A chance to touch another bubble

An interview with sculptor Ivars Drulle

07/12/2017

The Latvian public, of course, requires no special introduction to Ivars Drulle, yet not everyone may be aware that the last year has been especially productive for the sculptor. When he was nominated for the Purvītis Prize last winter, his work was noticed by a very prominent person in the Vienna art scene – the gallerist and patron of the arts Ursula Krinzinger. Thanks to her generosity, Drulle recently spent a month at an artist residency located in northern Croatia, where he bicycled along the mountains and developed new ideas for installations. The results of this process will be exhibited this winter, at one of Krinzinger’s galleries in Vienna as well as right here in Riga, at the Arsenāls exhibition hall. In order to complete the ambitious artworks planned for the shows, Drulle still has an immense amount of work to do; at the same time, he also has a whole department to head at the Riga Design and Art School. And so it was there, in the wooden building on Lāčplēša iela, among swarms of students and piles of sketches, that I met with Drulle to find out how things are going.

What are the tasks and concerns, in terms of art, that you’re focussing on right now?

It seems I’ve gotten myself into quite a pickle… Well, at the beginning of next year, in honour of Latvia’s centenary, five other artists and I are having a group show at Arsenāls, where I’ll be presenting a big interactive piece. I’m going to need someone to mind the piece every day – to work it and turn it on and off. It appears that the staff at Arsenāls won’t sign up for that, so I’ll have to pay a pensioner to do it. But that’s a minor thing. It’s going to be a month-long huge and fundamental exhibition with new works, based on the concept of ‘the country of the future’… Thanks to Ursula Krinzinger, I was recently in Croatia and I had planned on coming up with something for this show while there…

Who else is showing with you?

Krišs Salmanis, Aigars Bikše, Liene Mackus, Artūrs Virtmanis...are the ones I know of. Lately, my overall concept has gone in a direction that makes me think that it’s not interesting to present an artwork as a finished object – like a painting in the olden days, when you’d go to just look at it… It seems that all of our visual culture is, in large part, interactive...for example, interactive TV – no longer does one just switch it on and watch whatever is playing. You can skip commercials, fast forward, save it for a later time… A person can pretty much dictate what sort of pictures they’ll be looking at.

Should art go along with that?

Not necessarily, but it just seems to me that I could try that path...in which you don’t have a finished image, and the viewer chooses what they will see… Like on Facebook, where you can choose from which profiles or accounts the posts will show up on your timeline. In some sense, you’re controlling what you see, but not completely. It’s at least partly based on your choices. And that seemed interesting to me – to try and develop something in this manner. I myself often get tired of the same old works I see in shows. No matter how much I may like painting, sculptures and installations, I’m tired of it.

How far does this feeling of yours go? Would you go as far as saying that no one should paint anymore?

No, but I do believe that there are very few people who are able to say something new and interesting with painting. Maybe once or twice a year I come upon a painter or some paintings that are interesting to look at.

Could you name an example?

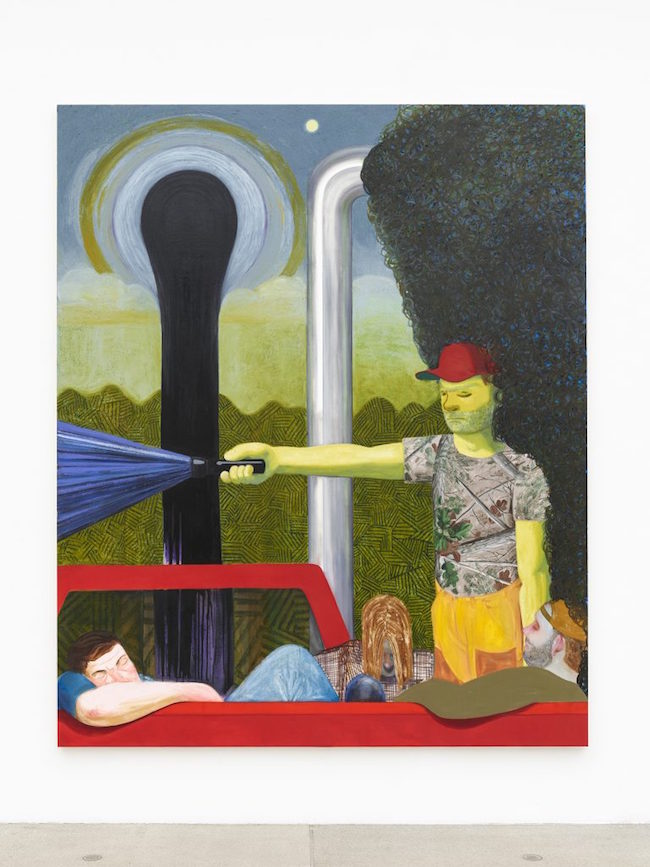

Yes. I was recently in Vienna to meet Mrs. Krinzinger, and there, in the Secession Building, was an exhibition featuring the American painter Nicole Eisenman. She paints these huge works, and she’s interesting in that she somehow pulls together history – historic scenes and historic styles – with today’s politics… Of course, it all has to do with Trump. She’s an American, and everything is going off the rails for them there. And you see [shows pictures], here is that river – green, disgusting, snotty – it’s falling into a bottomless pit...and that there is like a huge jaw – of a horse…? And these musicians are blindly playing music, and then all of that also seems to be falling into the pit… Of course, there’s the red baseball cap (everyone knows what that means), and he’s shining a light, but the light is black; black crude oil is flowing from the sun, and everyone over there has fallen asleep… Well, it seems to me that in works like these, painting is alive. There’s a serious feeling that she’s saying something new and different.

Nicole Eisenman. Dark Light. 2017

Nicole Eisenman. Going Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass. 2017

OK, so you don’t think of yourself as one of those who could still paint or sculpt, and that’s why you’re making something interactive.

Yes; my current feeling is that 99% of what I see makes me tired. I can’t say for sure that I’ll be different, but I try to think about what I can do. For the Arsenāls exhibition, I decided to call my project Laimes rats (Wheel of Fortune).

Like the ones on TV lotteries?

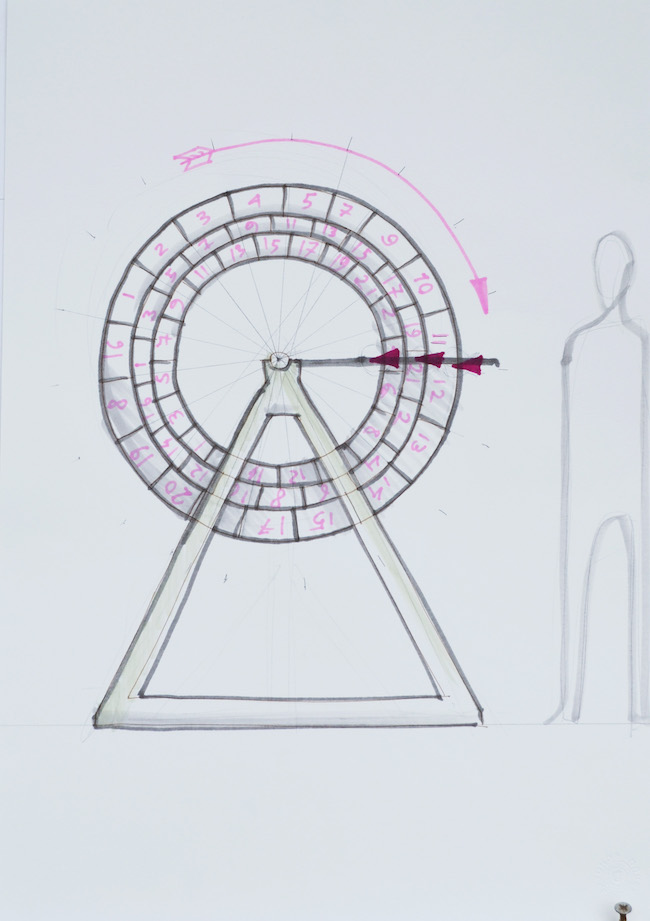

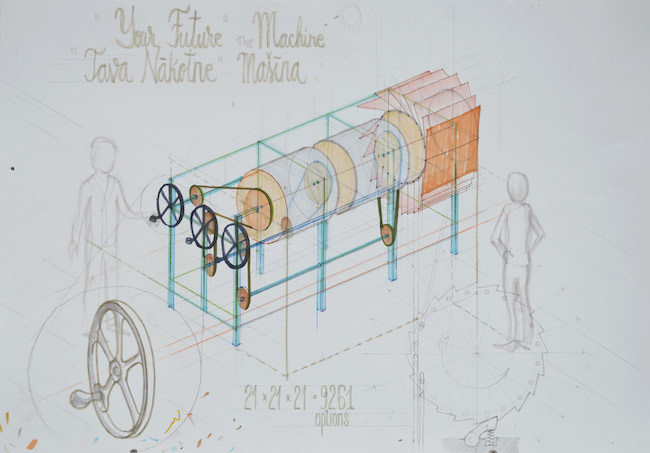

Yes, the ones that you spin and you land on a number – 20, 40 or 60… So for the theme of ‘the country of the future’, I thought – how can I be part of that, what do I know about that? None of us knows what the country of the future will be like, and that’s a good thing. Trying to guess at that is just as silly as looking at drawings from a hundred years ago where people imagined what the world would look like today. Today is much more uncertain and strange than anyone could have predicted. So then I thought, I can’t offer up a rendering of the future, but I can come up with variations, versions. The wheel of fortune idea will work like this – you spin it and a number falls out. I’ve drawn a schematic… See.

It’s about two metres tall.

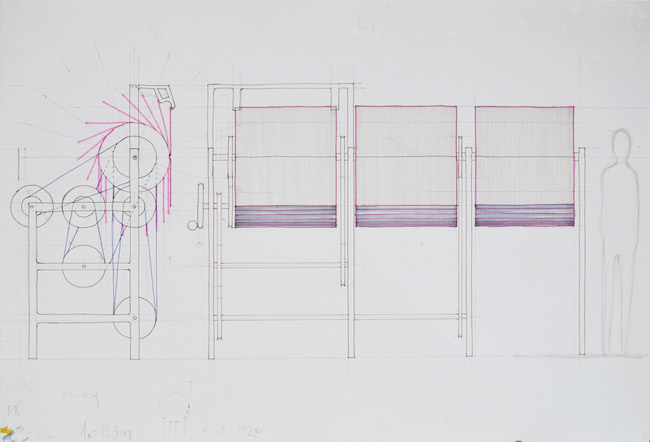

Yes, and there will be three wheels in total, so that you get three numbers, for instance, 11, 21, and 6. In any combination. And then there will be this kind of a mechanism, and every wheel will have 21 drawings. Which means that the total number of possible versions of the future will be 21 cubed, which is almost ten thousand… Each drawing will show something different – floods, rockets leaving the Earth, big mushrooms… So each person’s spin of the wheel of fortune will result in a three-drawing combination.

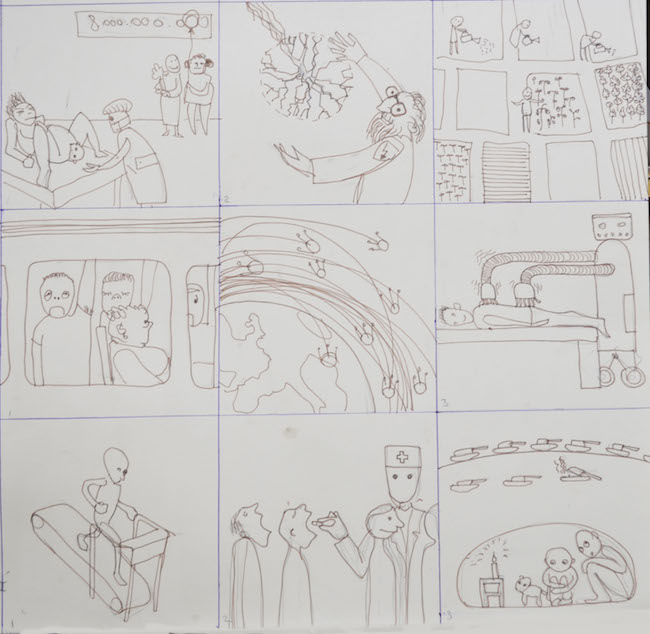

Sketches for the installation Wheel of Fortune

So you get three drawings that predict the future?

And then that is their future! That’s what it is. And I want each visitor to only have one turn at spinning the wheel. I don’t want someone standing there and spinning it again and again. That’s why I’ll need a monitor to work the mechanism. Everyone gets three drawings, that’s it.

Are you going to make those 63 drawings yourself?

Yes, yes. On 70x70 centimetre cardboard. They’ll be rather simple outlines. I came up with that during my residency in Croatia. After Croatia I returned to Vienna to meet with Krinzinger; she saw these drawings and some other works, and asked me to do a solo show at her gallery. That means I’ll have to make two of these wheels, since both the Vienna show and the Arsenāls exhibition are taking place this winter. It’s no joke; everything has to be made from scratch, the wheels cut, the mechanisms calculated, it’s going to require a design engineer…

When you speak of your motivation – in terms of why you are making the piece specifically like this, and not like, say, in a classic sense – it sounds like you’re making the works for the viewer or the visitor. That you’re trying to please.

I understand what you’re saying, but here… In this case, I’m trying to find a path that is both important to me and interesting for people to look at. If I go to an exhibition, as a viewer, I expect that the work will be interesting to me, that it will give me something. If I go see a movie, I expect that I will gain contentment, or an impression, or something… If I made something for me and me alone, then I’ll be damned if I showed it to anyone else; it would be a wheel of fortune for me and me alone. But now, I am, for example, calculating that it should be at a certain height so that it’s easily accessible. I’m making all of the handles comfortable for people to spin. Of course, I am thinking about things like that as well.

After all, it is a commission, or rather, you’ve been asked to participate. Would you have made something like that on your own, for its own sake?

I would have made something that is similar in principle. This is not one finished object; in a sense, it’s a continuation of my previous works. But talking about ‘pleasing’ others… [laughs]. I’ve spoken to some acquaintances about this piece in which you will be able to spin your own future, and they said that they will not take this opportunity, but will take a pass – they would rather not know…

Sketches of the “future scenarios” drawings for the Wheel of Fortune

They don’t want to know their future?

That’s right. This ‘pleasing’ is quite conditional – three of the five people I’ve spoken to have said they won’t be predicting their future.

I think people will want to do it.

Of course they will, but there’s something about it, I don’t know… Let’s say you spin a combination that shows a graveyard, a suicide bomber, and a world without life.

And they you have to live with this image in your head…

Yes, live with this image…

And you wait…

...and try to tell yourself – C’mon, this is only one of Drulle’s pranks…

...but if it really comes to pass?! [Both laugh] You’re right, though; it’s making me think twice about risking it. Physically spinning it – the action in itself – gives it some kind of meaning. It’s like you don’t believe in fortune tellers and similar nonsense, but if you go to one as a joke and listen to their prattling, afterwards, you can’t stop thinking about it…

Exactly; I also don’t believe in that stuff. I knew a woman who took these classes in Indian astrology where they analysed the time, date and location of your birth with computer programs. She also told me what I can expect and what will happen to me. If I told you I don’t think about it and have forgotten all about it, I’d be lying...I do think about it. [Laughs] This piece will be similar. But the work could have also not been. If I hadn’t been a part of the ‘country of the future’ exhibition, if I hadn’t gone to the residency in Croatia, if I hadn’t had a free summer in which to meditate on the riverbank – there would be something completely different; there would be a different exhibition in a different place, but the direction I’m heading in would have stayed the same in any case.

So Ursula Krinzinger saw your works for the Purvītis Prize and then invited you to go to Croatia? Is that the correct timeline?

She came up to me during the Purvītis Prize ceremony, shook my hand, patted my shoulder and said: ‘You can go wherever you want to, whenever you want to, and for as long as you wish!’ Truth be told, I didn’t recognise her – I didn’t know that she was Ursula Krinzinger. So I thought it was some sort of joke. [Laughs] Only later did I understand who I was talking to.

And that she was serious about what she said.

Yes. Ursula has her own residency programme; she has residencies in Sri Lanka, Hungary and Austria. Through these residencies, she gives artists the opportunity to live, work, and do what they need to do. I began to correspond with her on this, and she reiterated that this is no joke; she knows my works and the theme that I’m developing. For the Purvītis Prize, I had a piece about Latvia – on the abandoned houses in the countryside, how our environment is changing, how that is affecting our landscape and identity, all of the emigration, the whole subject… Ursula said that she’d like to give me the opportunity to go to Croatia, where her family has a summer house, and next to it, another one that could serve as an artist residence in which I could work. That seemed very interesting to me because Croatia, like Latvia, is from the Eastern Bloc, and we have that shared Soviet past; it intrigued me. Everyone has [historically] gone through here [in Latvia] – the Swedes, the Russians, the Poles – and it’s similar over there. But more recently, after the fall of the Soviet Bloc, they didn’t have as easy a time as we did. Ursula told me that the situation there is very similar with all of the abandoned houses and everyone leaving, and that I should go there. In September I first went to Vienna, to meet her; I spent a week there, meeting with gallerists in Ursula’s circle, finding out what they do, what’s going on, what the situation is like in Vienna now and so on. Ursula’s husband was the director of the Austrian Archaeological Institute – now he’s retired, but he spent his whole life leading archaeological digs in Greek and Roman cultural sites. He took me to Croatia, where we lived together for a week, and then he left me there for almost a month. I’ve rather recently just returned – about two weeks ago.

Drulle's residency in Croatia

So what did you do in the Croatian countryside?

I lived in the very north of Croatia, here [points on a map]. This is Slovenia, here’s Italy, and this is where I lived in the mountains, in a place called Kuberton. On very clear days, I could see Venice through binoculars.

Now that’s hard to believe…

Yes, it’s 400 metres above sea level, and Ursula’s husband had very powerful binoculars. I couldn’t see the tower itself, but I could see the lagoon where all of the ships come in. So, that’s where I was, and I had a bicycle so that I could get somewhere. It was a question of survival, too, since in the mountains there aren’t any shops where you can simply pop in when you need something. Everything was rather far away, but I managed to get everywhere by bike. They have very many tiny churches, a perplexing and truly unbelievable amount; I noticed that often times these churches had very strange writings on them, of the kind I had never seen before. I saw these symbols and wondered about the culture and its peculiar identity. I tried to figure out what it was and where it came from. It turns out that in the 9th-10th centuries, when the famous monks Cyril and Methodius had come to Croatia, they decided that Greek and Latin letters won’t do for translating the Bible into the language of the Croats, so they thought up a new alphabet called Glagolitic. That’s the alphabet used in those writings on the churches. Some of the letters are recognisable. The monks decided to introduce this alphabet in the 9th and 10th centuries, and it held on for one thousand years, up to the end of the 19th century. It’s not like it was used everywhere and always, but it was used for church business and rituals. But this whole area, despite the use of this alphabet, was under Venice’s rule. The Venetians really had them under their thumb; life was much harder for them there than for us here. The Italians lived in Venice while the Croatians lived in the countryside, worked the fields...they didn’t have any opportunities, there were no schools… After World War One, when Mussolini was in power, the Italians increased their oppression of the Croats. They forbid them from gathering, from opening schools, clubs or associations, and everything had to be in the Italian language. As we know, Mussolini’s side lost in World War Two, and then the Italians had a tough time. As I said, I lived in Kuberton. At some point in the 1950s, the Italians were simply asked to leave; around 350 thousand Italians left Croatia. Between 1948 and 1953 most of the Italians had left. Only a few lingered on, but the situation was made so bad for them – they had no pensions, couldn’t make a living for themselves, and eventually they all left. And that was why they had so very many abandoned houses, more than we ever did in Latvia – the Italians packed their suitcases and left their houses, and there weren’t enough Croatians to fill them. The houses were simply deserted. I began to wonder what I could do with this, and that’s how I came up with this study. The Italians that had ruled there from Roman times up until the end of the 19th century had built all sorts of cultural buildings and churches, and I noticed that all of these churches had what are called biforate windows – windows with two arched lights (also called a Venetian arch and a symbol of the city). I spent a month riding my bike and trying to photograph all of the churches with these biforate windows, or bifora. The whole coast was ruled by Venice, and there you have both Croatian culture and Italian buildings.

Using my photographs, I tried to draw 200 church bofira from all of the churches that have these two windows. It’s like a research study of mine. I don’t have all 200 in these pages here (I still have to finish them) but there are, in total, around 200 such churches in the Venetian zone of influence. My artwork will be something like this… There will be a cabinet with the pictures of these bifora...the visitor will be able to arrange the pictures… This is the history of the Croats, but the cabinet will have the option to be turned around, and then you will see the Croatian writings on the Italian churches.

Latin and Glagolitic inscription near a church

How big will the cabinet be?

Around two metres. It will be transparent, you’ll be able to… Physically, it will be like you see here. These are all of those Italian churches. The 200 drawings will be placed in like this. And you’ll be able to build it how you wish, like putting together a mosaic.

Biforium windows in photography and in artist's sketches

These panes are empty at the start?

Yes. I’ll put in about three at the opening, but the visitor, the viewer… Since the Croats and the Italians were having it at each other, and they couldn’t divide anything and were killing each other left and right (much worse than we ever did with the Russians), the visitor will be able to turn the cabinet – here is the Italian side with the Italian history, and here is the same thing but with Croatians… It’s interesting over there, all of the village and city names are in both Croatian and Italian. This is what it looks like in the Croatian language. They don’t write like this in everyday life; it’s like Latvians getting tattoos of our ethnographic symbols – the Croats now get tattoos of these letters.

Are you going to exhibit this in Vienna, in Ursula’s gallery?

Yes.

When?

It should be this winter, at the same time as the wheel of fortune. This is, in large part, about the past, because Glacolitic was used for a thousand years. The last religious texts were written in Glacolitic. But in the case of the churches, the last church with those two windows was built before WWII, when everyone was moving away. So it’s like a finished story.

So this is what you did in Croatia.

Yes.

Anything else?

I rode 2000 kilometres by bicycle, with a ten-kilometre vertical climb.

It sounds like you came up with the idea while there, that is, you arrived quit clueless as to what you were going to do and make.

Completely. I was like a blank page.

Inspecting churches in Northern Croatia

You didn’t worry about not being able to think of anything?

No; I had a vague feeling that… Actually, I tried to empty my mind of any and all preconceptions, stereotypes and expectations of what I might experience there, so that I’d be free and untethered. That’s also why I was placing great hopes on the bicycle and my observation skills. Ursula’s husband, the archeology institute director, was a great help because he spent a whole week taking me around and telling me about what had happened there, showing me the abandoned houses. And then I started to notice the unfamiliar letters and the churches.

That’s great. Have you drawn these pictures from your photographs?

Yes. The proportions are correct, but the scale is not true.

Are you content with the month you got to spend in Croatia?

You know, I posed this question to myself… Why do I even create art? What is my objective, and why? Because I could make much more money more effectively doing something else; I could also express myself more effectively… But I somehow concluded that, in my case, art gives me the opportunity to meet interesting people and everything that comes along with that. Also, it allows me to somehow clearly sense – to stiffly see – how fragile and non-fragile our world is because living our regular lives, we don’t see that; when you go out of your routine, you see everything with fragility and sensitivity.

Fragile in what sense?

In the sense that, these same Italians lived with the Croats for one thousand years, and suddenly click, and the system falls apart; in one day’s time, 300 thousand Italians packed their suitcases and ran away. The whole thousand-year structure fell apart.

Abandoned churches

So, your answer as to why you create art is because it’s a chance to meet interesting people and to feel the fragility of the human world.

Yes.

Wouldn’t it be easier to not be aware of that? Why is this important to you?

Yes, of course it would be easier. Ilona Brūvere once asked me what does freedom mean to me, if freedom is important to me. I answered that I think that freedom is a very heavy burden, that it is very hard to carry this weight of freedom, and that there are very few people who are ready for that kind of freedom. Here’s a banal example: if a person wins 100 million in the lottery, theoretically, they now have the opportunity to do whatever they want; but there are enough stories and studies proving that things don’t end well for them. That’s why I believe that freedom is a heavy burden. It’s much easier to live without freedom, otherwise you have great responsibility and you have to make very serious decisions about what you are going to do with your life.

But you’d rather take his heavy burden upon yourself?

On the question of freedom… I’m not quite sure where this freedom begins and where its boundaries are. Because I surely am not free – I have a job, I have the school here, I have responsibilities, I have to pay bills. That is not freedom. But if I didn’t have to pay bills, or go to work, if I could just get up and the whole day would be mine in which I could do anything, I don’t know…

No one’s going to shoot you if you don’t do these obligatory things…

[Laughs] Definitely not, but I will fall out of the societal structure because bills do have to be paid, and to pay those bills you have to do everything else, which means devoting time and attention to earn the money you need… That’s why I chose to do this residency, and I was lucky enough to meet these fantastic people. And because I saw this strange and unusual power and fragility upon which we all walk, as if on the edge of a knife; every so often we fall off, but we get up and continue walking along this knife’s edge. The feeling is kind of unusual and weird...the fact that we can walk along this knife’s edge, and that now, in the 21st century, we still continue along it.

And art has helped you to understand this. How has your life changed since you understood this?

[Thinks for a long time] Well… [Continues to think for a while] Let’s say, if I imagine my life as a kind of web, like a spider’s web, and these experiences make this web more complex, richer, more colourful, and let’s say if I sit in the middle of this web like a spider, then whichever way I turn, there’s a thread that will take me somewhere… Every one of these experiences is a thread that takes me somewhere. You could say that twenty years ago, the web was quite empty – I was making these little sculptures… I remember when I was studying at the academy, I was, of course, happy; I was making my art, I knew three sculptors, I tried to copy them and I was relatively happy...but how my life has changed since then… It’s become more interesting and complex – every which way you turn, there’s a thread that takes you somewhere. Something like that.

But you said that art helps you meet interesting people. Doesn’t that imply that, in the art world, the concentration of interesting people is much higher than in other fields?

I’m not thinking of specifically artists. Art helps you meet the kind of people that have sunk into the building of their own parallel world. You could say we’re living in these capsules of like-minded people, and these capsules don’t overlap all that often. My friends – my circle of friends and family – are like a bubble; I live in this bubble, and all of these other, surrounding bubbles don’t cross. But every so often, when I’m faced with the opportunity to travel somewhere with an art project of mine, I have a chance to meet up with another bubble. It’s like if a fish living in an aquarium had the ability to understand that there is something beyond the aquarium, and you can experience it for a short while and then return. With these interesting people, it’s like you look into their bubble, have a look around, and then return; but that is your new thread. Yes, the main thing is to meet people, not artists specifically, maybe even people who have no connection to art, but who have built their own small world in which they sail around. I, as an artist, sail around with my own strange things; I build my own little world, and it’s important to me to create a work of art that is not static but which can link me to something else. I sail around and meet people who are also sailing around. For example, Friedrich Krinzinger, the director of the archeology institute with whom I spent a week in the mountains… This may still be a fresh impression, but to spend a week with a person who has spent his whole conscious life doing Greek archeology digs, whose whole life is Greek and Roman culture, and who sees our life, events, and environment through the prism of what happened back then in Greece... Everything that’s going on right now, he translates back to Greece and Rome. For instance, he saw my wheel of fortune and how it predicts the future, and, of course, he immediately saw the Oracle of Delphi in it; because to him, that’s more alive than anything else. It’s a completely different world that really doesn’t exist for me. But to spend time with a person who, if he can’t find the right words, chooses to switch over to Latin because that’s easier for him… That was a great opportunity for me.