Everything I Wanted to Tell but Could Not

A conversation with the Russian artist Andrey Kuzkin about performance art, the truth and things that give him strength

Alexandra Artamonova

18/12/2017

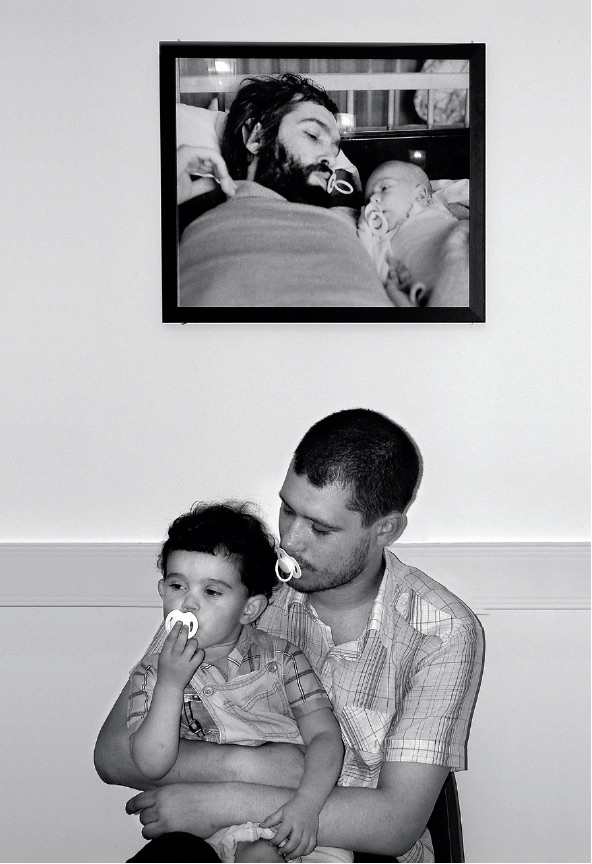

Nine years ago, at the ‘Halt! Who’s There?’ exhibition, part of the Moscow International Biennale for Young Art, a young artist fastened one end of a long rope to a peg in the middle of a pool filled with liquid concrete. After tying the other end around his waist, he entered the pool and waded this grey, slowly solidifying life for several hours. Andrey Kuzkin gave his first public performance the title ‘In a Circle’; it was followed by a string of others. The chronology is somewhat arbitrary, but the events all took place between 2008 and 2012; the artist: drew a continuous line on a gallery wall; carved the phrase ‘What’s this?’ on his own chest; modelled human figures out of soft bread, water and salt ‒ big ones and not so big, on his own and with prison inmates; chose spots in the country and in the city, stripped naked, buried his head in the ground and held this upside down pose as long as he could. Right, so what else? He hung a black-and-white family photograph (he, as a baby, in bed with his dad, both sucking on a dummy) on a gallery wall and sat down next to it holding his own child ‒ the two of them also sucking on dummies. He found a pond in a village and submerged a board inscribed ‘everything I wanted to say but could not’; tiny fry and bigger fish were swimming around it. In a word, he worked a lot. When Kuzkin started to feel tired and realized that he had maxed out, he switched to other things. He gathered all his belongings at the studio, took off everything he had on, packed the stuff into metal boxes, sealing them with solder, and sort of started everything afresh, with a clean slate. He stood on his head again, modelled human figures, lived in the forest, wrote fragments of his biography on a concrete fence, tried to speak of things that are on most people’s – if not everyone’s ‒ mind: of death, of vicious circles, drudgery and senselessness. Some of these works brought him prestigious prizes, from the Kandinsky Prize to the Innovation Prize.

September 2017 saw some of Andrey Kuzkin’s works included into the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery – a rare event for a Russian performance artist. We spoke with the artist about what is happening to performance art in Russia, about crisis situations, compromise, the truth and what gives him strength to carry on.

Andrey Kuzkin during his performance at the World exhibition. 2013

There is, nevertheless, a fact-based reason behind our conversation. As a donation from the Cosmoscow Foundation, the Tretyakov Gallery recently added to its collection a number of your works: the ‘All Ahead of You’ installation, accompanied by the video documentation of the performance (2011); the video documentation of the ‘In a Circle’ performance (2008) and the documentation of happenings and performances that were part of the 2006‒2015 ‘Right to Life’ project. This is a completely new experience for the Tretyakov Gallery: for the first time, its collection includes performance works by a young Russian artist. In fact, it is an interesting precedent for a museum institution of this kind, because performance is not collected in Russia in any coherent manner. I wonder ‒ how was it that the whole situation came about and what sort of experience was it for you?

The story with the collection is actually the end result of the goals and objectives that I had set for myself. Naturally, I did not have the Tretyakov Gallery in mind as the museum where my works would end up ‒ no, it just happened that way. But I had long been concerned about the subject of a personal archive; I was concerned about what remained there when the performance was over and what was the form in which information about it could be passed on to be comprehensible for a wider audience. To put it crudely, it was like a giant cesspool: a huge amount of unedited video and photo material, texts and so on. The whole thing needed to be put into some sort of order. I came up with the following concept: seventy panels, each of them featuring a picture and a text; each of the texts opened with the words ‘A man...’. So these panels were among the works that were shown last spring at the ‘Right to Life’ exhibition at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art in Yermolayevsky Pereulok. They lined the walls on three floors of the museum building. Together, they are my autobiography.

Andrey Kuzkin. Does Not Matter. Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 140 cm, 2011

So basically, you did two things at once: you tidied out your archive while also museumizing it at the same time.

Yes. And also made an attempt to tell about what I do in a plain and intelligible language, in other words ‒ promoted my work; it was for this reason that I chose this ‘bookish’ approach. On the whole, though ‒ I’m not sure if you’re interested in nuances of this sort or not ‒ there is a lot of discontent with myself in me, a lot of disapproval of myself. And I used to have a completely different approach to exhibitions. As a rule, I never asked anyone for anything at all. I only took part in exhibition projects when I was invited. And now, for the first time, I decided what I wanted to do. I approached them with the curator Natasha Tamruchi, bringing a project that I had come up with myself and that was already 80 percent ready, and asked them to host this show. As a result, the ‘Right to Life’ project brought me the Kandinsky Prize in the main category, as well as the Innovation Prize for the identically-titled book published as part of the exhibition project. As for the fact that the works ended up in the collection ‒ that’s the finale of the whole thing, the cherry on the cake.

Another thing completely ‒ why did it happen this way? Perhaps because I had made the correct choice of presentation for the material. I’ve always said that my works address as general a public as possible instead of a narrow circle of specialist viewers. And the poster-like approach that is present in this project ‒ these simple descriptions like ‘a man went and did something or other’, which are reminiscent not so much even of descriptions as of ordinary captions to photographs ‒ is not only justified but also convenient. Because the modern man is conditioned in such a way that he does not assimilate large texts; he needs a picture and a single sentence that explains what is it that’s shown in it. It’s also possible that it happened because of the simplicity of my works, which mostly touch upon the universal subjects of human existence that are also present outside art. Topical political subjects are significantly less represented here, which means ‒ no sex, no politics, no religion. It does not mean that I don’t work with these subjects. I do, but I do it in a veiled form. And it’s not a secret to anyone that it’s not only in this country that these subjects are not easily accepted for exhibitions ‒ it’s a pretty general trend. I suppose that I was picked by the Tretyakov gallery for this reason, among other things.

As for the fact that some oligarchs paid a certain amount of money for it... So apparently they like what I’m doing. It should also be noted that, until now, I didn’t live on money earned by selling my works; I lived on the money of these, relatively speaking, oligarchs, who awarded me money prizes and so on. Why does it happen? Because, presumably, these people do not feel fulfilled in their everyday life and they look for this satisfaction of the soul in various things: it’s the church for some and charity for others; some people help hospitals and sick people, while some spend money on contemporary art. This is the system that exists in Russia ‒ for the time being, at least.

Project All Ahead of You.

So how did you answer the question of what remains when a performance is over? And another thing I find interesting ‒ would you say that your ‘All Ahead of You’ project in 2012, when you gathered all your things from the studio and put away in dozens of sealed metal boxes for the next 29 years, was also a similar attempt of archiving both yourself and things that are around you?

Yes, you could say that. It was simply the way I solved this problem for myself at the time. Regarding the question of what remains... Feelings remain. Right now I am feeling quite empty inside, because my works are all out in the public domain and have become something different than they were before. On the other hand, the goal that I set myself has been achieved, and it means that I can calm down a bit, doesn’t it? That’s what I decided for myself ‒ that you must give away everything you do, give it all to people, because only they can tell whether it is something of value or not, whether it’s worth preserving or not. Considering the limits of my own life, my own time, I cannot preserve it all, and neither can my family; for this reason, I give it all away.

At the same time, a sense of depletion, constraint and generally something dead does not leave me. Because you cannot change a single thing in that archive any more, and at some point you realize that the whole thing has ended up somewhat flat and silly ‒ that this vast span of coverage has somehow detracted from the depth of the works and, as a result, you have, to a certain degree, become simply a hostage to the situation. I actually think about it all the time, because I find myself at crossroads at this point. I used to feel that I was above the situation: I played games with museums and galleries, I laughed and said thatit was all just a matter of chance whether your works had ended up in a collection or on a rubbish dump. Whereas now my works are at a museum, a certain amount of money was paid for them, and I am once again pondering the eternal question of what I should do next ‒ and how. I need to think up some sort of future life for myself, a different scenario and a new strategy, because everything I had has already been completed and exhausted and I no longer find it interesting. Making random exhibitions is also boring. At this point, I only see one more or less comprehensible route in front of me, and that is taking up plastic arts. I made some notes for myself, and one of them says that, among many routes, one of the options is indeed going big ‒ in the sense that a ‘big’ artist uses big budgets and make big museum projects. However, that kind of art exists within the institutional framework, which is something I have always tried to escape from. In a word, I am doing some thinking now.

And I have serious difficulty gestating this idea of a big museum exhibition: there are constant disruptions, I’m always distracted, and I lack courage for projects of this scope. In addition to that, there is this sense of fear and deceit everywhere... Look, the word ‘truth’ means an awful lot to me. I genuinely believe that there is something behind it. We can only have a sense of truth when we come in contact with it. Either it’s just my current mental state or the mental state of the public in general, but on the whole, I am very much bothered by the sense of untruthfulness and fear in which we all seem to live.

Everything There Is, It’s All Mine. Performance by Andrey Kuzkin at the opening of the Berlin Biennale, 2010. Top photo: Uwe Walter

And yet ‒ what’s next for you? Your art practice sees you work in many different media: performance, printmaking, sculpture. Which visual language do you find the most adequate? Could it be performance once again?

It probably could. But again, I have certain misgivings. Until very recently, I had a plan, which I’m still going to realize one way or another. I was going to make a big exhibition of ‘bread art’, namely, sculptures, installations ‒ both new and old, and then give it away once again. A heavyweight material project that would demonstrate that Kuzkin does this sort of thing as well. But the thing is, all this demands great material, physical, financial and temporal resources, and I do work on it, but I am taking a risk. I’m not completely sure as yet if I am going to succeed, and if I am, then ‒ where and with whom. This is, as I said, the traditional route. Nevertheless, I do know that I will still be doing happenings and performances, including ‘silent’ ones. It’s just that the place where I used to do it is simply being destroyed. Trees have been cut, something has disappeared, and that does have a certain impact on the whole thing.

Performance Together. Fabrika CCI, 2010

Quite often an artist is associated with a certain work of art, not necessarily his or her hallmark piece, more likely ‒ one that is the most memorable, most reproduced by the media. Look at Kulik, for instance ‒ that’s the one who pretended to be a dog. Osmolovsky ‒ the man who laid out the Russian profanity ‘khuy’ on the Red Square using the bodies of other people. Brener is the one who was swinging boxing gloves on Calvary and challenged the first president to a fight. Kroytor ‒ that’s the girl who was standing on a pillar. And you ‒ you are the guy who was walking in circles in concrete. What do you think about that? Do you find it annoying?

No, I don’t. In my biography, there have been a number of moments when I could have and should have done one thing and one thing only. If somebody associates me only with walking in circles ‒ so be it; it doesn’t matter one way or another to me. It’s just that the me in the concrete ‒ that’s the me familiar to some people. To others, those who are younger and have no idea of whatever happened back in 2008, Kuzkin is the guy who stands naked on his head in the middle of a landscape of sorts. A curator at the Venice Biennale said: ‘Ah yes, Kuzkin, a one-work-artist.’ So what do I do with that? So you see, the whole thing is very volatile and subject to change depending on the promotion of one work or another.

I won’t lie, I was not at all happy that people only knew me from a couple or so of my works. And at the ‘Right to Life’ exhibition it was important for me to show different things: seventy projects are presented there, and some of them may perhaps not play as important a role on their own as when they are all brought together. I think a lot about what I did back then, several years ago, and what I do now – I analyse the situation. And then some of the meanings get annulled to an extent, and often enough my personal freedom is limited to telling myself: I have already said my bit on this subject, I no longer find speaking about it interesting. Faith is important to me; not in the religious sense but as a state of feeling confidence and truth inside yourself when you are doing something. However, currently this self-reflection has reached the level when I catch myself thinking ‒ what place is this drawing going to take in my biography? And I don’t drawright now. I envisage the ‘bread exhibition’, which can end up very powerful, and this visualization of the future gives me strength to do something. I model these bread people myself; there must be lots of them, and it’s a long process, because I cannot hire people who would do it for me. So you’re sitting there shaping these figures, doing this mind-numbing work, and at the same time, you’re simply torn apart by some sort of emotions inside. And yet I don’t want to be associated with performance alone.

Speaking about even longer-term projects, I would love to make a big show of paintings and prints. It is a serious plan that I will be able to make come true if everything is all right. But the plan can also go to pieces, because everything is actually not all right.

Exhibition Remains at the Anna Nova Gallery. 2011

What else is important to you in a work, apart from the truth? Impact? The thing you mentioned in an interview a few years ago ‒ the fact that the piece makes a striking impact and immediately hits the vulnerable spots?

This is something to give some thought. I wouldn’t like to reveal all my cards right now, but there are three words going round and round in my head all the time, and I have no idea how to visualize them. These words are ‘lies’, ‘fear’ and ‘truth’. These are words that have constantly been with me for over a week and describe what is happening to me. These words are the truth for me, and the truth brings peace. I am thinking about what I should do with them, in what form to present them, but haven’t come up with anything as yet. I have certain ideas, but I don’t find them satisfactory.

Let’s talk a bit more about performance art. Now, here is the thing that I find intriguing: it seems that the life cycle of the Russian performance artist is very short ‒ five years, ten years, fifteen years at best. Off the top of my head, the only Russian artist who worked in performance consistently and practically until the end of his life was Mamyshev Monroe. If we take the artists who started in the 90s or the early noughties ‒ it’s Kovylina, it’s Osmolovsky ‒ we see that that not a single one of them is practicing performance art as such. What they do is open schools, recruit disciples and teach some sort of classes dedicated to moderately radical body art practices. How do you think – why does it happen?

Yes, it’s an important question. And I’ve asked it to myself many times, working on one project after another, and I think that I’ve found the answer. It’s just that, if you work in public performance, each of your pieces has to be more powerful than the previous one. That’s the rule of the genre. Yes, there are exceptions, like Andrey Monastyrsky and Collective Actions, who, it might seem, have been doing the same thing forever. However, their work is different ‒ it’s intellectual, non-publicity-related; you could describe it as laboratorial even. But when someone does public hardcore things, sooner or later they reach their limit, and when that happens, they have to either die, or come up with a way out of the crisis situation in which they have found themselves.

It happened to me. Look, prior to the project with the metal boxes I had been working a lot; I did things, constantly escalating, escalating, escalating – and that’s it, I maxed out. And then I took everything that was around me, put away in these boxes and sealed them. And this gesture was like summing it all up, drawing a line under the whole thing. After that, I couldn’t understand what to do next, where and to whom to go. At the time, I had a contract with a gallery; theoretically, I could have calmed down, become a commercial artist, lived my life modelling these little people out of bread (they sold well) ‒ basically, become exclusively a ‘bread artist’.

And yet I didn’t want that. I left for the forest and started doing forest performances, started searching for myself and searching for strength to go on, because I felt completely lost. I no longer knew who I was, what I was doing and for what. This lasted from March 2012 through late 2015. I practically did not take part in any public exhibitions for three years, during which time I dedicated myself to internal work or work that cannot be seen by everyone. It was a powerful and interesting experience, but then that, too, ceased to satisfy me. It is a never-ending sine curve: you hide from publicity in your basement, then come out of it, then go back again, and so on. And yet this practice, when I was doing things related to my childhood experiences in places where I had spent my early years and in places connected with my personal memory or the personal memory of my family, gave me strength to live on. At that particular moment, there was truth in all that. As soon as I articulated it and said out loud, the truth was lost.

As for the disciples, I totally understand why they are doing it. It is a very simple way out, after all: you humour your own ego, because all these young people look at you as some sort of Master, you draw energy from these young people, and in addition to that (and it’s important) you are also paid money for it. This is a relatively simple way of earning a living, and not in contemporary art alone. But this kind of way out does not satisfy me. I don’t think that I can teach anybody anything.

Bread Man sculpture from the Remains project (2011). Bread, salt, PVA, metal, 97 x 45 cm, 2011. Photo: annanova-gallery.ru

This is already a matter of ethics: how do you, in the situation we find ourselves in currently, speak about what to do and in what way? How do you work with your own body and emotions, and what do you aim to tell through it?

Many people will probably take offence, but I do see a certain weakness in this whole teaching thing. I am not sure how old you should be to presume to teach anyone. Although many great artists did have their schools, their students, their workshops. As for me, I can tell people about myself, my experience, my emotions, but as for guiding anyone anywhere – that I cannot do. Arseny Zhilyayev asked me five years ago: but where are you leading people? To which I answered that I do not attempt to lead anyone anywhere with my actions; I’m just asking myself questions and answering them; I set myself tasks and solve them. I still haven’t made sense of myself. When I finally understand for myself what the truth or at least verity is ‒ then we’ll see.

All right. Now I will take the liberty to propose the following consideration. I believe that one of the characteristic traits, the generic features of Russian performance art is narcissism. Furthermore, that the ones most prone to that are the so-called ‘radical artists’, the likes of Pyotr Pavlensky, and the artists who in their performative practice focus on internal mythology or, in your words, ‘universal human problems’. The narcissism of Pavlensky lies in this supremely personal confrontation: ‘I versus Lubyanka’, ‘I versus this state’ or, more currently, ‘I versus the System’. Speaking of the artist Andrey Kuzkin, in your case it lies in confrontation with yourself: ‘I versus myself’. What would you say to that?

There’s nothing to think about. I would agree: yes, there is that, too. Hmm, I don’t even know what to say, because that’s exactly how it is. It would be interesting to discuss the causes of this narcissism. What is the reason behind it? Is it the lack of a hero figure, something that we all miss? Is it a lack of understanding? The fact that no-one hears what anyone else is saying. I don’t know, but it will be interesting to think about it.

Andrey Kuzkin. The Other Shore. 2008

And another thing: what is your take on how it feels to be a contemporary artist in the Russia of today? Is it easy? And what does it mean to be an artist here and now? Is it a sort of spiritual practice, an expression of a socially engaged position ‒ or what?

I can only speak for myself, I have no idea what’s it like for others. As for me, I would rather describe it as complicated, although I have never been anything else in my life. It’s quite possible that it’s much harder to be a paramedic on an ambulance... It’s different for everyone. Art can be, for instance, commercial to various degrees. It’s normal. I told you about my earnings, about being maintained for several years by the so-called oligarchs: they gave me the Kandinsky Prize and so on; now they’ve bought my works and donated them to the Tretyakov Gallery. I probably have more money right now than most people in Russia. Or, to be precise, I have more money than I used to have before. Is it easy to be an artist in this set-up? I don’t know. Easy. And you’re doing exactly the thing that you want to do at that.

Providing I don’t stage any radical political performances, I can show at any art gallery ‒ and they will gladly accept me. I don’t want to – that’s a different matter altogether. There are no people around who would satisfy me, no art galleries. What is more interesting ‒ selling your works at a gallery or making a statement that will let your senses experience something completely new? I’m not sure if these two things are compatible. So I’d rather go on staging my performances in all sorts of open spaces. Another thing ‒ there is YouTube, there is Facebook. Everybody is an artist now; these are open platforms that haven’t been closed as yet and that no-one ever uses for their art. It’s just all sorts of bloggers who use them for their own purposes. And that’s just the way it is in democracy: we have our own little world here where we are the kings, but over there we exist for the general public. In that sense, Pyotr Pavlensky has left everybody far behind. I do sometimes find him lacking as an artist; some of his works could do with more depth, but what there is enough of is definitely courage. I don’t know if he will continue his practice or not, but in any case ‒ it’s not for us to decide who stays in art. You know, actually, I really believe that most general problems are the same for many countries. Incidentally, a performance of mine was banned in New York.

Why?

Because.

For the same reason as everywhere else. Why did they ban it in Lithuania? I recently came back from a festival in Kaunas where I was also not allowed to stage my performance, because a naked man in a public place automatically means a fine of ‒ I don’t remember the exact amount, EUR 200 or something like that. But I still did it. As for New York, it was at an exhibition entitled ‘100 Years of Russian Performance’, part of the Performa Festival, and the situation with the ban was exactly the same.

I did it anyway. There was this territory next to a Christian school or something, I don’t know. And that’s where I did it, I stood on my head naked amidst bin bags. Horrible. I don’t remember experiencing anything worse than that in the whole series.

But the fact is, it’s very hard to live in any kind of world if you’re disposed to reflect on the subject of your own activities: What is your background? Where do you get your money? What do you do in the context of everything that’s going on around you? If you want to be honest, your life will be very complicated in any country, because you are surrounded by compromise. Actually, speaking the truth is easy and it feels good. A person who speaks the truth is strong, whereas he who is cunning... I don’t know, surely he feels that’s something is not right and that he is a hostage to the situation, because he has children, he has a family, etc. There are, of course, some truly sublime people, the likes of [Andrey] Monastyrsky or [Victor] Alimpiev. They exist in some sort of internal world; they are genuinely not bothered about anything that’s going on. And I would love to live like that, but the element of reflection is too strong inside me. I cannot 100 % believe in what I do if I don’t put it into the context of what is going on around me ‒ not only in art but in life in general ‒ in politics, in the everyday life of my loved ones.

I tried fighting this: I went off into the forest, went far away on hiking trips, and it stopped worrying me when I was there. But as soon as I came back, so did these feelings. Yes, I can say that water was wetter and grass was greener in the past, and that’s true ‒ it really was easier to breathe. Breathing is hard now. Living in Russia is hard for me, and I can say that because I live here, and I know this country. But then again, it was hard for me in America, as well, although everybody can’t praise the country enough. I spent four days in New York; I was alone, I was no-one’s concern. I wasn’t allowed to do what I wanted, so I wandered around the city, where the rhythm of life is just crazy, where the competition is mad, where (I think), if you don’t work, you go under immediately. I somehow ended up in a park around 7 p.m. You know what the usual picture in our parks is like: mothers strolling with prams, jolly companies making noise on benches. Over there, everybody is running somewhere in their tracksuits or riding their bikes. I was gobsmacked. And right there, outside the park, there are buildings; the windows are without blinds and there is light inside. And you see how people inside exercise on their treadmills. It’s almost like they never stop. They love to work. The Chinese probably also do ‒ but what about us?

I recently read an interview with the director Khlebnikov who told about shooting a film somewhere in Russia. In a word, they needed to hire some workers and the pay was a thousand roubles a day (which is good money for those parts of the country). Nevertheless, the local people, while mostly unemployed, declined. And there was also a local farmer who needed his potatoes harvested. The man went to every neighbour and pleaded with them: not only am I going to pay, he said, but also give you every fifth sack of potatoes for free. No-one volunteered, so the farmer shipped in some Uzbeks. They harvested the potatoes, they were paid and taken to the nearest bus stop where the cops suddenly showed up ‒ started checking their papers and simply confiscated the money. That’s the way we live in this country. But I digress.

Not a single artist of the ones I know (and, admittedly, I do not have a very vast circle of acquaintances), of the ones I have spoken to about this, have the slightest idea for the sake of what they are working and where does it all end up. There is certainly no hope of a bright future in any of them. Youngsters, on the other hand, have this notion of contemporary art as something that is cool and currently all the rage. Someone comes to an exhibition, sees some sort of rubbish hanging on the wall with a price tag of several thousand euros and goes: oh cool, that’s what I want to do, and signs up for contemporary art classes. Those who take up art because of completely different needs ‒ there are significantly fewer of those.

Performance ‘In a Circle’. 2008

So now we are going to end the conversation with the question we actually could have started with. Why did you start working in contemporary art? Where did this need to stage your very first performance come from?

I graduated from the Moscow College of Printing Arts, I studied design... I also grew up in a family of artists: my dad was an artist, my stepfather was an artist. He was also the person who instilled in us the one thing that has probably played the most important role in our lives ‒ the urge to express ourselves through art. After my studies I worked in design; I tried very hard, came up with all sorts of things ‒ the fresh-faced eager chappie that I was. Eventually I realized that the customer does not give a damn about the things I was doing. So this sense of helplessness, of the senselessness of my existence gradually built up. Some of my friends, despite the fact that they have the mindset of an artist, work in design to this very day. They decided to settle for a compromise; I refused to do that. Sometimes you just lose any sense of fear that could keep you from saying or doing something – you just go and do it. You are fearless, and the world is your oyster. In a word, that’s what happened to me back in 2008.

And I also had this desire to find an answer to my questions and a feeling that everybody around me were talking about the wrong things. But where do you find the right things? Where are the things that speak about the stuff that I think about, that excites me, that does not let me live in peace? They weren’t there. They weren’t anywhere near me. And then I started making them myself. My first works, including the performance ‘In a Circle’, are about the absolute senselessness of my own life. You stage a performance about yourself, but you also presume that there are possibly other people who think about the same things; it’s just that they cannot or do not know how to speak about them. That’s how the whole thing started. And another thing yet ‒ a very important, intimate and dramatic one. It’s that I was ‒ and basically still am ‒ afraid of death. My father died young, leaving behind very few works... And yet it’s not even about that; it’s about realizing that I am finite. At any moment, I may cease to be, and everything that I hold important but haven’t expressed in any way will go with me. I felt that I needed to get done more, and I tried very hard to get done more. I drove myself hard. I have eased up on myself now, though.

Andrey Kuzkin at the opening of his ‘Affections’ exhibition in Voronezh in 2015. Photo: Evgeny Yartsev