A dialogue with the Dead Sea

An interview with Israeli artist Sigalit Landau

02/11/2017

Sigalit Landau is one of 14 Israeli artists whose work is currently on show at Dreams and Dramas, an exhibition of Israeli contemporary art organised by Arterritory.com at the up-coming Zuzeum art centre in Riga. For more than 15 years, Landau has been experimenting and creating art at 456 metres below sea level, at the world’s lowest, and also saltiest, point on dry land – the Dead Sea. The area around the sea, which is 50 kilometres long and 15 kilometres wide, looks like a lunar landscape. With salinity at 34%, the Dead Sea is almost ten times as salty as the oceans, and it’s impossible to sink in it. There are no ships on the sea, and there is no life in its oily dark, mineral-rich waters. The Dead Sea borders three different administrative territories – Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan – and, unlike the seeming numbness of the water, its shores pulsate with human-created tension. Tourism is popular, and the ‘gold vein’ of minerals has given rise to several industries, which are gradually leading the sea to destruction. Of course, there is also no lack of political passions.

Landau calls the Dead Sea a mirror that assists her in addressing (through the language of art) her relationship with herself and with her nation’s past. Her artwork is a story about what this immense body of water – called the Salt Sea in the Old Testament, the Sea of Sodom in the New Testament and the Devil’s Sea during the time of the Crusaders – means to her and the people living around it. How has it influenced their fate in the past and still today? Over the past 15 years, the image of the Dead Sea has materialised in Landau’s work in performances, video art, and also crystalline objects, or salt sculptures. A book titled Salt Years, documenting the relationship between Landau and the Dead Sea, is currently being prepared.

Landau was born and grew up in Jerusalem, and the Dead Sea is literally the sea of her childhood. She and her family spent many Saturdays on the sea’s shores. Her mother was born in London after her family’s escape from Vienna. Her father was born in Romania, survived the Holocaust and immigrated to Israel when he was 10.

Until the age of 17, Landau was a passionate dancer, but she was forced to give up this dream due to health problems. She has always been known as a bit of an outsider – extreme hairdos, dressing in workman’s clothes while studying at the prestigious Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, and spending most of her time in her studio. Today she is one of the internationally most recognised Israeli artists. Her work has represented Israel at the Venice Biennale and has been shown at many distinguished art institutions around the world, including the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin,The Brooklyn Museum and Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Landau stands out in the art world with her independence. In recent years she has scrupulously removed herself from the general art market system.

One of Landau’s first internationally recognised works was her 1.48-minute-long video Barbed Hula (2000). In it, she swings a hoop of barbed wire around her waist while standing nude on a Tel Aviv beach. The camera does not show her face which faces the sky, only her body, the beach and the water. The video was filmed at sunrise and tells about women and politics, about the feeling of danger that has always been present in the lives of the people living here and the marks it leaves on bodies. The hoop of barbed wire turns faster and faster, the pain disappears because the barbs face outward, they do not damage the skin and at the same time embody an existential duality in which pain, vulnerability and security exist next to each other.

Sigalit Landau. DeadSee, 2005. Video, 11:39 min. loop. Courtesy of the artist

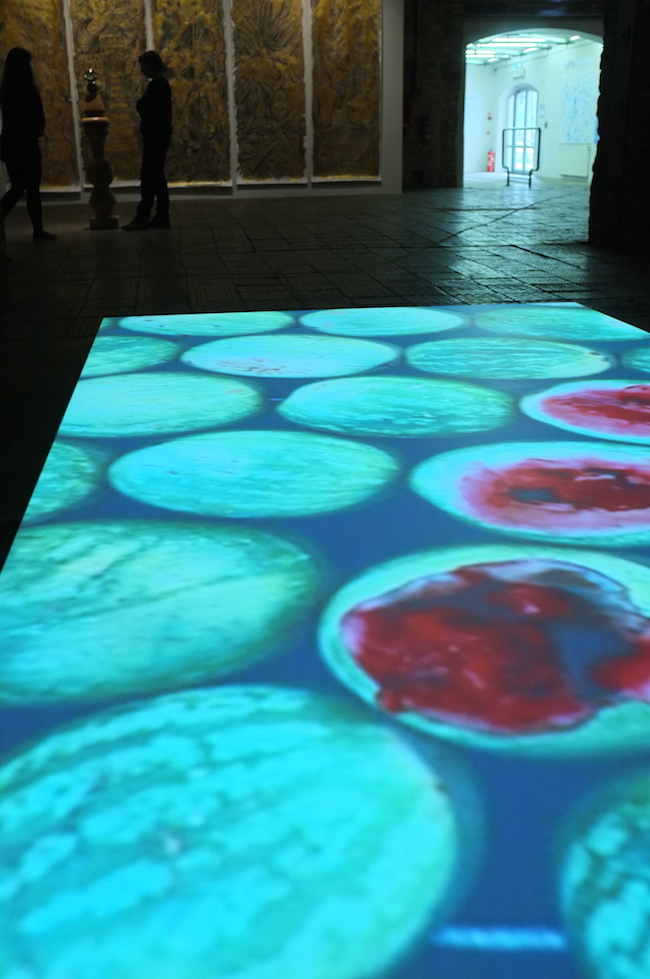

Landau’s first Dead Sea project was DeadSee (2005), a video that can also be seen in Riga. In it, the artist’s nude body is symbolically locked into a slowly unravelling spiral of 500 watermelons floating in the Dead Sea. The serene display lasts 11 minutes and resembles a still-life image that has come alive, like an onion slowly, slowly being peeled back, each layer full of submerged feelings, signs and symbols. At first, the sweet raft of luscious colour with which Landau’s body slides through the water seems hypnotically beautiful, even though some of the watermelons are ‘injured’ and their red flesh is subjected to the sting of the salt water, just like Landau herself. In the end, the spiral becomes a long, freely floating line of fruit that escapes the frame.

Sigalit Landau. Gdansk#1, 2011. Color print, 66 cm X 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Landau’s 2011 video Salted Lake focuses on two shoes crystallised by the Dead Sea. In the middle of winter, Landau transported the shoes to Gdansk, a city linked with one of the most tragic episodes in the history of the Jewish people. Placed on the surface of a frozen lake, the shoes slowly melt a hole in the ice until, by night, they sink into the fresh water, together with the pain and memories. This work was exhibited in Israel’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

But the work that has most resonated with audiences is Landau’s Salt Bride (2014), which is also her largest work to date within the Dead Sea series. Last year it was shown at the Marlborough Contemporary gallery in London and immediately became a media sensation, including on social media. Salt Bride is also Landau’s most poetic work of art, almost bordering on alchemy. In it, she submerged an ascetic, black dress from the early 20th century in the waters of the Dead Sea for three months. Together with her partner, Yotam From, she documented the crystallisation process in a series of eight photographs. The way in which the dress gradually grows layer after layer of salt is something quite metaphysical. At first, the layer is thin and resembles frost. But after three months the dress is no longer recognisable, having turned into a bright, white garment of a bride. The crystals are saltier than tears, but at the same time they look as innocent and chaste as freshly fallen snow.

Sigalit Landau in collaboration with Yotam From. Salt-Crystal Bridal Gown VI, 2014. Color print, 163 cm X 109 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Salt Bride was inspired by an old Hebrew story about a young woman named Leah. On her wedding day, when she is to marry a man chosen by her father, the spirit of her dead beloved possesses her body. The story was immortalised in the early 20th century in a play called The Dybbuk by S. Ansky, with the main role famously played by the legendary Jewish actress Hannah Rovina. Leah become a defining role for Rovina, and the dress used in Salt Bride is a precise copy of the dress she wore on stage. In Landau’s interpretation, however, the black dress symbolising Dybbuk’s spirit is reborn as a wedding dress.

Currently, Landau is working on the project of a salt bridge, an idea she originally wished to realise already in October 2014 to mark the 20th anniversary of the peace treaty between Israel and Jordan. It has not yet happened for various political and bureaucratic reasons. But Landau believes that her utopian vision will one day become reality. Now, as an alternative plan, the bridge made of salt crystals is intended as a floating island symbolically searching for the shore as it drifts in the waters between Israel and Jordan.

Our conversation took place on Skype shortly before the opening of the Dreams and Dramas exhibition in Riga. The temperature in Tel Aviv was 29°C, while in Riga it was 13°C. But Landau and I concluded that we were at least united by a single time zone.

How has your relationship with the Dead Sea changed over these past 15 years? I assume that in the beginning the dialogue between the two of you was much different.

To be honest, both the sea and have changed together – as I’ve experimented and as my ideas have developed – changed developed a dialogue and ritual. When I began this project, I had a different view of the Dead Sea. I chose the site mainly for its unique character. Everything in its water swims and is buoyant, everything is physically different there – people’s relationship to the mass of their bodies and the way in which they experience their bodies, the water, the acoustics, more oxygen in the atmosphere.

The watermelons you see in the video are ‘inspired’ by the ones that grow in the desert by the sea and are the first crop of the season. Growers in the Arava Desert have been experimenting with using salt water from local saline underground wells for quite some time now, with success. It turns out that there are several plants that not only tolerate but actually thrive when watered with groundwater containing a considerable amount of salt. True, it’s not water straight from the Dead Sea; it’s less salty and comes from deep underground. But when I read about this study and saw these watermelons and their colour – this oxymoronic striving for extra-sweetness in a life-less, saltwater environment – this seemed to me like a metaphor for homeostasis, for the way in which we have adapted to a specific harsh place. And that’s what I’ve been doing this whole time – trying to get used to this extreme place in which there are no signs of life but which has some very different qualities and hidden abilities. The ecological conditions, the political situation, the topography, all of it changes. But at the same time, these powerful myths remain, the myths that every child who grows up in this area knows. They’re just engraved in our emotional map.

I was born in Jerusalem and have always been more linked and intrigued with its eastern side. The people on the other side of the mountains, on the other side of the Jordan Valley. My world has also been influenced by the fact that my mother’s parents were passionate communists and then disillusioned socialists, and that my mum grew up in a Christian culture and tradition in London back in the 1950's. Her experience of immigration was tinted with a yearning of pilgrimage whilst celebrating the ‘kibbutz’ way of life, where we used to visit her extended family – two very bizarre and opposing approaches in my upbringing.

My mother died less than a year before I filmed DeadSee, and my presence in this distinctly corporeal chain of watermelons, my belonging to it, was like moving from something very extreme and metaphorical towards a sensual and intimate opening of wounds.. At first I wondered what I could do – in a way, I was in this weightless ephemeral staging, and I needed to understand what I am in the frame of this shot. Robert Smithson was in the back of my mind, but in front was the gaze of a camera looking down at the fluid canvas with the chain of fruit and my vulnerable body.

With time, I noticed that the odd things we forgot on the shore during the production and shooting of the first videos started to crystallise and lose both function and colour – the salt whitens and eliminated everything, and it seals like a scab of crystals and encrusting surfaces. I have been suspending objects in the Dead Sea for many years since then. Each ready-made or fabricated object has the ability to seal and heal; each carries a small story… This interaction creates new knowladge, new experiments and different ideas over the years. The political issues were aroused only in 2010 when I raised my gaze to acknowledge that the sea was also a "political liquid" shared by a country in the background of this medium and canvas of storytelling – Who does the sea belong to? Whom do I need to ask for permission in order to work here? When I try to build a bridge, do I need to talk with the government or with one of the industrial corporations? Who is incharge of the territorial water? Do they collabourate?

Sigalit Landau. DeadSee, 2005. The Dreams and Dramas exhibition in Riga. Photo: Ģirts Muižnieks

It’s no surprise that the Dead Sea is currently on the cusp of an ecological catastrophe. Each year its water level drops by about a metre. That’s due to the fact that the course of the Jordan River, the sea’s main source of water, has gradually changed over the years, but also because of seismic activity in the area and the industrial ambitions of corporations. In addition, as the water level falls, fresh groundwater is being pushed up, which dissolves the layers of salt and creates very dangerous and very sudden large holes which they are called sinkholes from time to time, by now so many have perforated the shores, and this is why the area looks and functions like an active disaster zone. They first appeared in the 1970s, and in recent years their number has really increased– there are already about 4000 sinkholes on the western coast of the Dead Sea. Some of them are up to 25 metres deep, with diameters of 40 metres. You’re driving along a road you supposedly know very well, when suddenly it disappears. That’s the reality that you can’t run away from.

I began looking at the colour white with different eyes, by sinking a blue flag into the sea and later pulling out a white flag, by sinking a black dress into the water and transforming her to be what I could be. This is a way in which something is as though erased, how it is lost but witnessed, how it leaves or stays connected to the sea basin. But as a parallel, there’s also this very positive feeling – gifts and surprises created by nature. Like farmers who delight in a new harvest, we’ve had wonderful moments in our relationship with the Dead Sea, too. Even though the concern for its fate is always in the background, and more so year by year and day by day…

On the other side of the river is Hashemite kingdom of Jordan, and the border runs down the middle of the sea. There’s peace between Israel and Jordan, yet there are no ships on the sea, and the tourism between the two lands is very limited. In a way, this is a very salty and frozen border. In 2014, wishing to celebrate 20 years of peace between the two countries, I planned to sail across the sea in a boat, to mark the route of a future floating hbridge. I looked for ways in which to do this gesture legally, a journey that combined art and activism. Needless to say, I came up against an enormous bureaucracy. It is true that, in order to avoid calling something a catastrophe, you can always say that you expected something different, but you end up having to work within the situation that reality has set in front of you. And then you understand those utopian people who are able to defend their ideas with action. So, not having obtained official permission, I nevertheless rowed to the middle of the sea in a boat that was full of fantastic people from all over the world, from Jordan, too. It was documented on video, sort of. Well, in this case the middle of the sea was quite approximate – considering that the Dead Sea borders three different countries, it was impossible to determine the exact border.

Before the water – there is something very healing about the air at the Dead Sea. There’s a lot of oxygen, and you really have the feeling that this place can and wants to cure you also spiritually. It simply lets you be and gives you the peace to think about life. Kind of like being in the desert but with an allusive sea and a majestic, mythological narrative – there’s always this surreal feeling of pureness here, because there’s less nature and more minerals.

And those are also the questions we’ve been been asking in the book we are now creating, which documents my 15-year-long relationship with the Dead Sea. Why did I come here? What brought me here? What does it mean to be a Salt Bride? What does time do to us? How does the political transform into the historical, and how can we help make things better? This work is very closely linked with traditions, but also with the idea of devilment. It’s a story about the sometimes so elusive interspace – the space between life and death, the space between man and woman, that volatile moment of ‘here and now’. Loss and sorrow, the bereavement process that can take place through art. How we replace something we are missing. People we miss, a culture we miss – also in a philosophical sense. The salty wings of ‘lack’…

When I’m working on big projects, I always feel like there’s some kind of communal sensitivity, a shared heart/brain. Of course, I make my own decisions, but at the same time I also take the time to tune in to and listen, and it’s important for me to feel and be in a passionate surrounding regarding the things we’re doing. I could not do it alone. It’s very easy to dedicate wonderful words to the Dead Sea, but it’s very difficult to work here in the summer. Yes, it’s romantic, but it’s also very harsh.

An essential part of my work is the fact that I’m an independent artist. At least at this point in my career, I do not rely on any norm or system. I’m trying to survive without all of that for a bit – without galleries that I’ve worked with before, without exhausting, hyped art fairs. I’m taking a break from that loop.

Sigalit Landau. King of the Shepherd and the Concealed Part, 2011 [detail]. Installation view, One Man's Floor is Another Man's Feelings, 2011, Venice Biennale, The Israeli Pavilion. Courtesy of the artist

Objectively, there is no life in the Dead Sea. But what do you think – is it really dead, or is it nevertheless a living organism in some very unique, special way?

Many have tried to live on the shores of the Dead Sea, and many still manage to survive on what they can take from this area. Palms and dates are grown here. Life has never been easy in this region, and it’s still not easy today.

Most of the area near the sea is polluted on both sides, although it looks like it’s more polluted on the Jordanian side … There are hotels and industries that sink metal pipes into the sea and pump out water in an effort to extract minerals. When there’s no more water in one area, they sink new pipes further north. The sea is full of metal. But there are also more and more people who are aware of this situation and are trying to find a solution. A lot of money is being made, and for tens of thousands of families this employment is their livelihood – it’s the same in Jordan. It needs to be revised and decided; the scope, the conditions, the share of the profit and the future of the sea… which I believe will in the end be mainly tourism, wellness, sports, peace, education and, of course, culture, but this may take a whole lot of time to understand. Until then, it just needs to be monitored transparently. We are dealing with a few huge corporations and also, quite rightly, a historical national ‘pride’. This sea is Israel’s only natural resource. In general our economy is based on human resources…and Israel is also tiny. People forget this.

This has always been a harsh place, a place associated with people who work very hard in order to survive in this environment. Love is necessary for something like that. In a way, this place is like a metaphor for the whole nation of Israel, only more muted. It’s like a mirror, and as soon as I notice some new reflection, I also catch sight of myself. Sometimes also a part of my body. That part which has died.

Sigalit Landau. Paradox, 2017. Child size Hassidic wedding dress, veil, shoes, tapestries, suspended in the water of the Dead Sea. Courtesy of the artist

Do you think that art can change things in the world? I mean also in the context of this Dead Sea project.

There are very many examples in art history in which art borders on activism or better: it has evoked drama and paved the way to a braver and louder voice. But that’s never been a point of departure for me. I don’t know if I’ve ever changed anyone’s mind, so I can’t really answer the question. People connect to my art in an intuitive, emotional way. But I have reason to believe that our studio’s activities concerning this place have been noticed. I think we’ve succeeded in revealing new things about this sea and about what it could potentially be like. It’s a journey that has still not reached its end, so I don’t know whether I’ll manage to change anything or not. I know that people have heard about the idea of a symbolic bridge – also in Jordan, where I’ve done lectures. But that’s all in a parallel world. The people who have real influence in this area don’t listen to artists. There aren’t any artists at their discussion tables. Over these past 15 years, there are few countries in the world where my films haven’t been shown, especially DeadSee. And the salt objects, too. The only thing I can do is tell my personal story – that’s my homage, my offering, my contribution.

When The New York Times and the Artsy website published articles about the salt dress, it was read by at least 20 million people. The articles didn’t always mention Yotam’s and my name, but Israel, Palestine, Jordan and the Dead Sea were mentioned. And as soon as people are interested, they always want to find out more. There are no simple solutions. We live in an extreme place, and we also subject our love for it to an ongoing test. Every year we have to endure this test again. In a way, anormality becomes our normality. But if we look at the world in general, it has everywhere become much less casual than it was before. Everything is much more extreme, and Israel is only one small part of the world, blown way out of proportion.

Your work has to do with borders – literal, structural, abstract. What does border mean to you as an artist, and are there some borders you know you will never cross?

I often looked at this word ‘border’. It is firstly just a word, and language in itself is one of the first and sometimes the worst kind of border and zone for me… On a more practical level: I once believed that artists from both sides of a conflict have more in common with each other and can create discussions that can pave new ways to lessen suffering… After trying hard to find a partner outside of my identity and culture, across the divides, I’m realising that looking inward and acknowledging the limits and sink holes of my body and biography may be a more productive borderline journey.

.jpg)

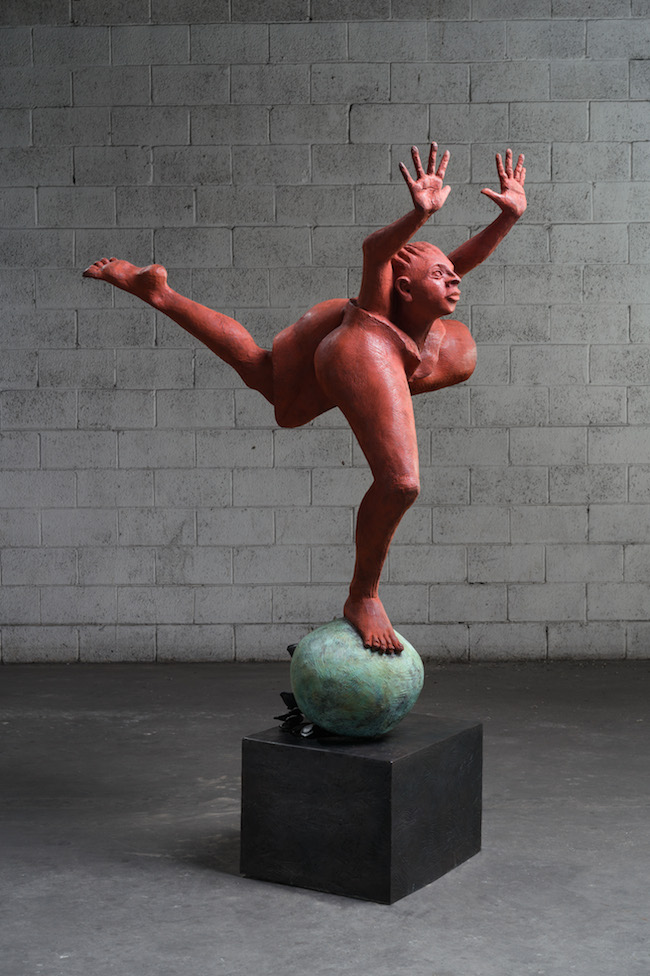

Sigalit Landau. I Lust, 2017. Bronze, 190x107(h)x109cm. Courtesy of the artist

The French sculptor Bernar Venet once told me in an interview that, to him, creating art is like an act of heroism. What does this process mean to you?

Yes, I think that creating good art is usually a struggle and a battle. It’s like going out to war, and I can identify with this feeling. We live in a war zone anyhow… Although I don’t know if it’s an act of heroism, because I’m usually not completely alone. And although it’s a process that involves some struggle, there are other moments when it’s like picking ripe fruit on a sunny day. On the one hand it’s a battle, on the other hand it’s harmony.

When the circle has been closed, the energy of our teamwork is transferred from the studio or location to the public. Opening closed ears and hearts and celebrating something that has nothing to do with consumer culture. Something that unites people, that crosses borders, genders and social status.

There are fewer and fewer constraints in contemporary art; there isn’t this strict definition that you’re either a painter or a sculptor. I work with various media and try not to confuse myself too much, though I am naturally a confused and distracted animal. I think an artist always realises that the moment when her work is finished, it can travel without her. It can become a part of a dialogue. Something that speaks to people and something they wish to enjoy. Some of these things still amaze me.

Sigalit Landau. Woman Giving Birth to Herself, 2017. Bronze, 117x216(h)x70cm. Courtesy of the artist

At the beginning of your career you very often used your own body in your artwork, such as the famous video Barbed Hula (2000). But unlike, say, Marina Abramović, you’ve never caused yourself pain. Why did you set this boundary to not harm yourself?

Seeing as other people tend to cause me pain, I don’t need to cause pain for myself (laughs). That’s not my role in this life. Like a ballerina – even if your back breaks, you cannot fall out of your role and you must finish the arabesque. You can only start crying after you’ve gone backstage. Because the audience is like your children, and the story has to be complete – you’re not going to tell your children that you’re exhausted, angry, nervous, and just leave me alone. I’m not criticising Marina, she does everything perfectly. But this control she takes over people’s reflexes sometimes seems manipulative to me. I think that people who know enough about victims know that they don’t want to scream like victims. Exactly the opposite – they want to hide it. And in my case, either ‘hide it’ or even better: encode it in a beautiful way, if possible.

In any case, Marina seemed to me much more powerful when she was washing bones and singing folk songs from her childhood during Balkan Baroque (1997) at the Venice Biennale, or even eating an onion, than when she was cutting herself in front of an audience. I wish to see essence in art.

Sigalit Landau. Day Done, 2007. Video, 17:15 min. loop. Courtesy of the artist

A few years ago you took part in the exhibition No Man’s Land: Women Artists from the Rubell Family Collection, which featured only art by women. Do you think there’s still a difference between women and men in art?

The art is the same language of art, but the experience of women and their perceptions and strategies can be unique to them. In most cases…in my case, body, life and subconscious are distinctly alien-feminine-collective with a strong attraction to all others. In techniques, I love crossing the lines back and forth, depending on the fluid conditions of the above – body, life, subconscious…things that happen to me.

The dynamics of women’s daily lives have not become any simpler. I don’t think it helps my career that I’m a woman. I would be collected and followed more loyally if I were a man. I smashed the glass ceiling and am left with the pieces of glass under my skin and inside me. In fact, it’s probably the opposite. Especially if I’m strong and have my own opinions – those are traits that traditionally belong to charming, charismatic men. That’s still the reality. But it’s possible that things have taken a turn for the better in that tiny part of western society that’s called the art world. The art world has filled with women in the last two to three decades: curators, critics, directors of small and medium museums. That’s simply the way it is – the art[ist] and the art world are not the same thing… And every day I realise that there are things I need to do just because I’m a woman, an older woman, a bit older than I used to be. And I am an artist-mother, which makes things more (a)cute. I could not imagine my life without gratefully and lovingly sharing it with Yotam and Imree, but I try sometimes – and that’s also important: trying to be Sigalit Landau.

Why did you decide to not work with art galleries anymore? As far as I know, you’ve changed galleries several times during your career. Does that mean you no longer trust the existing art market system?

It wasn’t like I just woke up one morning and decided to not work with art galleries anymore! With most of the galleries, our collaboration usually lasted about five or six years. A few of the ad hoc galleries I was just trying out – making an exhibition and then seeing if there was the right chemistry between us. I’ve also always been open to giving young galleries a go. But at one point this constant participation in art fairs started to feel repetitive. I have nothing against galleries if I see a real spark in the eyes of an adventurer/ess. They offer a great opportunity to artists. But if you start seeing that there’s no longer the real spark, then it’s time to change something. And as soon as you realise that you don’t expect anything, then it’s better to be on your own existential planet.

Sigalit Landau. Ectopic Pregnancy, 2005. Metal armature, papier-maché, and other mixed media, 101X75X103 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Your work Ectopic Pregnancy, which can be seen in the Dreams and Dramas exhibition, is made of papier-mâché. What draws you to this material?

Papier-mâché is not a high-art, professional material. But it’s very easy to work with and lets you do practically anything. Ectopic was made when my studio was near a gift-wrap factory. But what initially drew me to it was the fact that papier-mâché is so directly linked with reality, time and bad news – most of my sculptures have traces of text on them. I first worked with papier-mâché in 2002, when I made The Country installation. That was the time of the second Palestinian uprising (Al-Aqsa Intifada), and the newspapers and everything was full of news from hell. I took these headlines and used them to make images of fruit and people whose skin was covered/exposed with everything that could be read in the news at that time. The private and public.

Paper and glue – working with papier-mâché is very physical, very physiological, it’s like chewed paper, it’s dirty, it has a connotation of rumination. Advertisements and colours, it’s all mixed together, and in a sense it’s really like working with the loss of coherency. Kind of like making art out of shoe strings. It doesn’t cost anything. And a work of art that’s first been made in papier-mâché can later be cast in bronze. In that sense, I have no problem with it, no problem moving from this seeming nothing to much ‘finer’ materials. When I create art, I always have the feeling that I have nothing to lose. Even if it’s bronze or marble. I remember and celebrate freedom even in the realm of precious traditional techniques. I need freedom when interacting with the big inspiration in art history, when looking at daily life all around me, when reading and also when creating specific rules for myself and then later questioning them.

The Dreams and Dramas exhibition is a special project for Riga initiated and funded by the Riga-born businessman, collector, and patron of the arts, Leon Zilber.

The exhibition is ongoing at the ZUZEUM Art Centre through November 5.

Exhibition hours:

M: Closed

Tue – Th: 12:00-18:00

F – Sat: 12:00-20:00

Sun: 12:00-18:00

Guided tours:

Sat: 12:00, 15:00 / Sun: 12:00