Who's afraid of Cologne?

An interview with Christian Nagel and Saskia Draxler, the owners of Galerie Nagel Draxler in Cologne

28/05/2018

On the last day of this year’s Art Cologne, one of the events going on in the talks lounge was called ‘25 Years Ago: the “Wild” 90s in Cologne’. The speakers shared their memories about a relatively recent period in the city’s history: a time of change when, at least for a moment, the world shifted its gaze from Cologne as continental Europe’s centre of contemporary art to Berlin; a period of searching for something new, when an anti-institutional and anti-commercial spirit ruled over the city’s art and cultural circles; and a time during which, instead of producing new works, artists were much more interested in constructing their own personal narratives and inserting artists and art into the societal structure. One of the speakers there was the notable German gallerist Christian Nagel, who opened his gallery, Galerie Christian Nagel, in Cologne precisely in 1990, quickly becoming an important player in upholding Cologne’s image as an art metropolis.

From its inception, Galerie Christian Nagel concentrated on three pursuits. Firstly, as its founders readily admit, in creating a permanent ‘home’ for a number of well-known, important, and established contemporary artists and their works. Among Nagel’s long-term partnerships are the artists Renée Green, Andrea Fraser, Mark Dion, Michael Krebber, Cosima von Bonin, and the world-famous creator of feminist art, Martha Rosler. Another pursuit or objective of the gallery was to represent ‘mid-life artists’ who continue to work and are influential enough to still be creating the newest trends in contemporary art (this group includes the likes of Kader Attia, Michael Beutler, and Rachel Harrison). And lastly, in emphasising the need to look to the future, from time to time the gallery also works with interesting new artists, such as Egan Frantz, Christine Wang, and Luke Willis Thompson. Over the years, Nagel’s gallery has grown into a prestigious and internationally renown gallery that regularly participates in the world’s most significant art fairs. The gallery has four exhibition spaces now – two in Berlin and two in Cologne. The newest space, in Cologne, opened just this spring (April 18) during Art Cologne.

About ten years ago while in China, Nagel met Saskia Draxler, a philosopher and cultural critic from Frankfurt. They decided to join forces and become partners in leading the gallery, and since 2013 the gallery has been called Galerie Nagel Draxler.

When I first found their booth on the second floor of the Art Cologne fair, I was expecting to interview just Christian Nagel, the founder of the gallery. To my luck, Saskia Draxler also happened to be there and was able to participate in our conversation.

Saskia Draxler and Christian Nagel. Photo: Albrecht Fuchs

I understand that two days ago you opened a new space here in Cologne.

Christian Nagel: Yes, a new gallery, but it is our fourth. We have two in Cologne and two in Berlin.

How did you decide to open another one?

Nagel: We had been lacking a big space for some years now; we usually do two to three shows a year, and if it’s going on during the art fair or some other event, we’ve always had to rent big spaces to do our shows. But most suitable spaces are often already taken by others, and it is difficult to move around exhibitions, so we decided to make a new, permanent space that is open daily.

What made you choose Egan Frantz as the first artist to exhibit at the new space?

Nagel: We had already been cooperating with him for some time – he had a show at our gallery in Berlin in 2016. We already knew then that we wanted to show it to the public in Cologne as well. It was not specially considered to have him open the gallery, but it was good to have a decent, young American artist as an opener.

How did you come to meet him?

Nagel: We met him at Art Basel in 2013; we looked at his work, and we became interested. I went to see another show of his, I told Saskia about it, and then we decided to make a studio visit. After that, we finally invited him to our show.

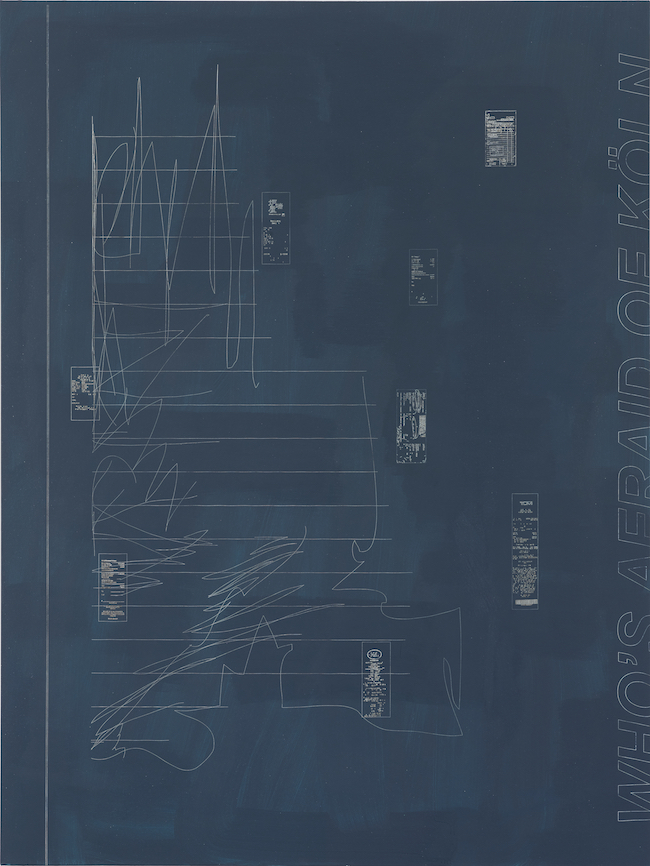

Saskia Draxler: His first show with us was in Cologne in 2014 and, you know, he immediately reacted to the city – he paid attention to where he was. The city of Cologne has great meaning for a young artist from the States because many important artists and ideas have come from here. So, to have Egan for the opening of the new space was actually a very good choice. His work is also, in a sense, related to the big painting tradition of Cologne. There is a painting of his in the show that says: ‘Who's afraid of Cologne?!’

When thinking about which artists to invite to the gallery, do you both make the decision?

Nagel: Yes.

What is that you look for when you’re on the lookout for new artists? And how has this changed (or not) since you started out?

Nagel: Our situation is not quite like that – we already have a rather long history with the artists that we show, and a lot of them have a considerable contextual and conceptual background. In terms of young artists, we try to find someone who has the same level of skill and talent...who are of the same quality as our long-term artists. So, we don’t really look for a new group of artists since we have enough artists to exhibit. But we do travel around the world, and if we see young people who seem interesting, we may consider inviting them to the gallery.

Draxler: It's not as if we are aggressively looking for new artists. The gallery has three generations: established artists that have been showing with Christian since the beginning, like in the 90s; then, I would say, mid-career artists, like Michael Beutler or Kader Attia, who are not – or where not – that well-known but are still in that age group. But if we find young artists who pique our interest, then we take a second look and perhaps give them a chance...because we also think that's a challenge for the future. Some of these younger artists, like Luke Willis Thompson, for instance, who had a show with us last year, they like the fact that we also show Martha Rosler and Andrea Fraser, because that gives them context, you see... For a younger artist, this is truly interesting – to be in the context of an established group of artists who first started to show with Christian, like Rosler or Fraser, or Renée Green of Clegg & Guttmann...

How many art fairs do you attend annually?

Draxler: Let's see... Hong Kong, Cologne, Basel, Copenhagen, Berlin...

Nagel: Eight to nine. Too many.

Lisson just told me that they go to about 16.

Draxler: Sure, they have more staff. We usually try to go ourselves – at least for the opening.

Nagel: But sometimes we divide the work, and only one of us goes.

(To Saskia Draxler) When did you join?

Draxler: In 2009 I joined as a partner, and in 2013 we changed the name.

How did that come about?

Draxler: We met after difficult times – after the 2008 [economic] crash. I wanted to start a gallery, but it was extremely difficult at that time. Christian needed some help, so he came around with a good offer, and I joined; we share it 50-50. We thought of leaving the name as it was because the brand can be important, but it was also a way to start afresh. And I think it was Ok.

Nagel: Oh, it was super Ok!

Draxler: For the number of shows that we're doing and the kind of business we run – a mid-to-large gallery like this one – we need... everybody! [Laughs.] All the help we can get. We have a team of ten to twelve people, and the two of us, but even so...we're always pushing the limit. [Laughs.]

View of the exhibition "Not yet no longer Speaking to the void, in spite of Prefigured monumental ruin." by Egan Frantz at Galerie Nagel Draxler in Cologne. Photo: Courtesy Galerie Nagel Draxler

How would you compare Art Cologne with other fairs that you attend?

Draxler: It's more civilised. [Laughs.]

Civilised? How so?

Draxler: If you go to Frieze London on a weekend, you see people knocking over artworks, coming with big backpacks and umbrellas and so on... In Cologne, you have a very refined and informed audience – people who know about contemporary art.

Are you both native to Cologne?

Nagel: No, I'm from Munich and Saskia is from...

Draxler: I was born near Frankfurt.

So the reason that you moved here was to open a gallery.

Nagel: Yes, in 1990.

How did you decide that you want to become a gallerist?

Nagel: I first had a gallery in Munich. I worked internationally, and when I was in New York, I asked: Can I show these artists at my gallery in Munich? And they said: ‘No. Munich is not an “A”-city, it's a “B”-city.’ I asked what is an ‘A’-city then, and they said – Cologne. It has always been clear that that is the case – Cologne and Düsseldorf have the academy and the fair, and people like Joseph Beuys and Max Ernst were always around this area. It has always been clear that, before all the ‘Berlin thing’ started, that this was a metropolis for contemporary art.

What were the historical reasons for Cologne becoming such a centre (for contemporary art)?

Nagel: One reason is Mr. Ludwig, of course. He came from Aachen. He ran a chocolate business about 50 km from here, but he also studied art history. However, he could not become an artist because he had to run his wife's business. But he did make a lot of money and he started to collect – at first, Picasso (because he did his PhD on Picasso). Then he started to also collect Pop Art, and more and more people ended up here...then the fair was launched in the 60s, and more and more galleries came. And in Düsseldorf, there was Joseph Beuys, and the academy with all of its students...

Draxler: The most important avant-garde gallery in Europe, probably in the world, started in this region – it was Konrad Fisher, who had a gallery which was basically just the entrance to his house – a hallway. His first show was Carl Andre. He showed American conceptualist art before they were known in the States, you know. Then there was the Wide White Space gallery in Antwerp, not far from here. It was quite a region for the avant-garde, and a lot of American artists first became famous here, and only then gained fame back home. The same thing happened with Christian's generation, like with Andrea Fraser – she had her first notorious show with Christian in Cologne, before she was famous in the States.

Nagel: Yes, things start early here.

Draxler: Basically, additional reasons were that there was money here, and the local bourgeoisie was interested in art...

Nagel: In the 60s, society radically changed with the ‘68 revolution and all that... People who were more established could not really change that much – they could not get hippies to follow them and respect them... But contemporary art was an instrument that the bourgeoisie could use to be modern, to be more open-minded. So, a lot of people who were more financially established started to collect art... And it was sexy, it was a party scene – it was also fun! It was a lot about intellectualism in radically new forms, which were not always easy to understand, you know? Beuys is not easy to understand. But there was also the other part – the part of ‘happening’, and of ‘opening’, and the social life...

Draxler: Maybe one of the historical reasons was that the German bourgeoisie wanted to be seen differently than just linked with its Nazi past. Because most of them had international relations (business and otherwise) and the contemporary art scene gave them an opportunity to be different.

Nagel: These people then went to New York, they met Lichtenstein and Warhol and others...

Draxler: And they also went to Russia.

Nagel: Yes, but later. First came Pop Art and the American influence.

Egan Frantz. Who's afraid of Cologne/Köln. Oil/acryl on canvas. Courtesy Galerie Nagel Draxler

[Addressing Nagel] You previously had an art gallery in Munich, but initially – what was the path that led you to become a gallerist?

Nagel: I studied art history, and I knew that one way to have a career is to work in a museum. But when I tried that, I realized that in a museum, you will always be suppressed because the curators and the staff will control you, and you will never be able to do what you want to do. I was afraid that if I worked in a museum, one day I would be told: Now do an exhibition on Clemente! But I don't ever want to do an exhibition on Clemente. [Laughs.] I want to do my own thing.

Draxler: There’s also an anecdote about you...

Nagel: Yes, that was when I applied to the Munster Kunstverein. I wrote a letter in which I described what kind of an exhibition I would like to make if I were accepted. All of the names I mentioned were already on the scene in the late 80s – not very famous, but they were known in the art circles. People understood that. They wrote me back: Thank you, but we decided to take on someone who has some understanding about contemporary art. [All laugh.]

[Addressing Draxler] And how about you?

Draxler: I studied philosophy and literature in Frankfurt, and at first I was interested in experimental theatre, but slowly but surely I moved towards the visual arts... But I was on a different side – I was writing about art and I was teaching. I met Christian in Beijing, where he was doing an art fair with his gallery; I was teaching at Central Academy of Fine Arts (Cafa), teaching philosophy and conceptualism and contemporary art to young Chinese students and artists. I switched sides – it was a challenge, you know, but I knew the gallery before I knew Christian, and I knew that he represents artists that you can have a conversation with. With this gallery, it was easy to switch sides.

It's a tough road, and sometimes I think I don't have enough time to read and write anymore. It's a very competitive environment, and it's gotten worse, you know... After 2008, we thought – maybe this is a correction, and maybe we can now go back to treating our colleagues better, show more solidarity... But the contrary happened. It's really, really tough. It's a very neo-liberal field to work in. And money has burned a lot of its charms.

What's holding you to the business, why do you stay where you are?

Draxler: We don't know what else we could do. [Laughs]

Nagel: We didn't study anything else, you know. I mean, we couldn’t open a car dealership or a bakery...