His own story

An interview with Polish photographer Rafał Millach

15/03/2018

In February, the only exhibition space dedicated to contemporary photography in Riga, ISSP Gallery, opened its doors in Bergs Bazaar. The gallery’s programme emphasizes photography as a form of conceptual art representation, and in addition to exhibitions, will also hold artist-led presentations and discussions on this theme.

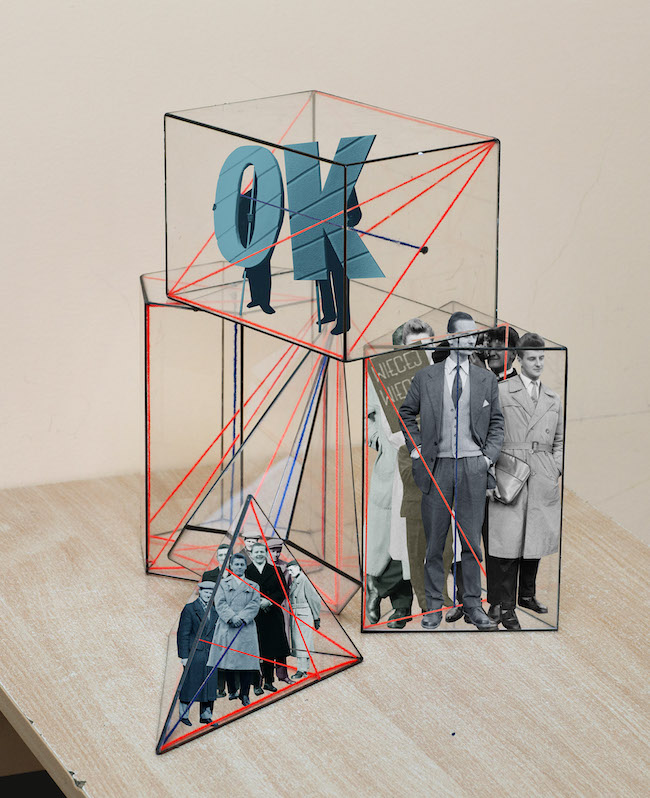

The first exhibition on view at ISSP Gallery is a solo show by award-winning Polish photographer Rafał Millach. Titled The First March of Gentlemen, it transposes historical reality into a present-day form. Millach’s collages reveal his thoughts on important events that took place in Poland in the 20th century, and his wish to keep history alive. Millach speaks about photography with great reverence, stressing its variety of meanings in the contexts of both contemporary and historic timelines.

When reviewing Millach’s previous work, it becomes quite clear that the works on view in The First March of Gentlemen in Riga greatly differ from what he’s done before. This is, of course, a gross generalization, yet I’m using it to point out that Millach has replaced his ‘pure’ photography style with collages that are almost on a level of fine art painting. The most important component of these works is the story, which, through personal interpretation, reveals the importance of photography at various times. Almost just as intrinsic an element is colour; it serves as an attracting power, as camouflage, and as a background. The teller of its own story.

Rafał Millach. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

The exhibition The First March of Gentlemen analyzes significant events in Polish history in a contemporary format. What inspired you to tackle this sort of theme?

First of all, I must mention that this project emerged from the Kolekcja Wrzesinska residency programme. The programme took place in 2016, in the Polish city of Września, and this exhibition is the result of the works and thought processes that were accomplished there. The goal of the residency was to depict the local city’s history as well as contemporary events. My artistic task, then, was to interpret this small town in my own way. While I was there, an important event in Polish politics took place, namely, the government changed. Ans Polish society began to actively protest by rejecting the politically incorrect decisions being made by the new government. You could even say that at this time Poland was in a constant ‘state of protest’. I felt that it was my responsibility to participate not only as a citizen but also as an artist. For my project, I decided to turn to a combination of various metaphorical historical layers. This project is like a story that can be divided into several chapters. The first and most important part is the division of two existences. Namely, it is about the relationship between freedom and peace. The other layers in this story are directly dependent on this relationship.

The First March of Gentlemen. Publicity photo

Can you expand on what you mean by these ‘layers’?

The first layer refers to the infamous Września children’s strike which took place from 1901 to 1904, more than 100 years ago. At the time, this region was a part of Prussia, and the school children and their parents protested against the active Germanisation and refused to learn from books in the German language. The students were also protesting against the physical abuse that was being inflicted by the teachers. The second layer is related to the archive of Polish photographer Ryszard Szczepaniak. He documented Września starting with the 1950s – in effect, the post-Stalinist era. The time that Szczepaniak reflected was despotic, but the people and the environment which he photographed were in some special way removed from the oppressive context. Although he used symbols characteristic of the time – such as reflections of the military structure or civil society – he managed to do it in a neutral manner. He placed the subjects of his images in a very general, natural context. He kind of played with reality, staging various military scenes. That’s why in his pictures you can see soldiers firing at one another or aiming at themselves. Ryszard Szczepaniak had the courage to laugh at the times in which he lived.

He dared to use irony as a platform for creating art.

Exactly. It’s an ironic and humour-filled attitude towards work which, in its way, reflects a specific period in Polish history. The relationship between freedom and peace can also be seen in the context of the children’s strike. It is no surprise that in every authoritarian political regime there will arise a disposition towards making change happen. Often times it is achieved through protests; this strike was also successful. But this doesn’t mean that the time was any less oppressive – Poland was, after all, under German rule. But people regarded protestation as an opportunity to express their freedom.

The First March of Gentlemen. Publicity photo

You’ve been representing political and social events in your work for several years now. Your works are permeated with an individual interpretation of Eastern European society and the changes that have affected it in the years after the fall of the Soviet Union. How do you explain your interest in these themes?

I think that it is every artist’s task to react to what is going on in today’s environment. And right now we’re living in a very politically tense time. Consequently, many of the spheres in our lives and daily occurrences seem to have lost their innocence...even the opportunity to be neutral. Context is extremely important to anyone who works with the visual arts. The ability to communicate with the aid of visual forms is imperative to me, which is why it seems logical to react to and comment upon that which is going on around us.

Opening of ISSP Gallery and Rafał Millach exhibition. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

What does The First March of Gentlemen symbolize for you personally?

It is a manifestation of fear, need, and want, all at once. It’s like a metaphorical representation of society and time. It is my understanding of the previous century, of these specific events that I touch upon in my exhibition. Looking from today’s viewpoint, history can seem rather enticing; like a compelling story that seems simple and comprehensive to everyone. But actually, there are so many different layers hiding in this story and they’re not enticing or vibrant at all. They reveal history from a different point of view.

Is that why you use vibrant colours in these specific works? To engagingly manipulate the viewer by indicating the multi-layered quality of the story?

Yes, you could say so. In a sense, the colours are like camouflage. A very powerful form of cloaking that formally aims to infatuate us, but at the same time, reveals so much that is new and unexpected. As soon as we give in to this manipulation and spot the background of the story, we are also able to submit to analyzing the image and discovering the many layers that are hidden in every picture.

Photo: Kristīne Madjare

The works in the show have been created in the collage technique. This is your first time using this form of expression so broadly. Is collage, in your opinion, also a form of manipulation?

In this case, collage is the result of the creative process. My original idea was to work only with materials available from the archive and to not create any new images myself. We’re under the influence of image overload right now. But working on the project, I did also create new pictures, although the archival material was the foundation for it all. That’s why I chose collage. Later on, it was joined by a motivation to create a kind of imaginary space in which historical facts are interpreted on an abstract, metaphorical level.

In that sense, collage is a forgiving form of visual art – the camouflage I mentioned before also works much better within it. It is specifically these bright colours that make us feel at ease when we should actually be feeling discomfort.

You also work with documentary photography. As a photographer, is it more important to you to capture the reality in which we live, or to create this environment from scratch?

It’s hard to say; it seems to me that both approaches are equally important...if this sort of ‘capturing’ or representation of reality is even possible. Actually, everything already is the result of somebody else’s projection, which is why it’s hard for me to completely believe in the representation of reality as such. Even having worked in the field of documentary photography, I can no longer assert that photography can capture reality. That’s quite interesting because, in large part, we still trust photography and the images that it creates. I’d rather say that I strive to create or interpret that which surrounds me. I conceptually try to translate what I see into a visual form. I must say, however, that it always develops from a process of contemplation. It is the result of creative contemplation, but tightly linked with its context.

The First March of Gentlemen. Publicity photo

This a time in which practically everybody is calling themselves a photographer as they post their visual diaries on various social media. Despite this, you continue to place your trust in the printed book...you’ve authored several photobooks.

I’ve always perceived the book as being the most complete embodiment of my projects. I’ve been participating in exhibitions since I began working with photography, however, unlike my first projects, I now try to make the exhibition environment much more consciously deliberate. Moving an exhibition into a book is a very special process for me. In my last projects, I’ve distanced myself from showing personal stories and have instead turned towards studying mechanisms or systems. I’m interested in systems which people join against their own volition. A book is a special form of communication that creates the necessary intimacy from scratch. It’s a medium that respects the work itself; it gives it the necessary space and the opportunity to create personal relationships. I really like books.