Love and Drugs Have No Borders

An interview with Israeli artist Sagit Mezamer

03/10/2017

The largest-ever Israeli contemporary art exhibition in the Baltics, Dreams and Dramas, encompasses many subjects and themes – the mythical and the mundane, current conflict and past traumas, lofty ideals vs. the harsh reality of today’s Israel, and, as it pertains to the following interview, drugs and drug addiction.

More specifically, the subject is opium and how, over the centuries, the substance has experienced agricultural booms and bans, undergone import and export, and even replacement and artificial synthesis. It has elicited wars and mass euphorias, and in various times of history has been called the Devil’s Gift, the Sacred Anchor of Life, the Milk of Paradise, and the Hand of God. Arguably the very first authentic antidepressant, in The Odyssey Homer described opium as an effective medicine for forgetting, and now, the Jerusalem-based artist and curator Sagit Mezamer has made an in-depth study of the drug.

In her latest work, Mezamer follows the historiographic roots of opium and opiates in the territories of Israel and Palestine, as well as in the Middle East as a whole. The collected information is then expressed in multi-layered ways – knotting and untangling myths and stories, weaving together the historical and the personal, and melding the factual with the fictional.

It is the Riga public who will experience the premier of a part of Mezamer’s substantial study, a work that continues to be developed and for which a final, end result has yet to be clearly formulated or envisioned by the artist. What we will see in Riga is three works from a series of twenty drawings thematically based on Ancient Greek opium ceremonies; indirectly, they also speak about human relationships – dependence, co-dependence, and love.

The following interview is the first time that Mezamer has publicly spoken about this work.

Sagit Mezamer. Photo: Gustavo Sagorsky

In addition to your master’s degree in the arts from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, you also have a master’s in clinical psychology. Could you explain how you combine your knowledge of psychology with your creative work?

Life fluctuates; it consists of numerous coincidences. I never planned on becoming an artist, curator or psychologist. I’ve always had an interest in parapsychology and physical phenomena, which is why I chose the psychology program at Tel Aviv University. However, I must admit that I’ve never been keen on systematical, academic research. For that reason I can say that, as an artist, I’m very privileged that I can do research on things that life throws at me – various coincidences, people I’ve met, and stories I’ve heard. And unlike the science of psychology, with art, I don’t have to substantiate, justify, or prove anything. I can freely work on something for as long as it makes me happy and intrigues me. I find myself in a sort of web in which various parcels of information link together into one whole, and right now that is the web of opium and drugs. Every event somehow finds its own spot in the puzzle, and everything assembles into a unified material.

As an instrument, psychology helps me in dealing with people, such as when holding interviews or examining mental processes, especially in the context of love, as well as in cases of dependence and co-dependence.

Why the theme of drug use and addiction, specifically? How did you come about selecting the topic of opium and opiate routes in the territories of Israel and Palestine, and in the Middle East as a whole?

An important year for my interest in drugs is 1982. That is the year when Israel invaded Lebanon in an effort to secure peace at its northern border. The First Lebanon War started, which at first was called Operation Peace for Galilee. This military operation was supposed to last for just a couple of weeks, but it dragged on for almost 20 years. In 1982, my brother was deployed as a soldier to the conflict zone. When he came back, he described it as a paradise of opium, hashish, weed, and heroin. A paradise of forgetting.

When these soldiers returned to Israel after their service, they became the country’s first substantial wave of drug addicts. Narcotics were their tool for self-medication and self-care. A tool with which to fight against depression and post-traumatic stress from the war.

I got to thinking that perhaps these people could open up an interesting perspective from which to look at the history of a specific place or region. I became interested in the factors that spurred them to turning to seriously addictive narcotics. The story of drugs in Palestine and Israel aroused my curiosity.

Mother of Opium, 2017. Ink and water colors on paper, 120 x 90. Photo: Amit Mann

What are the most surprising things that you discovered in this story?

First of all, the fact that the first written mention of a place where opium poppies were grown was Phoenicia – the greater part of what is today Lebanon and northern Israel. With time, poppy growing spread to Crete, which is where the oldest records of opium ceremonies are sourced (The work Mother of Opium, which will be on view in the Riga exhibition, is closely linked to this ceremony in Crete as alluded to by the terracotta figurine of a woman wearing a crown with three opium poppy seedheads, dated 1300 BCE.) Similar ceremonies took place in Egypt around that same time. Later on, Alexander the Great introduced the people of Persia and India to opium. Millennia after that, the British, through their colonies in India, used the widely available opium in their trade with China; as a result, a third of China’s population became addicts. This eventually led to the two Opium Wars between Great Britain and China, and the rise of opium addiction in Europe. Chinese immigrants to the USA took opium with them, and opium farming in Pakistan and Lebanon began anew. After the events of 1982, opium, now in the guise of heroin, flowed into Israel. Judging by history, it is evident that the opium trade has always thrived in zones of war and conflict.

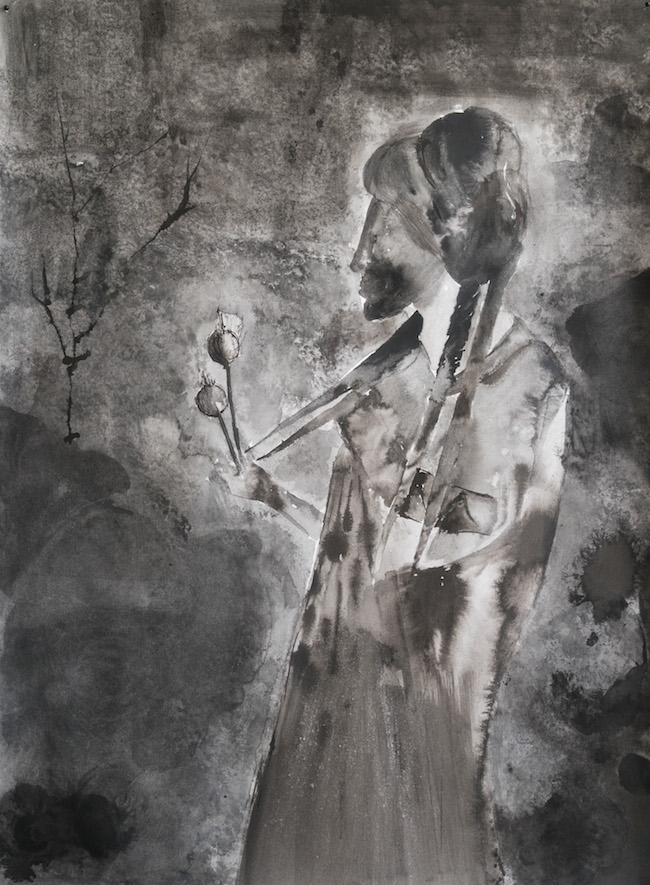

Nothing But Longing I, 2017. Ink on paper, 85 x 65. Photo: Amit Mann

Could you go into more detail about the research process and the methods you used?

I read books and went through archive materials. I went to a conference with the inspiring Canadian therapist Dr. Gabor Maté, who specializes in neurology, psychiatry, psychology, and the study and treatment of addiction. I also collected materials from places I visited. For example, when I was doing a residency in Switzerland, I found out about this abandoned building that used to be a hotel for orthodox Jews. This dilapidated structure had become a shelter for the local drug addicts. A stench filled the air, and traces of drug paraphernalia littered the place. The photographs that I took of this place became another foundation for my research and a part of my archive.

Another important field of research for me is personal conversations – talking with addicts and dealers, as well as with therapists. Specifically, my intention to work with anonymous interviews done with dealers revealed the precise routes with which drugs enter and leave both Israel and Palestine.

Nothing But Longing II, 2017. Ink on paper, 85 x 65. Photo: Amit Mann

I can imagine that you encountered some unexpected turns of events during your research…

In 2014, at the contemporary art and culture center Yaffo 23, I met the artist Bill Drummond, who invited me to curate the residency program at the historic Curfew Tower in Cushendall, Northern Ireland. When I arrived there, I became interested in the tower’s history. It turned out that the tower had been built in the 19th century by the eccentric Francis Turnley, a co-owner of the East India Company – of course, I was already well aware that the East India Company had been the most important player in the opium trade!

I curated the residency program for two years, which were then followed by a series of exhibitions, events and publications, both in Northern Ireland and Israel. The title of the project is Nothing But Longing (NBL). Longings that have caused so many borders to be crossed. Drugs and love have no borders.

Is that when you began to think about geographically mapping the opium routes?

It happened three years ago, as I was sitting in a very popular chain café in Israel called Aroma. While waiting for my coffee, I noticed on one of their advertising screens a map showing all of the Aroma chain locations. On the west bank, in Palestine, there were none. Basically, it was a map that overlapped with the Green Line, which after the 1967 war designated the Occupied Territories. Aroma hadn’t realized that they had, in fact, made a political map. I began to wonder what it would look like if I drew in the drug routes on this same map… There would be no national borders. People suffering from drug addiction are everywhere. Nationality has less meaning. There are only socio-economic and personal reasons for why they have pain, and then this addiction takes hold of them.

Israel and Palestine are both in conflict zones, and people on both sides have experienced things that they would rather forget. This map of drugs in Israel and Palestine would have no borders – drugs are everywhere. The only differences would be the forms of the drugs – more well-to-do areas would have one kind of drugs, while poorer areas have others kinds. In Gaza, for instance, there is more abuse of prescription drugs, the kind that treat neuroses. It is precisely these political and socio-economic aspects that I want to point out.

How do you transfer your research to art? Which parts of your work will we be able to see in the Dreams and Dramas exhibition in Riga?

I draw. My mind, my vision, and my hands come together in the drawings. The drawing is my thinking tool, my means of research, and my method. To me, the drawing reveals much more than my mind can. When I began to work on Mother of Opium, it revealed new and undiscovered horizons, and it freely led me to every subsequent drawing. They followed one another as in a free-flowing stream of consciousness.

I suffer from a kind of color blindness which is very rare among women – a red-green color blindness. That’s why I’ve always been drawn to the black and white; ink and watercolor drawings intrigue me.

Nothing But Longing, 2017

Do you know of other artists who have chosen drugs as their subject matter?

Over the past few years, drugs and drug addiction have become increasingly talked about in art and culture. There are artists who have chosen marijuana and hashish as their subjects. There have been artists who have studied psychedelic drugs. I think the work of Danish artist Joachim Koester is excellent. [Koester has studied the historical portrayal of drug experiences in culture – A.Č.]

May I ask – have you tried opium yourself?

I’ve tried a few things in my life. I’ve never been addicted and I’ve never used drugs to compensate for something lacking in my life. I tried opium once a couple of years ago.

What is your opinion on using art as a therapeutic tool for solving psychological problems, i.e., art as a medicinal method?

My instinctive answer would be that anything that is being done honorably and with true interest and enthusiasm has the ability to heal and make someone a better person. If artists can help others with their work, that’s great. I’ve never been interested in art therapy. My view is that therapy is therapy, and art is art.

The exhibition Dreams and Dramas will be open to the public in the forthcoming ZUZEUM Art Center from October 7 to November 5.