The Messenger of Fluxus For the 21st Century

An interview with Artūras Zuokas, the mayor of Vilnius

23/11/2014

“Fluxus” – from the Latin fluxus, meaning “to flow” – was used by the Lithuanian-born artist and visionary George Maciunas in the title of his 1961 electronic music anthology. Maciunas also used the word in the label that he invented with which to denote one of the 20th century's most notable avant-garde art campaigns, the Fluxus Movement. Along with Maciunas, some of the more high-profile participants in the movement were Nam June Paik, Joseph Beuys, Jonas Mekas, Yoko Ono, John Lennon and Andy Warhol among others. The anti-art format of Fluxus captured moments from daily life through the aid of humor, satire, musical actions, happenings, film and photography. The movement's active period lasted up until Maciunas' death in 1978.

New York's SoHo neighborhood, which had recently been saved from being razed down, was seen as the center of Fluxus back then. Today, 30 years later, a sort of Fluxus renaissance (in the shape of a neo-Fluxus initiative) is taking place in Vilnius, the capital city of Lithuania. Sights have been set in the direction of Fluxus by another Lithuanian endowed with a level of ambition not unlike that of Maciunas – Artūras Zuokas (1968), the mayor of Vilnius. Zuokas' objective is to further the legacy of George Maciunas, the “father of Fluxus”, by making Vilnius the capital of Fluxus in the 21st century.

Zuokas began his working life as a war-time correspondent covering Iraq, Chechnya, Georgia and Azerbaijan for Lithuanian and British media. Around the turn of the millennium, he entered the political arena and became the youngest-ever mayor of a capital city in Europe. Having served two consecutive terms, he took a small break before returning for a third term in 2011. Interestingly enough, the British actor Jeremy Irons took an interest in local Lithuanian politics by endorsing Zuokas. Artūras Zuokas has received several international honors, and has twice been elected Vice President of the Organization of World Heritage Cities.

While mayor, Zuokas encouraged several world-class architects to participate in reshaping the urban landscape of Vilnius – after the announcement that the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas was to be closed, it was soon after declared that Zaha Hadid had won an international architectural competition to develop a design for a proposed new Hermitage Guggenheim museum in Vilnius; Daniel Libeskind and Massimiliano Fuksas had also submitted entries. Zuokas also initiated the creation of an artists' quarter in the Užupis neighborhood of Vilnius, a/k/a the “Montmartre of Vilnius”.

International recognition came to Zuokas by way of his Fluxus-inspired stunt for a Public Service Announcement. He drove an armored personnel-carrier over a luxury Mercedes parked in the bike lane of a Vilnius street, thereby emphasizing the universally pesky issue of illegal parking. Zuokas received the Ig Nobel Peace Prize for this exploit, an award given for something that “at first makes people laugh, but then makes them think”. It was presented to him at Harvard University by Peter Diamond – that year’s winner of the actual Nobel prize for economics.

How did your interest and enthusiasm about Fluxus first come about?

In large part, of course, because of the fact that the movement's founder was George Maciunas, a Lithuanian. I was interested in the Fluxus phenomenon – this was one of the most important movements of the last century, and it influenced a great number of well-known artists such as Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, Andy Warhol, even John Lennon...

I was simply infected by the ideas of Fluxus! It's wonderful – this ability to look at daily life creatively. That's why I liked their motto, “Anyone can be an artist, but only the artist knows that he is an artist”.

The ideas of Fluxus seemed relevant to me, and I began to increasingly interest myself in them, and thanks to my good friend, Jonas Mekas, I also had the opportunity to personally meet members of the Fluxus Movement. Then it became much more personal because it's one thing to read about something, but altogether different to actually meet them and see their work in person.

So, you 'brought' Fluxus to Vilnius...

The City of Vilnius acquired the Fluxus collection, and now it owns one of the greatest collections of the Fluxus legacy in the world – it's the third largest after the ones held by New York's MoMA and at the State Gallery of Stuttgart. [The Fluxus collection in Vilnius was acquired from the movement's representative, the Lithuanian-American avant garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas who was also a close personal friend of George Maciunas. It contains about 2600 items, including works by George Maciunas, George Brecht, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, and the film and video archives of Jonas Mekas himself – A.Č.].

We've also opened the Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center in Vilnius that features works by the Fluxus Movement, Jonas Mekas and George Maciunas. This center has been operational since 2008. Since then, we've been thinking about how to keep the idea of Fluxus alive and how, perhaps, we could start a new wave of the movement. In the previous century, the capital of Fluxus was New York – why couldn't it be Vilnius in this century?

Jonas Mekas

What sort of activities are currently being undertaken to bring this plan about?

Numerous initiatives have been started. Besides the already-mentioned Jonas Mekas Visual Center and the acquisition of the collection, various exhibitions and festivals are being organized, to which we have invited artists such as Shigeko Kubota, Ben Vautier, and others. We have begun organizing exhibitions outside of Vilnius – in New York, Kiev, Tbilisi, Brussels. A very successful exhibition was last year's Fluxus: Russian Atlases, at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. In two months' time, 20,000 people visited it. It was the first exhibition of its kind at the Hermitage because, as everyone knows, it is an altogether conservative institution.

But returning to Vilnius... Various Fluxus ideas are used when organizing the city's events. . For instance, in the place where Lenin’s statue used to be, a sand sculpture of John Lennon was erected. [In 2012, with The Beatles' song Imagine playing as a soundtrack, a 100-ton sand sculpture of John Lennon was erected on the spot where the Lenin monument used to stand. The Lennon sculpture stood there for several weeks – A.Č.]. That's was a true Fluxus performance! I received a letter from Yoko Ono at the time – she was happy about the message that it sent, that the ideas postulated by Lenin were being replaced by John Lennon's ideas of humanism and peace.

The well-known incident with the tank and the Mercedes on Gediminas Avenue also fits in with this sort of performance.

That's one of the ways that I, as mayor, work for the good of the city. Through encouraging creativity.

Of course, the new wave of Fluxus is different and necessitates an altered approach. We're thinking about what Fluxus means today. But Fluxus is creative freedom. Anybody can be creative – it doesn't require any noticeable investment – you just have to start thinking a bit more creatively than usual.

Ministry of Fluxus in Vilnius. Photo: Augusto Didžgalvio

Could you tell me about the idea behind the Ministry of Fluxus project?

When the country was experiencing the economic crisis, which was especially felt in the real estate market, many buildings were left empty and untended. For a year and a half [April 2010 to November 2011], the owners of the building [which used to house the Ministry of Health] at 27 Gediminas Avenue rented out the building to us at a charitable rate. There we opened up the so-called Ministry of Fluxus, a place where artists could live for free, set up their studios, and work. At the same time, the building served as a place where people could organize exhibitions, performances, concerts, theatrical plays and film viewings.

In 2012, the Ministry of Fluxus moved from Vilnius to Kaunas, and into a former factory [which used to make Lituanica-brand shoes] in the center of the city.

These projects were short term because one of the main tenets of this initiative is impermanence – otherwise, sooner or later it will become a more bureaucratic institution than it should be.

A number of artists (including those from Latvia, Estonia, the Netherlands and Poland) joined the project and volunteered to exhibit. Many have said that it was a productive time for them because the places were really inspiring for their work. In addition, the 18-month time limit served as supplementary motivation for bringing their work to completion.

Interestingly enough, the ministry has greater meaning and fame now than when it was open. When established artists – who back then held their first shows at the ministry – present themselves now, they always mention that their creative careers got their start there. What's more... Once the project's term had come to an end, we gave the buildings back to their owners – but with an added value. Now the buildings have a history. For instance, the wonderful building on Gediminas Avenue will now be a hotel, and it will, in fact, advertise itself as the former home of the Ministry of Fluxus.

The building on Wooster Street. Photo: Amy McNulty

In realizing such projects, one often runs into a lot of bureaucratic red tape...

Of course, the problems were various and many, but if we look from the perspective of Fluxus – there are no problems. If we were to look at all of the possible limitations from the very start, then the idea would die before it even got up on its feet. We were... I don't want to use the word “illegal”, but in a sense, that's what we were. In our own kind of way. But this overstepping of norms relates to the Fluxus period in SoHo, when all of the artists' studios were actually there unlawfully . I like what Jonas Mekas said, “If a person is alive, he cannot be illegal.”

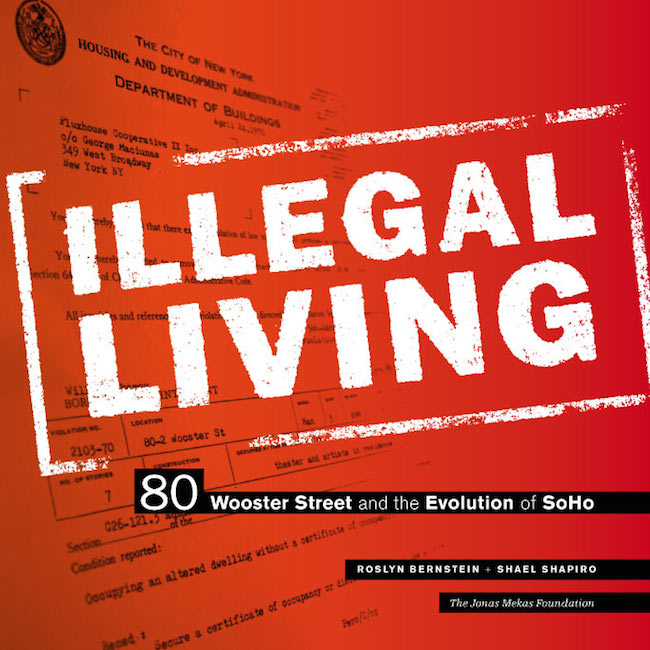

In 2010, we published Illegal Living : 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo, which takes a historical look back at the SoHo neighborhood in New York and the first so-called artist cooperatives established by George Maciunas. The book was written by a journalist and an architect from New York [Roslyn Bernstein and Shael Shapiro, whom Zuokas met in New York while preparing for the “George Maciunas: Father of SoHo” exhibit that took place in Vilnius – A.Č.], and it was funded with support from the Jonas Mekas Foundation.

The cover of Illegal Living : 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo, printed in Vilnius

Could you tell me some more about this book?

“Illegal living” – that's the label that the New York City Council used to designated spaces that were being unlawfully inhabited. The police could use force to evict anyone living in such places. But the artists who had moved into the abandoned buildings in SoHo rose up and eventually managed to legalize their habitats. And that was the birth of SoHo, which had previously been slated for demolition. If it hadn't been for these two Lithuanians – Jonas Mekas and George Maciunas – things could have turned out very differently. Now, SoHo is a site of cultural heritage on a global scale.

The book had a wonderful launch at the actual 80 Wooster Street in New York that was the site where Maciunas established the first artists' cooperative [In 1967, George Maciunas bought the brick building from Miller Cardboard Company for 105,000 US dollars. It is where he created the first artists' cooperative, Fluxhouse Cooperative II. This event is now widely accepted as the moment when SoHo was reborn, and as the beginning of the movement in which industrial spaces throughout the world are repurposed as residential areas – A.Č.]. Both Maciunas and Mekas themselves lived in this building. The book contains pictures of the bohemian way of life back then, and of the icons of the art world who resided there.

Now the building houses a shop. I arranged with the owners to borrow the premises for the one day of the presentation.

The book was sold in the world's best bookstores, and we're planning on putting out a Lithuanian edition.

Illegal Living : 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo presentation, New York

What is that building in the center of Vilnius which is currently being repainted black and white? It was a hot topic on Facebook yesterday (September 9).

That's a former soviet workers' union building. We'd like to buy it back from its current owners, knock it down, and build a concert hall with seating for 1500 in its place. We've announced a state-wide open call for architectural design proposals, but currently it serves as a great platform for street art and graffiti. I’d like to mention that we held a large-scale Vilnius street-art festival this year. The Ministry of Fluxus in both Vilnius and Kaunas were also used as platforms for large scale art projects. A catalog of Ministry of Fluxus street art was also published.

You have been awarded the title of “Friend of Architects” in Lithuania. Could you explain how that came about?

I am fascinated by this profession. I know many architects personally – not just from Lithuania, but on an international level. People like Daniel Libeskind, Massimiliano Fuksas, Frank Gehry , Zaha Hadid... I've also invited them to create projects in Vilnius. In 2008, I organized an international competition for design proposals for the Vilnius Hermitage GuggenheimMuseum project. Zaha Hadid won.

But now a Guggenheim museum is slated to be built in Helsinki. What happened back then?

As frequently tends to happen, one meets with opposition from the side of uncreative politicians. And from the side of jealous politicians. They did everything they could to stop the new museum from happening in Vilnius. But since I am again in the office of Mayor, the idea is being taken up again. It's not that simple – it's not going to happen tomorrow, nor the day after tomorrow, but we're on the right track.

Of course, the Guggenheim Museum is no longer our partner; it has moved on to Helsinki. But we have signed a contract with The Hermitage, and the idea is to open up a space here for the -Hermitage 20/21- program.

What is your opinion on what is going on in Helsinki?

We're following the events going on there. It looks like it's slowly moving forward for them, and I'm very happy about that. It will increase Helsinki's popularity as a destination for seeing quality art and architecture. I believe that the people who have supported, and who are supporting this idea – are thinking about the city's future. Of course, it is good if there is opposition and discussion that make one reevaluate ideas – I do value criticism – but only when it aids in raising a project's quality, not killing it. In this case, the story is similar to what had previously taken place in Vilnius.

What, in your opinion, would be the ideal liveable city?

Vilnius! It's an ideal place to live in, to work in, and in which to raise your children. And in which to feel as part of the global community. I tend to joke around, but every joke contains some truth – we are the Baltics' southern-most state, and in a certain sense, we have a southern mentality. I truly like the way Italy's small and medium-sized cities have been planned out. It's important for a city to have a living creative and cultural life. It must also be multicultural. And a city must also tell a story – not just its history. And the people that live there must be part of that story.

Apropos multiculturalism – does Vilnius seem interesting enough to foreign artists to come here to work and live?

Yes. The artists that have been here readily come back again and again; some choose to stay indefinitely. That's a good sign.

How are home-grown artists doing in the world art market?

The only problem is that in the context of the global art market, we're a small country and a small city, and that's why we don't have enough resources with which to stimulate our own artists' participation in global processes. That's why it's important to be part of an international movement and that's why Fluxus is a singular opportunity.

This has always been a dream of mine, which has yet to come true, but maybe someday – I wish the city could obtain some of the best real estate on the main streets of Paris, New York and London, and open up galleries for our artists there. That would be the best marketing ever for the city, and the best way to present the accomplishments of our artists in the world's art megalopolises.

Every year in Lithuania, three times as many students graduate with art degrees than in, for instance, Norway. We have to find a way to support them because it is obvious that the local market is too small. That's also why we organize the art fair ArtVilnius every summer. We support artists as much as we can within our limits, and we support the participation of our galleries in various large art expos.

What is the situation in terms of support for the arts coming from the private sector?

It's growing. Interest in contemporary art is especially growing. They are mostly business people – they invest in art, and promote collections on not only a local level, but on an international level as well. And that's a way to raise the value of art.

Like with a jigsaw puzzle – by putting together everything that I've told you today, there will soon be a whole picture to see!