Exploring Public Cyber Spaces

An interview with Estonian artist Ivar Veermäe

Sheena Malone

08/10/2015

Autumn holds a busy schedule for Estonian artist Ivar Veermäe. Over the forthcoming months, his work will be on view in “Operation Mindfuck” at the Kunstverein Wolfsburg, Germany; at the Noorderlicht International Photofestival 2015, The Netherlands; and at the Belo Horizonte’s International Festival of Photography, Brazil – all this exposure coming in the wake of a nomination for the prestigious Köler Prize earlier this year.

Veermäe’s research-based approach explores notions of public space (whether it be physical urban space or cyberspace), networks, new media and group behaviour. His interest in new technologies has led to the creation of several projects with a focus on data centres and their physical presence – something we often forget in an era of wireless connections and cloud computing. His long-term research project, “Center of Doubt”, explores and visualizes the disappearance and reappearance of network technology, its infrastructure, and representation. Contrarily, for another project, “Relational Uncertainty”, Veermäe brought a cyber-world into the gallery space.

We catch up with Ivar Veermäe in Berlin, where he currently resides, to chat about living and working between two countries, his practice, and his plans for the future.

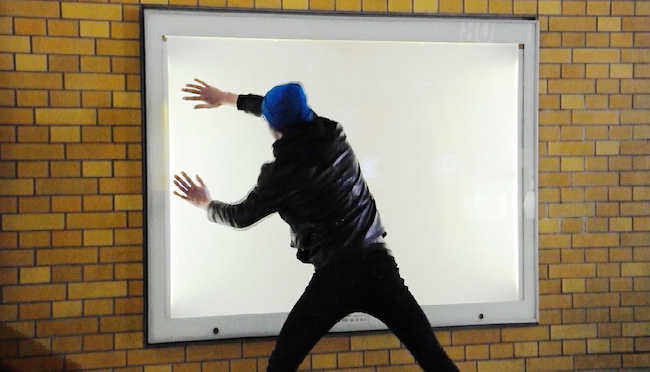

It / The Future is Bright. Installation with sound, 2012

I read that you studied at the Weissensee Kunsthochschule, where you completed a MA in Spatial Strategies. How long have you been living here, and what is it that keeps you here?

It's been seven years already. Actually, I just happened to stay in Berlin. Before, I was in Essen with the Erasmus program. It is a totally different place. But I was there for a shorter time, and it is also somehow interesting. And Berlin – well, quite a lot is happening here, and I'm staying also because of my girlfriend and other friends. In general, I like the city, but I do visit Estonia quite often, which is a good break from Berlin.

Just recently, The Guardian newspaper ran an article on how young British people working in the creative industries are leaving London for Berlin. Since moving here, I have found that it seems like everyone passes through here at some stage. Do you feel that Berlin still offers opportunities for artists that other cities or art scenes do not, or cannot?

I can compare only the art scenes of Estonia and Berlin, which are really different. Both have their good and bad sides. For example, it is much easier to organize an exhibition in Tallinn, Estonia. Another difference is that, in Tallinn, there are not so many exhibition spaces as in Berlin, which means that they have quite high visitor numbers.

It is good to live and meet people in Berlin, but it's more difficult to make an exhibition intended for more than just your own friends. It is nice to make such smaller exhibitions sometimes, but it would be good if also other people could see the work. Therefore, oftentimes in Berlin group exhibitions make more sense. Of course, this does not apply to the really big names – their exhibitions get high numbers of visitors. I still make exhibitions in Berlin, but I'd say that here, it is better to go to others' exhibitions than to make one by yourself.

iTouch. Video 03:35 min / 3 screen installation / performance, 2012

According to your exhibition history, you are very active in both the German and the Estonian art scenes. Can you tell us a little about your work? Do you feel that a difference in location between Berlin and Tallinn has had an impact on your work or on the themes that you explore? Or, would you make the same work no matter where you were based?

The real, existing location is really important in most of my works. I often make research-based works, and for me it is important to go to the places where the researched topic is located. Berlin played a big role in my earlier works about demonstrations because Estonia is mostly a non-demonstrating country. Back then, I found the demonstration-culture in Berlin really interesting. I participated in many different demonstrations, and I also filmed and photographed some of them. There is an interesting group feeling at these events.

But now, most of my objects of interest are located outside of Berlin. This year I have been to many places in Germany – for example, Frankfurt; a small place called Biere, where Deutsche Telekom has its most important data centre; Bad Aibling in Bayern, where the SIGINT station of the BND is; and Brocken, at a former signal station for the Stasi and the GRU – the Russian signal intelligence service. In Berlin, I process the collected material. I think that mentally, the place also influences my work, and it might be that I would make a different kind of work if I lived somewhere else.

Crystal Computing (Google Inc., St. Ghislain). Video, FullHD, 14:47 min, 2013

You mentioned that your interest in the public space began when you were in the Erasmus program, in Essen, which is where you experienced some public demonstrations in the public sphere. What was it about this experience that struck a chord with you?

As I said before – the group feeling is kind of an interesting thing for me. I, myself, am not so much into group things (group games, group sport etc.), but I find it interesting to participate in these events as a kind of alien. But sometimes, I have gotten into this group feeling; for example, a few times on the first of May, when quite a lot was happening, and you have to decide really quickly what to do, where to move next – this is all very much influenced by the group.

In Essen, I had not yet started to participate in demonstrations; that happened a little later, in Berlin. In Essen I found something that seemed quite interesting – there was a sticker-and-graffiti-war between Antifa and Anti-Antifa going on. The interesting notion there was the fact that the opposing groups had an almost identical style in their designs. Also, a similar slogan structure; the only thing that differed is that their ideas are totally opposite.

Back then I was interested more in group dynamics and now I can say that of course demonstrating makes sense by often bringing important issues forth. It is like giving abstract ideas a body, which represents them more directly – through voice, clothing, flags, and banners. And then, as always happens with representations, they can never be totally direct, something other happens in real life. This kind of search for this “other” is important in my work.

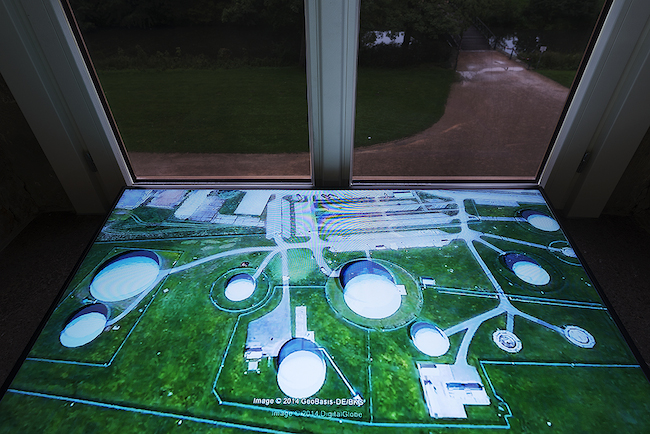

Echelon, 2015

Then you began to investigate the impact of the public space and cyberspace. Was your “Personal Record” collaboration with Karol Komplimets the beginning of these investigations? For the project, you looked at the blurring of the boundaries between public/private and personal/collective, and your interest lay in how willing people were to share their private data in real life. What did your investigations reveal?

Well, the first project with Karel Koplimets was “Don´t Be Evil”, in which we created our own version of Google Street View in Tallinn. We photographed the real places, and afterwards, digitally erased all advertising spaces. It was a time when there was no street view of Tallinn, but Google's cars were already photographing the streets. Our aim was to concentrate on the public space, and the removal of advertisements was a reference to Google's model – most of their income comes from advertising.

The second project we did together was “Personal Record” in Tartu, in which we used the ten profile questions from Facebook and went into the streets trying to interview people. It went actually quite well, and many people agreed to answer our questions. We recorded the answers as audio. These answers became more personal because they were answered in the voices of the real people. On Facebook they are used as keywords for targeted advertising; there's not that much personal about them. Additionally, we went to different places – the city government (where we interviewed the mayor of Tartu), the University, McDonalds, supermarkets, etc. These places are semi-public, and it was an attempt to see how accessible they are – and they actually were. It is a common thing that in private places – supermarkets, for example – there are many things that are not allowed, such as filming, etc, but it is not really enforced, and if you want to, you can usually get around it.

Center of Doubt, 2012 - 2015

Recently you had a solo exhibition at the Edith Russ Haus, in Oldenburg, in which you showed “Center of Doubt”, a project that you had been working on from 2012-2015. As part of the research process, the project and te results change over time. What was the initial aim of “Center of Doubt”? Did the results match your initial aim?

This is the longest project I have ever made. In the beginning, I had no clear results in mind; I just wanted to find out more about data centres. I located most of them in Berlin, then went on to Belgium, where Google's biggest data centre is located. There are so many issues connected to this theme, and the project changed constantly. It had some fixed points – or works ready – but actually, now, when it is “officially finished” for me, I still cannot finish it; and when I´m showing it somewhere, I make some changes or totally new additions – as I did now, for the exhibition “Operation Mindfuck”, in Wolfsburg.

But in general – when I´m making a long-term project – I want to know more about some issues; and by researching them, I would collect and create lots of different material, and some of it is in a form for showing it to other people. When I show it in the exhibition, it should also function spatially. For example, for the exhibition in Wolfsburg I will show the original Channel 4 video “Echelon” (now Channel 5), on the windowsills with the windows darkened. So you can see the satellite landscape in the video, but also a darkened landscape of the castle´s garden. The exhibition is in the castle, where Kunstverein Wolfsburg is located.

Center of Doubt, 2012 - 2015

“Center of Doubt” will also be shown at the Noorderlicht festival. Will the piece manifest in a different way?

In Noorderlicht, three videos of the project will be shown, so it is a part of a bigger story. It is not so different, but as I mentioned with Wolfsburg, I´m showing one part of “Center of Doubt” accompanied by a new work.

Originally, my video work “Echelon” was about the SIGINT network between the US, the UK, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. It shows, through satellite images, the various stations. But this would be a one-sided view, therefore I had to add a new video that shows Chinese and Russian signal-stations.

Additionally, I made an entirely new video for the exhibition in Wolfsburg, one which deals with the history of signal stations and with their origins. For example, the first object in space (the boundary between the Earth´s atmosphere and outer space) was Vergeltungswaffe 2, a German Second World War “Vengeance Weapon”. After that came the first satellites and everything else – the V2 made the way for them. The first satellite networks allowed for satellite communication and also the interception of signals, which was the start of the satellite SIGINT stations. So, with this part of the work I want to show that the NSA activities, which came very suddenly into the light, have a long technical past that allowed for it all to happen.

Congratulations on being nominated for the Köler Prize earlier this year! For the exhibition, you showed “Crystal Computing (Google Inc., St. Ghislain)” which incorporated a mix of video and documents. For your initial plan, you had hoped to gain access to the plant and film inside, but you were refused permission. How did you get around this limitation?

Thank you. I tried to get official access to the data centre, which was not granted. All they did was write a letter saying that they have a really nice website on their [Google's] data centres, and that I can find all the information on there. It is a nice website with really nice images, but I was interested what the data centre “really” looks like. So, I made a trip to St. Ghislain, Belgium, and filmed for four days outside the fence of the data centre. The place is quite well protected. In addition to a huge amount of security cameras, the security service makes a round of the building every 30 minutes or so, but I found a place with bushes, trees and farmland, and most of the material is filmed from there.

Apple Black Box

The outcome is a video in which colossal clouds of steam can be seen because of the water cooling sytems; it's reminiscent of the old images of factories, but as I said, it is a new factory. In the video I give most of the importance to the object – a big box – the data centre and its environment and other details.

The work shown in the Köler Prize exhibition was accompanied by another video that deals with Google's tax evasion tricks. Additionally, I have the original documents printed on transparent pvc sheets, where I have highlighted and bluntly translated something from the original text in French, which I do not speak, through Google Translate. The documents are an interesting example because the representatives and sums of money are constantly changing. Also, the company’s name is in the first document, “Crystal Computing”, but only later is Google mentioned. The data centre in Belgium also had no sign indicating that it was Google, just Crystal Computing.

Don´t be evil with Karel Koplimets. Interactive net-based installation, 2011

Data centres feature repeatedly in your investigations. We are so used to the notions of wireless and cloud computing that the regular user sometimes forgets that these physical places exist. What is the importance of them in your work? Inside, are they uniform in their construction and interiors?

The data centres are, in general, more or less uniform on the inside, but the buildings differ. For example, the smaller data centres in cities are often located in older buildings, where the only sign of it being a data centre are the cooling boxes on the roof of the buildings. But really big data centres are big boxes, quite similar to logistics buildings. It is a new industry; for example, at the opening of Deutsche Telekom's data centre, it was titled as Industry 4.0. It is an interesting notion; it removes humans from the process. For example, already in 2008 there were more things connected to the internet than humans. It is an interesting stat because the only possibility of connecting to the internet is through things. But according to some forecasts, in 2020, Internet-connected things will reach 50 billion. So, the data industry has pretty much established itself – mentally, technically, and economically. My actions would change nothing directly, but I find it still important to doubt these issues, to show the industrial backgrounds and not just use everything that is simple and easy-to-use.

Ivar Veermäe. Photo: Kristina Õllek

Where can we see your work in the near future? Are there any other projects that you are working on that we can anticipate?

I will be showing ”Center of Doubt” in November – and again, in a different form – in the ”Monitoring” exhibition in Kassel, a part of the Kasseler Dokfest. After that, I will have a solo exhibition at Galerie im Turm, in Berlin, at the end of the year. It is the start of a new long-term project about financial escape – firstly, about tax havens; secondly, about logistics, flags-of-convenience and so on. But it is a little early to speak about it yet.