Combined Forces of Art: Gilbert & George

An interview with British artists Gilbert & George in London

Agnese Čivle

22/04/2015

Two people, one artist. Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, Peter Fischli & David Weiss, Elmgreen & Dragset, Jake and Dinos Chapman (Chapman Brothers).... The British artists Gilbert & George also definitely fit in this list of combined forces of contemporary art, although they began in 1968, much earlier than any above artists.

Gilbert (1943) and George (1942) made their début in museums and galleries more than 40 years ago with THE SINGING SCULPTURE. Dressed in their trade mark conventional suits that have by now become their uniforms, their faces covered in multi-colour metalic powder, they played the music-hall classic Underneath the Arches on a ordinary cassette player, climbed up onto a table and sang along and moved for hours, all the while executing a robotic dance routine. Back then, when they were still young and naive, all they wanted was to announce themselves to the world. Even though they still didn't know it, they had found the ideal format – people stood and stared at the LIVING and SINGING Sculpture as if hypnotised. Reminiscing on this legend a couple of decades later, the museum souvenir manufacturer Kit Grover even came out with a clever toy called The Singing Sculpture.

THE SINGING SCULPTURE, 1970. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Already from the very beginning, Gilbert & George placed themselves at the centre of their art in order to follow the “live sculpture” setup, at once becoming the object and subject of their artwork and melding their art and daily life into a single whole. Gilbert & George were not alone in wishing to become the artist, for in later 1975, Gilbert & George commisioned the German artist Gerhard Richter for his series of portraits of creative individuals. Some of these paintings can now be seen in the National Gallery of Australia.

Interestingly, the romanticised myth about the artist as lone wolf applies in part even in situations where the artist is not one nor alone. In avoiding any kind of quantitative communication – whether it be the growing gigabytes of email, other artists' exhibition openings or discussions with curators – Gilbert & George have always tried to maintain a certain feeling of isolation around themselves. In a way, the two artists are like a lonely planet circling around the orbit of society, watching it from a distance.

They observe what happens around themselves – the evolution of London's East End and the street life on Brick Lane. You see, they've been living in this part of the city for almost fifty years, this area that was formerly located outside the city walls and was home to a string of noisy and smelly industries, from textiles to brick works to dye works. From the very beginning, this part of London has been inhabited by immigrants – Huguenots fleeing from France in the 18th century, Jews in the 19th and 20th centuries, and now Bangladeshi immigrants. As the cocktail of nationalities becomes ever richer, Gilbert & George are convinced that the East End is like a miniature model of global society. And that's enough to not have to go anywhere else for inspiration. Their art grows out of this reality, out of Brick Lane and adjoining Fournier Street with its 34 houses sheltering people from countless ethnic groups – rich and poor, Protestants and Islamic fundamentalists, atheists, artists, bookmakers, silk weavers, taxi drivers and film stars. This is also where they create their pictures, in a three-storey red brick row house built in the 18th century that has, in addition to living quarters, a perfectly organised studio.

CHRISTIAN ENGLAND (2008) from the series JACK FREAK PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

In their more than 40 years together Gilbert & George have created more than 2000 pictures. They are represented by two of the most prestigious art galleries in the world, Thaddaeus Ropac and White Cube. In addition to many private collections, their pictures can also be found in Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum, which hosted the first retrospective of the artists' art in 1980, as well as the Guggenheim Museum, which soon after organised their second retrospective in 1985. That was followed in 1997 by a retrospective at Paris' Musée d’Art Moderne. Only after 2005, when they represented Great Britain at the 51st Venice Biennale, were Gilbert & George honoured by their own native Tate Modern. There their exhibition, the first of British artist at Tate Modern, occupied a whole storey of the museum, a feat only the late Andy Warhol had pulled off before them.

In 2008, the artists sold their artwork TO HER MAJESTY (1973) for 3.7 million dollars, and it is still one of the most expensive photo based pictures ever sold, alongside Cindy Sherman's Untitled #153 (1985), Andreas Gursky's Los Angeles (1998) and 99 Cent II, Diptychon (2001) and the new record, Peter Lik's #1 Phantom, which was recently sold for 6.5 million dollars. Gilbert & George, however, never call their photomontages photographs; instead, they are pictures.

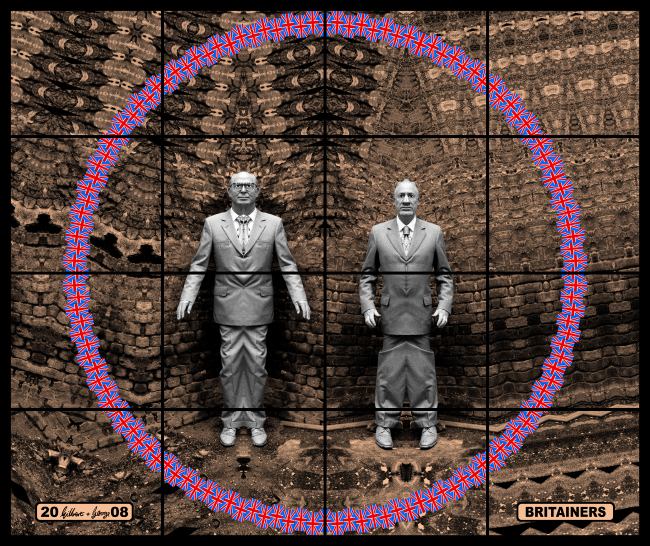

In their picture cycles, the two artists examine themes such as patriotism, immigration issues, tolerance and intolerance, as is the case in JACK FREAK PICTURES (2009), in which the dominating illustrative element is the Union Jack, Great Britain's internationally known, abstract, geometric trademark, a socially and politically charged symbol whose meaning covers a broad cultural spectrum from contemporary fashion to aggressive nationalistic pride. Gilbert & George are, of course, always the main actors in their works. They are thereby both the subject and object, the art and the artist. Their bodies sometimes seem whole, sometimes fractured; they fall from the sky and land in the middle of the street, other times their talking heads become bums.

KHILAFAH (2013) from the series SCAPEGOATING PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

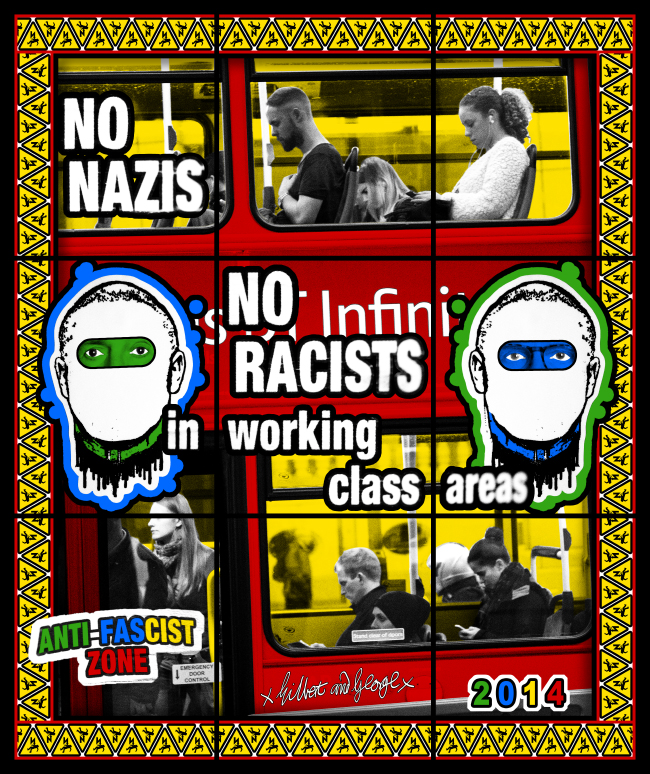

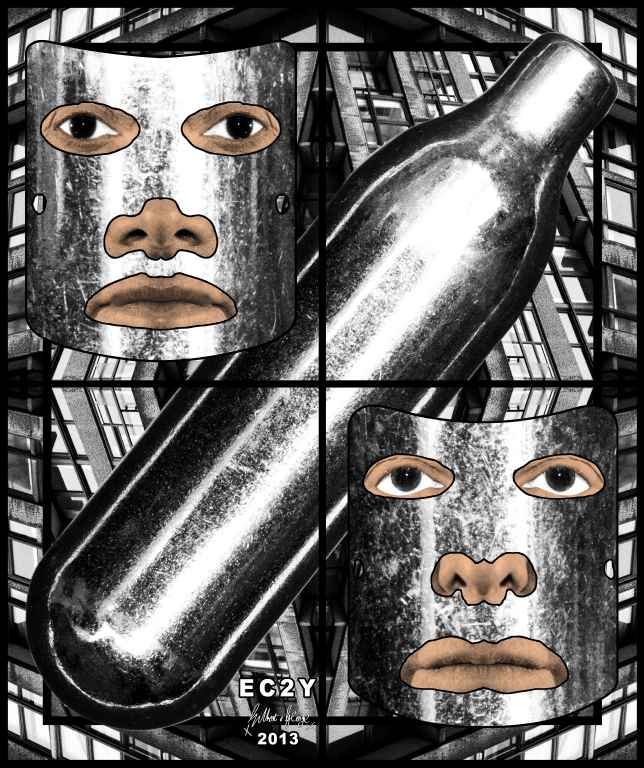

Gilbert & George's SCAPEGOATING PICTURES (2014) series, in which they portray Muslim drug addicts with balloons of laughing gas that look like grenades and women dressed in niqabs, they are clearly reflecting on their paranoia of an Islamic invasion, on the tension now palpable among the residents in many areas of London and elsewhere. Currently, Gilbert & George's first solo exhibition in Singapore is on display at Berlin’s ARNDT gallery affiliate until April 12. In it, 26 works from their newest group of pictures, UTOPIAN PICTURES, show the artists' utopian vision of our modern world. This vision has been presented in the form of warning signs and consists of authoritative instructions, laws, advertisements and infographics, dogmas and warnings, threats and unending proclamation.

When I arrive at Fournier Street, Gilbert and George are planning and measuring an exhibition that is intended for the possibly most distant art museum in the world, Tasmania's MONA. There, on the banks of the River Derwent in the Hobart suburb of Berriedale, stands the gigantic concrete and steel construction created by Australian mathematician and art collector (and professional gambler) David Walsh. Walsh has invested 75 million dollars in the museum project. Gilbert and George, for their part, have created an exact model of the museum space in their studio. They have placed matchbox-sized pictures in the miniature exhibition halls and reserved room on the walls for accompanying texts. The artists have even designed the benches for visitors to sit on.

Even though back in 1967, when they met at St. Martin's School of Art, George was the only person who could more or less understand Gilbert's poor English (Gilbert was born in Italy), today it is Gilbert who dominates the conversation. We talk for precisely one hour. Gilbert and George's lunchtime is at 11:00 AM, and together we head to Smiths by Old Spitalfields Market, where the staff already knows to turn down the music when the artists arrive. They don't like loud music while lunching.

ANTI-FASCIST ZONE (2014) from the series UTOPIAN PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

You recently returned from Singapore, from the opening of the exhibition of your newest pictures, UTOPIAN PICTURES. How did your artwork make it to Southeast Asia?

We have been represented by Berlin’s ARNDT gallery, and ARNDT has a gallery branch there. Its owner, Matthias Arndt, feels that Berlin is a bankrupt city – it is very difficult to sell art there. And he realised that the market in the Far East could be very important. Now he lives in Singapore, and he invited us to do show there – in a beautiful gallery district in the Gillman Barracks, a former colonial army base. It now houses the Centre for Contemporary Art as well as outposts of major galleries like ARNDT.

What did you think of Singapore and its art scene?

We loved the way in which the city is moving. And thriving. It's covered with flowers. When you arrive at the airport, there are orchids!

The city landscape is covered with skyscrapers, but beautiful ones. The most famous architects, like Libeskind and several Dutch architects, have worked there.… And then there is the Marina Bay Sands hotel – three towers and a boat. It's the second-most-expensive building in the world! There everybody has to be rich; if you're not, it’s not good.

They’re still thinking about art. They have the money there, the buildings there, but they still don’t know what art is. For them, art is a new idea!

At the same time, there was an enormous art fair there. It was more beautifully laid out than the one in Paris.

Actually, we don’t like the idea of art fairs….

What do you think of the huge current art fair phenomenon?

Normally we never go to art fairs, but we were in Paris by accident. They lower every single work down. Everything is the same. You don’t think, “Oh, my God, this is a fantastic artwork”; you just don’t feel that, because they're all the same. It’s because of quantity. Lousy artists come up a little bit – they are in a great place out of their dirty studios, they are framed and hanged, and boys and girls are selling them, but famous artists go down.

What was it like before, when art fairs had just begun?

It was different. In the 1970s we used to do one-man shows, like that one with the RED MORNING pictures at the Sperone Fischer Gallery booth at Art Basel in 1977. It’s interesting, but they didn’t sell even one work. It was the leading gallery at that time, and we did THE RED SCULPTURE every single day. Our stand was surrounded by four or five other leading galleries – all had exhibitions of artists. And they sold everything. It was strange.

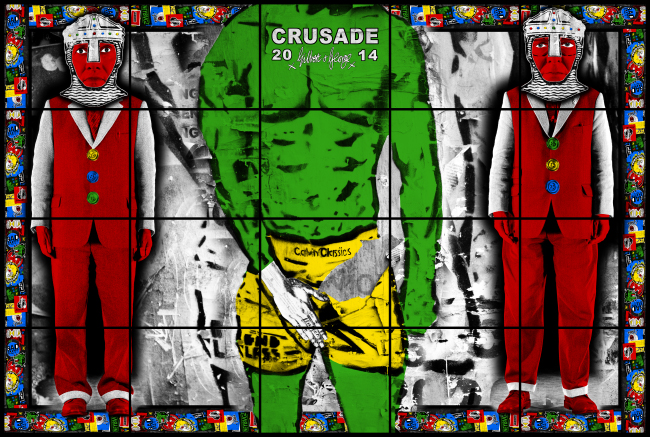

CRUSADE (2014) from the series UTOPIAN PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Returning to the Singapore exhibition.... How and how long did it take you to make the 26 artworks in the UTOPIAN PICTURES series?

Pictures always go back longer than they were created. The subject, the material, the thinking and feeling…. It took six years. During those six years we collected the material, researched the subject, and the physical creation of the artwork is the last thing. We took images of stickers you can find around this district, but we didn’t use them, because for a long time we didn’t know how to do it. It took five years to get to the point of yes, we will use them under the subject of “Utopia”.

For every new group of new pictures we take new images. In this case, we found the way to remove those stickers. We used a can of lighter fluid, squirted liquid on the sticker and very slowly removed it. And a can like that fits in the pocket perfectly! Other artists would say they don't go out without a sketchbook; we say we don’t go out without our lighter fluid.

What is your concept of utopia?

We were designing pictures for the show – one after another – and then we wanted to give them a title.... It's very strange – all sign systems tell us “don’t do this”, “don’t do that”, “stop this or that”.... But nobody really does it! But if you go to a nice town in the middle of England, where nobody vomits, nobody pisses, nobody breaks windows – there are no signs against those things. It’s very curious! Nobody needs to stop doing it. But when there are those prohibition signs, people go ahead and do it. Maybe the signs are giving them freedom?!

That is probably utopia. A total freedom in which you can roughly do whatever you want. But when you look it up in a dictionary, then you see we took it the wrong way, because the dictionary says that utopia is unattainable. We say no – it is attainable. It’s here! When you look around the streets of London, you see exactly what is going on in the world. We have always said that whatever happens on Brick Lane will happen in the rest of the world within two or three years. It's all growing here, it's the beginning of everything. The young artist, young filmmaker, young writer...they're all here. And they're not only English; they're from everywhere. And here is where the utopia appears – all those boys and girls, they sit on the edge of the pavement and eat and drink and do whatever they want…. They could never do that in their hometowns! People find the freedom here that they do not have in their own place. The same thing we did when we came to London.

BEHAVE (2014) from the series UTOPIAN PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

How has London changed since then? What's the smell of London today?

It’s not curry any more! That’s for sure. London's East End used to mean curry. That’s changed. Now it’s a more cosmopolitan smell. You can find any restaurant here – a Turkish one, a Finnish one, an Argentinian one, a French one, a Spanish one…. And those smells are totally different. You can even find Nordic sandwiches! Everything has changed. There's even one very posh Spanish restaurant in the most unlikely part of Brick Lane, where it's full of rubbish on the street. And there's a big sign outside that says in Spanish “street-friendly restaurant”. And they used to peel grapes for cake in that restaurant! Peel grapes!

Yes, everything has changed around here, because all young people want to succeed. Hippies are finished! They don’t think like hippies any more. They want to succeed and become something. They want to become filmmakers, designers, musicians, terrorists or whatever!

Do you think they will succeed?

We do! They will succeed more easily than before. They are so active! We were in Paris recently – the people are used to having coffees in their pavement cafés, but here in London they all have their coffees and are making deals! There's no time to just drink a coffee.

Is London still fertile soil for a new generation of artists?

Yes, it is! There are pop-up galleries here and there; every backstreet has a gallery. It’s funny – everybody you meet, they all say, “I’m an artist.” Everybody seems to be an artist today. Hundreds of thousands of artists! It didn’t used to be like this when we started. There were very few artists then, maybe forty or fifty people. We sit sometimes and watch the stream of young people, and mostly the girls are carrying canvases…. It's extraordinary! We don’t know where they will go, but it’s quite good because everybody has walls, there are many walls in the world. Twenty years ago people used to buy cheap prints, but now they can buy originals. And it’s good art – it's a kind of open democracy. Everybody is allowed to say what he or she wants to on their canvas. It's the free spirit. And we feel that democracy is the only way to run a country. Speaking, having a view and putting it on a wall – that is a part of that. Changing views, changing how we feel, how we should govern ourselves, how we should see the world of tomorrow, what we accept, what we don’t accept – it’s all part of an amazing movement of changes. Not like a religion that's standing still. Visual art, filmmaking, books – they are changing the world. Art and the artist are the least regulated. You can show whatever you want on canvas. It’s an extreme freedom to be an artist!

BRITAINERS (2008) from the series JACK FREAK PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Despite the fact that art has become a regular business, the playground of the rich?

Money laundering it is.

This auction art – what is this? What does it mean? But it's nothing new – it's always existed. For hundreds of years people collected the most expensive postage stamps, during the Renaissance artists painted for kings….

But for us it's very simple – the most important part of art is speaking, not making money. Having a vision, having an opinion, standing out.... Of course, we are happy if we can sell some. But what other artists want to do, that's up to them.

When we did THE NAKED SHIT PICTURES, we thought probably 90% of the world’s collectors would never touch it, so that’s it, but it's still freedom of speech. If every collector gave a chequebook to teenage children, then we could sell everything!

EC2Y (2013) from the series SCAPEGOATING PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Do you consider yourselves outsiders?

We have found a form, a new form for how to make art through the idea of the negative – to make an image out of the negative. Yes, we do feel like outsiders and we like it. We are totally free. We don’t go to openings because then we must be nice to artists and people, but we don’t want to. We're normal and weird at the same time. Normal weird.

Still, there's the simple fact that we are able to reach a very wide audience. We know it from the letters. And one of those enormous trucks delivering steel once stopped and this middle-aged skinhead shouted out the window, “Oy, my life is a fucking moment, but your art is an eternity.” It's very funny and very moving.

You could nearly say that no provincial English institution has hardly ever purchased us in fifty years. Hardly one museum!

They did exhibitions, though….

And every time we initiated a battle for it. They only showed our art because they were embarrassed to not do so.

And what about the retrospective at London's Tate Modern?

It’s very simple – we made them do it. We had to fight like dogs. And not only that they did not want to do it at Tate Modern; they offered us Tate Britain. We said no, we don’t want Tate Britain, because you have modern art in the world and then you have English modern art. We don’t believe in British modern art.

Why did you want it at Tate Modern?

We wanted to reach people! Everybody you stop on the street will say the same thing – what will be the next exhibition at Tate Modern? They think art should be like football – every week! That’s why every artist would like to have an exhibition at Tate Modern.

FIGHT NIGHT (2014) from the series UTOPIAN PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

After opening at Tate Modern, you had a party in a church….

Yes, here, at Christ Church in Spitalfields. They rent it out for parties. For years it was a dump for pigeons, then they restored it and it became an event centre, except on Sundays. We tried to find a space for 250 people. We had to pay 8000 pounds.

It was great to have a party in there, because one of the previous vicars of that church, a great friend of Mary Whitehouse, once appeared on television in a documentary and was very anti-us. He was also an activist of anti-gay campaigns. He was one that said we are sick, sad and serious. Are we? (Laughs.) And we are anti-religious. Ban religions and the whole world will become much better!

Do you believe in God?

We don’t believe in Jewish fairy stories! People invented God. Everything is invented by human beings. They say he's in the sky, but if you had space travel, you wouldn’t see anybody there.

Do you have your own rules?

We have. We are very disciplined. Everything is roughly in its right place.

In the film The Secret Files of Gilbert & George (2000) by Hans Ulrich Obrist you said that you must stay very organised to be creative and crazy. Is it still the same?

It is the only way we can just concentrate on our pictures.

We are free to do 26 UTOPIAN PICTURES and to get them out to thousands of people. And no one can stop us! We are privileged. We can create what we like and share what we like. It's total freedom.

ICH DIEN (2013) from the series SCAPEGOATING PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Do you answer emails and phone calls by yourselves?

No. But we did for a long time! We get exhausted. And now it’s much better, because we can decide everything later and we can stay concentrated. Not confused by other forces.

We actually don’t like emails. We are very anti-that. We arranged that our assistant opens emails just once a week, on Mondays.

People don’t buy envelopes and stamps any more; they email each other like idiots. It's a very destructive force, in some way. Everybody can write whatever they want and abuse it. But here is our latest letter written by hand.... Extraordinary, from last week!

Dear Gilbert and George,

I hope this letter finds you quite well. I write you to let you know something rather charming. My one-year-old son through the past two weeks is taking to saying goodnight to you both before his bedtime. We have a poster from your SONOFAGOD PICTURES exhibition. And each night he walks up to it and says goodnight to you both. I have to apologise to Gilbert because he says 'Jilbert' instead of Gilbert. I was moved to write because over the past few days he is taking to blowing kisses to you, too….

Sweet! And here is another one from a 13-year-old boy:

Dear Gilbert and George,

I don’t speak enough English, so I use Google Translation software to write in English. I find what you doing there four years ago, when I went with my parents on a trip to Brussels. I saw a show that I really liked. Photos, colours, poses…. I thought it was funny, and I often think if this not traumatised me a little. If I’m writing this, it’s because last summer I wondered if I’m not gay. I was always a little girl, especially since your show in Brussels, in fact. And my only friend in school also is a little girl and is rejected by others as well. This summer, while I was in the beach lying on my stomach I started to be bent when I saw guy undressed is going swimming. Since it frightens me, I ask myself question – am I gay? …. Thank you for your advice, because you are at least who could help. And happy St. Valentine’s Day!

These are confusing things that sometimes an artist has the ability to change and to affect.

Do you collect letters like these?

We have collected every letter. We keep every letter that is personal. It’s quite important to us.

You are quite passionate collectors, actually….

Very big collectors!

What does collecting mean to you?

Relaxation. Sometimes we have to relax, when we concentrate too much on art. To get away from it, to go back to zero, to wind up in a particular project and thought line.

We have thousands of books, furniture, vases, whatever you could think of….

It started like this – we restored our own house in 1973-1974, and we did it all by ourselves. After that we had all empty rooms and only two green chairs that belonged to a different period. Then we started to think about what could we have – because we cannot have empty rooms. So we became involved in 19th-century Victorian antique furniture. And we found out everything about it. Victorian was a negative term at that time, and we wanted to support something that was discriminated against and despised. It's the same thing that we do in our pictures – we rescue something. It’s a rescue operation.

GOD GUARD THEE (2008) from the series JACK FREAK PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Do you collect other artists’ work?

In the beginning we did. For a very simple reason – very few artists sold anything. Then we felt we were different, we had a different vision of art. All those artists have an “art for art’s sake” vision, not art for life sake. We want to find a moral dimension in art – what is good and what is bad.

This ridiculous pursuit for purity in art, artists who ended up with black canvases or white…. Fruitless, empty formalism in art…. Art that is decorative, all abstract modern art, minimalist abstract, formalism – maybe it's easy to sell because it doesn’t say anything. Yes, we are very anti-that!

In 1971 and 1972 we talked about unhappiness, sex, drugs, drunkenness – they weren’t subjects in modern art that would sell; they were total taboos. They're still taboo. Many museums exhibit this kind of art in the basement because it's not real art. When people look at a modern work of art they say, “Oh, this is a good piece.” When they look at ours, they don’t say anything.

What is your relationship with art collectors?

British art collectors? They do not exist. We've never met one. It’s very interesting, because in the time of Charles I, in the 16th and 17th centuries, the English were the biggest collectors. They went to Italy and they came back with the most famous artists. Now, nearly 80% of all art dealers and collectors are Jewish. And gallery owners as well. With American or Italian roots, whatever.... It’s amazing! They have an interest.

That’s why it's very difficult to show in England – outside London – because if we do a show, they don’t collect. So it gets lost. At the same time, in Italy there are collectors in every little town, and they have a little gallery that tries to sell some art. Even when we had a LONDON PICTURES show in Naples, we sold there. In Naples, can you imagine?!

What is your relationship with curators? “Crucify a curator” is one of the lines in your works.

None. We are against them. Because they use the artist as material for their own vision. But we only want one-man shows with our own vision.

For years we were stopped by people on Brick Lane and they would introduce themselves with “I am a conceptualist from Bulgaria” or “I am a performance artist from Romania”.... They were all modern artists from some strange country. And then suddenly this changed. Now they are all curators! Extraordinary – they changed. Forty years later the Bulgarian conceptualist became a curator.

It’s a fashion. Even private galleries are using curators to do shows now. Sometimes they don’t even mention the artist, because they have the biggest curator. There's the title of the exhibition and the name of the curator. They have their subject, for example, the dog in art, and then they try to find twenty-five pictures of dogs in art. It’s like that in a way. We don’t like this; we do not want to be misrepresented like that.

GLEE (2013) from the series SCAPEGOATING PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

What is the most powerful force in the art world today?

We think museums are very powerful. There are more museums built now than in the last 100 years. Private and public. In England we have new museums all over the country.

Back in 1970, no one could name any living artist, nobody could do that. They could name a living murderer, living politicians, pop stars.... But now, if you ask people on the street, everyone knows the names of some living artists.

What are the rules you follow when making scale models for exhibitions?

It depends on how big the rooms are, how big the pictures are. The difference between us and the museum director or curator is that they design it how they like it, according to their own taste, while we design with the viewer in mind.

For example, this will be our first show in Tasmania – at the other end of the world. It is the least up-to-date place in existence, so… let the first picture in the hall be the most up-to-date!

It's all based on attacking the viewer.

From the first day in 1969, we had the idea of publicising our art, to make people come and to confront them. And we still have the same idea. Even when we design publicity posters or invitation cards – we want to seduce the viewer to come and see the show and after that to confront him with whatever we want.

We don’t wait for well done; we always go out there and do it by ourselves!

Do you feel support from the general public, and how do you feel they evaluate your art?

We have vast support from the general public, which is enormous personal strength to us. We can reach people.

In 2011 we were invited by collector John Kaldor to Australia to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Kaldor Public Art Projects with a series of talks and event. They asked whether we could do a signing. Yes, for sure! But there were no catalogues or posters. So they printed thousands of Valentine’s Day cards, and there was a queue of men, women and children without any sense of embarrassment – they were all standing there to get autographs from Gilbert & George. We signed them all!

FIGHT BACK (2014) from the series UTOPIAN PICTURES. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

You've been reprimanded that your art is unchanging, to which you've responded that only bad artists change. What do you mean by that?

When you look at Francis Bacon’s works, you could say they're all the same, look at Michelangelo and they're all the same, even Picasso – they're all roughly the same…. Only people who are not true to themselves, they change to a different style; their art changes to a totally different style because they are not sure of what they are doing. They try to fit into the modern art world, but the modern art world changes. So, they maybe do pop-art, and then they do minimalism, and then conceptual art – just to follow a trend. They try to fit into a system.

We don’t change, we evolve. The form of our art stays roughly the same, and we like our form, because we invented it. You can recognise our pictures even from a great distance. From 1971 onward, we've never followed the trend. Have we? But we have evolved like persons evolve. Years ago we were different persons.

We wondered why it took us forty years to do UTOPIAN PICTURES.... It’s strange in a way, but it took all that time.

We put a telephone box or a post box in UTOPIAN PICTURES. It's a great invention for us. Why did it take forty years to do that? We passed them every day, but we never thought to use one.

And post boxes – what stories they could tell? Extraordinary human stories! A telephone box? How many people have proposed in telephone boxes, how many people have sworn, threatened…. You could see people crying in telephone boxes! And now they are completely unused because of mobile phones. But not completely unused, as we discovered. They are used by rich criminals who cannot use their mobiles because they could be traced by the police.

This conversation took place in February, 2015.