A Way to Be Happy

An interview with German painter Norbert Bisky

22/08/2016

Norbert Bisky is a German painter based in Berlin. Even upon first sight, his paintings are imprinted in one’s mind as exuberant, colourful, image-laden works. When speaking about his early works, influences of East German social-realism aesthetics are usually mentioned – serving as inspiration were memories of his childhood in East Germany, images from children’s books and Pioneer posters, as well as from socialist propaganda ephemera. However, in recent years he has shifted to darker themes – of disaster, disease and decapitation – all the while retaining a consummate painterliness that is the hallmark of his work. All of this Bisky then intertwines with Christian ideology, art history, gay culture, pornography, and apocalyptic visions. His figures, in many cases, are floating, falling or tumbling, without any gravitational axis.

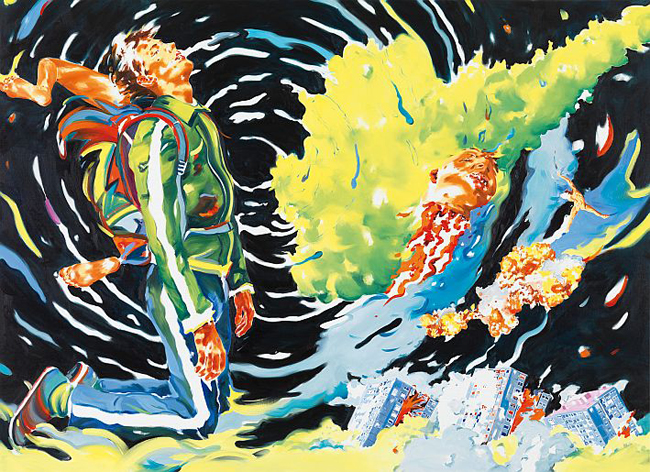

Norbert Bisky. Übergepäck (“Excess Luggage”), 2008. Publicity image of LNMM

One of Bisky’s works – the painting Übergepäck (“Excess Luggage”) – could be seen in Riga as part of the exhibition “Elective Affinities: German Art Since the Late 1960s”; this was the largest exhibition of German art in Riga since the early 1990s, which saw the exhibition “Interferences – West Berlin Art, 1960-1990”. At the press conference for this latest exhibition, Bisky revealed that “Excess Luggage” is special because it was created eight years ago, at which time he was confronted with a lot of tough issues like loss of security and terrorism. As you shall read in the interview, Bisky references the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, to which he was a witness – his friends were staying in one of the hotels that was attacked. The incident severely impacted Bisky’s life view, and consequently, influenced his art as well. When speaking about his sources of inspiration, Bisky says that the largest influence of all is life itself: “Everything that I see – that attracts my attention – inspires me. I use a lot of the photos that I take with my phone camera, and even make entire exhibitions around them. Sometimes, as a starting point, I take existing images that someone else has made. The material is a very inspirational factor as well – a couple of years ago, I started to work with oil on paper in a very liquid way; making the oil painting as liquid as possible changed the entire process of my painting, and it also changed how the paintings look right now.

“And there is one more important thing: in my paintings, I tend to talk about things that I have a personal relation to. There must always be an autobiographical element in it – otherwise, I don’t touch it. That is very important for me.”

In Berlin’s art scene, one doesn’t see a lot of paintings nowadays – most artists express themselves through other media. Why have you chosen to paint?

My motivation to paint changes all the time. It is like a habit for me now, but I decided to be a painter when I was in my early twenties. It was after the Berlin Wall came down, and for me – for a person who grew up in a very closed country like East Germany – it was like an explosion of possibilities, like winning the lottery. Suddenly, I found myself in a situation in which I could do whatever I wanted to, but which also meant that a certain kind of stress arose – you have to ask yourself what is it that you really want to do with your life. It took me a few months to think about it, and I came up with the idea that I really want to do paintings because I really enjoy the process of creating them. I understood that it probably won’t be possible to make a living from it, but if it makes me so happy – I want to do it. There are just a very few things that make me as happy as painting.

It is a great way for me to express myself. I go to my studio, I’m on my own, and I just paint. Right now it is like the centre of my life. It is my life! It is hard to describe it without getting completely kitschy, but the main life energy that I have, goes into my painting. I’m trying to put my life into it as well. And I try to be honest and serious, and funny, silly, stupid, everything... Sometimes that works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

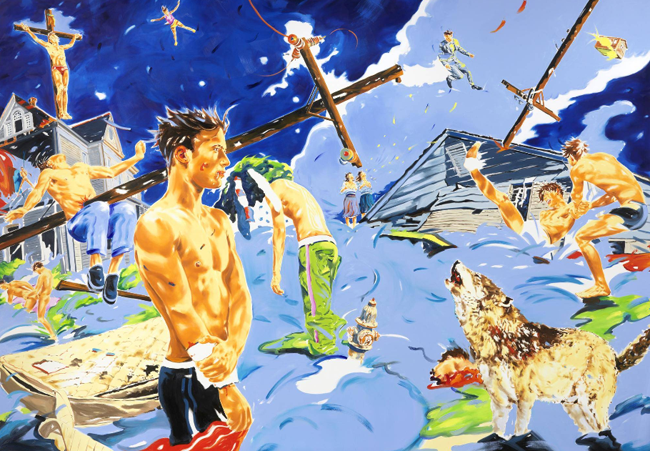

Norbert Bisky. Hérésie, 2015. Galerie Daniel Templon, Brussels. Exposition view. Photo: Bernd Borchardt © VG Bild Kunst

When doesn’t it work?

That has to do with the practical side of the process – the material has certain limits. When I reach them [these limits], which sometimes happens at 4:30 AM, I realise that I just fucked up the painting. So, I have to take a knife and destroy it. And that’s what I do.

Does this happen often?

Fortunately, it doesn’t happen very often – believe me, I have a hard time when I have to destroy a painting after having spent days and weeks working on it. But it happens every year.

So, you turned to painting when you were already studying art.

No, I was doing regular crazy jobs – like working as a waiter, taking care of old people in an ambulance service, etc. Then I went to university to study art history and the German language and literature. I didn’t like my studies much, so I went to the lady at the students’ office and said: “You know, instead of sitting and looking at poor-quality black-and-white slides of great masterpieces, I would prefer to make my own painting, even if it is shitty.” And the lady told me: “You have to take care that you don’t go crazy.” She warned me that I should stay “down to earth”, and not become a megalomaniac. After this conversation, I was pretty sure that I actually should go crazy and become a painter. So, I entered the Art Academy and studied there for five years. I was on the right track.

Norbert Bisky. Aquageddon, 2007. Photo: Bernd Borchardt © VG Bild Kunst

You were a student of Georg Baselitz. How much did he influence you? How would you describe his impact on your artistic approach?

He was a very important influence for me, although I never wanted to paint like him. It was clear from the beginning that I was interested in different things than Mr. Baselitz was. But it was a great situation – to have someone there who really has a clue about what he is talking about, someone you can highly respect. It was a great dialogue, but always with a certain distantness – because I wasn’t a fan. We had a really interesting conversation for five years – about what I would do or what I could do, or should do, or was doing. It was very important for me.

Did he show you the direction to take?

Basically, it was the other way around. He stopped me when I was on the wrong road. He would say: “No, that’s shit! Don’t! You cannot continue this way.” I think you need somebody like that when you are trying to find your way. Without him, I would have done completely different stuff. He opened up some possibilities to me because he thought big – for instance, he invited us to his exhibition opening at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, in 1995. As a young art student, you are impressed by this, and you see what is possible. A very different scenario from the one you see when you try to rent an apartment and everyone is telling you: “Oh, you are an artist! A poor person... How can you make a living from it? My condolences...” Maybe it has changed now, but back then, the value of being an artist wasn’t all that big in Berlin. Meeting Mr. Baselitz provided me a way to see what is really possible.

Norbert Bisky. Balagan, 2015. Bötzow Berlin. Exposition view. Photo: Bernd Borchardt © VG Bild Kunst

Can you imagine: if you weren’t a painter, what would you be doing instead?

Something else, and being happy...? I don’t know. I just chose the profession that’s right for me.

You are one of those lucky people who have chosen the right thing to do.

Yes, I have had a lot of lucky breaks in my life. I’m lucky, but I try to make something out of it; I’m aware of my luckiness. I think a lot of people are not aware of their good fortune. I was a professor at the Art Academy of Geneva, and so many of my Swiss students said that they are having a really tough time, that they have such a hard life – they have no options, they don’t know what to do, and where to go... And so I told them: “Hey, listen! You are in Switzerland! You are the lucky ones!” I think that basically, in all of Europe, we are the ones who are kind of privileged, although maybe on a different level. For instance, if we compare ourselves to people in South America – I have met so many interesting, good-looking, smart people there who really don’t have any options – they cannot move, they cannot go elsewhere.

Norbert Bisky. besetzt, 2007. Photo: Bernd Borchardt © VG Bild Kunst

Do you remember what was the turning point in your career – at what point you evolved from being just an artist who paints in his studio, to an artist who is highly sought after by galleries and museums?

It was a very simple moment – a gallerist came to my studio and said: “Let’s work together; let’s prepare an exhibition and hope for a lucky chance to sell at the exhibition.” At that moment, I realised that things were now different. At the beginning, I was very excited about it – it was really new to me. I was trying to manage not losing the situation, and that was stupid. [Laughs] So, it took me some time to learn that, even if you find yourself in a lucky situation, there is no way to hold on to it. You can try, but not by being scared of losing something. For example, I found it very depressing when the art dealer told me: “I have a waiting list with 200 names on it.” So, I stopped working with him, and as I left the gallery, I said to myself: “It’s my life, let’s make paintings that look completely different.” So I did – I changed my style, and I tried to regain my freedom by not being imprisoned by demands or the expectations of other people. That was a difficult situation I was in, 15 years ago. Now I’m in a happy situation – even my collectors don’t know what I’m going to do next, but they are getting used to it, and that gives me a lot of pleasure.

Norbert Bisky. Zentrifuge, 2014. Kunsthalle Rostock. In collaboration with Henrik Schwarz. Installation view. Photo: Bernd Borchardt © VG Bild Kunst

So you don’t follow somebody else’s expectations, you just follow your own.

I remember the exhibition I had five years ago – there were a lot of collectors who came to the opening, and they were pissed-off because they didn’t find what they were looking for. But at the time, there were some collectors who said: “Oh, it looks strange, but somehow, interesting.” So I started new dialogues. I also met new people who said: “I didn’t like what you were doing before, but now – this is interesting.” It is an ongoing process. And it is a tricky game... I think the demanding situations that collectors create could actually kill an artist. For me, it was like – Ah! I cannot! It’s strangling me... Maybe other people can handle it better. I try to be alive, I try to change, and I try to do what I want. Sometimes it matches the expectations of the people, and sometimes it doesn’t. That’s life.

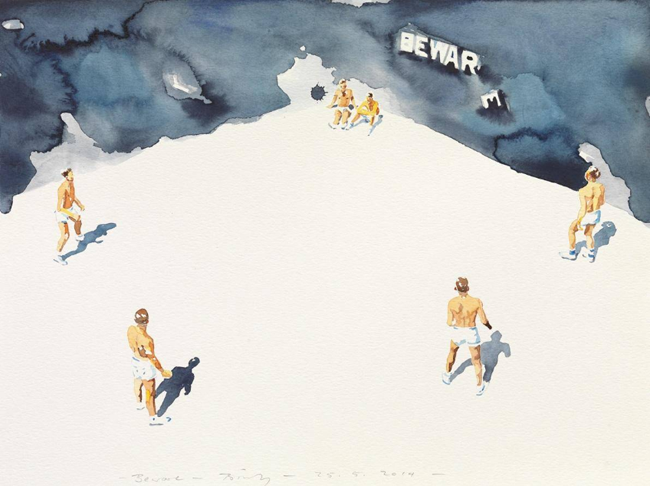

Norbert Bisky. Beware, 2014. Photo: Bernd Borchardt © VG Bild Kunst

What bothers you in the world today?

There are so many things... Going back to the 90s, there were some minor problems, but basically, the atmosphere was like – happy, peace, harmony, love, having fun. I think it is a completely different time now; a lot of people are very scared. What bothers me the most is the fear. I think it is a starting point for a lot of strange, difficult and dangerous things. They always start with fear.

For instance, last year I lived in Tel Aviv for a few months. It was a life-changing experience because I realised that the conflicts that are going on there are not easy to solve. However, I met a lot of great people there who are bursting with life-energy, trying to enjoy the moment – which is very precious. That helped me to change my perspective on certain things.

Another situation that changed my perspective and showed me how precious life is – and how it can completely change in a second – happened to me in 2008, when I was in Mumbai during the terror attacks on the Taj Hotel. Before that, I saw terrorism as something bad, but as something that doesn’t affect me – it was like watching images of fire on TV. And there I was, right in the middle of it – my gallerist was taken hostage, and although I was very near to the area, luckily enough, I was not in the hotel at that moment.

Nowadays we don’t need to go to Mumbai – these kinds of things are already taking place right here, in Europe.

In Germany, there are a lot of people that still live in a certain bubble – they think they can stay away from the trouble. That also bothers me. I think the world is so very connected now that problems create effects everywhere.

Norbert Bisky. Diaspora, 2016. Photo: Bernd Borchardt © VG Bild Kunst

Do you see how you, as an artist, can impact this situation?

I’m not sure if I can impact it. Sometimes I try to. For instance, some of my friends and I help out the refugees who have arrived in Berlin over the last year. In a way, it is becoming a part of my artistic work – it also goes into my paintings. However, I think my job is to be sensitive and to notice things, and to then put them into my works. Perhaps it is like a message in a bottle – a message for the future. That’s an idea that I’m currently working on – I want to put my perspective of our time into the paintings, because most of the messages that we share on the Internet or through our phones will disappear. Painting is slow, but it also lasts longer.

Have you ever thought about what matters most to you in your life?

Hmm... I think – definitely living in the moment, noticing the moment, which is not very common these days because almost all of us are distracted by our smart phones. We are in one place, but we are also in ten other places at the same time. I’m trying to really “be in the moment”. In my thirties, I had the following perspective: it’s a party, it is going to last forever; now, I have a certain sensitivity in terms of the things that I now know: soon, everything will disappear, including myself. So, I’m trying to be awake, to get as much as I can from my surroundings. And a very simple thing: being in the studio and painting makes me very happy.