The Creative Power of Darkness

An interview with Danish artist Kirstine Roepstorff

07/05/2017

The recent works of internationally-acclaimed Danish artist Kirstine Roepstorff (1972), who is representing Denmark at the 57th Venice Biennale, are neither loud nor immediately comprehensible and intelligible. They are contemplative and quite subtle. There even appears to be something spiritual about them which requires extra awareness from the viewer before they open up fully, and thus, makes them different from her earlier works. Roepstorff is best known for her work in collage, which has been her main medium for many years, going back to the beginning of her career; but she also works in sculpture, and recently – painting. Her large collages, created through appropriation of cut-outs from newspapers and magazines, along with a wide range of other materials like fabrics, wood, paper, photocopies, foils and brass, as well as beads, sequins and yarn (materials usually associated with women’s hobbies and domestic work), deal critically with existing power structures and political systems and our cultural subconscious. Roepstorff has been very versatile in her practice and in the use of materials, and has moved through several creative periods. In the 1990s, together with other artists of her generation with whom she studied at the Art Academy, she was among the initiators of the artist-activist group Kørners Kontor (Kørners Office), along with artists John Kørner, Kaspar Bonnén and Tal R, as well as a founding member of the new-wave feminist group Kvinder på Værtshus (Women down at the Pub). Both groups were founded as a reaction against established art institutions and male dominance in the art world.

Kirstine Roepstorff. Photo: Anne Mie Dreves

Today, the work of Kirstine Roepstorff seems to have become darker and more introverted. Why this shift? Could it have something to do with her return to Denmark after 14 years in Berlin, where she had lived and worked since the beginning of 2000? She made the decision to move back with her family to her childhood home in the countryside outside Fredericia, on the eastern part of the Jutland peninsula. It is far away from the urban buzz of Berlin, the much-loved city of artists and other creatives, and even quite a distance from Copenhagen, which is where we met.

How did you decide to turn your back on urban life, and move so far away from everything? It must have been quite a contrast...

I was born in Copenhagen, but moved to Jutland with my parents as a part of the whole 1970s ideology, which was all about collectives, nature, forests and free kids. In consequence, I left the rural life as fast as I could. I moved to Copenhagen, and used much of my youth to travel to New York and Tokyo and so on; I loved the urban life in all of its aspects. I enjoyed it and learned a lot from it – about urban spaces, the social side of it; the art scene… But there are two sides to it. On the one hand, I come from this beautiful place with a lot of space and a lot of beaches and forests, and which has been encoded in me through my childhood; it has been part of me for all these years, and subsequently, it is also one of the reasons I so enjoyed crowds, the night life, diversity, and the cultural differences. But on the other hand, I had used up my share of curiosity and I had reached a point where I had had my fill. The inner need for space began to manifest itself. This process began about ten years ago, maybe even before I was aware of it. When I look back at those last four or five years in Berlin, I felt like a lion in a cage...I had urban claustrophobia. I had a need to feel the soil and the grass under my feet in some way; to feel the connection to the ground. Everything happened very naturally – my grandmother died, and my father, my two brothers and I had to figure out what was going to happen with the place where I had grown up: should we sell it, or maybe there was one of us who wanted to stay there. We found out that, in our own ways, we all wanted to keep it. But for me, it was still a very abstract and distant thought, one which I thought would take much longer for me to realize, but at some point, things happened very quickly… That opened a sort of window for me, and it happened how it usually does with windows to possibly-new chapters in life: they open and close, and you can choose to step inside, or you can choose to pass by.

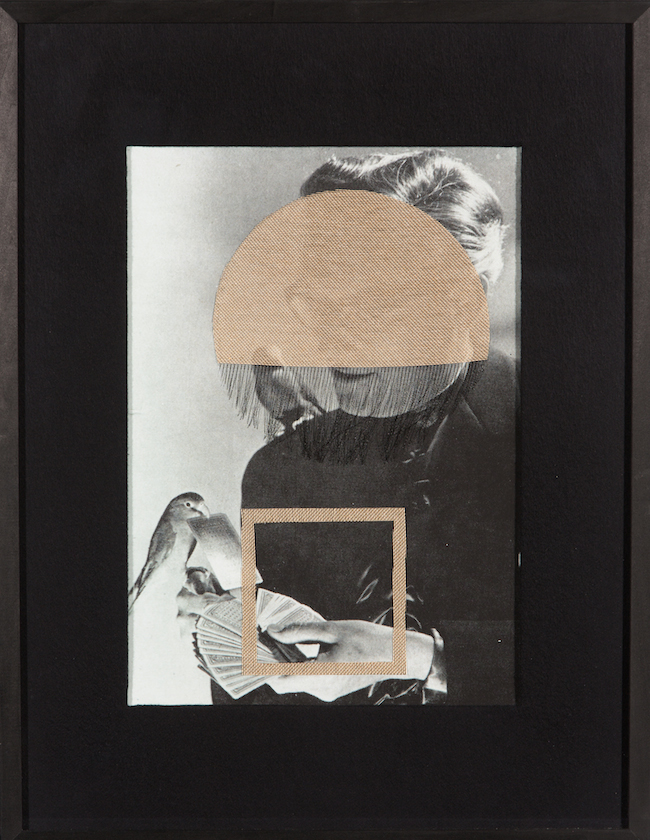

Parliament (Stop Woman), 2005. Mixed media collage. Courtesy of the artist

East, 2009. Mixed media collage: textile, paper, and foil. Courtesy of the artist

Did this influence your artistic practice as well?

Yes, of course. My last years in Berlin were affected by the fact that I was probably a bit tired of the art scene, and also by having three children in three years – which also makes you distance yourself comfortably away from a vibrant, extroverted life. Suddenly, I was in Berlin with three small children...which is a fantastic city to be in with kids, but our flat had become too small. Everything is in a state of flow… Then we ended up in Jutland, and we had to renovate this old, huge house and build an atelier. Suddenly, we had swapped a pulsating urban life for a full-on country life; it was a huge change.

You used to work with collages – which were explosions of images, whereas your recent works seem more introverted, contemplative, and darker. Does this have something to do with the change in your surroundings?

It is difficult to say what came first – the chicken or the egg. I can also see this change, but I think it started in Berlin; however, it has had a chance to materialize only now, in the new surroundings. 20 years ago, the point of departure for my collages was a frustration with the world – I was young and angry (definitely with good reason), and I used this frustration, anger and confusion about the world in my collages in order to understand or deal with the amount of information you get when you look at the world. It’s one thing how you see the world through your own eyes, and another how you see it through newspapers, magazines and news streams, and then measure this up to your own view with a common opinion. Therefore, collage was a useful tool with which to dissect reality and put it together in new ways – it was my tool to cope with all of that.

Presence Of Absence, 2012. Hand-dyed fabric on wooden board, Photocopy. Courtesy of the artist

But the amount of information out there hasn’t become less; in fact, it has exploded today…

Yes, but I have become older, and one of the advantages of becoming older – and there are many advantages to becoming older – is that it becomes easier to prioritize what to focus on. I think that in some way, the massive amount of information today also makes it easier to prioritize because there’s no way in hell that you can navigate through all that without prioritizing. Therefore, it can go both ways: either you get completely disorientated, or, you become more focused on your inner development. I have put behind me the wrath of my youth. I can still become indignant and outraged, and think that things are wrong, but my focus is somewhere else. And this certainly also has something to do with the change in my surroundings.

Illustration #32, 2016. Pigment and cloth on fabric. Courtesy of the artist

Illustration #31, 2016. Pigment and cloth on fabric. Courtesy of the artist

So, you don’t miss life in the city?

I miss Berlin as a city, but not the city life as such. I love life in the countryside, and feel that I am exactly where I am supposed to be. I can become thrilled over something at least five times a day, and have these small moments of happiness about something that I had no idea could make me so happy – some small occurrences on your way, small observations in nature, a falling leaf, a particular light setting through the trees, a worm working itself downwards...all that is a part of this natural, seemingly insignificant flow...it is filled with spirit and beauty. What struck me most when I looked back on my life in the urban environment was the feeling that I flew through my life; and now, I feel that I have arrived in my life. “Being” has, in a way, become more present, while “existence” has receded into the background, and it’s fantastic.

Everything in the world is currently subject to change, and no one knows the exact outcome of it all, but you seem to have found peace within yourself. Don’t you feel affected by all that’s happening at the moment, and feel the need to respond as an artist?

You bet I do! I am only human, so of course it affects me. It concerns me, but I am also excited and curious, even though I sometimes ask myself – where is the world going? What are we doing? Who is defining our values? Where are our common visions? And where are our dreams? We live in a society that has forgotten to dream, to think outside of what we normally think is possible. Therefore, my inner peace lies in the faith that everything is subject to change – things change, period! How we initiate the change is in our own hands, whether it’s a positive or negative change. But my inner retreat, which has resulted in us now living in the middle of a field in Jutland, and not Kreuzberg in Berlin, has given me more courage, curiosity, engagement and love for the surrounding world, because there is now more space for that. It was not intentional in the beginning, but where I am now, everything changes without me taking part in it – in nature, everything grows very fast and changes continuously, therefore I can take a much more observational and reflective position than in an urban space, where you constantly have to make things happen. It is a huge privilege, but it allows you to reflect both on yourself and your surroundings.

The whole living system, which is the entire planet with humans, animals, nature, its stratosphere – the whole ecosystem – all of it is out of balance. A great deal of my project for the Venice Biennale is about this imbalance in our mutual reality, which creates situations like now – with a lot of change. Things have always changed, but at the moment, they are changing extremely fast – the migration, the shaky economy, the power structures as we have known them for decades are unstable, and the value system that we, at least in the Western world, have built our mindset on, is stumbling. Everything is like an old dinosaur which is close to falling apart at any moment, and that triggers anxiety in most people because we no longer know where we are heading – we don’t know what the future will be, but it is obvious that the structures upon which we have built our identity as a society have become weary. In such situations, most people try to hold on and fill themselves with fear, but they forget to see the possibilities that emerge because when things collapse, a space for something new emerges.

Time Unknown, 2013. Collage, photocopy, textile, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist

Do you believe in the creative potential of change?

It’s not something I believe in – it’s something that I know is true. Obviously, when something collapses, something new materializes; the question is just – what is it? For my Venice Biennale project, all this formless “new”, with which we are still unfamiliar with, I have chosen to call “the darkness” – the darkness that has no shape.

The title of your project for the Danish pavilion is Influenza: The Theatre of Glowing Darkness. Could you please explain the concept behind this?

My point of departure for the project is the idea of the state in between its collapse and before the “new” has found its shape – it’s the very moment of creation. Everything in our world comes into existence from the darkness; everything begins with the darkness – it’s the most potent and fertile space.

Just like the Universe?

Yes, exactly! Therefore, with my project, I insist that we have to reconsider the darkness in order to change our view of the darkness. We are in the middle of dark times, where things don’t yet have their true form, where everything is in the process of disintegration. Therefore, we have to let go and open our eyes to see what is the “new” that might emerge; something new that we can believe in, and build our society and values upon, and in which we can create new structures. We have to see the potential instead of trying to hold on, because that prevents us from seeing the possibilities. Basically, it is a tribute to the darkness, and a discussion about the potential of the darkness. It is difficult for us to understand that a culture also needs regeneration. In our society of propulsion, we can’t understand that continuous progress can be a threat for the whole of society – we seem to think that it is unacceptable to take a break. Over the decades and centuries, we have built a culture of progress that accelerates without the awareness that everything progresses to a point where decline begins in order to be able to move forward again. It is the rhythm of life, and we are part of it. If we are unaware of this natural process, the change becomes very dramatic and causes enormous pain, suffering and fear. Regress is natural, but we have to figure out how to use it. Darkness is a positive thing and full of potential; it’s our new resource.

In our Western culture, we have this unhealthy cultivation of light. In other parts of the world, there is a different relationship with the darkness, with formlessness, with death, but as the world has become globalized, this has become a global condition.

The Angler, 2014. Brass, Kevlar line. Courtesy of the artist

The spiritual seems to have an important role in your work. What does spirituality mean to you?

We are all spiritual beings, but there is this paradox in human existence that we have these inner needs – intuition, an inner voice, empathy and love – and we are linked to nature more then we are willing to accept; but then we have our physical bodies that are full of resistance – the body makes our soul heavy and slow with all of its everyday needs. The essence of our existence in a body is resistance, which is a part of our challenge and suffering as humans. On the other hand, the body is also a vehicle for our experiences; in fact, the body is the intelligent part of our physicality. For many years we have favored the smartness of the brain, but our mind has to understand and respect our body; ultimately, it always has the last say. In our culture, we have given too much authority to the head. The interplay between the mind and the body is extremely important, therefore, at the moment, I am very much enjoying working in sculpture because sculpture has a direct connection to the body. Sculpture is also hard to work in, and it has a very direct way of communicating with the body. It thrills me and challenges me.

How do you choose the materials that you work with? You used to work a lot with brass, which is a fragile material compared to the concrete that you currently work with in your sculptures.

With my brass sculptures, I tried to portray sound: to make sound visible based on the idea that everything is a vibration, as, for example, a color is not just a color – it is a form of vibration. I was curious about how one could visualize a sound. I began making some collages to which I added what I regarded as elements of sound, which was basically, whatever I had in my hand – for instance, cardboard. However, nobody understood what I meant with that. Then I made the same elements out of brass because brass produces sound, and many musical instruments are made of brass – that worked better. Then I began working with these, as I call them, sound sculptures, which were brass mobiles. They had this human form and represented these vibrating beings which are images of us, humans. These sculptures resulted in a sort of poetry.

Why did you begin to work with such a heavy material as concrete?

I have always loved concrete; I had earlier made some concrete and glass sculptures. I love materials that have this inherited purity, like glass and concrete, both of which are materials related to sand. Brass contains tin, zinc and copper, and there is an element of alchemy in it, which I like.

Rehearsing Density #2, 2016. Concrete and brass. Courtesy of the artist and Andersen’s Contemporary

The focus of 57th edition of the Venice Biennale, with the title VIVA ARTE VIVA, is art and the artist – about the role of the artist and the creative power of art. How do you see the role of art today?

I have worked in art for 25 years, and I have always loved it, but I have never understood how you actually could make use of art; for me, it is like football – it is more fun to be part of it than to just watch it. However, during the last two to four years, I have realized how important art is, and how extremely important it is for society that there is a field that is unproductive and free, but which is visionary and creates certain values. I am not only talking about visual art here. Whether it is poetry, music, storytelling or dance, you name it – all of the free-floaters who have given up the conventional security of life because they insist on following their inner voice, even if it leaves them out of the productive market-oriented society – because this is a very special space in which visions are more likely to be created. Therefore, it is so sad that they cut down on creative educations and educational institutions because we need them now more than ever.

So, you mean that art can create change?

Art, as such, does not generate direct change, but it can create consensus and awareness, and feed the world with visions and dreams which we thought were impossible.

How did your work with the Biennale come to be? There is no curator for the project…

I appointed a consortium which functioned like a workshop. We met four times over the last year, during which time we had workshops and discussions about darkness. The members of the team were all curators, but were told not to curate; so, I have used them as both material and as interlocutors. It has been a collective project. There is not just one artist with one voice; multiple statements have become a part of the pavilion.