Suspension of Disbelief

An interview with Lithuanian artist Julijonas Urbonas

19/07/2018

A few years ago, the popular culture was literally overwhelmed with a new tendency of lifestyle, that was based on a very simple saying – you only live once (mostly used as an acronym “YOLO”, originated in the 1960s). This ideology of proper fulfilment in life became so influential, people began doing things they would’ve never done before. Sometimes this change of living – or the principle of yolo – was based on common things, like becoming a vegan or dressing more defiantly. But most of the time it was about putting your life in danger, pushing to the limits and exploring new opportunities.

Lithuanian artist’s Julijonas Urbonas’ projects balance between total absurdity and broad scientific research. For over a decade he has been working between installation and conceptual art, critical design, choreography and amusement park engineering. Being influenced by his father’s work as the director of an amusement park, as well as Soviet and post-Soviet ideologies, Urbonas’ art is a combination of personal, emotional experience and futuristic predictions. Since 2007 he is a PhD student in Royal College of Art in London and since 2014 he has been working as the Vice-Rector for Art in the Vilnius Academy of Arts.

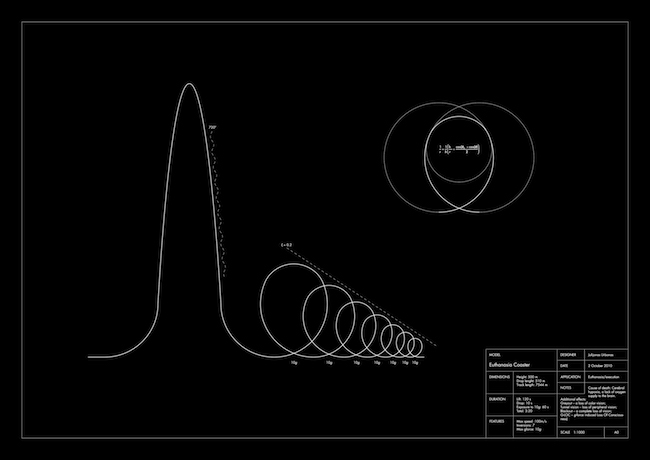

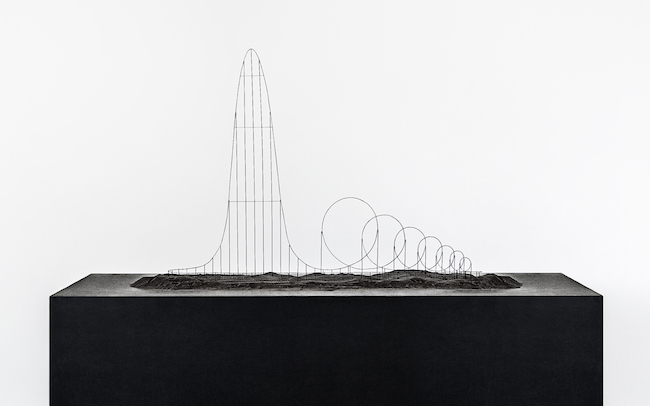

Theory in Julijonas Urbonas projects is as important as practice and scientific speculation. For years he has developed a specific theoretical baseline of his artistic activity, which he calls gravitational aesthetics. Gravity, that made possible the emergence of a human being, and gravity that can be outplayed. In 2010 he created Euthanasia Coaster – a hypothetic death machine in the form of a roller coaster. It wasn’t because of suicidal thoughts or any other depreciation of life, in fact - on the contrary, he created this object out of an interest for life and fascination about amusement rides. This project became Urbonas’ way of saying: “you only live once, so be careful what you wish for.” This object quickly gained popularity, was included in MoMA’s curatorial online project Design and Violence and acclaimed by international press. Euthanasia Coaster brought Julijonas Urbonas world fame (it even has its own Wikipedia page) and this year, curator Katerina Gregos has brought Euthanasia Coaster to the first Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art.

Julijonas Urbonas. Euthanasia Coaster, 2010

Julijonas Urbonas. Euthanasia Coaster, 2010

Why don’t you begin by telling a bit about yourself? Your artworks are mainly based on scientific explorations and might seem a little complicated for some part of audience.

Oh, I actually believe that my works are very easy to understand. First of all, you see a recognizable object.

But when you get to the concept…

Well then, of course, it gets more complicated but there is always a superficial layer that can be open for any type of public. Either for wide audiences or for very specific experts. You might think of a rollercoaster that kills the rider and has engineering, bioethics and many other layers taken from science fiction or set design. Usually, I develop such layers throughout many years while having contact with diverse audiences. Believe - the more layers you cover, the more likely it is that the audience will cry. You know, just like when peeling an onion. My practice usually has this multi-layering and for me it is a way to get to the complexity of a matter an opportunity to meet certain people who are experts of different fields. For example, biology or physiology. When you combine all the knowledge you get from these people, you become a multi-expert, a one-man orchestra, and from then on you can begin to construct these layers. But, anyway, I get the idea of your question…

I was wondering about the background of your art – actually it’s a topic that always interests me. How did you become fascinated about scientifically oriented art, amusement parks, engineering...?

The key story is that I spent all my childhood and youth in a small Soviet amusement park in Klaipēda, whose director was my father. At that time, he considered kindergartens as kind of like communist indoctrination camps and wouldn’t let me and my sister go there. Instead we were babysat by ride operators, park managers, public programme curators… He was running the amusement park for 10 years, so I was physically and intimately related to it. By then I had this professional misfortune that I never liked to ride the attractions.

Was it because they were all around you?

On one hand the park’s rides seemed quite boring to me. I was dreaming of Disneyland which is much more stimulating. The idea of Soviet amusement parks was a little bit two-sided– all the decorations were made in such way that they would facilitate communism. The tandem of visual agenda and various events were supposed to soothe the labour power and prepare children for their bright future. My family was conscious of this and I guess that it had some kind of an effect on me.

So, metaphorically speaking, you saw the dark layers of amusement parks.

Yes, and I also felt the stagnation of creativity there. It seemed boring to me so I became more interested in different kinds of attractions. I think that amusement parks are really interesting in the terms of aesthetics – there is no artistic form or non-artistic form that would generate such an addiction or use the trajectory of a moved human body as a key means of expression. The idea of amusement parks is based on sensual, psychological, social, political, economical layers. Everything is somehow interfiled in the same narrative and there is no other art form that has the ability to accomplish this.

I actually wanted to ask you, if in your opinion, there is an equivalent to an amusement park in art or design?

I’ve been searching for almost 15 years and still haven’t found anything similar. That’s why I came up with the idea to develop my own kind of creative methodology, which is based on what I call- gravitational aesthetics.

The idea is based on so called ego-motionalaesthetics (Ego-motion or self-motion refers to the body’s motion in space). It’s a classical, phenomenological way of thinking – once you change the movement of a body, all of a sudden all layers of space (sensual, psychological, social, political, etc.) change too. So, it is a way of looking at a choreography of a human body in an amusement ride, and looking how these aesthetics could be developed a little bit more sensitively and conceptually. The key issue that I am working on is that throughout all the history of amusement parks it has been developed around the dimension of macho. Amusement rides become faster, taller, more intense and so on. We are living in a very interesting age, but we have come to this point where there are no actual possibilities to upgrade them more, because the peak of stimulation of a human body has already been reached.

Julijonas Urbonas. Euthanasia Coaster, 2010

Is it the reason that virtual amusements are rapidly developing nowadays?

In a way – yes. But you could also say that virtuality is taking over all kinds of real experiences. But if we speak about the end of real amusement parks, it is important to know that the piece I show in RIBOCA1, Euthanasia Coaster, is a celebration of that moment. It puts an end to progress that is directed towards extreme experiences. So this rollercoaster is made as an ultimate amusement ride that leaves no room for innovation, because you can’t go any further. In a way, it’s kind of like a celebration or a monument for the dying amusement ride.

In one way or another, the whole background of the creative process I do circles around these topics of what is moved in space and how the movement of a human body is changing all the layers of space.

Do you think that you have found the right balance between art, design and engineering?

I am not sure what could be seen as right or not. For me it all happens naturally. I quit my amusement park career (I was running the park myself for three years) and basically it was because I quickly became bored of one kind of a creative practice. Jumping from one field to another allowed me to combine different kinds of means of expression. On the other hand, I am interested in going beyond conventional tools of creativity, for example, applying the methods of sci-fi to amusement ride engineering and vice versa.

You mentioned that you were the director of the amusement park in Klaipēda. How did you decide to do that and – most importantly – how would you describe your experience as an administrator of an institution?

I was very young back then, about 23 years old. In reality, the park was owned by the municipality and they had a competition for the position of director. At that time, I was working on my Masters thesis which was a research on the future of amusement parks. I guess that really helped me to get the position, as well as my experience working with my father. And once I became the director, I began feeling this kind of an apocalyptical mood - during the Soviet times we had just a few forms of entertainment, that were mostly centralized, so when I became the director, nobody was stimulated by an amusement park. And then, once we became independent from the Soviet Union, new forms of entertainment were introduced.

So you felt like it was your duty to begin by creating a whole new idea of an amusement park?

Well it’s business, you need to create the numbers. First of all, we redecorated it to cover up all the Soviet traces. It didn’t work out that well so I decided to make it mobile. The whole Soviet Union was filled with the same packages of amusement parks because everything was centralized, starting from shoes to architecture. I wanted the amusement park to travel around Lithuania, be available for everyone. But the most interesting part for me was feeling the political material in the amusement park itself once we began redesigning and reengineering the whole thing. For example, all the Soviet rides were so excessively over-designed that some of them were almost impossible to make mobile. At a closer inspection, they looked more like military devices or monuments. The third challenge, that is still haunting me, was to re-choreograph the park. For example, you would see a centrifuge-led ride that usually spun very fast, but I wanted it to be extremely slow. Everybody would be so confused. (laughs) But also, by knowing specific changes in spinning, I wanted to make the rides so that they would induce vomiting.

It sounds exciting, but I still have to ask – why are you interested in this?

It is like choreography, yet your performers are the spectators themselves. It might sound superficial, but there is something much more complex going on. Something extremely ancient, instinctive, visceral, but also something very contemporary. First, you need to be aware that gravity has played such an extremely important role in the evolution of any living being that it is unimaginable we could have evolved the way we have without it. But all of sudden we are no longer constrained to the trajectory of falling from a tree or whatever. Once to be only-straight-down line of movement, today it could be turned into an aesthetic experience. Once a fatal fall from a cliff, today – an addictive, white-knuckle, whole body shaking and vomit-inducing roller coaster ride.

So, first you became interested in amusement parks and science, and then in art? Or vice versa?

I wouldn’t be able to tell which is which. Especially now.

You are not dividing those fields.

Certainly not. Sometimes I am more of an artist and sometimes my scientific research become artistic. Sometimes my artworks are exactly those research projects, only catapulted into a space which is open for wider interpretation – like gallery. Sort of artificially legitimising a lab object as an artwork. Of course, it doesn’t work for every object, but I really do believe that quite often art and science could be flipped and perceived as viable within their new respective frameworks.

Julijonas Urbonas. Oneiric Hotel capsules, 2013

I did a project, titled ‘’Oneiric Hotel’’ where I was researching all kinds of machines, tools and psychological techniques that are supposed to direct your dreams. I chose the most effective ones, and decided to make a hotel with these objects, where people can come, book a sleep session and try the equipment on themselves. Basically, the idea was to reconstruct these experiments that are usually done in scientific labs. In a way, it was just temporary relocation of lab object into public space, but a part of dreaming exhibitions, curated in the heads of the Hotel visitors.

But you can also never know what kind of people visit this Hotel. Their previous experiences and thoughts certainly affects their dreams.

That’s true – Oneiric Hotel had become a very intense project. It was really making an effect on people and that is why I quit doing that. During the first show, I noticed that one of the capsules didn’t work, because the equipment was wrongly wired. Nevertheless, people were telling stories whether it was working or not, so I realized that people actually were having a placebo effect. Since then I have started to pay very serious attention to every detail that had something to do with the atmosphere of the project. Starting from advertisement and the way people come to the Hotel, to reception desk, smell, sounds, etc. Everything that was a part of the placebo infrastructure. And during the course of the seventh session, it finally worked as I had intended all the time… It was set in a windowed gallery next to a food market and about half of the people who passed by, would also come in. It was so amazing! But the best thing was that even if someone couldn’t manage to sleep, taking into account the unusual environment, after a few days they would come back to me with wide open eyes, telling they had begun lucid dreaming.

How exactly does this system work?

If we refer to technological devices, then it’s quite simple. The hotel consists of two sets of the dream equipment: sleep monitoring system and stimulation devices. The sleeping visitors were monitored automatically and once the device detected the dreaming stage of their sleep it turned on the chosen stimulation device which either directs the content of the dream (mostly so-called gravitational dreams where you fly, levitate or do other gravitational activities) or triggers lucidity or both. All the devices are taken from scientific labs, but it’s always up to the audience to decide which one they want to try. The most effective ones were the, so called, inflatable slippers or pneumatic cups. You put them on your feet and once you’re dreaming they rhythmically squeeze. This device was found by accident, by Swedish Scientist Tore Nielson. He was researching thrombosis and circulation of blood in legs, but noticed that after these sessions people were reporting lucid dreams. In addition to the technologies, a very important part was mental preparation and the awareness of certain psychological techniques that I introduced myself before letting them fall asleep.

Julijonas Urbonas. Euthanasia Coaster on pedestal, 2010

Julijonas Urbonas. Euthanasia Coaster on pedestal, 2010

Could you explain the gravity principle that you refer to in your art?

All my projects have something to do with gravity. To unify them from the perspective of gravitational aesthetics, I am mostly interested in how you can push the definition and perception of the body, as well as the imagination to the extremes, by exposing them to altered states of gravity as an example of both bodily and imaginary extremism may be Euthanasia Coaster. Think of some fictional media, cinema or literature… it makes people emotionally and physically engaged with the narrative. For example, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, well-known for the woman’s murder episode. By the way, did you know that after the premier of the movie in the United States, the sales of shower curtains dropped rapidly? (Laughs) Anyway, I wanted to create something that goes beyond the conventional means of science fiction. Borrow something from sculpture and set-design, and create a unique kind of simulator that makes people almost feel the real ride. To kill people without killing.

And with Euthanasia Coaster you really succeeded?

You know, it has been 8 years since I created the object, but I still get a lot of e-mails every day, from people who want to try riding it, musicians who dedicate songs to the project, sci-fi writers who incorporate the idea into their novels. There are some people, who even blame me for spoiling the experience of amusement parks. With the Coaster, it feels like riding conceptually and physically at the same time, so I guess that I succeeded with this project.

Wait, you said that there really are people who want to try the ride?

Yes, I have quite the list of people who would like to be scientific objects if the project would advance towards realisation. Most of them are elderly from the US. But I don’t want to go this far. Actually there are no hints left whether it’s real or not. Once I talked to a pilot about Euthanasia Coaster and he said that he could hack my machine – he would wear an antigravity suit… but wait, do you know how people die on the coaster?

No, tell me.

Well first you are lifted up the rail to the top of 500 m and then dropped down, and there are seven vertical loops. When you enter the first loop, you are pushed against the seats so much that the blood goes down and there is none left at the upper part of the body. So, your brain starts to suffocate, it’s deprived of oxygen. And this is exactly what happens with pilots, who manoeuvre an aircraft. During these moments they wear specific suits, called G-trousers that infuse with hydraulic fluid, so it squeezes their legs and the blood comes back. And this pilot said that he would wear this suit and so he would survive my machine. And probably he would.

Julijonas Urbonas. Airtime, 2016

And what about gravitational aesthetics in other projects?

Two years ago I was selected to represent Lithuania in La Triennale di Milano. So I decided to make an empty space, just a blue-coloured floor, and name it Airtime. People would walk into the room, and while walking aroundthe space, the floor would slowly lift them up and drop back down, experiencing an episode of weightlessness. The main idea was to create a very simple movement of a group of people that would have no equivalents elsewhere. Directing unique physical circumstances that would generate unprecedented psychological conditions and social dynamics. Just think of this dropping floor – you could compare it with an airplane crash or collective suicides – everybody is synchronically falling and gasping for breath.

I’d rather associate it with a ride in an elevator.

Well, only if that elevator is broken and freefalls down. But in each case you are not ready for a bodily exploration of falling. What regards Airtime, you are not imprisoned as you would be in an amusement ride. You are fully present and it is up to you to decide what to do on the dropping floor. And what happens? People start consulting with each other about the best bodily positions to meet the drop, some start to grab each other, others get frightened and run away. Psychological confusion meets conceptual disorientation: is it art, an amusement ride, an elevator prototype?

Julijonas Urbonas. A Planet of People

Julijonas Urbonas. A Planet of People

Taking in account everything you’ve told me so far, it seems that you are kind of interested in the subject of death.

Not so much in the death itself, more in the extreme limits that life has. But actually some people call me Dr Death and one art critic even paraphrased it into Designer of Closed Eyes.

Actually, when I think about it, for some reason the new project that I’m working also has something to do with death. The project is called “A Planet of People”, an artistic and scientific feasibility study of creating an artificial cosmic body entirely from human bodies.

As Lithuania has a history of space exploration I thought it could be great to create its own planetary or extra-terrestrial identity that would have something to do with culture. Metaphorically speaking, our culture ends at the point where atmosphere starts. So, in my opinion, one of the possibilities for the far future is sending all human bodies to a specific location of space. Namely to one of the Lagrangrian points where there is no gravity. It’s an ideal place to preserve something, because space has vacuum and is very cold.It’s a cryogenic environment. When the body gets there it floats a little bit and then, after one or two weeks, it would start to attract other bodies and gather into a cluster. This project underlines the discussion of extra-terrestrial identity, as well as the question of a living being. We might think that everybody would be dead, but actually, once you look from the perspective of astrobiology, you have to radically rethink what we define as life.

This all is really confusing.

Yes, it is, because suddenly you’ve got to radically rethink everything that you know. The larger part of the human knowledge has been developed under the ecosystem and gravity of Earth. Therefore, once you cross Karman line, which defines the border between the earthly ecosystem and outer space, the conventional concepts of nature and life collapse. We have not to forget that such concepts are inseparable from culture and arts, hence we have astro-anthtropology and astro-arts that also strive at looking at these concepts from an extra-terrestrial perspective. This is where I became recently interested as well because it has something also to do with gravity and (extra-terrestrial) choreography.

You previously mentioned that choreography is a very important part of your projects. Do you consider every movement as some kind of a gravitational game?

In a way – yes. Actually, if you take the very definition of game and apply it to artworks, probably any artwork could become a game. In my case it’s more of a generative game. You create certain rules but you are not yet sure of how the game would manifest and materialize itself. And then something happens on its own. Think of certain experimental methods of material science. Sometimes it is just that specific environmental characteristics are being created and then certain materials are exposed to them. I am not that interested in the material itself, but more in the circumstances that turn one kind of material into another, or turn a roller coaster into Euthanasia Coaster.

Julijonas Urbonas. A Planet of People

Julijonas Urbonas. A Planet of People

In your opinion, what is complicated and what is complex art?

Complicated might be understood as something that is difficult to grasp or solve. Complex, for me, is a synonym of interdisciplinary and multi-layered. It is something that contains a lot of different interrelated layers that could not be conceived alone but within specific context or as the wholeness of complexity. For example, Euthanasia Coaster and Airttime might be seen complicated because it is difficult to assign them to an individual discipline. At the same time, they are complex because they are made possible due to a complex synthesis of diverse disciplines.

I think, nowadays art just becomes more complex for artists and complicated for the viewer.

Well I’m not sure, because you can just look at an artwork and appreciate it not as it is but as it could be.

Well, it certainly becomes more complicated for an art critic.

Yes, it’s probably the most complicated position! (laughs) When it comes to interpretations and reviews of art critics, quite often doesn’t make sense… because they use conventional tools of criticism. I think that the key problem of art criticism today, especially in the case of my work, is the lack of scientific, technological and craftsmanship knowledge.

But if we get back to the concept of merging art and science – do you think there are some aspects that could make one more important than the other? In context of Riga Biennial, for example.

If we talk from the perspective of RIBOCA1, or more specifically one of its venues, the Former Faculty of Biology of the University of Latvia, I think it nicely exemplifies the current situation of the dialogue between the arts and science. There are plenty art exhibitions and residencies in scientific venues but not vice versa. Art visits science, art is inspired by science, art borrows tools and methods from science. I think arts get more from science than science form arts. I wish there was a more mutually beneficial, sensitive, empathetic and tolerant dialogue.

Do you believe in tolerance as a concept?

I am interested in it, because to be tolerant means to be imaginative. In order to exist you have to believe in something that does not exist outside the realm of imagination. Such phenomena as morality, religion, culture, art, politics, economy, science are a human made fairy tale, developed to organize ourselves in complex societies. Once you realise it, you get totally lost, drown in nihilist thoughts. I think such a spirit defines zeitgeist. Once there is nothing to believe in, how do you live together and tolerate each other? You need to live in a sort of suspension of disbelief, a term referring to the wilful belief in the fake, for example, engaging oneself emotionally to a horror novel or a movie.