Katja Novitskova. Visual ecology

What can the ‘noble scavanger’ idea give us? A conversation with the Estonian artist whose works are currently on view at London’s Whitechapel Gallery.

09/08/2018

Katja Novitskova is regarded as one of Estonia’s most internationally renown artists. She developed her practice in Amsterdam and Berlin, and the locations of her current exhibitions are globe-spanning – Europe, Asia and the USA. Behind such sweeping success lies a person who, in addition to having a strong work ethic, has grasped critical thinking, can perceptively react to today’s cultural processes, has mastered interdisciplinary synthesis in the field of visual art, and continually works towards renewing an artistic system that gravitates towards universality. Novitskova is an artist who delicately and thrillingly plays with things and phenomena that form our reality on a universal level; she is interested in virtual reality, digital anthropology, reusing images, and visual ecology. Ultimately, the main vector in her development as an artist could be taken to be the timely and quite complex question: ‘How is it possible to be an artist in a world that is already oversaturated with images?’

Katja Novitskova. An installation from the series Macro Expansion. 2012

In addition to ongoing participation in international projects, over the last two years Novitskova has increasingly been working with art institutions in her native country. After further developing a project with which she had represented Estonia at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, in 2018 she exhibited it at a solo engagement at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn. Taking on a more chamber-like format, it evolved into the exhibition Invasion Curves, which premiered at one of London’s leading art institutions, the Whitechapel Gallery. On this show, which has become something of a summation of the expansive project, and on the formation and development of her visual style, I spoke with the Amsterdam- and Berlin-based Novitskova via Skype. In this case, a virtual and honest conversation between two persons appears to have been the most suitable format.

Let’s start at the very beginning. You studied semiotics at the University of Tartu, then graphic design at the Sandburg Instituut in Amsterdam. How did you come to study the visual arts?

I actually did also apply to the Estonian Academy of Arts, to the graphic design department; I wanted to study there from the beginning. I was interested in typography and calligraphy, and also webpage design. Design seemed more suitable and practical – it was important for me to study something with which I could make a living. But I didn’t get into the Academy, and so I signed up for semiotics at the University, together with my best friend from school. I tried again the following year, and I did get further along in the acceptance process, but I still didn’t make the final cut.

Then another friend from the Semiotics Department transferred to Tartu Art College. Inspired by her experience, in my third year of studies I also transferred to this school, to the department of Media Design, where Raivo Kelomees, Estonia’s pioneer in media and internet art, was a faculty member. That year was my favourite and most successful in terms of my personal self-realisation; it was also the period of my transitioning from semiotics to the visual arts. I was still interested in semiotics, but its focus on reading and writing long texts didn’t fit in with my focus on the theme of visuality –images and visual narratives. After I finished the semiotics programme, I was admitted to the master’s programme at the International School of New Media at the University of Lübeck in Germany. And from Germany I moved on to Amsterdam.

Katja Novitskova. A photo-sculpture in the exhibition Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015. MOMA, New York, 2015-2016

In Amsterdam you studied for a master’s in graphic design at the Sandburg Insituut. But when did you start taking part in exhibitions?

I went to Amsterdam to work on a project at the Mediamatic project space, and after that they offered me to stay on part-time. At that time I no longer wanted to study in Germany, and a small yet steady income in a creative field seemed like a ticket to the future. At Mediamatic, people work with new and experimental mediums; working there as a combination design assistant and producer was my first job experience with exhibitions. Then I signed up to the graphic design department at the Sandburg Instituut. It wasn’t as practically oriented, and was more experimental and philosophical, and allowed one to work with things that were closer to art than to design.

While studying there, I made a lot of artist friends and began to take part in modestly sized collective projects. At first I made flyers, but then I began to work on art on the internet – small webpages as a simple network form of art. My artist friends thought that they were interesting, and they started asking me to exhibit my work. However, I still couldn’t comprehend this world fully – at what moment does a webpage become art? Since many of my friends lived between Berlin and Amsterdam, I often went to Berlin, where there were galleries and museums, and instead of experimental web art, there were new-media exhibitions. That helped me to understand that world.

You’ve been named as one of the founders of post-internet art – one of the new movements in global contemporary art. How did that begin?

That’s nothing new; ten years have already passed, and I’m not the founder! I’ve spoken so much about it that I’d rather talk about something else. The concept itself comes from the title of a blog written by a writer that I know in New York – he was trying to describe and explain the new art that we were seeing around us and that we were creating; this reference aided me in labeling the field of meaning in which I was working. It’s lost all meaning now since the cycle has come to a close – the phenomena has become global and has lost its focus. In today’s art schools they’re already treating it like the past, as if it were history. I belong to the generation that, between 2008 and 2009, decided that today’s cultural elements can be used in art, and that art is unimaginable without smartphones and social networks. The question was – What does that mean for art? – and that is what I and many others attempted to answer.

Katja Novitskova. The exhibition If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes. The Estonian pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale. Photo: Luca Giardini

Yet it was you who published a book on this issue.

That was my master’s thesis at the Sandburg Instituut. My objective was, on the one hand, to publish a book since my specialty was graphic design, but on the other hand, to put together a collection of work by people who interested me. The book features approximately 50 different artists; it’s not my book but rather a compendium in which I assembled all of the knots of our creative web scattered throughout Berlin, Amsterdam, New York, etc., and presented them through the thematic prism of ecology and survival. The goal was to bring together a group of like-minded people with whom I could work after finishing my studies. I was terrified of the prospect of graduating with my master’s and then being ejected to the outside; I also didn’t want to fall out of this specific, global community of artists.

But now you look upon it as a finished cycle?

Yes, and I’m happy about it being done; I’d like to get rid of this stereotype in the perception of my work. Especially because I started working on something completely different in 2011. Once the new phenomenon has entered the common space, the common way of thought, there’s no point in basing anything upon it. It’s hard to find an artist of today who doesn’t have to deal with this issue in some way or another – the creative work of painters is even based upon new technologies, to a certain point.

Katja Novitskova. The exhibition If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes. Stage 2. Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, 2018. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

That’s a big issue in contemporary art – how many new characters and images can we create without consciously or unconsciously borrowing from something else. And is this even possible, since so much has already been said and there surely will be something similar somewhere else. One artist may consciously clean their visual space by working with the new minimalism, while another one, like you, may use images taken from the internet. Yet the latter is not sporadic copying/using, but assembling with a specific goal in mind through the use of, as the curator Kati Ilves calls it, a filter. You’re not creating something new as much as you are giving a new meaning to something that already exists – it’s a particular kind of ecology in terms of aesthetics, information, and even materials, since you frequently use already finished elements and mechanisms.

Yes; one could say it’s the idea of the noble scavenger.

A cultural janitor?

Well, yes. You find the shreds of civilisation and build your nests from them. I came to art from design, where the organisation of information comes first, not self-expression. I’ve always liked to draw, but once I was an adult, I began to look for the answer to the question of: What is art in a world where there are more images than there are grains of sand in the desert – more than there are people to view them. On one hand, images lose their value, and a new level of image ecology appears: there are so many of them that they cease to exist separately; they become a kind of layer – like clothing on the body of civilisation. On the other hand, the democracy of art interests me: to create, all I need is a computer. It was these two ideas that led me to working with images, texts and so on, which are easy to find online.

My first works were based on the principle that it doesn’t have to all become a hard-to-digest ocean of images and information, but they do have to isolate specific signals, thereby building a kind of story, thought or feeling. To isolate and strengthen images that everyone has seen and recognises. At first this worked, but now the focus of my work has moved regardless of the fact that I use similar methods. The narrative that I wish to tell has become more complex and less elegant – not as naive, but it is a better representation of today’s world.

It’s become more layered.

Yes, and probably less likable as well.

From laconic meanings that concentrate on lovable characters, you’ve now arrived to a total space that is complex both technically and in terms of its level of informational capacity. Did that happen consciously, or what it, in a sense, inevitable, that is, the total installation as a complex yet tested method by which to incorporate the viewer into the artwork – to lure them into this special world in which they then have to get their bearings, observe and think, all on their own?

Already with my first photo-sculptures – very simple but effective ones – I was, firstly, interested in the viewer’s reaction, one that powerfully reacts to poignant images of animals. These sculptures were always exhibited in simple white spaces with good lighting: the experiment was to see if the viewer would immediately and instinctively take a picture of the sculpture and post it on social media. Once I understood that it worked, it was no longer interesting for me to repeat the same trick again and again. I was much more interested in the multilayered aspect and ecology of the images and the materials: lighting, podiums, etc.

It all happened gradually; new ideas and materials appeared from one exhibition to the next. I began to make small sculptures from plastic and polyurethane, and I discovered that in the dark and with the right lighting, this plastic looks very beautiful. I began to develop this moment, as well as my old desire to include something mechanical and with motion. The mechanical element came into being with the robot-like electric cradles; this idea came to full fruition in the project shown at the 57th Venice Biennale’s Estonian pavilion, the Kumu Museum, and Whitechapel Gallery in London. I think that its execution at the Kumu exhibition was better than the one in Venice, but at Whitechapel I had already introduced new elements.

Now, instead of one sculpture that captivates the viewer and entices them to take pictures of it, the whole space and the web of connections, meanings and forms becomes the work of art. I try to create something that cannot be experienced anywhere else except in this exhibition. Here the result is different than with my earlier works: even if the viewers take pictures of it, they will be unable to capture the dynamic total. At the same time, I’m interested in the possibility of returning to the beginning – the making of a sculpture that will look good in a regular environment. A total exhibition requires a great amount of energy and funding, but it’s important to me whether it’s being made for a specially equipped museum, or if it’s going to be an object that can sit in someone’s house and still be regarded as art.

.jpg)

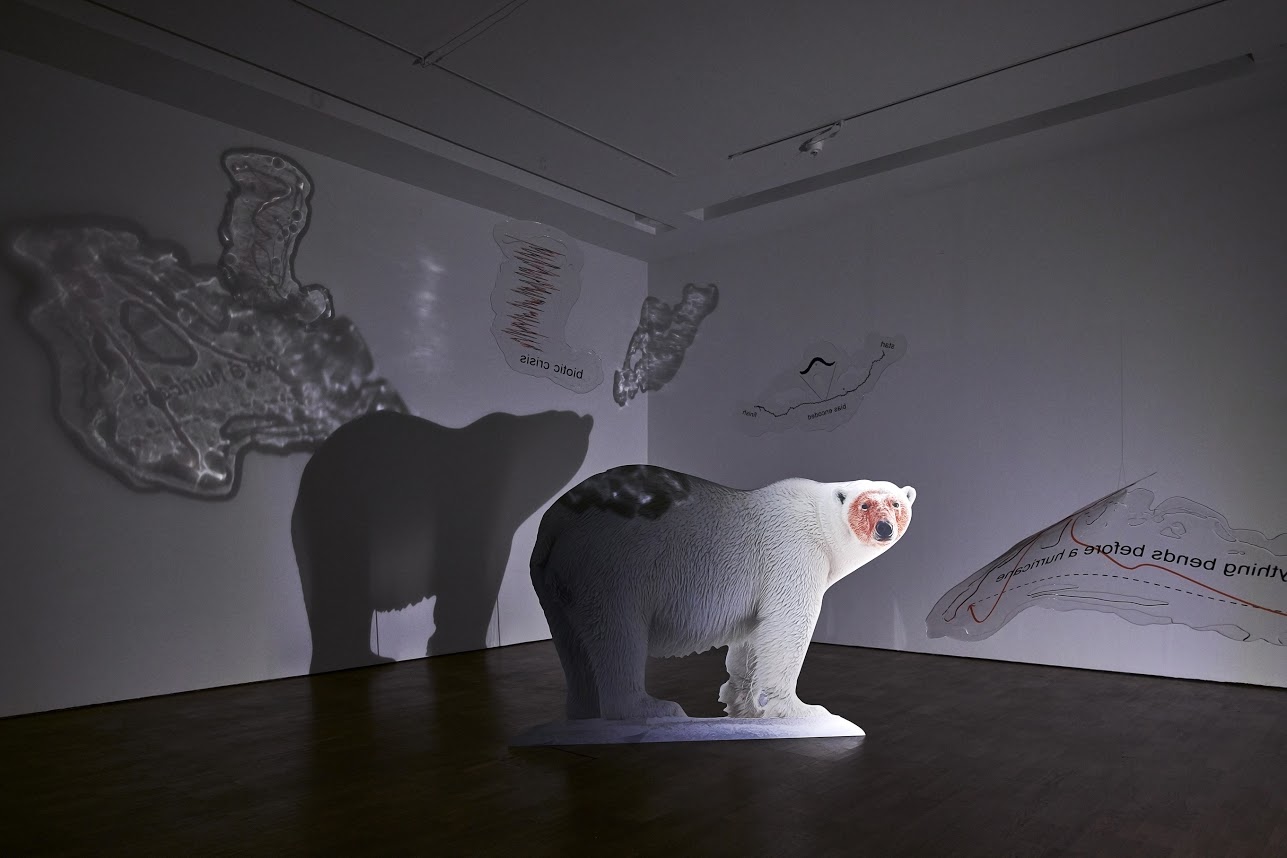

Katja Novitskova. The exhibition Invasion Curves. Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2018. Photo: Andrew Redford

Your works look as if a whole lab had worked on them, but it’s actually just you and your computer.

I create all of the computer files myself. The photo-sculptures are made in cooperation with a company in Berlin; they know what I need: I send them the files and they send me the sculpture. Over the years we’ve perfected both the sculpture constructions and those of the pedestals. All of the electric sculptures or objects from polyurethane I make in the studio by myself, with only the aid of a temporary assistant. In complex situations, I sometimes turn to certain companies in Berlin that specialise in art objects. But most of the work is done by me alone; that way I can control the process with my computer, even if I’m travelling.

Your oeuvre could be called a visual essay. It’s based on visual images, but at the same time, it’s a discussion, an invitation to reflection that works on a variety of levels. When looking at your exhibitions, one can gain a total emotional experience rather quickly, but one can also study every symbol and think about the issues addressed, either right there or later, because these questions remain with the viewer even after they have left.

I think that if I were able to give the viewers the whole context behind every work telepathically, they would like them even more. Perhaps not in a textual format, but I’d like for this information to be more accessible: for instance, what sort of worms are these and why are they here. Unfortunately, I don’t have the time to write all of that down and formulate it. That’s why I try to participate in the writing of the texts that accompany my exhibitions, so that I can include important key words. I would like for everybody to be aware of everything, but I have to become used to the fact that every viewer comes to the work with their own baggage. I try to make the kind of works through which even a person not versed in its background can gain a transformative experience.

I think that your works can be read even with a minimal knowledge of their underlying context. Moreover, your technique of enlarging the small (worms, molecules) or minimising the large (a map of constellations), despite their fragmentation, pulls one into a unifying and universal feeling of a micro- or macro-universe. What is interesting is that your works are a critique of the technological world done with tools that come from this same world. The images of the natural world in your works are shown not with the eye of a conscious photographer, but as data captured by a (semi-)automatic camera.

At first I used for my sculptures photographs that had been taken by people, but at the Kumu exhibition there was just one image like this – the polar bear. These photographs are a vivid example of image politics: exploiting nature both materially and virtually, people chase after animals and take pictures that become a product of attention politics. That’s why I decided to increasingly use images from automatic and laboratory sources which don’t have the romanticism of wild nature. It believe that that’s a much more realistic and critical approach.

Katja Novitskova. The exhibition If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes. Stage 2. Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, 2018. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Tell me about your latest exhibition. I understand that the project on view at Whitechapel Gallery is a further development of the material that was exhibited at Kumu, but with new elements.

I didn’t have the chance to make new works for Whitechapel Gallery, so I based it on the Kumu project. Since this space is much smaller than the one at Kumu, I had to make a succinct selection and I stayed with these elements: the electric cradles, two installations with photo-sculptures, hanging elements made of polyurethane, and an assemblage of clay tablets. I changed the video part that the electric cradles ‘watch’. The presentation at Kumu with the changing images didn’t work at Whitechapel Gallery, so I switched it out with a video featuring the image of a rotating human brain. That one looked better there, and so all of the videos were projected onto bubble-wrap instead of walls. We decided to build an architectural structure that isolated the installation and created the feeling of a modern laboratory which has been halfway destroyed.

The idea of the laboratory connects to the idea of a membrane between the inner and outer worlds: the bubble-wrap became both a projection screen and a metaphor for a shell that unites all of the elements of the installations into a single whole. The execution was economic in terms of its budget, but the bubble-wrap screen did indeed look like pixels were making up the structure of an image, giving it a feeling of virtual-reality and dimension. As a result, I understood that if I have a new exhibition with a good budget, one in which I continue to work with totality, then I’d like to increase the cooperation with an architect so as to take this totality towards an architectural structure. Architectural elements help create an atmosphere – the exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery looks like the set for a science-fiction film even more than the one at Kumu. Yet, naturally, there arises the question of – do I want my exhibition to be perceived as an amusement park: these are boundaries that I wouldn’t want to overstep. I want my exhibitions to be intellectual, not reminiscent of Disneyland.

Katja Novitskova. The exhibition Invasion Curves. Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2018. Photo: Andrew Redford

Here arises the issue of how to balance between total reality and the so-called hyper-reality, which Umberto Eco criticised.

What I like about art, and which you won’t find in the world of commerce, is the state of being halfway finished. There is a peculiar kind of truth in these cheap materials and small budgets. However, if you begin to create a hyper-realistic attraction from them, you lose the gentle state of art being ‘halfway finished’. That’s why I don’t work with real robots but with imitations: there’s something simple there, even primitive, yet it is real.

Nevertheless, art is based on conditionality. No matter how total it may be, it doesn’t hide the status of its other reality: that which is left unsaid – the ephemeral. Whereas Disneyland tries to replace reality by creating a simulacrum in which recreation dominates.

Yes; it’s a reality that has been created in order to manipulate emotions very precisely.

Even in cases where artists work with high-quality installations and teams of assistants, there sometimes arises an industrial aftertaste. It’s a pity that so much energy goes towards building instead of creating.

Yes, this is a danger that one must try to avoid so as not to be pulled into this black hole of manufacturing.

What else, besides scientific studies and the world of technology, inspires you? How about modern-day culture – films, books, science-fiction? Is that all just background noise, or is it a direct source of ideas? The titles of two of your recent exhibitions come from Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner.

I don’t like Ridley Scott as a film director, but I use his films as cultural context. I don’t read science-fiction; I basically read articles and books that deal with the scientific process, in the fields of philosophy, ecology or technology. That’s how I came upon the research study of a Princeton University sociologist on the relationship between humans and robots in the context of interplanetary exploration; that inspired me. I also read philosophical texts that I can somehow incorporate into my works. So, yes – it is the source of inspiration for my works. For me personally, music is much more important. I’ve grown up listening to electronic music – it is an antidepressant, a way to connect with people, and a way to culturally enrich oneself.

Katja Novitskova. The exhibition Invasion Curves. Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2018. Photo: Andrew Redford

Do you use music in your works, or are those two worlds that you don’t want to bring together?

In the Whitechapel project dealing with the theme of totality, I worked with my partner: he’s a musician and he created a soundtrack specially for the exhibition. I think that I’ll use more music in the future – perhaps not even just in the background, but as a much more active part of the exhibition; just like I use lights and movements now, I could introduce some musical interventions.

What are your upcoming plans and exhibitions?

In the autumn I’m going to participate in several group shows; I’m not planning a new solo show. The exhibition at Whitechapel closed the Venice-Tallinn-London cycle, and now I’d like to create a new group of works. Starting a new stage of work with new research and at a new level – perhaps not right away. This is the first time in many years that I’ve had the chance to deal with everyday, practical things.

You’ve participated in exhibitions in Europe, Asia and the USA. From the sidelines, it seems like a normal pace and scale of mobility for an artist these days. Yet there must be a huge amount of work behind all of it.

Yes, it means a lot of work, and the main driving force behind it is my fear – the fear of no longer being in the midst of things, the fear that all of these projects will soon end. I realise that I will not be able to sustain this level of activity forever; at some point I will have to give more attention to, for instance, family, friends or my health. That’s exactly why I’ve spent the last few years working very intensively, creating a base for what I hope will be a more calm period of creativity. My dream is to continue being an artist into my old age; I don’t want to do anything else.

With such a background of international success and mobility, how do you relate to your roots? I’ve read other interviews with you in which you stress that you have a hybrid identity, and that the universal aspect of themes and the language of art are more important to you than, say, the issue of nationality.

It’s simply that when you have only one life, and you want to work with something that is very important to you, you understand that the question of nationality is secondary. In daily life it is very important, of course, but in my creative work I try to work on, you could say, a cosmic level. I don’t disregard problems dealing with national politics, and not only in terms of Estonia; there’s a lot that I don’t accept from a civic standpoint. Although I was born in Estonia, I grew up in a Russian bubble – I don’t have any Estonian relatives, and some of my relatives still can’t get Estonian citizenship. However, my first attempts at attaining universality took place in Estonia, and now I have a lot of good Estonian friends. When I was in high school I discovered Estonian music shows and concerts that influenced me greatly at the time, and since then, it has happened in all other spheres: if you and another person are linked by something that is somehow related to art (in the broadest of senses), then that is the most important thing. I try to orient myself on a vector that connects me to a person regardless of their nationality.

Katja Novitskova’s sculptures Cuttlefish Love and Earth (in the back). From the project Earth Potential, 2017, City Hall Park, New York. Photo: Liza Laigona