“Art can help to save us from self-destruction”

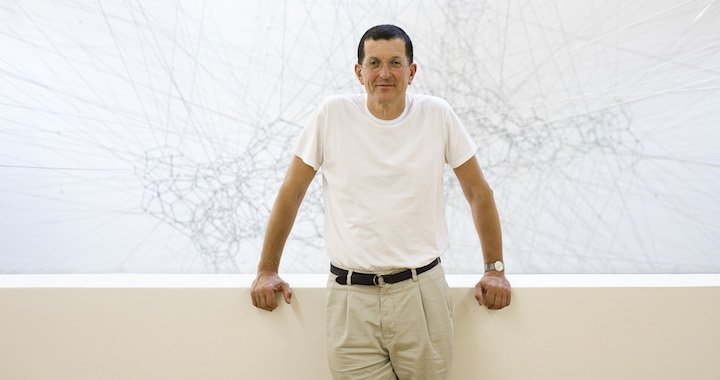

An interview with British artist Antony Gormley

03/10/2014

Material produced with the support of ABLV Charitable Foundation

Material produced with the support of ABLV Charitable Foundation

“Everything is possible, nothing is impossible,” gallerist Stefan Andersson tells me speaking of the British artist Antony Gormley. Galleri Andersson/Sandström, the Stockholm art gallery co-owned by Andersson, is currently hosting a show of Gormley’s latest pieces entitled MEET, running through 4 October 2014. “The show is extremely important to the art scene in Stockholm; it is fantastic that we have got the possibility to show one of the absolutely most important artists in the world here in Stockholm. We are very proud,” admits Andersson who is acquainted with the artist since 1994 when Gormley contributed to the Umedalen Skulptur exhibition of outdoor sculpture in Umeå. “Still Running”, the piece created by Gormley for the show back then, is still on view at the sculpture park in Umeå owned by the Balticgruppen real estate company.

Antony Gormley. Still Running. 1994. Umeå, Sweden

The MEET exhibition is a significant event on the Stockholm art scene although, apart from a local freelance journalist, I am the only one to show up for the press tour personally guided by Antony Gormley. And yet the official opening later on the same day sees the gallery jam-packed with people. The vernissage coincides with the launch of the new Stockholm art season, and the cluster of galleries in the Hudiksvallsgatan neighbourhood is reminiscent of a giant ant hill.

Antony Gormley is sometimes called a philosopher of the body: he uses his sculptures to ask questions routinely pondered by the minds of philosophers, for instance, the body / mind problem or relationships between man, nature and the Cosmos. The difference lies in the fact that a viewer of a work of art has the option of experiencing the answers quite personally instead of looking for them through theoretical reflection. The artist has always emphasised experience and feelings as more important than just a rational and knowledge-based approach to the interpretation of an artwork. Gormley’s sculptures remind us that there is an “inner space” in all of us, some sort of dark depths – not just locking up our thoughts and feelings with the help of our consciousness; rather, it is a place hiding an infinite expanse worth exploring. Undeniably, a great role in Gormley’s development as an artist was played by the number of years that he spent in India embracing Vipassana-meditation. And yet, as Gormley later pointed out in the interview, everything that he learnt there had only confirmed things that he had intuitively realised as a child. In any case, it is an inexhaustible source of nourishment for his art.

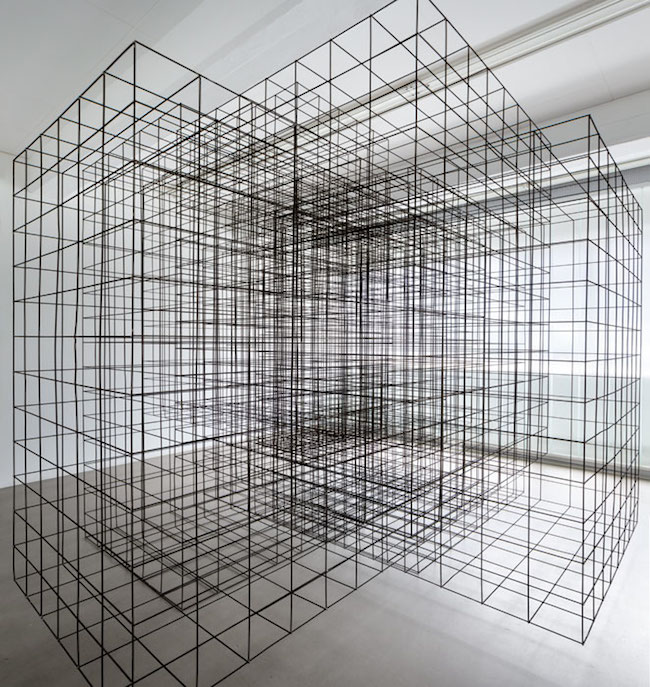

Antony Gormley. Exhibition view. MEET. Galleri Andersson / Sandström in Stockholm. 2014. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Bérange

Winner of the Turner Prize (1994), the top British contemporary art award, Antony Gormley has been working in contemporary art for more than three decades now. 2013 saw him receive the special Praemium Imperiale Award, presented annually by the Japan Art Association to prominent art figures worldwide. Alongside the sculptor Antony Gormley, other 2013 recipients included Francis Ford Coppola (theatre/film), Plácido Domingo (music), Michelangelo Pistoletto (painting) and architect David Chipperfield whose practice, incidentally, designed Gormley’s London studio in 2003.

In 2011, a maquette of the “Angel of the North”, Antony Gormley’s most recognisable outdoor sculpture was sold at a Christie’s auction in London at record-breaking 3.4 million GBP. The actual sculpture – 20-metre tall with a wing-span of 54 metres – can be viewed towering over a road near Gateshead. The artist often chooses to create sculptures for landscapes or urban environment, venturing outside the walls of art galleries and museums to be closer to people. Incidentally, Gormley’s sculptures are often cast in a mould taken from his own body – which involves motionless waiting for hours until the mould hardens. It also means a constant battle with his own fears: the artist suffers from claustrophobia.

Antony Gormley. Room. 2014. Photo: Stephen White, London. © Antony Gormley

“Antony Gormley’s £2,500 “Room” without a View” – it’s the title of an article in The Guardian dealing with one of the artist’s latest works, a special room for the Beaumont Hotel due to open this autumn in London. Clearly noticeable from outside, it is sitting on top of one of the building’s wings like a Cubist steel man; hiding inside, there is a velvety dark and quiet luxury apartment – “The Room”. An opportunity to isolate oneself from the hustle and bustle of the modern life is what Gormley considers the greatest genuine luxury of our time.

Since September, 60 of Antony Gormley’s sculptures – each featuring a figure in a different position – electrify one of the exhibition halls at the Paul Klee Zentrum in Bern with their silent presence. “Expansion Field” is running there through 14 January 2015.

Antony Gormley. Havmann. 1994. Granite. 1001 x 300 x 109 cm. Mo i Rana, Norway. © Antony Gormley

Why do you keep returning to Scandinavia?

I have a bloodline myth that the ‘Gorm’ in ‘Gormley’ actually comes from a Viking; a king of Denmark, who was also the father of Harald the first Christian king. Anyway, there is no doubt that my tribe comes from up here – although we are talking about a time a thousand years ago. So I feel a kind of sympathy with the North. There are attitudes to nature in the imagination ofall Scandinavians that I find very compelling, combined with a kind of anxiousness; “Will our darkness ever be relieved by light…” a melancholy that I identify with also.

Over the years, I’ve found here an incredible support and opportunities. The first serious museum show I had was at the Louisiana in 1989, then in Malmö in 1993, and so on. And there are also opportunities to do big projects here, like the Holocaust memorial in Oslo (2000); Another Place in Stavanger (1997), Havmann (1994) or working with Claes Nordenhake in Stockholm in the 90’s and then Stefan [Stefan Andersson, the founder and co-owner of Galleri Andersson/Sandström – A.I.] up in Umeå.So, yes, I do keep coming back.

Antony Gormley. Another Place. 1997. Cast iron. 100 elements: each 189 x 53 x 29 cm. Stavanger, Norway. © Antony Gormley

It’s difficult to put one’s finger on it completely, but I think there is a connection here with Japan. In Japan you get a sense of the way in which Shinto attitudes to the elemental co-exist with an industrial or post-industrial society. You feel that here too. Yes, Scandinavians are very happy to play the game of a modern liberal democracy of an industrialized, socialized nation, but if they didn’t have their sauna or they couldn’t go into forest, things would not be ok anymore. And I have sympathy with that.

When working on your MEET show,did you find an answer to the proposed question – why do people with infinite inner space want to create these artificial boundaries like houses, cities etc. Why is that so?

There is no answer other than this – human beings are very, very frightened of the fact that Space is infinite and ever expanding. We want to protect ourselves against that, because it is fundamentally frightening; it tells us how totally provisional we are.

Although the human species has never been bigger in population than today, at the same time we are contracting in terms of population concentration. We are contracting into highly artificial habitats that are increasingly high-rise and high-density. So to answer the question “what is the human nature within nature at large?”, we have to talk about a new form of nature; you could call it meta-nature – something that comes to us second-hand, through virtual means. We withdraw into a hermeneutic space: technology has taken us away from the first-hand experience and direct action.

As we withdraw in this highly defensive and highly technological habitat, the effect on the bigger system: the lower depths of the oceans and the upper atmosphereis more and more profound. We are very aware of that now. The unpredictability of our weather patterns and the absolute destabilization in the elemental world are directly linked to this artificial withdrawal into the technological high-density habitats of the human.

We have externalized our evolution into our immediate environment, and yet we have not evolved ourselves in terms of consciousness. So there is an imbalance. The necessity for a cultural shift to avoid becoming auto-destructive – is great. Art could have a role in this.

Antony Gormley. Exhibition view. MEET. Galleri Andersson / Sandström in Stockholm. 2014. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Bérange

It’s also what you talked about in your essay “Art In The Time of Global Warming” (2010), where you state that art is unnecessary but vital. But at the same time artists as well are part of this production of new things…

Yes, we are both the reflector of and the symptom of a mass consumption society. (Laughs) I am very aware of this. I have to admit that I provide objects for the luxury exchange market.

But you still believe that art can save as from self-destruction?

I believe it can help, though I have a big problem with the instrumentalization of art, when it becomes a tool for urban regeneration. Art is a catalyst of reflexivity. One of the ambitions for an artist is this: if you can concentrate your efforts, physical and intellectual, on an object so that it becomes in a way resolved adequately and finds a space where its resolution can resonate and so that it will cause other people to be able to concentrate.

For me, the big artistic evolution is the shift from representation or art that just re-affirms things that already exist and an art that allows us to look at them again in a reflexive way. Much current art, particularly from America, is part of the mass consumption culture and overproduction. I think that art has a bigger job to do.

Art can shift our thought and feeling patterns in a new direction. There has to be some disequilibrium in the art experience, some deliberate strategiesof disorientation for the viewer.

Do you care where your artworks end up – to whom they belong and who sees them?

I used to terribly… until I realized that I just have to be thankful that somebody is prepared to give them a home.

But what worried you before?

What worried me before was that the work was going to end up compromised or incapable of functioning because it was going to be contextualized in a way where it wouldn’t work at all or even would look ridiculous. And I think that became almost a paranoia for me. Because it is one thing to make the work and another to make sure that the work is properly installed and that it works. At the beginning I even invented a complicated contract of sale, which meant that the collector had to agree with me about where the work was going to be placed, how it was going to be lit, and what its conservation and future care was going to consist of.

Did someone really agree to all these clauses?

I’m not sure that anybody did! (Laughs) I spent a lot of time drawing this document up. After I showed my work at the Venice Biennale in 1981, two absolutely charming New York art collectors beat their way to my door, which was at that time an old chicken shed in the countryside to the north of London. They were interested in my work. I showed this document to the wife of the collector and she just said: “Oh, Antony, you really just don’t understand. You want to sell it or you don’t want to sell it?! If you want to sell it – just let it go!” It was an early lesson and I think a good one. We just have to be thankful to have another chance to make another work.

Antony Gormley. Exhibition view. MEET. Galleri Andersson / Sandström in Stockholm. 2014. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Bérange

At the same time, a lot of your works are in public space where they are quite unprotected from bad weather or creative hooligans. But it seems that you even like it.

I would like to think that I am a creative hooligan myself. (Laughs)

But, yes, isn’t that a great thing. As an artist, I grew up waiting for the benediction of the aesthetic popes of the art world, hoping they might recognize my contribution. But then I realized that was an unnecessary stage. One of the things that sculpture has is its ability to endure. It doesn’t need a wall; it doesn’t need a shelter or the intellectual protection of an institution. You can put things on the street; you can put them on the beach, in the mountains or in a playground. And in doing that you make a direct dialogue with the world, and that’s incredibly exciting. I did come to this realisation instinctively; from making holes in sand castles on the beach to putting my artworks on the beach, it was an organic development.. It was liberating for me to say that I don’t need the validation of these so-called art experts. The sculpture can work in unprotected places and make connections with unsuspecting public which need not have any prior knowledge or experience of art.

From the very beginning, that has been an important part of my experimentation – with how art might work, who it might be for and – indeed – how it could be made. For example, all the Field projects are collectively made and occupy collective space – old factories, old supermarkets etc. In ancient times, Neolithic farmers made these extraordinary imaginative spaces, these standing stone circles. This was a collective act of creating spaces that helped put human beings in a wider Cosmological context. I still get huge inspiration from that. And I guess I also get inspiration from American artists of the late 60s and early 70s who also were inspired by that. For example, Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977) and also Robert Smithson’s or Michael Heizer’s projects. They seemed to realize that we can do things directly with the earth, with the topography of the landscape – totally outside of this idea of consumerist culture that wants to commodify everything. I guess I fund one with the other. That’s my game.

Antony Gormley. Still Standing. 2011–2012. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia. Photo: Yuri Molodkovets. © Antony Gormley

Two years ago at the Hermitage you took the ancient sculptures and put them directly on the ground. What was your idea?

It was democratization of God. Let’s recognise that these sculptures are human-made objects. We may call them Dionysus, Apollo or Venus, but let’s put them on the same plane as the viewer., Let’s put the viewer in the position of the sculptors who made them, in order to recognise that these are imagined projections. This was a really important and amazing opportunity to look again at the idealisation of ancient sculpture, to treat them as things in the world – as found objects, and allow them to be released from the tyranny of the plinth.

There were 27 objects, most of them on plinths and against the wall. I removed 23 of them from the room, kept four, put them on the floor and raised the floor level, so it was equivalent to the sculpted ground. In that way we lost most of the integral marble bases into the floor. We dropped the sculptures and we raised the public. This was a way of asking: what is sculpture now, what can sculpture be and can we re-examine the inherited culture? There is a fixation with the classical Greek statuary and the Roman copies; in many people’s minds they are still the idiom of the body in sculpture. But let’s take this whiteness, smoothness, nakedness and this idea of perfection and look at that again to see that most of these works have been repaired several times, some of them even are constructs, made from many different works that are put together and have new noses, arms and legs. I invited viewers to recognize that these ‘ancient’ sculptures were a collage, a constructed notion of purity.

Speaking of your own history – what motivated the 21-year-old Gormley to go to India and meditate there for a few years?

I was lost and I wanted to find myself. I was a hippie and I wanted to do what other hippies did. I went to India for the first time in 1969. But I was not alone; there were magic buses leaving every week from Victoria station to Kathmandu. (Laughs) So it wasn’t an original idea. And it took me a long time to get there because of the India-Pakistan war, so I spent a year messing around the Muslim countries – Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan. But I think that it was a good pre-education before arriving in India.

I was lucky to meet a good teacher, Goenka. It was a great experience: learning Vipassana and understanding that consciousness was not simply about the uses to which it can be put to achieve preordained tasks but that consciousness was an infinitely subtle process. That intelligence wasn’t to be measured by the amount of facts that you can remember from the books but that it was about tuning in the experience itself and experience of being. Just stopping and sitting for long periods of time and just being aware of the rising of thought and detaching yourself from that process, not identifying with your thoughts. Or watching a feeling arise and saying – that is a feeling, but I’m not going to call it mine. It was a very useful technique.

Before arriving in India, I had finished my studies at the university where I had a very classical education in which everything was about re-combining or making structures out of other people’s thoughts. But these profoundly subjective experiences in India were more powerful to me as indicators of how I might live in a more aware way. Yes, these were revolutionary thoughts for me.

You had a chance to stay in India, but you decided to return to London and to become an artist.

Yeah, I could have stayed there forever. (Laughs) But it seemed a bit like a betrayal.Had I been born in a family in India, that would have been a natural thing. But I suppose I felt that it is not that easy for me. And I guess I wanted to test the weight or the value of the experiences I had with Vipassana in the context of my nurture, my upbringing. Basically I had to choose: do I take the Buddhist path and wear robes permanently, or do I pursue the talent, the love that I have for making things, for drawing and painting.

Could it be said that your fascination with the body started in India?

Probably. But I think that the truth is – what I learned in India really just confirmed the intuitions that I had as a child. The mind/body theme for me started during the enforced rests in early childhood when I was sent upstairs to have a rest after lunch, which is the last thing that a young kid wants to do. I must add that I was brought up in a very religious house, in a Catholic family; we had prayers before breakfast and prayers before bed. And I did what I was told.

So this experience of lying in a brightly lit room on a summer day and not moving, being in this very tight claustrophobic space, with red light coming through my eyelids – I felt incredibly bound, but at the same time the space behind the closed eyes became cooler and larger. So the notion of expanding body consciousness was implanted in me already in childhood. And I reconnected to that when I was in India and pursued a more disciplined exploration. Vipassana means bare attention to Vedana or bodily sensations – to the field of body zones as a non-measurable topography, because there is always an infinite degrees of detail and you will never get to the end of it.

Anyway, those experiences completely informed all of the later work and are still completely intrinsic to this show.

Antony Gormley. Blind Light. 2007. 320 x 978.5 x 856.5 cm. Commissioned by the Hayward Gallery, London. Installation view, Hayward Gallery, London. Photo: Stephen White, London. © Antony Gormley

Speaking of expanding – you have worked with the body, you have worked with architectural structures and also in the field of architecture, you’ve played with the horizon. Could it be said that Blind Light (2007) was the most radical step where you invited the visitor to completely “lose” the body?

Yes, Room is a new hotel room in London which is trying to achieve the same with darkness. I’ve been frightened in a way of building the experience of darkness. I didn’t know how to do that. But at the same time I think that the relationship between the known exterior and the unknown interior in this project is so strange and extreme that the tension between the two is very strong.

I am aware that I’m torn in two very opposite directions: I would like to work with light or air itself as my primary material; at the same time, I am very attracted to the most archaic aspects of sculpture. A standing stone represents for me a marker in time and space against which we measure ourselves who are immersed in biological time while here is this stone which belongs to planetary time. As a child I was brought to Stonehenge; as a teenager I went to Stonehenge; as an adult I went to Stonehenge; and as an old man I go to Stonehenge. It tells me about my scale and the relative values of my experience. That side of sculpture is about the place outside of human time that somehow calls on us to register. I think this is a really powerful part of its “function”.

Antony Gormley. Horizon Field Hamburg. 2012. 206 x 2490 x 4890 cm. 67,000 kg. Deichtorhallen Hamburg, Germany. Photo: Henning Rogge. © Antony Gormley

At the same time, I love everything that has happened to sculpture in the expanded field. There are no material, constructional or conceptual limits to the potential of sculpture’s ability to demand our attention. I would like to feel that Blind Light wasn’t the end of my exploration of dealing with a direct first-hand experience outside of objects. Horizon Field Hamburg (2012) is also dealing with something similar – the big unstable form where collective life itself becomes a self-experiencing field. I think that also was pretty radical, and it changed the function of the museum which transformed from a treasure house of already known objects to become a vantage point from which we look out from the windows to the real world as a representation of our condition.

I will go on doing this kind of things. I still am searching for ways in which space itself works, like using acoustics or qualities of light as a material substance. I have this long-standing dream of making an underground work. It would be like a vast body, but you would not see that because its outside would be buried. But you could enter it. These volumes could be an expansion of your own body consciousness and work in a kind of acoustic and light way. So there still are things that I am evolving to do with an objectless proposition as in Blind Light, although there it was achieved with a highly technological process. But simply making void spaces underground allows the experiences and perception of the viewer to become the subject of the artwork. Can we still call it a sculpture? Maybe it does not matter, but it has to be a cataylst for a subjective narrative of self-awareness.

I am very drawn to caves and mines. I love all underground voids. I have just been to the Krakow salt mines – impressive, have you been?

No, I feel quite claustrophobic in underground caves…

I was very claustrophobic as a child! (Laughs) But I realised that in my fear lies also a great power and a potential of liberation. Anyway, these salt mines in Krakow were so inspiring. So I am hoping that one day in my very own Cappadocia I will be able to make a work that acts very purely on the body… There is something so wonderful about bunkers – the sense of silence and darkness that you get in any of the great underground cave systems like in Dordogne, France – Les Eyzies, Rouffignac, Pech Merle and others. I think you connect with some really fundamental relations between imagination and materiality.

Antony Gormley and the journalist Anna Iltnere in Stockholm

Bunkers are also a shelter from war.

Well, bunkers are really just humanly made caves, yes, they have this military connotation. I spent a bit of time on the coast of Jutland in Denmark, where all the Nazi bunkers have been washed out from the sand. And they are amazing places to go and see, these human-made structures with three-metre thick walls. And you listen to the wind and to the sound of the waves through these walls. It’s like you have got a new skull, and you are inside this kind of big head. You have a different relation to the elemental world, which is more purified and detached. This is a strange anomaly : an unearthed cave or an unearthed void. There are shades of bunkers in the expansion works here, these absolute forms. The Matrimandir in Auroville outside Pondicherry which replicates the great Boullee cenotaph for Isaac Newton are spaces that are designed like planetariums, but without any didactic nature and are made to give the body a new zone of space/time experience.

The last question is a greeting from my father, also an artist, whom you visited during your stay in Riga in the 90s. He asks if you still have holes in your socks.

(Laughs) Yes, I do! Right now I have holes in my right sock. Do you want to see it to make sure?