The Freedom to Do Something That Makes “Not” Sense

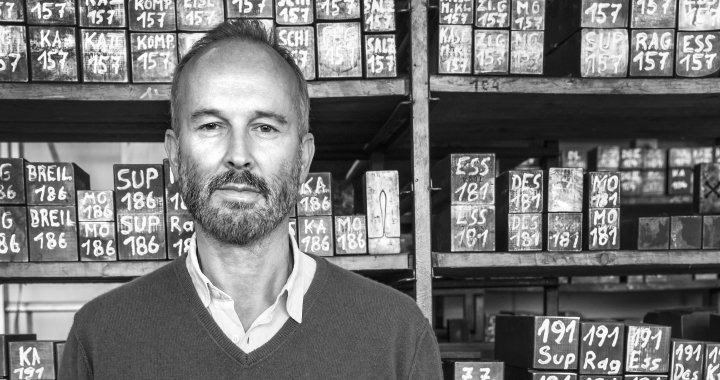

An interview with Austrian artist Erwin Wurm

04/08/2015

“The creation of an artist's world is always a struggle between freedom and restraint. To show things that at first seem pointless, useless – that is a way one can feel freedom...”. This is how the works of Erwin Wurm are described to me by Amer Abbas, curator of Erwin Wurm's solo show “Interpretation”. Going on through August 8 at the Vilnius art gallery VARTAI this exhibition of works by the famous Austrian artist lets the visitor experience (quite literally) Wurm's latest crop of objects, as well as individual trademark pieces such as the One Minute Sculptures – the series of grotesque, seemingly pointless works that brought Wurm wide recognition in the 1990s.

Not far from the VARTAI Gallery, at the Vilnius Contemporary Art Centre (CAC), another famous work by Wurm, Narrow House, is on view through August 9. The piece is a narrowed-down version of the artist's parents' house in which he grew up, and serves as a visual model of Austrian society in the period around 1950-1970: on the one hand, a still-living nostalgia for the monarchy; on the other, the deep-rooted influence of the Catholic Church. The way in which Narrow House has been displayed at CAC is different than in previous exhibitions of the piece, thereby giving it yet another way in which to be interpreted.

Erwin Wurm. Narrow House, 2010. Mixed media. 7 x 1,3 x 16 m

I meet with Wurm at Galerija VARTAI while staff is still working at getting the exhibition set up. Most of the pieces are already in place, but the curator and the gallery's staff are still rushing about, giving the whole scene a restless, pre-opening feel to it. Wurm himself seems unvexed by any pre-show jitters – every year he holds several solo shows at renown exhibition spaces the world over. Besides Vilnius, this year he has already shown at the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery in Salzburg, the Waldrieden Sculpture Park in Wuppertal, the Indianapolis Museum of Art in the USA, as well as at the Wolfsburg Art Museum in Germany and the Sara Hildén Art Museum in Tampere, Finland (the latter two are still showing through September). Waiting in line to host are New York's MoMA and London's Tate Modern, among others. Wurm is consistently listed among the top names in contemporary art. He's one of those artists whose works have powerfully influenced not only the work of other artists, but also pop culture: fashion photography, advertising, even music – in 2003 his One Minute Sculpture series was “acted out” in the Red Hot Chili Pepper's music video for the song “Can't Stop”.

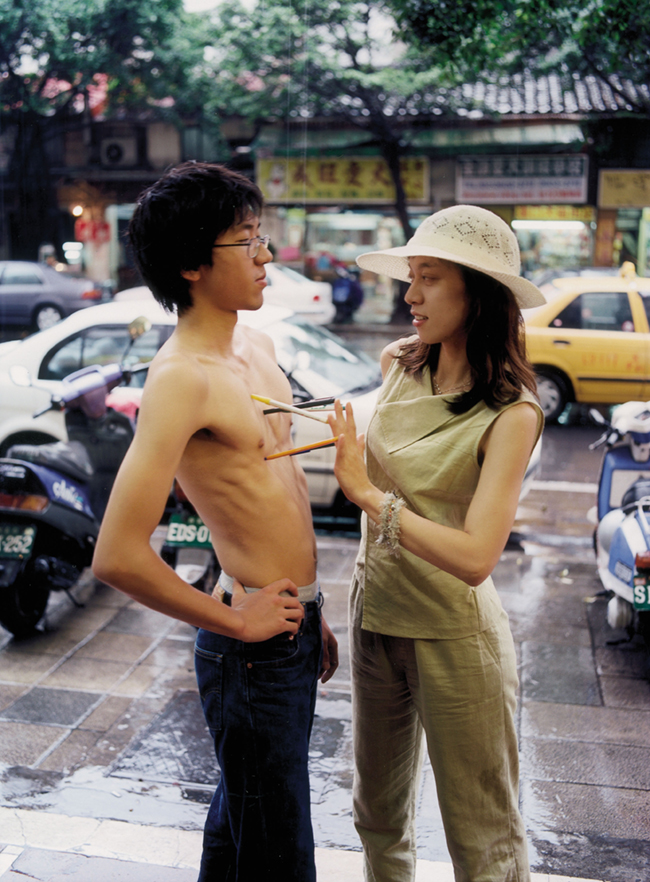

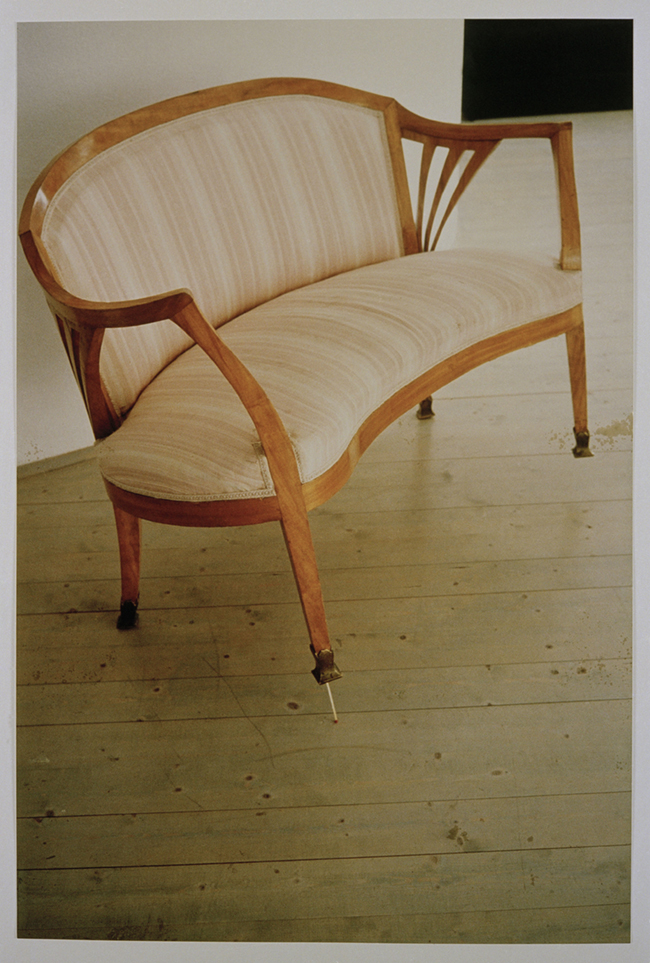

Erwin Wurm's art is characterized by the feeling that the world and the things that take place in the world are profoundly ephemeral and ambiguous. With his signature humor, and even a touch of cynicism, Wurm turns everything into a question, tearing down the borders between everyday objects and art, between the human body and sculpture. Fat cars; melted buildings; pencils and bananas that grow out of armpits and nostrils; a figure wearing layer after layer of sweaters; people who agree to do the strangest things so that they can become One Minute Sculptures – Erwin Wurm creates his own alternative world in order to escape the existing reality (if even for a moment). At the same time, his works bring up important issues and make us look at societal norms and prejudices from various perspectives, completely free of any pathos. Wurm's message comes at us in various levels – first, we notice the object's form and beautifully glossy outer layer; then, perhaps, we read into the various references and allusions to comic books, science fiction films, and philosophical works (e.g., Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein) that have been masterfully blended in with everyday situations; and then we continue on, discovering ever deeper truths about the world and human existence. It seems that Wurm can turn any thing, any feeling, into sculpture.

Erwin Wurm. Outdoor Sculpture Taipei, 2000. C-print. 159,1 x 126,5 cm

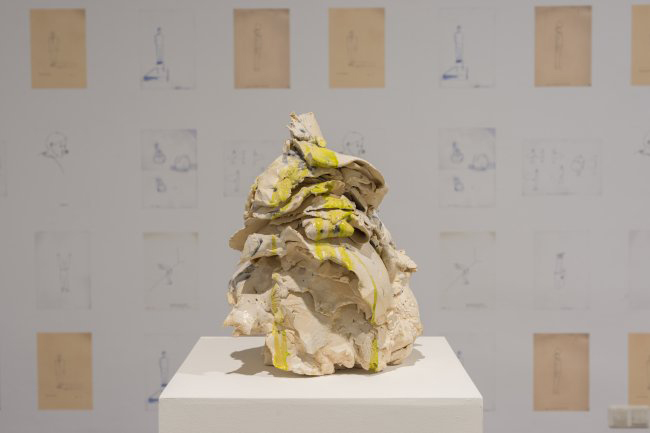

A certain system emerges in the exhibition “Interpretation” – three of the gallery's rooms feature video works in combination with photographs of One Minute Sculptures, along with the various simple objects required so that each member of the public (and this is an important part), following the instructions provided, can experience a One Minute Sculpture in real life. The fourth room is devoted to Wurm's latest works – ceramic objects accompanied by copies of Wurm's illustrative instructions lining the walls like a kind of wallpaper. Curator Amer Abbas explains that the idea for the exhibition came about through his and Wurm's discussions on the aspects of freedom and the ephemeral when pondering the meaning and influence of time. In further developing the concept of being-in-the-moment, as found in Wurm's works, Abbas has come up with the hypothesis that “interpretation is a part of the creative process in making a work of art. It is not just placed in the hands of the critics or viewers; it is already enacted in the artwork itself and thereby becomes another expression of freedom.”

Erwin Wurm. One Minute Sculptures, 1997. C-print. 45 x 30 cm

What is your interpretation of the exhibition?

No interpretation.

No interpretation?

No, because curators can interpret; artists make the work.

The curator told me that when an artist makes a work, he is also interpreting.

The artwork is an interpretation of the world.

In your interviews you have said that you are interested in everyday life. Are you just observing it or is it important to ask questions?

For me to work on the sculpture means to ask questions about social issues. Not only artistic balance questions, like three dimensionality or time, but also questions related to the social issues. For example, if we gain weight or loose weight, do we add volume or do we give volume away? One could say – gaining or loosing weight is a sculptural work. Nowadays society is totally slim-focused. In America the rich people are the slim ones, and this claim becomes a very dramatic social question in terms of those who cannot afford to be slim – because they don’t have an education, they haven't achieved a certain level of livelihood, and as a result, they can afford only cheep food that makes them obese.

That’s how the Fat Car and the Fat House came into my art. Fat Car is a combination of the mechanical system of a car and the biological system – these two things normally don't go together, but they will in the future. I’m convinced ever more about this from the literature that I read, as well as by my friends who work in the sciences. In the ‘70s there were cars – Bonzenkarre – for bad rich people (Bonzen means “the bad rich ones”). I tried to realize this idea of fat car, showing all of the damage done to it, by creating the effect that it has become human. The cars and the houses are objects from daily life, and also status symbols.

Erwin Wurm. Fat Convertible, 2005. Mixed media. 130 x 469 x 234 cm

So, is it a critique of consumer society?

It's just an observation of how our society moves slowly from “to be” towards “to have”, and now it has become more important than ever.

Does this bother you?

No, I watch it, and I work with it.

... and you forget about it?

No. It is an interesting fact for me. Another interesting fact is how our society moves backwards – away from enlightenment philosophically and politically, and away from the achievements of the Western world. The patriarchalistic structures in religion and politics come back. It's interesting to think about how things are going to be.

Do you like the world you live in?

Partly. Not totally.

What would be the perfect or ideal world for you?

More freedom, more tolerance, less orthodox structures coming back in politics and relations, more enlightenment; yes – more freedom.

Do you yourself feel freedom, as an artist?

I found that to be an artist and to make artistic works means to create “not” sense for the world. For example, a policeman, a teacher, a journalist, a farmer etc. – they create sense, they are an important part of society. Whereas art, in its foremost meaning, doesn’t create sense; it's a space free from sense, and I found this so interesting, so challenging. Like playing soccer – there are people who make a living from playing soccer; they don’t create sense, they create something senseless, but that creates freedom, and this is so important from my point of view.

While the rest are looking for meaning, art has the ability to free the world of sense in the first hand.

But for that you would need a certain background, wouldn’t you? Why do you think most people are not free?

Our society is constructed in a way that there is not much freedom possible. We all are stuck in different relationships, in different conditions, obligations, and everybody has to function in a certain way; otherwise our society doesn’t exist, it doesn’t function. And, not to be a part of this all of the time, is a part of freedom. It's only partial, very partial participation. For me, developing this work (points towards his ceramic works – Not titled yet, 2015) is a try.

Ewin Wurm. Not titled yet, 2015. 40 x 29 x 33 cm. Photo: Arnas Anskaitis

And these ceramics are very new works?

Yes. Ceramics – it could also be another material, but this is just easier. If I did it in another material, I'd have to cast it, and that is much more complicated. This way it is more direct.

Is this also about freedom?

Yes, it is about the freedom of artistic choice. I am an artist who has many shows, and there are collectors who always ask me to do the same things all the time. I like to disturb this idea and to do something else. I've done this several times during my life, in my work. They always come and say, ‘Oh, well! Aha! Interesting... but do you still have the other work you did two years ago?’ I say, ‘No,’ but then in two years they will come and say, ‘Oh, that was interesting – the work that you did previously, do you still have it?’

I don’t even know if it's good or not (points towards a piece in ceramics); it's interesting for me. It is an exercise of freedom for me.

Erwin Wurms. One Minute Sculptures, 1997. C-print. 45 x 30 cm

And who do you think rules the art world – artists, curators, dealers?

Nowadays it is pretty much a divided world; in the ‘70s it was more or less a closer world. One world is the big galleries; then next comes the world of auction houses. You can see how some artists have come back through the auction houses with enormous prices. And then the third world is biennales and “documentas”, and curators. Every world is a little bit connected to the next world. And there is also the world of big collectors, which is interrelated in between everything. Sometimes I have a feeling – when I’m dealing with one world, the other world doesn’t exist. And vice versa.

Do you think about those worlds when you make an artwork?

No. Definitely not. That is also about freedom – when I created the One Minute Sculptures many years ago, all of a sudden it was going very well; the interest increased and the galleries wanted to do me more and more pictures, but I stopped; and I didn‘t take photographs for twelve years, so the interest faded. And now all of this has come back in a big wave! The Tate Modern wants to make a show with the One Minute Sculptures, as does the New York Museum of Modern Art and others. By resisting, not producing too much for the galleries, it came back from another area. And now we will see what will happen with this (ceramic sculptures – red.). Nobody wants this at the moment. (Smiles.)

But my freedom is not to be dependent on selling these things, because I have sold many things and I can slow down. I can do what I really want and what I really like.

Erwin Wurm. Untitled, 1983/1984. Wood, paint. Photo: Studio Wurm

Did you think the same way about these questions before that turning point in the early 1990s when you replaced your Dust Sculptures with the One Minute Sculptures, which then became a success?

I think so, because when I started to do my first pieces in the late '70s / beginning of '80s, it was the time of minimal art, conceptual art, pop art, soc-realism, and so on. I was studying at that time. I read somewhere: if you want to be successful in life, you have forget your “father's ideas”. So I thought – OK, I’m not going to make minimal art or conceptual art; I will try to do something else. And I found wooden boards and nailed them together as classical sculptures – very wild, very strange – and painted them. I had some success with them in Austria, in Germany, but then I realized rather quickly that the core of the work was a reaction to, and negotiation of, a certain understanding of art. And I thought – this cannot be the basis of an artistic life – so I moved back! I had collectors, I had critics who liked the works, the galleries who showed me, but I moved back, totally back – I went back to the Dust Sculptures. Everybody was shocked, everybody hated me, everybody kicked me out of the galleries. (Laughs.) But I thought it was so important.

The guy is still whistling... (Looks towards the video.)

Erwin Wurms. Blow Job I, 2007. Video still. 5’43”

In this exhibition we see three video works. In two of them you show a whistling man. Are these two videos having a conversation with one other?

There are two videos (Blow Job I, Blow Job II, 2007 – red.) that should be played at the same time.

The videos are related to the play “Hamlet”, as performed in Schauspielhaus Zürich. In 2007 I was invited by the theatre to make a work on Shakepeare‘s “Hamlet”. The guy is whistling in slow motion with a whistle in his nostrils or mouth, and this aggressive loud noise – which is normally very annoying – turns into this kind of sound that hypnotizes people; it goes inside the heart because of the slow motion. For me, it is interesting what one can do to learn how to manage one's breath, to control the body, to control the mind, to control the speech, and everything else that is related.

When I sat there it was like doing meditation, but nevertheless, I felt as if the guy was coming across as very desperate.

Yes, because he had a task – the task to whistle; to do it in front of the camera. And he didn’t know if this is a smart thing to do or not. (Laughs.) So, he just did it. This is actually a Swiss actor (Mike Müller – red.) from the very famous Schauspielhaus, and I think he totally is not sure what he is doing there.

Wasn’t he told to try and look desperate?

No, I don't give comments on how people should look. Never! I wanted him to do the work seriously, and not laugh and giggle around. But it is very much about pain, in a way. Pain is an important part of us. Normally we don’t want pain. And also about the feeling of being marginal, the feeling of being totally unimportant, the feeling of being ridiculous, the feeling of being bad, stupid, not smart – it is constantly with us. That‘s what my works are about. Sometimes it's me who is stupid, sometimes the others; sometimes I persuade people to act stupid. Accepting stupidity, in a way, also gives us freedom.

Erwin Wurm. Outdoor sculpture Self-Service, 1997. C-print. 120 x 80 cm

To accept your own stupidity or the stupidity of others?

Your own stupidity! What's so fascinating for me is this – I am the centre of my world, of course, and you are the centre of your world, and he is the centre of his world, so each of us is the centre of the universe... We are 7 billion people and everybody thinks that he is his own centre of the universe! It's ridiculous! Obviously, it's also stupid. I think that having a more distant relationship with our thinking of ourselves as being so important – learning and accepting the world in a not-so-self-centered way – would make our life much easier.

And the third video?

It's about the breathing practice used in theatre and also in yoga. This guy is really hypnotized here. Not me, someone else did that. He was hypnotized for 10 hours; the one doing the hypnotizing is talking, and the hypnotized guy is just standing quiet. There is another version of the video where another guy is hypnotized for 14 hours; it takes place outside in the countryside – from sunrise to sunset.

For me the question was – is it a sculpture or is it an action? When I started to make works about the motion of a sculpture, the first question was – when we are standing, what is it? A sculpture or an action? Can it become a sculpture if I stand long enough? Or if I slow down a movement so that it becomes really, really slow motion – is it then a sculpture or is it an action?

Did you find an answer?

The balance is somewhere in between. What I’ve realized is – I made a video once with the person standing still for one minute, nearly not moving; then I looped it for one hour, for a show – our brain is not constructed to see the quietness, so the imagination of movement was projected – people saw movement.

We tried to find different people who could do this. Some twenty called and we chose two persons who said – I can do this, it's not difficult at all. One of them gave up after one hour, although he was a very quiet guy. 10 hours is very long.

(Looks towards the ceramic sculptures again.) I think this sculpture is quite good. I’m happy with this one.

Erwin Wurm. Photo: Inge Prader