clean art.

Will this situation in the art world change?

I don't know, I'm not sure; if I knew how to change it, I already would have done it. (Laughs) But – hopefully. Yes, hopefully.

...There are so many stories about the theater, but my art and my work with theater productions have grown together so very much. In addition, I'm confident that a certain level of abstractness can be attained on the stage, not just in art galleries. In the actors' portrayals, we accent the person's presence – not so much the verbal message and narrative. Emphasis is put on rhythm, energy, the show's dynamics, the relationships between the characters. It's like a step ahead – contemporary theater.

But what do you mean by the word “contemporary”?

A bit more freedom in mixing together different mediums, but not in an illustrative way. If you have the capability, then you can successfully and elastically combine, let's say, an installation and play acting. And you can do it so that the consolidation seems natural, even necessary for the content. Being contemporary is my belief in the future.

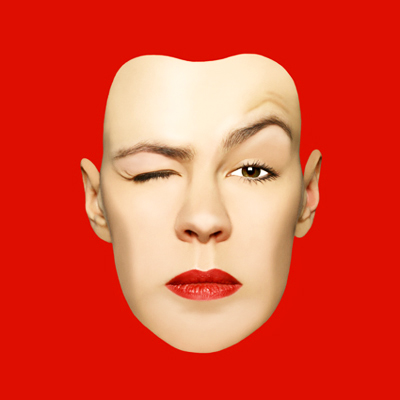

Ene-Liis Semper. Portrait made by estonian artist Laura Kallasvee