What You Hear

An interview with the Estonian artist Raul Keller

Sergej Timofejev

02/12/2014

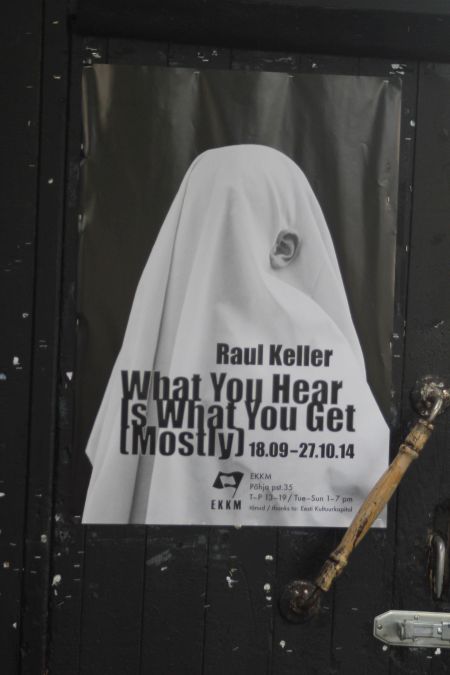

Raul Keller arrived for his interview on a motorbike. Tall, dressed in a black leather jacket, black hoody and black trousers, with a blue pirate’s kerchief around his neck – an amiable, calm and unhurried fortyish man who loves to connect space and sound, bringing the two together and observing their relationship. A graduate from the Tallinn Academy of Art, he is a lecturer himself now, as well as the Chair of the Department of Interactive Multi-Media. Keller frequently shows in Estonia and abroad; the latest of the three solo exhibitions held in 2014, ‘What You Hear Is What You Get (Mostly)’ ran at the Estonian Museum of Contemporary Art (EKKM) through most of October. The ‘mostly’ refers to a collection of various half-mysterious objects that were placed by the artist in the galleries of EKKM alongside the sound. They included half-dissected barrels, suspended in the air and looking like giant accumulators for God knows what devices; a curtain that opened in a completely dark room, reacting to movement, and invited you inside the circle it formed under a rectangular red-light lamp hanging from the ceiling; emerald-tinted smoke that quietly flew from itself into itself. And yet the main dramatis personae here was sound: booming, monotonous, sucking you in, emitting energy, changing its pitch and intensity from object to object. On the whole, you felt as if you had found yourself inside a spaceship of an antediluvian civilisation. The spaceship flies; the machinery works just fine, and yet you cannot for the life of you neither make out the principles of its work nor guess the appearance of the living beings populating the ship. And all of that is housed on the premises of a long-since defunct thermal power station that is home to EKKM.

We met outside the museum; the weather was perfect and there were some thirty or so high-school kids at the entrance. The director of the museum Anders Härm was explaining to them in Estonian the basic principles of sound art and taking them on a tour of the three stories of the exhibition. We retreated to a nearby cafe and settled down by one of the street-side tables. Alongside Raul Keller’s voice, my dictaphone also picked up the sounds of the occasional passing car, fragments from our neighbours’ conversation, all sorts of screeching and beeping noises.

While preparing for the interview, I searched the internet for your works that could be viewed online. I must say that I found next to nothing...

That’s true; I haven’t put that much of my stuff online. And I don’t do recording very often. The actual creating of the objects demands too much energy. And even when I do record my own works, as often as not the video stays in my archive. Because I don’t really believe in that sort of self-promotion. It may seem that it’s very easy to form an opinion about an artist or an exhibition judging from a single video. But it is very likely to be a simplification of sorts.

I know that we are getting used to being able to access loads of information online. It’s just that I’m not sure if I want to encourage that and cater to the customs of the media age. Yes, you can find information about me but, for the most part, it is what others have written about me. And even these critiques feature at least some factual errors. In any case, they don’t reveal the gist of the story.

I figured that this might also be due to the fact that sound art-related works hinge on air and its physical laws. And you cannot record air on video.

It is also true. Recording things of this kind is very difficult. For instance, the set-up of this exhibition is based on the principle that, as you change your position in space, you also change your perspective of sound. It is, of course, possible to walk everywhere with a switched-on camera or record the sound separately... But in any case, it is not going to be quite the same. And it is very tricky to shoot anything in the dark (and some of the works are shown in darkened rooms).

I think that spending some time in the dark is always a powerful mediator. You lose some of your senses while others sharpen. Particularly your hearing.

Some artists deliberately try to eliminate any visual information at their concerts. And when I hear something complicated that demands special attention, I tend to close my eyes. That’s all understandable. But I do not make installations in complete darkness. That would be quite a challenge for the viewers; people just don’t feel comfortable. Even at this show, some of them feel quite awkward because of the partial darkness. Many people perceive darkness as something gloomy. I personally don’t see any connection between the real darkness and the symbolic one – you know, powers of darkness, that sort of thing. To me, it is rather an opportunity to focus. And that’s why I find it quite strange when someone finds something scary in my work. It’s something I haven’t even suspected of being there.

I don’t think at all that an artist must scare or shock the viewer in any way. I have absolutely no ambition to do anything of the sort. I try to communicate with the viewer. I simply offer him a different experience – to immerse himself in sound, immerse himself in this particular space. The phenomenological aspect of things. And sometimes it is dark in there – or rather, somewhat darkish.

How do you select the sounds for your work?

I try to stick to a minimalist approach. Most of the sounds are simple sound oscillations or some sort of sound waves. When I ‘tune’ my objects, I choose the main resonance and then tune the frequencies depending on the sound of the actual space in which the object is shown – depending on how I hear it. It is quite an intuitive experience. And when I find something that allows the space to open up, to stop being closed – I think I find an extra level of openness. Sometimes it takes me longer; sometimes it happens very naturally. For me, it is this stage that gives me the most pleasure: when everything has been set up and switched on, and you can sit down and tune the whole thing together – tune the aggregate sound. And I always wish I had more time left for this part – just to calm down, sit down and feel the space through the sound. Sadly, the set-up process often takes much longer than planned, which always leaves me wishing I could spend a bit more time dong this last bit – so I could do it with pleasure.

Does it happen a lot to you that you are, let’s say, travelling, and suddenly there is this exciting sound...

(Right at this very moment, we hear a very unusual sound coming from the direction of the port. Raul Keller makes a resigned gesture, as if saying – See?)

Of course. When I travel, I always take some sort of sound-recording device with me. I don’t use these recordings for my installations, though. I am more likely to use them in some sort of compositions for audio CDs. I mean, something also for home listening, that sort of thing. Sometimes I record different musical instruments – just for the sound of the instrument, not for the melodies. I don’t use sounds like a logical language; the sounds do not carry a specific meaning.

Which means that you lose interest if a sound is too concrete?

I am not referring to a conceptual ‘interestingness’. I am interested in a particular sound, a particular sonic character that I can achieve using ordinary tools, ordinary sound oscillations. If I happen to hear anything like that in real life, as often as not it’s something like a chopper flying overhead and creating these sound waves. If I used sounds that I had recorded somewhere, it would be a completely different approach. It would add a certain narrative to the whole thing. And I don’t work with narratives. I work with objects and structures. A narrative is created out of the very process of creation. I do not attempt to illustrate anything. First I think of the sound I would like to achieve; then – of the approach; then – of the process of realisation. And then the actual process of realisation starts to influence the end result. Sometimes I suddenly see that a work is completed, although I had initially planned to add something more.

Do you recall the first work of sound art that you saw and heard? Did it influence you and your approach?

That is a good question... (Thinks.) I don’t think I was influenced by a single individual piece of sound art. I actually have quite a serious rock background. Gradually I started to pay more attention to details in the music. I had no musical training. And yet I started to wonder how sounds are actually born and why it is that I find some of them more interesting than others. And that is how I started to progress along this road – feeling my way, simply listening and focusing on my reactions to different nuances of each sound. And then I discovered for myself the minimalist composers, including Steve Reich. And I rediscovered for myself the sound of percussion instruments which actually not only make the rhythm but can also act as melodic instruments. And eventually I started to realise that there was a specific type of repeating sound that somehow reacts, interacts with me.

For instance, I had an electric guitar. But I never learnt how to ‘play’ on it. I simply liked some special sounds that I somehow managed to draw out of it... Basically, I cannot claim that it was a conscious choice on my part; it’s just that sound started to interest me more and more.

At the same time, you are a professionally trained artist?

Yes, I have worked a lot in video and in performance. And I discovered for myself that all time-based media have a lot in common. An audio-visual work cannot be split into individual elements. When I worked in video, I did, of course, notice that you can use the technique of scratching with a video recording in the same way you would with a vinyl record, and the result is a very interesting sound. I am still interested in moving images. Speaking of drawing, I started to do that some twenty years ago, and I still do some sketching. I just don’t show my works. And as for painting – I still don’t get it: why should I make a single painting? What is the point of a single painting? I do work in photography, though, and I love the process of analogue photography. And sometimes the meaning of a photograph emerges from the process of its creation. I believe that the most important thing is to lose yourself in the process of creation, and then the piece will find its own meaning.

But why can’t it happen with drawing?

Of course it can. But it’s still a more narrative process, an illustrative process. Although it can also be abstract, of course. But the next step in an abstract approach is the material itself. And this is where I would probably become interested in the quality of the paper and the ink, for instance, and the way ink dries on the surface of the paper. I love textures and tactile qualities, I love them very much. It is almost as if they were inviting me to play with them. I walk into a shop and see a wonderful paper for drawing. Immediately I start to think of the best way of using it. Which would be the best colour for it? I try to find something commensurate with the actual idea of this paper.

But it is, I suppose, one of art’s missions – to give voice to these things, to let their inner essence reveal itself.

Definitely. On the other hand, it is also an industrial artefact – this paper. It is a thing that certain people have produced as a result of a certain process. And to a certain extent you as an artist are programmed to like it. You walk into this shop and it’s like you’re a child in a toy store all over again. And the same thing can happen in a music store: so many instruments, each with a sound of its own and a perfect texture. And to an extent, the industry manipulates you: you are transformed into a consumer. And I am always afraid of that.

A funny thing: when I get some money for an art project, I usually reinvest it into the industry that produces all these things, be it fabrics or special steel constructions. So basically all these talks about artists being parasites who only know how to spend public money – they are very far from the truth.

When I was at your show, I had this association with science fiction, circa 1960s--1970s. And then this story started to emerge, something to do with an abandoned spaceship on which you somehow find yourself... All these weird instruments working and making all sorts of sounds... What are your own feelings regarding the exhibition?

They are completely different, of course. To me, it is first of all a process, and a very physical process at that. Having visited this place and later imagining it, I tried to transform this space and our perception of it into something different. The result is an open system. If you say that it is reminiscent of something out of science fiction – why not. I am always very interested in feedback – in the fact that a certain narrative crystallises in the imagination of the viewers. I personally tend to associate it rather with some sorts of boxes with sounds inside them, which people can move around and change the sound. Something along these lines.

On the third floor, where there is the room with smoke coloured by the spotlights, a young girl walked in ahead of me. She jumped over the barrier and sat down right on the border of the smoke – presumably to examine it better. When you set up your installations, do you imagine/plan how people are going to move around there – how they are going to behave? Because there is also this space that you can see but cannot reach. You can see that it is there but you cannot enter it.

Yes, you can walk up the staircase behind which a room with an amplifier is visible, but you cannot enter it. And that is exactly one of the cases when a space starts to offer its own versions during the realisation of the idea. The initial idea was quite different – simply to block the room with an amplifier that is more powerful than the rest of the objects. You can walk up and stand on the ceiling of the room and sort of hear that there is something there. And the top of the room is also scattered with pieces of soundproof material, so that the sound is even more ‘washed-out’. But when we started to put all the stuff in the right places, it turned out that we didn’t even need to screen off the room. It works the way it is: you see the room, you hear the room and yet you cannot enter the room.

Of course, I have my own idea of how people should be moving around the exhibition space. But people will be people. Perhaps climbing over the barrier was not a very wise thing to do because there is practically no oxygen at the spot where the smoke is the thickest, it’s almost pure CO2. By the way, there is a video camera and a girl who is an attendant is watching everything to avoid accidents.

I was here on Tuesday, trying to record something after all. At the time, five kids around 15 or 16 were visiting, and I saw them enter the room with the curtain and the red light. And they started imitating animals and roaring. You just cannot predict things like that. Someone tries to catch every nuance of the sound, layer after layer. And someone simply senses the energy that emanates from the piece.

And sound is the quintessence of energy.

Yes, it is naturally very powerful. And it carries lots of information. We hear so much more than we ever see. We try to focus on sight because it is the main one among our senses. But audio information reaches us much faster. And it heads directly to our brain whereas eyes have to reformat light into a signal for our nervous system. Also, the spectrum of the visible light is much smaller than the range of sound. It may be connected with our evolution as a species because there was a time when we simply had to hear the slightest rustle. It is enough for a small branch to snap under someone’s feet in the forest, and our body reacts immediately. But if you want to see something, you sort of scan it and then you start to distinguish the lines, the silhouette. Whereas, if you hear something, you react at once.

You also work in the area of radio art. Could you tell me about the project?

It is called LokaalRaadio, and it’s closer to performance: it’s as if each concert becomes a radio concert. We use a radio transmitter and broadcast to a selected small area – a very small one. Hence the title – ‘local radio’; it is indeed very local. We improvise and also use pre-recorded things. The ultimate lo-fi.

In 2011, we held a radio art festival entitle Radiator. Right here, at EKKM. It was a programme of concerts and talks, and everything was broadcast in a 3-kilometre radius. And we also broadcast it online. So that some people came to the event, some listened in on the radio and some watched it online.

Things are quite simple and minimalistic at our gigs. It is very different from the recently very popular community radios that try to emulate the existing formats of radio broadcasting: first someone is performing at the studio, a sort of live event, then there is a sort of conversation followed by a bit of music, then – local news, etc. We have something completely different going on on-air: noise and hiss.

The age of mass communication, the age of television has brought imaginary collective experiences into our life. The same goes for the radio. There is a great difference if you are listening to a song from a CD at home or if you hear it on-air. It means that someone else is listening to the same thing simultaneously, and you get this sense of community. And all this hissing between the stations, also a certain electromagnetic matter – I find it interesting as a medium.

When I was a child, we also had a radio set at home. Father listened to the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe. What I liked was slowly, slowly turn the tuner knob, moving from station to station, from language to language: here are the Chinese; here are the Vietnamese; here are the Hungarians.

A chance to capture the whole world at once in your radio set.

Yes, it is not such a bad idea of travelling.

Is there a specific project, an idea that you haven’t realised yet but would love to?

As a child, I had this idea that it would be great to control sound in the whole city. (Laughs) That’s a crazy idea – that you could become the composer of a soundtrack to the whole city. That’s a joke, of course. I suppose the idea was born from the time when we used to have all these May Day demonstrations and parades. They had these loudspeakers, sirens, music in the streets, speeches... Like one huge soundtrack. And so, as I was walking home from school, it occurred to me that it would be great if I could write this whole soundtrack on my own.

Generally speaking – I am open to challenges. A new challenge means the beginning of a new stage. If the challenge is too big for me, I fail. If not – everything sort of comes together in the end. And I don’t know what the next great challenge will be in my life. Maybe it’s already all happening right now, as we speak.